Kendal College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Employer Satisfaction League Table

COLLEGE EMPLOYER SATISFACTION LEAGUE TABLE The figures on this table are taken from the FE Choices employer satisfaction survey taken between 2016 and 2017, published on October 13. The government says “the scores calculated for each college or training organisation enable comparisons about their performance to be made against other colleges and training organisations of the same organisation type”. Link to source data: http://bit.ly/2grX8hA * There was not enough data to award a score Employer Employer Satisfaction Employer Satisfaction COLLEGE Satisfaction COLLEGE COLLEGE responses % responses % responses % CITY COLLEGE PLYMOUTH 196 99.5SUSSEX DOWNS COLLEGE 79 88.5 SANDWELL COLLEGE 15678.5 BOLTON COLLEGE 165 99.4NEWHAM COLLEGE 16088.4BRIDGWATER COLLEGE 20678.4 EAST SURREY COLLEGE 123 99.2SALFORD CITY COLLEGE6888.2WAKEFIELD COLLEGE 78 78.4 GLOUCESTERSHIRE COLLEGE 205 99.0CITY COLLEGE BRIGHTON AND HOVE 15088.0CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COLLEGE6178.3 NORTHBROOK COLLEGE SUSSEX 176 98.9NORTHAMPTON COLLEGE 17287.8HEREFORDSHIRE AND LUDLOW COLLEGE112 77.8 ABINGDON AND WITNEY COLLEGE 147 98.6RICHMOND UPON THAMES COLLEGE5087.8LINCOLN COLLEGE211 77.7 EXETER COLLEGE 201 98.5CHESTERFIELD COLLEGE 20687.7WEST NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COLLEGE242 77.4 SOUTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE AND STROUD COLLEGE 215 98.1ACCRINGTON AND ROSSENDALE COLLEGE 14987.6BOSTON COLLEGE 61 77.0 TYNE METROPOLITAN COLLEGE 144 97.9NEW COLLEGE DURHAM 22387.5BURY COLLEGE121 76.9 LAKES COLLEGE WEST CUMBRIA 172 97.7SUNDERLAND COLLEGE 11487.5STRATFORD-UPON-AVON COLLEGE5376.9 SWINDON COLLEGE 172 97.7SOUTH -

Outcomes from IQER: 2010-11 the Student Voice

Outcomes from IQER: 2010-11 The student voice July 2012 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................... 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................ 2 Student engagement: context ................................................................................................. 3 Themes .................................................................................................................................. 6 Theme 1: Student submissions for the IQER reviews ......................................................... 6 Theme 2: Student representation in college management: extent of student representation, specific student-focused committees and contact with senior staff ............. 7 Theme 3: How colleges gather and use student feedback information ................................ 8 The themes in context ............................................................................................................ 9 Conclusions .......................................................................................................................... 10 Areas of strength as indicated by the evidence from the reports ....................................... 10 Areas where further work is required ................................................................................ 11 Appendix A: Good practice relating to student engagement ................................................ -

Framework Users (Clients)

TC622 – NORTH WEST CONSTRUCTION HUB MEDIUM VALUE FRAMEWORK (2019 to 2023) Framework Users (Clients) Prospective Framework users are as follows: Local Authorities - Cheshire - Cheshire East Council - Cheshire West and Chester Council - Halton Borough Council - Warrington Borough Council; Cumbria - Allerdale Borough Council - Copeland Borough Council - Barrow in Furness Borough Council - Carlisle City Council - Cumbria County Council - Eden District Council - South Lakeland District Council; Greater Manchester - Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council - Bury Metropolitan Borough Council - Manchester City Council – Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council - Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council - Salford City Council – Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council - Trafford Metropolitan Borough - Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council; Lancashire - Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council – Blackpool Borough Council - Burnley Borough Council - Chorley Borough Council - Fylde Borough Council – Hyndburn Borough Council - Lancashire County Council - Lancaster City Council - Pendle Borough Council – Preston City Council - Ribble Valley Borough Council - Rossendale Borough Council - South Ribble Borough Council - West Lancashire Borough Council - Wyre Borough Council; Merseyside - Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council - Liverpool City Council - Sefton Council - St Helens Metropolitan Borough Council - Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council; Police Authorities - Cumbria Police Authority - Lancashire Police Authority - Merseyside -

North West Introduction the North West Has an Area of Around 14,100 Km2 and a Population of Almost 6.9 Million

North West Introduction The North West has an area of around 14,100 km2 and a population of almost 6.9 million. The metropolitan areas of Greater Manchester and Merseyside are the most significant centres of population; other major urban areas include Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 490 people per km2, making the North West the most densely populated region outside London. This population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region; Cumbria in the north has just 24 people per km2. The economy The economic output of the North West is almost £119 billion, which represents 13 per cent of the total UK gross value added (GVA), the third largest of the nine English regions. The region is very varied economically: most of its wealth is created in the heavily populated southern areas. The unemployment rate stood at 7.5 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2010, compared with the UK rate of 7.9 per cent. The North West made the highest contribution to the UK’s manufacturing industry GVA, 13 per cent of the total in 2008. It was responsible for 39 per cent of the UK’s GVA from the manufacture of coke, refined petroleum products and nuclear fuel, and 21 per cent of UK manufacture of chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres. It is also one of the main contributors to food products, beverages, tobacco and transport equipment manufacture. Gross disposable household income (GDHI) of North West residents was one of the lowest in the country, at £13,800 per head. -

Regional Profiles North-West 29 ● Cumbria Institute of the Arts Carlisle College__▲■✚ University of Northumbria at Newcastle (Carlisle Campus)

North-West Introduction The North-West has an area of around 14,000 km2 and a population of over 6.3 million. The metropolitan area of Greater Manchester is by far the most significant centre of population, with 2.5 million people in the city and its wider conurbation. Other major urban areas are Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 477 people per km2, making the North-West the most densely populated region outside London. However, the population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region. Cumbria, by contrast, has the third lowest population density of any English county. Economic development The economic output of the North-West is around £78 billion, which is 10 per cent of the total UK GDP. The region is very varied economically, with most of its wealth created in the heavily populated southern areas. Important manufacturing sectors for employment and wealth creation are chemicals, textiles and vehicle engineering. Unemployment in the region is 5.9 per cent, compared with the UK average of 5.4 per cent. There is considerable divergence in economic prosperity within the region. Cheshire has an above average GDP, while Merseyside ranks as one of the poorest areas in the UK. The total income of higher education institutions in the region is around £1,400 million per year. Higher education provision There are 15 higher education institutions in the North-West: eight universities and seven higher education colleges. An additional 42 further education colleges provide higher education courses. There are almost 177,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) students in higher education in the region. -

PROSPECTUS Full-Time Courses & Apprenticeships 2019 - 2020

PROSPECTUS Full-Time Courses & Apprenticeships 2019 - 2020 www.kendal.ac.uk T: 01539 814700 E: [email protected] @kendalcollege Contents Welcome to STUDYING AT KENDAL COLLEGE Welcome to Kendal College ........................... 3 Kendal College Creating Bright Futures ........................................ 4 What our former students say ....................... 5 State-of-the-Art Facilities .......................................6-7 I am delighted that you are thinking about coming to Kendal College Dedicated Study Spaces & for the next phase of your education. Progression Centre .................................................. 8 Student Life ................................................................... 9 We are a modern and forward-thinking Our superb facilities are matched by our Opportunities to Consider ...........................10-11 college offering a variety of qualifications, team of staff. You will be taught by experts Understanding Levels ...........................................12 and just by considering Kendal College as a who are highly qualified, professional and Careers Advice ..........................................................13 place to study you have already taken the friendly, and are passionate about their Visit Us .............................................................................14 first step towards a bright future. We have subject and teaching. Applying to College ..............................................15 a lot to offer, so I am sure you will find a Kendal College is a fantastic -

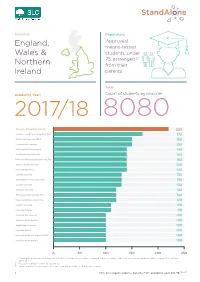

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Teacher Regional Improvement Project (TRIP) Summaries - Round 1

Teacher Regional Improvement Project (TRIP) summaries - round 1 Lead Delivery Partner is indicated in bold type. Knowledge Hub: North (12 projects) 1. Blackpool and The Fylde College, Nelson and Colne College, The Lancashire LEP, Wakefield College, Bolton College, Hopwood Hall College The aim of the project is to undertake research to inform the development of long term CPD to support teaching staff who are in line to deliver the first T Level in Construction (Design, Surveying and Planning), with a specific focus on emerging technologies. 2. Bolton College, Blackburn College, Greater Manchester Combined Authority, Hopwood Hall College, The City of Liverpool College, Oldham College, Priestly College, Wirral Metropolitan College The project aims to test effective strategies for the development of industry-level knowledge and skills required by teachers delivering the T Levels in Digital. The project will seek to identify effective methods for embedding employer support to help bridge the gap between industry needs and teaching knowledge and experience, for the delivery of the three Digital T Level pathways. 3. Burnley College, Blackburn College, Priestley College, Myerscough College, Bolton College, Southport College, STEMFirst, Develop EBP The project aims to analyse the impact of industry placements on the teaching and learning cycle to enable partners to support both learners and employers before, during and following an industry placement as well as aligning classroom delivery to the placement objectives. 4. Gateshead College, Stockton Riverside College, Derwentside College, Lakes College The project aims to develop teaching practice in innovative assessment methods in Early Years and Childcare which will allow students to generate evidence of their core skills and to ensure that assessment methods are in line with industry needs. -

Web and Video Conferencing Trends in Education 2017

Survey Partners Web & Video Conferencing Trends in Education Survey Report 2017 Contents The Survey 3 Survey Methodology and Respondents’ Profile 5 Key Findings 6 Conclusion 11 Appendix 1: Full Survey Questions 12 Appendix 2: Participating Organisations 19 Acknowledgements The survey team at iGov Survey would like to take this opportunity to thank all of those who were kind enough to take part – and especially to those who found the time to offer additional insights through their extra comments. We would also like to thank our partner, Brother UK, for their assistance in compiling the survey questions, scrutinising the responses and analysing the results. Web & Video Conferencing Trends in Education 2017 is © copyright unless explicitly stated otherwise. All rights, including those in copyright in the content of this publication, are owned by or controlled for these purposes by iGov Survey. Except as otherwise expressly permitted under copyright law or iGov Survey’s Terms of Use, the content of this publication may not be copied, produced, republished, downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way without first obtaining iGov Survey’s written permission, or that of the copyright owner. To contact the iGov Survey team: Email: [email protected] Tel: 0845 094 8567 Address: FAO Sandra Peet, Pacific House, Pacific Way, Digital Park, Salford Quays, M50 1DR Page 2! of 20! Web & Video Conferencing Trends in Education 2017 The Survey Traditional methods of teaching are fast becoming obsolete. Gone are the days of chalkboards and textbooks. The modern classroom must now cater to changing expectations, from staff, students and parents alike, as pupils prepare for the digital world of education and beyond. -

Proposal for Merger Between Carlisle College and Ncg Initial Outline Proposal

Carlisle college PROPOSAL FOR MERGER BETWEEN CARLISLE COLLEGE AND NCG INITIAL OUTLINE PROPOSAL GIVE US YOUR VIEWSPROPOSAL FOR MERGER BETWEEN e CARLISLE COLLEGE AND NCG INITIAL OUTLINE PROPOSAL Carlisle Carlisl college college 1 Proposal for merger between Carlisle College and NCG: Initial Outline Proposal Contents Page no 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Background 5 3. The Geographic Area Impacted by Merger 8 4. Carlisle College 14 5. NCG 17 6. Strategic Objectives for the Merged College 26 7. Brand and Quality Arrangements 33 8. Financial and Legal Update 35 9. Property and Estates Strategy 38 10. Governance Arrangements 41 11. People Arrangements 43 12. Consultation Process and Next Steps 45 Appendix 1 – NCG Structure Incorporating Carlisle College 46 Purpose Carlisle College and NCG propose to merge to form a single institution. This proposal document explains how the merger will take place, and how it will improve the future range and quality of training and education in Carlisle and Cumbria. Your views are sought on the merger as part of a transparent consultation process. 1 www.ncgrp.co.uk | www.carlisle.ac.uk 1. Executive Summary Carlisle College Carlisle College is a small general further Education College, serving the post 16 education and training needs of North Cumbria. The college campus, located in Carlisle, is the only GFE College within a 35 mile radius of Carlisle. It has cross- border arrangements with Scotland for learners living within the travel to learn area. To this end it provides a broad range of learning programmes delivered in a variety of ways. The college offers mainly vocational programmes on a full-time, part-time and evening basis. -

The Education (Further Education Corporations) Order 1992

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1992 No. 2097 EDUCATION, ENGLAND AND WALES The Education (Further Education Corporations) Order 1992 Made - - - - 3rd September 1992 Laid before Parliament 4th September 1992 Coming into force - - 28th September 1992 In exercise of the powers conferred on the Secretary of State by sections 15 and 17(2)(a) of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992(1) the Secretary of State for Education, as respects England, and the Secretary of State for Wales, as respects Wales, hereby make the following Order: 1. This Order may be cited as the Education (Further Education Corporations) Order 1992 and shall come into force on 28th September 1992. 2. The educational institutions maintained by local education authorities and the county and controlled schools specified in the Schedule to this Order appear to the Secretary of State to fall within subsections (2) and (3) respectively of section 15 of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992. 3. The “operative date” in relation to further education corporations established under section 15 of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992 and to the institutions which they conduct shall be 1st April 1993. John Patten 3rd September 1992 Secretary of State for Education David Hunt 3rd September 1992 Secretary of State for Wales (1) 1992 c. 13. Document Generated: 2015-10-29 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. -

237 Colleges in England.Pdf (PDF,196.15

This is a list of the formal names of the Corporations which operate as colleges in England, as at 3 February 2021 Some Corporations might be referred to colloquially under an abbreviated form of the below College Type Region LEA Abingdon and Witney College GFEC SE Oxfordshire Activate Learning GFEC SE Oxfordshire / Bracknell Forest / Surrey Ada, National College for Digital Skills GFEC GL Aquinas College SFC NW Stockport Askham Bryan College AHC YH York Barking and Dagenham College GFEC GL Barking and Dagenham Barnet and Southgate College GFEC GL Barnet / Enfield Barnsley College GFEC YH Barnsley Barton Peveril College SFC SE Hampshire Basingstoke College of Technology GFEC SE Hampshire Bath College GFEC SW Bath and North East Somerset Berkshire College of Agriculture AHC SE Windsor and Maidenhead Bexhill College SFC SE East Sussex Birmingham Metropolitan College GFEC WM Birmingham Bishop Auckland College GFEC NE Durham Bishop Burton College AHC YH East Riding of Yorkshire Blackburn College GFEC NW Blackburn with Darwen Blackpool and The Fylde College GFEC NW Blackpool Blackpool Sixth Form College SFC NW Blackpool Bolton College FE NW Bolton Bolton Sixth Form College SFC NW Bolton Boston College GFEC EM Lincolnshire Bournemouth & Poole College GFEC SW Poole Bradford College GFEC YH Bradford Bridgwater and Taunton College GFEC SW Somerset Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College SFC SE Brighton and Hove Brockenhurst College GFEC SE Hampshire Brooklands College GFEC SE Surrey Buckinghamshire College Group GFEC SE Buckinghamshire Burnley College GFEC NW Lancashire Burton and South Derbyshire College GFEC WM Staffordshire Bury College GFEC NW Bury Calderdale College GFEC YH Calderdale Cambridge Regional College GFEC E Cambridgeshire Capel Manor College AHC GL Enfield Capital City College Group (CCCG) GFEC GL Westminster / Islington / Haringey Cardinal Newman College SFC NW Lancashire Carmel College SFC NW St.