Rheumatic Heart Disease Patients' Adherence to Secondary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administrative Region, Zone and Woreda Map of Oromia a M Tigray a Afar M H U Amhara a Uz N M

35°0'0"E 40°0'0"E Administrative Region, Zone and Woreda Map of Oromia A m Tigray A Afar m h u Amhara a uz N m Dera u N u u G " / m r B u l t Dire Dawa " r a e 0 g G n Hareri 0 ' r u u Addis Ababa ' n i H a 0 Gambela m s Somali 0 ° b a K Oromia Ü a I ° o A Hidabu 0 u Wara o r a n SNNPR 0 h a b s o a 1 u r Abote r z 1 d Jarte a Jarso a b s a b i m J i i L i b K Jardega e r L S u G i g n o G A a e m e r b r a u / K e t m uyu D b e n i u l u o Abay B M G i Ginde e a r n L e o e D l o Chomen e M K Beret a a Abe r s Chinaksen B H e t h Yaya Abichuna Gne'a r a c Nejo Dongoro t u Kombolcha a o Gulele R W Gudetu Kondole b Jimma Genete ru J u Adda a a Boji Dirmeji a d o Jida Goro Gutu i Jarso t Gu J o Kembibit b a g B d e Berga l Kersa Bila Seyo e i l t S d D e a i l u u r b Gursum G i e M Haro Maya B b u B o Boji Chekorsa a l d Lalo Asabi g Jimma Rare Mida M Aleltu a D G e e i o u e u Kurfa Chele t r i r Mieso m s Kegn r Gobu Seyo Ifata A f o F a S Ayira Guliso e Tulo b u S e G j a e i S n Gawo Kebe h i a r a Bako F o d G a l e i r y E l i Ambo i Chiro Zuria r Wayu e e e i l d Gaji Tibe d lm a a s Diga e Toke n Jimma Horo Zuria s e Dale Wabera n a w Tuka B Haru h e N Gimbichu t Kutaye e Yubdo W B Chwaka C a Goba Koricha a Leka a Gidami Boneya Boshe D M A Dale Sadi l Gemechis J I e Sayo Nole Dulecha lu k Nole Kaba i Tikur Alem o l D Lalo Kile Wama Hagalo o b r Yama Logi Welel Akaki a a a Enchini i Dawo ' b Meko n Gena e U Anchar a Midega Tola h a G Dabo a t t M Babile o Jimma Nunu c W e H l d m i K S i s a Kersana o f Hana Arjo D n Becho A o t -

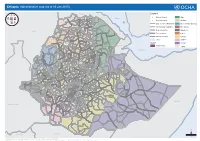

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (August 2017)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (August 2017) ERITREA National capital P Erob Tahtay Adiyabo Regional capital Gulomekeda Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Ahferom Red Sea Humera Adigrat ! ! Dalul ! Adwa Ganta Afeshum Aksum Saesie Tsaedaemba Shire Indasilase ! Zonal Capital ! North West TigrayTahtay KoraroTahtay Maychew Eastern Tigray Kafta Humera Laelay Maychew Werei Leke TIGRAY Asgede Tsimbila Central Tigray Hawzen Medebay Zana Koneba Naeder Adet Berahile Region boundary Atsbi Wenberta Western Tigray Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele Zone boundary Tanqua Abergele P Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Tsegede Tselemt Mekele Town Special Enderta Afdera Addi Arekay South East Ab Ala Tsegede Mirab Armacho Beyeda Woreda boundary Debark Erebti SUDAN Hintalo Wejirat Saharti Samre Tach Armacho Abergele Sanja ! Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Addis Ababa Ziquala Maychew ! Wegera Metema Lay Armacho Wag Himra Endamehoni Raya Azebo North Gondar Gonder ! Sekota Teru Afar Chilga Southern Tigray Gonder City Adm. Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Gaz Gibla Zone 4 (Fantana Rasu ) Elidar Amhara Gelegu Quara ! Takusa Ebenat Gulina Bugna Awra Libo Kemkem Kobo Gidan Lasta Benishangul Gumuz North Wello AFAR Alfa Zone 1(Awsi Rasu) Debre Tabor Ewa ! Fogera Farta Lay Gayint Semera Meket Guba Lafto DPubti DJIBOUTI Jawi South Gondar Dire Dawa Semen Achefer East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Delanta Habru Asayita P Tach Gayint ! Bahir Dar City Adm. Aysaita Guba AMHARA Dera Ambasel Debub Achefer Bahirdar Zuria Dawunt Worebabu Gambela Dangura West Esite Gulf of Aden Mecha Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Simada Thehulederie Kutaber Dangila Yilmana Densa Afambo Mekdela Tenta Awi Dessie Bati Hulet Ej Enese ! Hareri Sayint Dessie City Adm. -

Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Towards Rabies in Dedo District of Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia: a Community Based Cross-Sectional Study

Vol. 9(5), pp. 61-71, May 2017 DOI: 10.5897/IJMMS2017.1302 Article Number: 2DCB3CC64168 International Journal of Medicine ISSN 2006-9723 Copyright © 2017 and Medical Sciences Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJMMS Full Length Research Paper Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards rabies in Dedo district of Jimma zone, southwestern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study Nejash Abdela1*, Boru Midekso1, Jemal Jabir1 and Wezir Abdela2 1School of Veterinary Medicine, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Jimma University, P. O. Box. 307, Jimma, Ethiopia. 2School of Public Health, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia. Received 20 March, 2017: Accepted 19 April, 2017 Rabies is a fatal neglected viral zoonosis which causes encephalitis in many warm-blooded animals and humans. It is an incurable disease once the clinical signs appear. However, it can be prevented via vaccination and community awareness. This study was therefore designed to determine the level of community knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) regarding rabies. Cross sectional study was conducted from December 2016 to January 2017 in Dedo district, Jimma zone, southwestern Ethiopia. Multistage sampling technique was employed for selection of sample unit and data were collected from 135 household by face-to-face interview using a semi structured and validated questionnaire. Logistic regression was used for assessing the association of independent variable with KAP score. Out of 135 participants interviewed, 71.1% were urban and 57% were male respondents. All (100%) participants had heard about rabies and 88.9% were aware that rabies is zoonotic. -

Medicinal Plants Use and Conservation Practices in Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia

Vol. 7(3), pp. 202-210, March, 2015 DOI: 10.5897/IJBC2015.0822 Article Number: 65A316D51947 International Journal of Biodiversity ISSN 2141-243X Copyright © 2015 and Conservation Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJBC Full Length Research Paper Medicinal plants use and conservation practices in Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia Debela Hunde Feyssa, Chemeda Abdeta, Techale Berhan* and Manju Sharma College of Agriculture & Veterinary Medicine, Jimma University, Ethiopia. Received 2 February, 2015; Accepted 16 March, 2015 Traditional medicine has continued to be the most affordable and easily accessible source of treatment in the primary healthcare system of Ethiopia. However, the medicinal plants used for such treatments are becoming increasingly rare and vulnerable to extinction because of improper utilization and conservation practices. Hence, this paper was initiated with the aim to assess the use, management and conservation practices of medicinal plants in some selected districts of Jimma Zone, south west Ethiopia. Ethnobotanical methods such as focus group discussions, key informant interview, semistructured interview and field walks were used to collect ethnobotanical data on use and management practices of medicinal plants in the study area. Data collected were classified into the use of the plants and management practice. Data of the semistructured interview was analyzed using SPSS version 16 software. The result revealed that a total of 69 plant species were identified in the study area, of which 30 are nutraceuticals, 30 are collected at wild habitat and 39 are cultivated. Source of medicinal plants include: cultivation in home gardens, live fences, crop fields and wild collection from the nearby environment. -

Identification of Major Causes of Post-Harvest Losses Among

Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 3, Issue, 11, pp.040-043, November, 2011 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE IDENTIFICATION OF MAJOR CAUSES OF POSTHARVEST LOSSES AMONG SELECTED FRUITS IN JIMMA ZONE FOR PROFFERING VERITABLE SOLUTIONS *Adugna Debela, Gerba Daba, Diriba Bane and Kassaye Tolessa Jimma University College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Department of Horticulture and Plant Sciences, P. O. Box, 307, Jimma, Ethiopia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Horticultural crops are known for their high return per unit time and area. How ever, a significant Received 28th August, 2011 proportion of postharvest loss of these produces is experienced in Ethiopia. This postharvest loss Received in revised form contributes to the reduction of profit from the produce and leads to food insecurity. This survey 19th September, 2011 investigation and laboratory analysis was therefore conducted to study the causes and magnitude of Accepted 28th October, 2011 th post harvest loss of selected fruits in three different towns of Jimma Zone, South western Ethiopia Published online 20 November, 2011 from November 2010 to March 2011. The survey method was explored using carefully designed semi-structured questionnaire reflecting the proposed scope of study among producers, wholesalers Key words: and retailers of fruits in the fruit market chain. The chemical analysis was determined using the Banana, standard procedures in Postharvest laboratory of Jimma University College of Agriculture and Jimma, Veterinary Medicine. The result indicated that there were greater postharvest losses of mango Mango, (35.5%) and banana (40.0%) especially in Jimma town than in Agaro and Seka Chekorsa. -

Technical Efficiency of Smallholder Honey Farmers in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia 1

RUDN Journal of Economics 2020 Vol. 28 No. 1 7–22 http://journals.rudn.ru/economics Вестник РУДН. Серия: Экономика DOI 10.22363/2313-2329-2020-28-1-7-22 Research article UDC 332 Technical efficiency of smallholder honey farmers in Jimma zone, Ethiopia 1 Hailemariam Legesse1, Yadeta Bekele1, Mulubrihan Bayissa1, Tsega Lemma2 1Jimma University P.O. Box 307, Cluj-Napoca, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 2Stellenbosch University Private Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa Abstraсt. This study analyzes technical efficiency and determinants of the efficiency of honey production in the Gomma and Gera districts of the Jimma zone. The data were ob- tained from 194 randomly selected honey-producing smallholder farmers. A Cobb – Douglas stochastic frontier production analysis with the inefficiency effect model was used to estimate technical efficiency and identify the determinants of efficiency variations among honey farm- ers. The study showed that several hives and supplementary feeds positively and significantly influenced honey yield. This shows that there is room to increase honey productivity from the current level if farmers can efficiently use these input variables. The result further showed that there were differences in technical efficiency among honey producers in the study area. The discrepancy ratio, γ, which measures the relative deviation of output from the frontier level due to inefficiency, was about 84%. This implies that about 84% of the variation in ho- ney output among the farmers was attributed to technical inefficiency effects. The estimated mean level of technical efficiency of honey producers was about 74%. This reveals that there is a possibility to increase the level of honey output by about 26% through exploiting the exis- ting local practices and technical knowledge of the relatively efficient farmers. -

Full-Text (PDF)

Vol. 11(2), pp. 52-59, April-June 2020 DOI: 10.5897/IJLP2019.0658 Article Number: ECF35B363759 ISSN 2141-2448 Copyright © 2020 International Journal of Livestock Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJLP Production Full Length Research Paper Comparative test of the two final commercial dual-purpose breeds during early growth performance under on-farm management conditions in two districts of Jimma Zone, Ethiopia Belete Jorga1*, Wondmeneh Esatu2 ,Mohammed Ali3, Wasihun Hassen3, Ahmed Seid3, and Tekle Olbamo1 1Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Natural Resource, Jinka University, Ethiopia. 2Ethiopian Agricultural Research Institute, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia. 3Jimma University, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Department of Animal Science, Jimma, Ethiopia. Received 6 November, 2019; Accepted 17 January, 2020 This study was conducted to evaluate the production and reproduction performance of chicken breed under semi-scavenging system of Seka Chekorsa and Omo Nada districts of Jimma Zone. A total of 800 day old chicks were obtained from Debre Zeit Agricultural Research center. 50 day old chicks were distributed with hay box brooder, and the experiment was arranged in a nested design. The result of the current study indicated that male chickens of both breeds in this study reached sexual maturity and slaughter weight within four months in both districts and mature body weights of 1831.25 and 1569.18 g at Seka and 1615.00 and 1586.25g in Omo Nada, respectively for Lohmann dual and Dominant red barred. Although there was no statistically significant difference between the two breeds, Lohmann dual breeds attained age at first egg within 148 days and Dominant red barred (162.25 days) breeds in Seka Chekorsa and 157.50 and 160.25 days, respectively for lohmann and Dominant red barred in Omo Nada district. -

Prevalence and Socio-Demographic/Economic Risk

Open Access Library Journal Prevalence and Socio-Demographic/ Economic Risk Factors of Low and High Body Mass Index of Urban versus Rural Pregnant Women at Booking for Antenatal Care in Governmental Health Centers of Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia Chernet Hailu1*, Tariku Dejene2, Bosena Tebeje3 1Epidemiology Department, College of Public Health and Medical Sciences, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia 2College of Development Studies, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 3Nursing Department, College of Public Health and Medical Sciences, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia Email: *[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received 21 June 2015; accepted 5 July 2015; published 13 July 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Background: Low Body Mass Index (BMI) continues to be a major health burden in addition to the emergence of new competing public health priority (high BMI) in developing countries. Abnormal BMI threatens both the health and survival of mothers and their infants, because it increases their susceptibility to life-threatening problems during pregnancy, and during and following childbirth. Although a number of studies done on nutrition, none was done in pregnancy in our country in- cluding Jimma Zone. Objective: The aim of this study was to assess prevalence and identify the risk factors associated with BMI status of pregnant women of urban versus rural residents of Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 03 to Oc- tober 21, 2011 in randomly selected governmental health centers of Jimma Zone. -

Status of Honeybee Apismellifera Bandansii Pests and Pathogens in Seka Chokersa District of Jimma Zone, Ethiopia

International Journal of Research Studies in Biosciences (IJRSB) Volume 5, Issue 12, 2017, PP 12-27 ISSN No. (Online) 2349-0365 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0365.0512003 www.arcjournals.org Status of Honeybee Apismellifera Bandansii Pests and Pathogens in Seka Chokersa District of Jimma Zone, Ethiopia Desta Abi Gemedi Oromia Agricultural Research Institute (OARI), Adami Tulu Agricultural Research Center (ATARC), Oromia, Ethiopia *Corresponding Author: Desta Abi Gemedi, Oromia Agricultural Research Institute (OARI), Adami Tulu Agricultural Research Center (ATARC), Oromia, Ethiopia Abstract : A cross-sectional study was conducted in Seka Chokersa district, Ethiopia from November, 2015 to June, 2016 with overall objective of assessing honeybee pests, parasites and pathogens; associated risk factors; and estimating their potential effects on beekeeping. A cluster of 3 beekeeping rural kebeles were randomly taken to select 245 sample beekeepers for questionnaire survey. A total of 60 honeybee colonies were randomly sampled. Semi-structured questionnaire was developed, and pretested for assessing of beekeepers’ perception on honeybee pests, parasites, pathogens and associated predisposing conditions. Adult worker bees and bee brood were sampled from the sample honeybee colonies at each season. Samples were analyzed at Bee Protection Laboratory (BPL), Holeta Bee Research Center (HBRC), Ethiopia. Honeybee pests, namely Aethina tumida, Achrolla grisella, Ant spp, Gellaria mellonella, Spiders, Lizards, Bee Eating Birds, Mice and Honey badgers were known to exist in the study area.Comparatively, Aethina tumida, Achrolla grisella and Varroa Destructor were identified the most abundant honeybee pests. Apparent reduction in honeybee population and honey production was observed in the pest affected honeybee colonies. It is suggested that detailed and large scale study be conducted to declare the actual absence of those honeybee pests, parasites and pathogens (which were not tested positive) to help complete these study to the best of its anticipated purpose. -

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ERITREA Legend Ahferom Erob ^! Tahtay Adiyabo National Capital Gulomekeda Afar Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Red Sea Dalul Ganta Afeshum P! Adwa SaesEiea Tsatedranemba Regional Capital Amhara North WesternTahtay KoraroLaelay Maychew Kafta Humera Tahtay Maychew Werei Leke Hawzen Asgede Tsimbila Central Koneba TIGRAY Medebay Zana Naeder Adet Berahile Western Atsbi Wenberta Undetermined boundary Beneshangul Gumuz Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele P! Zone 2 International boundary Dire Dawa Tsegede Tselemt Enderta Tanqua Abergele Afdera Addi Arekay Ab Ala Tsegede Beyeda Mirab Armacho Afdera Region boundary Gambela Debark Saharti Samre Erebti Hintalo Wejirat SUDAN Abergele Tach Armacho Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Southern Zone boundary Hareri Ziquala Raya Azebo Metema Lay Armacho Wegera Wag Himra Endamehoni North Gonder Sekota Teru Chilga Woreda boundary Oromia Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Zone 4 Elidar Gaz Gibla Lake SNNPR Quara Takusa Ebenat Gulina Libo Kemkem Bugna Awra Kobo Tana Gidan Region Lasta (Ayna) AFAR Somali Alfa Ewa Fogera Farta North Wollo Semera Lay Gayint Meket Guba Lafto P! Dubti Zone 1 DJIBOUTI Addis Ababa Jawi Semen Achefer South Gonder Tigray East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Habru Aysaita AMHARA P! Dera Tach Gayint Delanta Guba Bahirdar Zuria Ambasel Debub Achefer Dawunt Worebabu Dangura Gulf of Aden Mecha West Esite Simada Thehulederie Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Afambo Dangila Kutaber Yilmana -

Land Certification and Farmers' Decision on Long Term Investment In

JOURNAL OF DEGRADED AND MINING LANDS MANAGEMENT ISSN: 2339-076X (p); 2502-2458 (e), Volume 7, Number 4 (July 2020): 2269-2278 DOI:10.15243/jdmlm.2020.074.2269 Research Article Land certification and farmers’ decision on long term investment in Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia Ermias Melaku Addis*, Mequanent Muche Amera, Gedam Birhane Biru Jimma University College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, P.O, Box 307, Jimma, Ethiopia *corresponding author: [email protected] Received 3 March 2020, Accepted 27 April 2020 Abstract: The impacts of land tenure security on investment have long been recognized. Land certification has been undertaking in most zones of the region including Jimma zone. Therefore this study assesses farmers’ perception on land certification and factors affecting long term land related investments specifically tree, fruit tree and coffee planting. It was conducted in three Woredas of Jimma Zone namely Omonada, Limmu Kossa and Seka Chekorsa. Multi-stage sampling techniques were employed to select respondent farmers from each Woreda and a total of 200 household heads, of which 79.5% are them secure land certification, were selected for the analysis. The findings’ indicates that most of the respondents have positive and strong agreements with different attributes of land certification. These are land certification encourage investment activities, soil conservation measures, and farmers to venture in area that could enhance productivity, provide increased land tenure, feel sense of ownership and current system is satisfactory, have lifelong use right and support both woman and man to share equally. There is significant relationship between land certification and long term land related investments specially tree and fruit planting. -

Prevalence of and Risk Factors For

Ophthalmic Epidemiology ISSN: 0928-6586 (Print) 1744-5086 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iope20 Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Trachoma in Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia: Results of 79 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Conducted with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project Berhanu Bero, Colin Macleod, Wondu Alemayehu, Solomon Gadisa, Ahmed Abajobir, Yilikal Adamu, Menbere Alemu, Liknaw Adamu, Michael Dejene, Addis Mekasha, Zelalem Habtamu Jemal, Damtew Yadeta, Oumer Shafi, Genet Kiflu, Rebecca Willis, Rebecca M. Flueckiger, Brian K. Chu, Alexandre L. Pavluck, Anthony W. Solomon & for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project To cite this article: Berhanu Bero, Colin Macleod, Wondu Alemayehu, Solomon Gadisa, Ahmed Abajobir, Yilikal Adamu, Menbere Alemu, Liknaw Adamu, Michael Dejene, Addis Mekasha, Zelalem Habtamu Jemal, Damtew Yadeta, Oumer Shafi, Genet Kiflu, Rebecca Willis, Rebecca M. Flueckiger, Brian K. Chu, Alexandre L. Pavluck, Anthony W. Solomon & for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (2016) Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Trachoma in Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia: Results of 79 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Conducted with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 23:6, 392-405, DOI: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1243717 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2016.1243717 © 2016 The Authors. Published with license Published online: 07 Nov 2016. by Taylor & Francis Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2068 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 19