The Cliff Dwellings of the Sierra Ancha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona TIM PALMER FLICKR

Arizona TIM PALMER FLICKR Colorado River at Mile 50. Cover: Salt River. Letter from the President ivers are the great treasury of noted scientists and other experts reviewed the survey design, and biological diversity in the western state-specific experts reviewed the results for each state. RUnited States. As evidence mounts The result is a state-by-state list of more than 250 of the West’s that climate is changing even faster than we outstanding streams, some protected, some still vulnerable. The feared, it becomes essential that we create Great Rivers of the West is a new type of inventory to serve the sanctuaries on our best, most natural rivers modern needs of river conservation—a list that Western Rivers that will harbor viable populations of at-risk Conservancy can use to strategically inform its work. species—not only charismatic species like salmon, but a broad range of aquatic and This is one of 11 state chapters in the report. Also available are a terrestrial species. summary of the entire report, as well as the full report text. That is what we do at Western Rivers Conservancy. We buy land With the right tools in hand, Western Rivers Conservancy is to create sanctuaries along the most outstanding rivers in the West seizing once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to acquire and protect – places where fish, wildlife and people can flourish. precious streamside lands on some of America’s finest rivers. With a talented team in place, combining more than 150 years This is a time when investment in conservation can yield huge of land acquisition experience and offices in Oregon, Colorado, dividends for the future. -

Habitat Use by the Fishes of a Southwestern Desert Stream: Cherry Creek, Arizona

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE FISH AND WILDLIFE RESEARCH UNIT SEPTEMBER 2010 Habitat use by the fishes of a southwestern desert stream: Cherry Creek, Arizona By: Scott A. Bonar, Norman Mercado-Silva, and David Rogowski Fisheries Research Report 02-10 Support Provided by: 1 Habitat use by the fishes of a southwestern desert stream: Cherry Creek, Arizona By Scott A. Bonar, Norman Mercado-Silva, and David Rogowski USGS Arizona Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit School of Natural Resources and the Environment 325 Biological Sciences East University of Arizona Tucson AZ 85721 USGS Arizona Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Unit Fisheries Research Report 02-10 Funding provided by: United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service With additional support from: School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona Arizona Department of Game and Fish United States Geological Survey 2 Executive Summary Fish communities in the Southwest U.S. face numerous threats of anthropogenic origin. Most importantly, declining instream flows have impacted southwestern stream fish assemblages. Maintenance of water flows that sustain viable fish communities is key in maintaining the ecological function of river ecosystems in arid regions. Efforts to calculate the optimal amount of water that will ensure long-term viability of species in a stream community require that the specific habitat requirements for all species in the community be known. Habitat suitability criteria (HSC) are used to translate structural and hydraulic characteristics of streams into indices of habitat quality for fishes. Habitat suitability criteria summarize the preference of fishes for numerous habitat variables. We estimated HSC for water depth, water velocity, substrate, and water temperature for the fishes of Cherry Creek, Arizona, a perennial desert stream. -

Area Land Use Plan

DETAIL VIEW #1 RIM TRAIL ESTATES DETAIL VIEW #2 GIRL SCOUT CAMP 260 KOHL'S RANCH VERDE GLEN FR 199 TONTO CREEK 5 THOMPSON THOMPSON DRAW I E. VERDE RIVER DRAW II BOY SCOUT CAMP FR 64 FR 64 WHISPERING PINES PINE MEADOWS BEAR FLATS FR 199 DETAIL VIEW #3 FLOWING SPRINGS DETAIL VIEW #4 DETAIL VIEW #5 DIAMOND POINT FOREST HOMES & 87 FR 29 COLLINS RANCH E. VERDE RIVER COCONINO COUNTY EAST VERDE PARK FR 64 260 FR 64 TONTO VILLAGE GILA COUNTYLION SPRINGS DETAIL VIEW #6 DETAIL VIEW #7 DETAIL VIEW #8 FR 200 FR FR 291 PONDEROSA SPRINGS CHRISTOPHER CREEK 260 HAIGLER CREEK HAIGLER CREEK (HIGHWAY 260 REALIGNMENT) COLCORD MOUNTAIN HOMESITES HUNTER CREEK FR 200 DETAIL VIEW #9 DETAIL VIEW #10 DETAIL VIEW #11 ROOSEVELT LAKE ESTATES 87 FR 184 188 OXBOW ESTATES SPRING CREEK 188 JAKES CORNER KEY MAP: LEGEND Residential - 3.5 to 5 du/ac Residential - 5 to 10 du/ac Regional Highways and Significant Roadways NORTHWEST NORTHEAST Major Rivers or Streams Residential - 10+ du/ac Gila County Boundary Neighborhood Commercial Community Commercial WEST EAST Federal/Incorporated Area Lands CENTRAL CENTRAL Light Industrial LAND USE CLASSIFICATIONS Heavy Industrial SOUTH Residential - 0 to 0.1 du/ac Public Facilities AREA LAND USE PLAN Residential - 0.1 to 0.4 du/ac DETAILED VIEWS Multi-Functional Corridor FIGURE 2.F Residential - 0.4 to 1.0 du/ac Mixed Use Residential - 1 to 2 du/ac Resource Conservation 0' NOVEMBER, 2003 3 Mi Residential - 2 to 3.5 du/ac GILA COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN - 2012 Potential Resort/Lodging Use 1 1/2 Mi GILA COUNTY, ARIZONA DETAIL VIEW #1 RIM TRAIL ESTATES DETAIL VIEW #2 GIRL SCOUT CAMP 260 KOHL'S RANCH VERDE GLEN FR 199 TONTO CREEK 5 THOMPSON THOMPSON DRAW I E. -

Initial Assessment of Water Resources in Cobre Valley, Arizona

Initial Assessment of Water Resources in Cobre Valley, Arizona Introduction 2 Overview of Cobre Valley 3 CLIMATE 3 TOPOGRAPHY 3 GROUNDWATER 3 SURFACE WATER 4 POPULATION 5 ECONOMY 7 POLLUTION AND CONTAMINATION 8 Status of Municipal Water Resources 10 GLOBE, AZ 10 MIAMI, AZ 12 TRI-CITIES (CLAYPOOL, CENTRAL HEIGHTS, MIDLAND CITY) AND UNINCORPORATED AREAS 15 Water Resources Uncertainty and Potential 18 INFRASTRUCTURE FUNDING 18 SUSTAINABLE WELLFIELDS AND ALTERNATIVE WATER SUPPLIES 19 PRIVATE WELL WATER SUPPLY AND WATER QUALITY 20 PUBLIC EDUCATION 20 ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES 21 References 23 Appendices 25 1. ARIZONA WATER COMPANY VS CITY OF GLOBE LAWSUIT 25 2. AGENT ORANGE APPLICATION IN THE 1960s 26 3. INFRASTRUCTURE UPGRADES IN THE CITY OF GLOBE 27 Initial Assessment of Water Resources in Cobre Valley, Arizona 1 Introduction This initial assessment of water resources in the Cobre Valley provides a snapshot of available data and resources on various water-related topics from all known sources. This report is the first step in determining where data are lacking and what further investigation may be necessary for community planning and resource development purposes. The research has been driven by two primary questions: 1) What information and resources currently exist on water resources in Cobre Valley and 2) what further research is necessary to provide valuable and accurate information so that community members and decision makers can reach their long-term water resource management goals? Areas of investigation include: water supply, water quality, drought and floods, economic factors, and water-dependent environmental values. Research for this report was conducted through the systematic collection of data and information from numerous local, state, and federal sources. -

Pinal Creek Trail

Pinal Creek Trail Conceptual Plan November 2012 COBRE VALLEY COMPREHENSIVE TRANSPORTATION STUDY PINAL CREEK TRAIL CONCEPTUAL PLAN Final Report November 2012 Prepared For: City of Globe and Gila County Funded By: ADOT Planning Assistance for Rural Areas (PARA) Program Prepared By: Trail graphic prepared by RBF Consulting Cobre Valley Comprehensive Transportation Study TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Study ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Study Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Study Area Overview ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Study Process......................................................................................................................................... 3 2. REVIEW OF 1992 PINAL CREEK LINEAR PARK CONCEPT ............................................................... 4 2.1 1992 Pinal Creek Linear Park Concept Report ............................................................................... 4 2.2 1992 Pinal Creek Linear Park Goals ................................................................................................. 4 2.3 Original Pinal -

John D Walker and The

JOHN HENRY PEARCE by Tom Kollenborn © 1984 John Henry Pearce was truly an interesting pioneer of the Superstition Mountain and Goldfield area. His charismatic character endeared him to those who called him friend. Pearce was born in Taylor, Arizona, on January 22, 1883. His father founded and operated Pearce’s Ferry across the Colorado River near the western end of the Grand Canyon. Pearce’s father had accompanied John Wesley Powell through the Grand Canyon in 1869. John Pearce began his search for Jacob Waltz’s gold in 1929, shortly after arriving in the area. When John first arrived, he built a cabin on the Apache Trail about seven miles north- east of Apache Junction. Before moving to his Apache Trail site, John mined three gold mines and hauled his ore to the Hayden mill on the Gila River. He sold his gold to the United States government for $35.00 an ounce. During the depression his claims around the Goldfield area kept food on the table for his family. All the years John Pearce lived on the Apache Trail he also maintained a permanent camp deep in the Superstition Wilderness near Weaver’s Needle in Needle Canyon. He operated this camp from 1929 to the time of his death in 1959. John traveled the eleven miles to his camp by driving his truck to County Line Divide, then he would hike or ride horseback to his Needle Canyon Camp. Actually, Pearce had two mines in the Superstition Wilderness— one near his Needle Canyon Camp and the other located near Black Mesa Ridge. -

Roundtail Chub Repatriated to the Blue River

Volume 1 | Issue 2 | Summer 2015 Roundtail Chub Repatriated to the Blue River Inside this issue: With a fish exclusion barrier in place and a marked decline of catfish, the time was #TRENDINGNOW ................. 2 right for stocking Roundtail Chub into a remote eastern Arizona stream. New Initiative Launched for Southwest Native Trout.......... 2 On April 30, 2015, the Reclamation, and Marsh and Blue River. A total of 222 AZ 6-Species Conservation Department stocked 876 Associates LLC embarked on a Roundtail Chub were Agreement Renewal .............. 2 juvenile Roundtail Chub from mission to find, collect and stocked into the Blue River. IN THE FIELD ........................ 3 ARCC into the Blue River near bring into captivity some During annual monitoring, Recent and Upcoming AZGFD- the Juan Miller Crossing. Roundtail Chub for captive led Activities ........................... 3 five months later, Additional augmentation propagation from the nearest- Department staff captured Spikedace Stocked into Spring stockings to enhance the genetic neighbor population in Eagle Creek ..................................... 3 42 of the stocked chub, representation of the Blue River Creek. The Aquatic Research some of which had travelled BACK AT THE PONDS .......... 4 Roundtail Chub will be and Conservation Center as far as seven miles Native Fish Identification performed later this year. (ARCC) held and raised the upstream from the stocking Workshop at ARCC................ 4 offspring of those chub for Stockings will continue for the location. future stocking into the Blue next several years until that River. population is established in the Department biologists conducted annual Blue River and genetically In 2012, the partners delivered monitoring in subsequent mimics the wild source captive-raised juvenile years, capturing three chub population. -

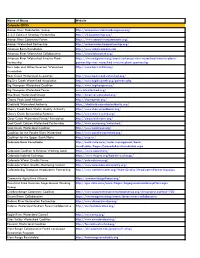

Name of Group Website Animas River Stakeholder Group Http

Name of Group Website Colorado CBCCs Animas River Stakeholder Group http://animasriverstakeholdersgroup.org/ 2-3-2 Cohesive Strategy Partnership http://232partnership.org/ Animas River Community Forum https://www.animasrivercommunity.org/ Animas Watershed Partnership http://animaswatershedpartnership.org/ Arkansas Basin Roundtable http://www.arkansasbasin.com Arkansas River Watershed Collaborative http://arkcollaborative.org/ Arkansas River Watershed Invasive Plants https://riversedgewest.org/events/arkansas-river-watershed-invasive-plants- Partnership partnership-river-watershed-invasive-plants-partnership Barr Lake and Milton Reservoir Watershed http://www.barr-milton.org/ Association Bear Creek Watershed Association http://www.bearcreekwatershed.org/ Big Dry Creek Watershed Association http://www.bigdrycreek.org/partners.php Big Thompson Watershed Coalition http://www.bigthompson.co/ Big Thompson Watershed Forum www.btwatershed.org/ Blue River Watershed Group http://blueriverwatershed.org/ Chama Peak Land Alliance http://chamapeak.org/ Chatfield Watershed Authority https://chatfieldwatershedauthority.org/ Cherry Creek Basin Water Quality Authority http://www.cherrycreekbasin.org/ Cherry Creek Stewardship Partners http://www.cherry-creek.org/ Clear Creek Watershed Forum/ Foundation http://clearcreekwater.org/ Coal Creek Canyon Watershed Partnership http://www.cccwp.org/watershed/ Coal Creek Watershed Coalition http://www.coalcreek.org/ Coalition for the Poudre River Watershed http://www.poudrewatershed.org/ Coalition for the Upper South -

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012 (Photographs: Arizona Game and Fish Department) Arizona Game and Fish Department In partnership with the Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................ i RECOMMENDED CITATION ........................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ iii DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................ iv BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 1 THE MARICOPA COUNTY WILDLIFE CONNECTIVITY ASSESSMENT ................................... 8 HOW TO USE THIS REPORT AND ASSOCIATED GIS DATA ................................................... 10 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 12 MASTER LIST OF WILDLIFE LINKAGES AND HABITAT BLOCKSAND BARRIERS ................ 16 REFERENCE MAPS ....................................................................................................................... -

Appendix a Assessment Units

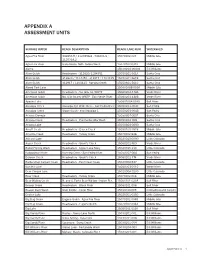

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Chapter 2 Arizona's Silver Belt ©1991 by Wilbur A

Chapter 2 Arizona's Silver Belt ©1991 by Wilbur A. Haak "Men move eternally, still chasing Fortune; and, silver nuggets and ledges of precious metals. He noted Fortune found, still wander." This quote is from Robert that these findings were located near "a butte that looks Louis Stevenson's 1883 book, The Silverado Squatters. like a hat." It was written about California, but applies just as well Thorne allegedly made subsequent visits to the area, to the nineteenth century fortune seekers in Arizona. but was unable to relocate the site. His glowing reports, They came in search of gold; silver would do, but always though, opened the door for other prospecting adventures. there was the hope, the dream, of finding gold. Many prospectors appeared in Arizona in the middle King Woolsey years of the nineteenth century. Most had failed When the Civil War broke out in 1861, most of the elsewhere - Colorado, California, Nevada, New Mexico Army was called away to fight in the east. Indian -and came to Arizona to try their luck. They were joined depredations increased, and Arizona civilians took it by soldiers, cowboys, merchants, professionals and upon themselves to play the military role. Men from all drifters. Any report or rumor of a promising claim lured walks of life joined to retaliate against the natives, men by the hundreds. A large amount of gold was found especially the "troublesome" Apaches. at various places in Arizona, but silver was the more In early January of 1864, up to 400 head of livestock prevalent precious metal, and its mining became an were reported stolen in Yavapai County. -

Gerald J. Gottfried and Daniel G. Nearyl

Hydrology of the Upper Parker Creek Watershed, Sierra Ancha Mountains, Arizona Item Type text; Proceedings Authors Gottfried, Gerald J.; Neary, Daniel G. Publisher Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science Journal Hydrology and Water Resources in Arizona and the Southwest Rights Copyright ©, where appropriate, is held by the author. Download date 02/10/2021 12:18:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/296587 HYDROLOGY OF THE UPPER PARKER CREEK WATERSHED, SIERRA ANCHA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA Gerald J. Gottfried and Daniel G. Nearyl The hydrology of headwater watersheds and river Creek watershed, and reevaluates the hypothesis basins is variable because of fluctuations in climate that Upper Parker Creek could serve as the hydro- and in watershed conditions due to natural or logic control for post -fire streamflow evaluations human influences. The climate in the southwestern being conducted on the nearby Middle Fork of United States is variable, with cycles of extendedWorkman Creek, which burned in 2000. The pres- periods of drought or of abundant moisture. These ent knowledge of wildfire effects on hydrologic cycles have been documented for hundreds of responses is low, and data from Upper Parker years in the tree rings of the Southwest (Swetnam Creek and Workman Creek should help alleviate and Betancourt 1998). Hydrologic records that the gap. The relationships for annual and seasonal only span a decade or so may not provide a true runoff volumes are of particular interest in the indication of watershed responses because the present evaluation; subsequent analyses will eval- measurements could be from a period of extreme uate relationships for peak flows.