A Phan on Phish: Live Improvised Music in Five Performative Commitments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faces and Facades” Will on Saturday, June 11, 2016 from Creates Certain Patterns, Styles and Kenya, India and Brazil; Worked Explore the Concept of Outward 5-7 Pm

ALALBANY, NY PERMIT #486 Published by the Greene County Council on the Arts, 398 Main St., Catskill, NY 12414 • Issue 110 • May/June 2016 GCCA Catskill Gallery Presents New Group Exhibition Featuring Burton C. Bell’s Graphic Novel THE INDUSTRIALIST Don’t Stereotype Me by Joanne Van Gendern. The Greene County Council narrative theme, whether through Other pieces are inspired by a books, three of which will be on miles of stone walls—enough to on the Arts presents a new group multiple images, a single image, or story, as in Matthew Pleva’s six-part display in Words and Images. reach the far side of the moon—in exhibition dedicated to the art of the story that inspired the artwork. illustration “Arrowhead,” which Reilly, a member of the Book Arts fact built by European colonists in storytelling called “Words and Abigael Puritz, a graphic depicts multiple angles of the exte- Roundtable, has given workshops a period of roughly 100 years—or Images.” Featuring the work of novelist, painter and printmaker rior of Herman Melville’s Pittsfi eld, on making books by hand in many are they perhaps much, much older? over a dozen local and international originally from Oneonta NY, depicts Massachusetts house where he libraries and museums in New York Employing a mountain of testimony artists, the Words and Images show in her graphic memoir novel “The wrote his masterpiece Moby- and New Jersey. He is currently on from archaeology, art and popular will include animated short fi lms, Climb” a memorable summer trip Dick, along with an illustrated the faculty of the Rosendale School histories, and other fi elds, Bua’s graphic novels, illustrations, sculp- to Europe. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

MIKE GORDON and the Gordonanastasio/Marshall/Herman 05 Hoodoomr

For best results, print this page out on: Note: Make sure to print actual size NEATO Glossy CD Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (ink-jet printers), or (do not choose 'Shrink to fit oversize page' option) NEATO Economatte Cd Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (laser printers) OUTSIDE BACK OUTSIDE FRONT DISC 1 Set I DISC 2 Set II 01 BestBack Reason On The ToTrain Buy (3:43) The Sun (5:54) Benevento/RussoAnastasio/Marshall 01 WelcomeDig A Pony Red (4:29) (7:57) Benevento/RussoLennon/McCartney*** 02 BeckyLove That (7:51) Breaks All Lines (3:57) Benevento/RussoAnastasio 02 ForeverPush On Night Til The Shade Day (10:34)Mary (12:24) Hidalgo/Perez#Anastasio/Lawton/Markellis 03 CleanWilson Up (3:11) Woman (9:55) Kerr/Seymour*Anastasio/Marshall/Woolf 03 ThemeGloomy From Sky (6:26) Rockford Files (6:15) Post/Carpenter##Anastasio* 04 AquiNight Como Speaks Alla To (7:21) A Woman (7:09) Rodriquez**Anastasio/Marshall 04 Mephisto46 Days (11:09) (11:25) Benevento/RussoAnastasio/Marshall 05 ThePlasma Beltless (10:45) Buckler (8:41) MIKE GORDON and the GordonAnastasio/Marshall/Herman 05 HoodooMr. Completely Voodoo (11:35)(8:37) Bennett/Bragg/Commer/Guthrie/Obialo/Stirratt/Tweedy####Anastasio BENEVENTO/RUSSO DUO 06 BigCayman Whopper Review (6:16) (7:16) Benevento/RussoAnastasio/Marshall/Herman 06 HeartbreakerThe Way I Feel (8:31) (10:04) Baldwin/Bonham/Page/Plant#### Anastasio Twi-Ro-PaSalem Armory 07 What's Done (7:33) NewSalem, Orleans, OR LA Anastasio* 07 FoamCome (12:02)As Melody (7:25) 04.30.0512.01.94 AnastasioAnastasio* THEThe Band:BAND: 08 Drifting (8:36) MikeTrey AnastasioGordon -- –bass guitar, vocals Anastasio/Lawton/Markellis Encore MarcoPeter ChwazikBenevento – bass -- keyboards JoeLes RussoHall – guitar,-- drums keyboard 09 In The Light (11:14) 08 SerpentineI Am The Walrus Fire (8:13) (8:22) Ray Paczkowski – keyboard Baldwin/Page/Plant** Burke/White/White#####Lennon/McCartney**** Recorded and Post-Production by Brad Serling (nugs.net)Skeeto Valdez – drums AllRecorded selections by copyright Paul Languedoc. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

Newly Cataloged Items in the Curriculum Library June-July 2014

Newly Cataloged Items In the Curriculum Library June-July 2014 Author Title Description Publisher Item Enum Call Number Curr Lib Teaching Aid Mautner, Diane. Word flips : Spanish / written by Diane 1 v. (unpaged) : ill. ; 28 x 17 Super Duper CURRLIB.TA. 463.71 Mautner, M.A., CCC-SLP ; edited by cm. Publications, M459wf Melanie Strait, M.S., CCC-SLP ; illustrated by Super Duper art staff. Piercy, Helen Animation Studio / Helen Piercy ; 31 pages : color illustrations CURRLIB.TA. 777.7 illustrators Mark Ruffle, MIchael Slack, and ; 25 x 18 x 6 cm. + built in P618as Katrin Wiehle. set and props. Curriculum Lib Big-Books Barton, Byron. Dinosaurs, dinosaurs / Byron Barton. 1 v. (unpaged) : col. ill. ; 37 HarperCollins Pub., CURRLIB. 028.5 x 43 cm. B293di bb Barton, Byron. Dinosaurs, dinosaurs / Byron Barton. 1 v. (unpaged) : col. ill. ; 37 HarperCollins Pub., CURRLIB. 028.5 x 43 cm. B293di bb Carle, Eric. Today is Monday / pictures by Eric Carle. 1 v. (unpaged) : col. ill., Scholastic, CURRLIB. 028.5 music ; 51 cm. + 1 big book C278ty bb idea book (21 p. : ill. ; 28 cm.) Carle, Eric. Very hungry caterpillar / by Eric Carle. 1 v. (unpaged) : col. ill. ; 37 Scholastic, CURRLIB. 028.5 x 49 cm. C278ve bb Carle, Eric. Very hungry caterpillar / by Eric Carle. 1 v. (unpaged) : col. ill. ; 37 Scholastic, CURRLIB. 028.5 x 49 cm. C278ve bb Crews, Donald. Freight train / Donald Crews. 24 p. : col. ill. ; 38 x 48 cm. Scholastic-TAB CURRLIB. 028.5 Publications, C927fr bb Ehlert, Lois. Feathers for lunch / Lois Ehlert. [40] p. : col. ill. ; 46 cm. -

Relix Magazine

RELIX MAGAZINE Relix Magazine is devoted to the best in live music. Originally launched in 1974 to connect the Grateful Dead community, Relix now features a wide spectrum of artists including: Phish, My Morning Jacket, Beck, Jack White, Leon Bridges, Ryan Adams, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Chris Stapleton, Tame Impala, Widespread Panic, Fleet Foxes, Joe Russo’s Almost Dead, Umphrey’s McGee and plenty more. Relix also offers a unique angle on the action with sections such as: Tour Diary, Behind The Scene, Global Beat, Track By Track, On The Verge and My Page as well as extensive reviews of live shows and recorded music. Each of our 8 annual issues covers new and established artists and comes with a free CD and digital downloads. TOTAL READERSHIP: 360,000+ MONTHLY PAGEVIEWS: 1.6 Million+ MONTHLY UNIQUE USERS: 280,000+ EMAIL SUBSCRIBERS: 225,000+ SOCIAL MEDIA FOLLOWERS: 410,000+ RELIX MEDIA GROUP Relix Media Group is a multifaceted, innovative, open-minded and creative resource for the live music scene. We are a passionate mix of writers, photographers, videographers, event coordinators, musicians and industry professionals. Above all, we are music lovers. Our mission is to seek out exciting, innovative performers and foster the live music community by connecting with the people who matter most: the fans. Since our earliest inception, we have opened doors for the sonically curious and sought to represent the voice of the concert community. Relix Media Group Info • relix.com • jambands.com • 3,700,000 total impressions • 375,000 total unique visitors -

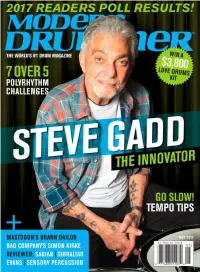

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Snarky Puppy Snarky Puppy Snarky Puppy

SNARKY PUPPY GENRE: ELECTRIC JAZZ/FUNK/INSTRUMENTAL Displaying a rare and delicate mixture of sophisticated composition, harmony and improvisation, Fusion-influenced jam band Snarky Puppy make exploratory jazz, rock, and funk. Formed in Denton, Texas in 2004, Snarky Puppy feature a wide-ranging group of nearly 40 musicians known affectionately as “The Fam,” centered around bassist, composer and bandleader Michael League. Comparable Artists: Medeski, Martin & Wood, Brad Mehldau, Weather Report, Steely Dan AWARDS • 2014 Grammy winner for “Best R&B Performance” • Voted “Best Jazz Group” in Downbeat’s 2015 Reader’s Poll/Cover of February 2016 issue •“Best New Artist” and “Best Electric/Jazz-Rock/Contemporary Group/Artist” in Jazz Times 2014 Reader’s Poll PRESS • “Emotionally heroic compositions…At the heart of Snarky Puppy’s music lies an incredible humanity,…a soulful appeal for fans of all ages” – Electronic Musician • “This 12-piece collective stands out with furious commitment to defying musical categories. The music is no joke.” – LA Times • Featured in the New York Times, NPR, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Relix, SF Weekly, Modern Drummer, and more TOUR • Played over 300 performances over the last two years on four continents • Snarky Puppy are devoted to music education holding clinics and workshops with students in-between international tourdates PEAK PERFORMANCE • Their last album, Sylva, garnered a #1-chart debut simultaneously on both Billboard’s Jazz and Heatseekers Charts • Snarky Puppy streaming music fans are primarily paid/premium subscribers to services such as Spotify, Google Play and Apple Music and listen on desktop and mobile devices (49%/51% split) • All of Snarky Puppy’s albums are recorded 100% live often with in-studio audiences present DEMO Male (82%)/Female (18%) Age: 18-34 (73%) http://www.impulse-label.com/ LINKS OFFICIAL WEBSITE 222,852 fans 30.8K followers 62.8K followers 28K 91K (Snarky Puppy) (GroundUP Music). -

Trey Anastasio

For best results, print this page out on: Supplies available from Note: Make sure to print actual size NEATO Glossy CD Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (ink-jet printers), or http://www.phish.com/drygoods (do not choose 'Shrink to fit oversize page' option) NEATO Economatte Cd Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (laser printers) OUTSIDE BACK OUTSIDE FRONT DISC 1 DISC 2 DISC 3, continued Set I Set II Set II, continued 01 Prologue (4:21) 01 Mr. Completely (10:18) 05 Ether Sunday (5:36) Music written by Trey Anastasio Anastasio Anastasio/Lawton/Markellis Orchestration by Don Hart Conducted by Trey Anastasio 02 Sing A Song* (4:25) 06 Black Dog***** (7:10) 02 Coming To (5:44) McKay/White Baldwin/Page/Plant Music written and arranged by Trey Anastasio Strings arranged by Don Hart 03 Simple Twist Up Dave (7:38) Encore Conducted by Trey Anastasio Anastasio/Marshall/Herman 07 First Tube (9:39) 03 Flock Of Words (5:21) 04 Alive Again (7:42) Anastasio/Lawton/Markellis Music written and arranged by Trey Anastasio Anastasio/Marshall/Herman Words by Tom Marshall Strings arranged by Don Hart Conducted by Paul Gambill 05 Night Speaks To A Woman (10:57) Anastasio/Marshall 04 The Inlaw Josie Wales (2:59) Music written and arranged by Trey Anastasio TREY ANASTASIO 06 Devil Went Down To Georgia** Strings Arranged by Troy Peters (3:30) Crain/Daniels/DiGregorio/Edwards/ Bonnaroo Music Festival 05 Cincinnati (Intro) (1:59) Hayward/Marshall Music written and arranged by Trey Anastasio 06.13.04 Manchester, TN Conducted by Trey Anastasio Trey Anastasio Band: 07 Curlew's Call (10:17) Russ Lawton, Dave Grippo, Jennifer 06 All Things Reconsidered (3:23) Anastasio/Marshall/Herman Hartswick, Andy Moroz, Russell Music written and arranged by Trey Anastasio Remington, Peter Apfelbaum, Ray Paczkowski, Cyro Baptista, Tony DISC 3 07 Discern (Intro) (1:57) Markellis Music written and arranged by Trey Anastasio Set II, continued Conducted by Trey Anastasio 01 Sultans Of Swing*** (5:52) Disc 1 performed by the Nashville 08 Guyute Orchestral (12:13) Knopfler Chamber Orchestra. -

HANDS on a HARDBODY IN-HOUSE ACCOUNTANT Linda Harris Sept

20!4 • 2015 SEASON C T3PEOPLE C ON OTHER STAGES BOARD OF DIRECTORS CIRCLE THEATRE CHAIR DavidG. Luther OCT 16- NOV 22 Fellowship! LIAISON, CITY OF DALLAS CULTURAL COMMISSION DALLAS CHILDREN'S THEATRE Lark Montgomery SEPT 19 - OCT 26 Rapunzel! Rapunzel! A Very Hairy BOARD MEMBERS Jac Alder, Marion L. Brockette, Jr., Fairy Tale Suzanne Burkhead, Raymond J. Clark, Katherine C. Eberhardt, Laura V. Estrada, Sally Hansen, DALLAS THEATER CENTER Victoria McGrath, David M. May, Margie J. Reese, SEPT 11 - OCT 19 The Rocky Horror Picture Show Dana W. Rigg, Elizabeth Rivera,.Eileen Rosenblum, OCT 15 - NOV 16 Driving Miss Daisy Ph.D., Scott Williams D EISEMANN CENTER FOR THE TH HONORARY BOARD MEMBERS Virginia Dykes, Gary W. Grubbs, John & Bonnie Strauss PERFORMING ARTS NORMA YOUNG ARENA STAGE 2014-2015 OCT 11 Steppin' Out Live with Ben Vereen ADMINISTRATION OCT 13 The Miracle ofMozart! EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Jac Alder OCT 16-19 Endurance! CAN DY BARR'S LAST DANCE MANAGING DIRECTOR Marty Van Kleeck > Aug. 7-31 DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS a[COMMUNICATIONS JUBILEE THEATRE e:::: a world premiere comedy by Ronnie Claire Edwards Kimberly Richard SEPT 26- OCT 26 The Brothers Size LI.J IT MANAGER Nick Rushing KITCHEN DOG THEATRE CPA Ron King SEPT 19 - OCT 25 Thinner Than Water <( U HANDS ON A HARDBODY IN-HOUSE ACCOUNTANT Linda Harris Sept. 25-0ct. 19 DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH Sarah Drake POCKET SANDWICH THEATRE OCT 3 - NOV 15 Phantom ofthe Opera: The z EXECUTIVE ADMlNSTRATIVE ASSISTANT a musical by Doug Wright, Amanda Green, & Trey Anastasio Melodrama - Z Kat Edwards HOUSEKEEPING Kevin Spurrier SHAKESPEARE DALLAS 0 � A CIVIL WAR CHRISTMAS PRODUCTION SEPT 17 - OCT 12 Antony (f{.Cleopatra Nov. -

Outside Front Outside Back

For best results, print this page out on: Note: Make sure to print actual For best results, print this page out on: NEATO Glossy CD Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (ink-jet printers), or size (do not choose 'Shrink to fit NEATO Glossy CD Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (ink-jet printers), or NEATO Economatte Cd Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (laser printers) oversize page' option) NEATO Economatte Cd Labels, Booklet, and Tray liners (laser printers) OUTSIDE BACK OUTSIDE FRONT DISC 1 DISC 2 DISC 3 Set I Set I (cont’d) Set II (cont’d) 01 Punch You In The Eye (8:35) 01 Julius (8:40) 01 Halley’s Comet (6:33) Anastasio Anastasio/Marshall Wright 02 Backwards Down The Number Line (8:00) Set II 02 2001 (6:07) Anastasio/Marshall Deodato*** 02 Down With Disease (19:23) 03 Axilla I (3:26) Anastasio/Marshall 03 David Bowie (11:00) Anastasio/Marshall/Herman Anastasio 03 Piper (9:14) 04 Taste (9:07) Anastasio/Marshall Encore Anastasio/Fishman/Gordon/McConnell/Marshall 04 Fluffhead (15:04) 04 Character Zero (6:48) 05 Boogie On Reggae Woman (5:45) Anastasio/Pollak Anastasio/Marshall Wonder* 05 Cities (6:49) 06 Stash (11:45) Byrne** Anastasio/Marshall 06 Free (7:05) Madison Square Garden 07 Lawn Boy (3:06) Anastasio/Marshall New York, New York Anastasio/Marshall 12.03.09 PHISH: Trey Anastasio, Jon Fishman, 08 Time Turns Elastic (15:21) Mike Gordon, Page McConnell Anastasio Recorded by Timothy Powell 09 Back On The Train (7:03) Post-Production by Micah Gordon Anastasio/Marshall Phish Inc.