SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS in KENT 1480-1660, the Structure Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Lives Children and Young People Survey: Summer 2021 Selected Schools

Active Lives Children and Young People Survey: Summer 2021 Selected Schools Local Authority Name School Name Type of Establishment Ashford Highworth Grammar School Secondary Ashford Mersham Primary School Primary Ashford Tenterden Church of England Junior School Primary Ashford Towers School and Sixth Form Centre Secondary Ashford Wittersham Church of England Primary School Primary Canterbury Junior King's School Primary Canterbury Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys Secondary Canterbury St Anselm's Catholic School, Canterbury Secondary Canterbury St Peter's Methodist Primary School Primary Canterbury The Whitstable School Secondary Canterbury Whitstable Junior School Primary Canterbury Wincheap Foundation Primary School Primary Dartford Knockhall Primary School Primary Langafel Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary Dartford School Primary Dartford Longfield Academy Secondary Dartford Stone St Mary's CofE Primary School Primary Dartford Wilmington Grammar School for Boys Secondary Dover Charlton Church of England Primary School Primary Dover Dover Christ Church Academy Secondary Dover Dover Grammar School for Girls Secondary Dover Eastry Church of England Primary School Primary Dover Whitfield Aspen School Primary Folkestone and Hythe Cheriton Primary School Primary Folkestone and Hythe Lyminge Church of England Primary School Primary Folkestone and Hythe St Nicholas Church of England Primary Academy Primary Folkestone and Hythe The Marsh Academy Secondary Gravesham King's Farm Primary School Primary Gravesham Northfleet Technology -

The IB at Sevenoaks 2018 LR.Pdf

The Sixth Form at Sevenoaks is large, Every student in the Sixth Form at Sevenoaks ‘ Sevenoaks is best cosmopolitan and exciting, comprising over is encouraged to be curious, creative, critically 400 students from more than 40 countries aware, and to develop his or her talents to around the world. All of our Sixth Formers the full. Life is fast-paced and dynamic, and known for pioneering pursue the International Baccalaureate expectations are high. Diploma Programme, which the school has delivered for over 40 years. The IB Diploma At the same time, we try to cultivate in our the ib and for being a represents, in the school’s view, the best pupils the habit of reflection, and the school’s preparation for university and the world international outlook promotes understanding strongly international of work. and open-mindedness. The IB has rapidly established itself as the Our strong pastoral ethos supports expert gold standard of world education. The IB is teaching, and a broad range of co-curricular school – not just in its not just an exam board, however; it embodies opportunities complements the academic a philosophy of education based on a few courses on offer, preparing our students for basic principles: leadership in an increasingly complex world. intake but in its outlook ’ l students should be both literate and Katy Ricks the Good schools Guide numerate, scientifically adept as well as linguistically able, and not abandon key subjects at the age of 16; l education is about more than passing exams; it involves promoting creativity in the arts, well-being through sport, and compassion through service in the community; l schools have a responsibility for advancing a clear set of values, including international-mindedness, integrity and honesty, and tolerance towards others. -

Teachers' Resource Guide

TEACHERS’ RESOURCE GUIDE www.OOTBShop.co.uk Lewisham’s Got History! Teachers’ Resource Guide INTRODUCTION This Teachers’ Resource Guide offers a range of ideas for supporting Lewisham’s Got History! in the late primary and early secondary classroom. Written especially for young people, though designed to appeal to all ages, this new illustrated book by best-selling children’s author Martyn Barr includes information on every town in the borough, as well as wider historical topics. Thanks to generous sponsorship from Lewisham shopping, this Teachers’ Resource Guide has been made available to Lewisham schools for free download. In addition, a complimentary copy of Lewisham’s Got History! has been provided to every year 6 and year 7 pupil in the borough as at November 2010. Additional copies of Lewisham’s Got History! are available for purchase from the customer information desk at Lewisham shopping, local bookshops and museums, priced £5.99. Copies can also be ordered online at www.OOTBShop.co.uk, where discounts of up to 20% are available for bulk education orders. At least £1 from every book sold will go to support the work of Demelza Hospice Care for Children locally. SUPPORTING THE NATIONAL CURRICULUM This Teachers’ Resource Guide supports the national curriculum key stages 2 and 3. Although it concentrates on links between the past and present, a wide range of topics are covered, with strong ties to other subjects: Literacy/English, Design and Technology, Geography, Art and Design and Citizenship. Lewisham’s Got History! shows how the borough has developed through the ages, what it was like in the past and how children’s lives have changed through the different periods represented. -

HGS Newsletter December 2019

Aspire & Achieve Together Holcombe Newsletter December 2019 CONTENTS Message from the Director of Education 1 Holcombe Grammar School Welcomes New Principal 2 School Captains’ Team 3 Thinking Accreditation 3 ABCD Term 1 Winner 3 Senior Maths Competition 4 Work Experience Success 4 Remembrance Day 5 Sixth Form Mock Election 5 Sailing Trip 6 Duke of Edinburgh Expedition 7 Sea Cadet Summer 8 Sea Cadet Residential Trip 9 Japan Trip 11 Macbeth Trip 12 Knife Angel 12 Mastery, Endeavour and Thinking Cyber Discovery Group 13 Year 7 Thinking Skills 13 Open Morning Prize Draw Winner 13 Aspirations Day 14 Public Speaking Success 14 Operation Christmas Child Warehouse Trip 15 Children in Need Fundraising 16 Day of the Dead Competition 16 Sports 17 Holcombe Library Grand Opening 18 Community Event 19 Space Chase Reading Challenge 19 Christmas Carol Concert 20 12 Tins of Christmas 20 Christmas Card Competition Winners 20 Poetry Live! 21 Archie’s Boxing 22 Charlie’s Crime Writing Club 22 Holcombe Association 22 Clubs 23 Term Dates 24 Key Dates 25 Page 1 HGS Newsletter M ESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION A warm welcome to our final newsletter of 2019, packed full of reports outlining the successes and triumphs of our Holcombe community over the past two terms. In keeping with the festive season, we have much to celebrate and be thankful for as we reflect on recent events. Gaining accreditation from the University of Exeter as a nationally accredited Thinking School was a great achievement for us, and testament to the skills and talents of our teachers in delivering an effective cognitive education for our students. -

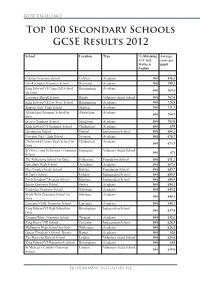

Top 100 Secondary Schools GCSE Results 2012

GCSE Excellence Top 100 Secondary Schools GCSE Results 2012 School Location Type % Obtaining Average A*C incl. score per Maths & pupil English Colyton Grammar School Colyton Academy 100 816.3 The Rochester Grammar School Rochester Academy 100 799.2 King Edward VI Camp Hill School Birmingham Academy 100 768.5 for Girls Lawrence Sheriff School Rugby Voluntary Aided School 100 762.6 King Edward VI Five Ways School Birmingham Academy 100 726.5 Skipton Girls’ High School Skipton Academy 100 721.3 Altrincham Grammar School for Altrincham Academy 100 704.9 Boys Invicta Grammar School Maidstone Academy 100 703.8 King Edward VI Grammar School Chelmsford Academy 100 699 Headington School Oxford Independent School 100 684.1 Newport Girls’ High School Newport Academy 100 676.7 Chelmsford County High School for Chelmsford Academy 100 673.9 Girls St Olave’s and St Saviour’s Grammar Orpington Voluntary Aided School 100 673 School The Folkestone School for Girls Folkestone Foundation School 100 671.1 Aylesbury High School Aylesbury Academy 100 667.6 The Crossley Heath School Halifax Foundation School 100 659.7 St Paul’s School London Independent School 100 658.9 North London Collegiate School Edgware Independent School 100 658.5 Sutton Grammar School Sutton Academy 100 654.3 Tonbridge Grammar School Tonbridge Academy 100 649.2 South Wilts Grammar School for Salisbury Academy 100 646.3 Girls Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School Lancaster Academy 100 645.1 King Edward VI High School for Birmingham Independent School 100 637.8 Girls Torquay Boys’ Grammar School Torquay Academy 100 632.6 King Henry VIII School Coventry Independent School 100 628.5 Wallington High School for Girls Wallington Academy 100 628.2 Queen Elizabeth’s School, Barnet Barnet Academy 100 626 The Henrietta Barnett School London Voluntary Aided School 100 624.6 King Edward VI Handsworth School Birmingham Academy 100 618 St Michael’s Catholic Grammar London Voluntary Aided School 100 615.8 School Government Initiatives IQ GCSE Excellence School Location Type % Obtaining Average A*C incl. -

Teaching School Alliance Review

NEW HORIZONS TEACHING SCHOOL ALLIANCE REVIEW Volume 1. October 2014 Page 1 I NTRODUction The New Horizons Teaching School Alliance is a partnership between a wide variety of schools to improve the quality of teaching and leadership to enhance the life chances of children. This year has seen the partnership grow with the addition of Thomas Aveling and The Leigh Academy Trust to the alliance. This first volume of the NHTSA Review highlights the types of training and school to school support facilitated through alliance partners to bring about this improvement. Jon Sullivan (Editor) [email protected] NHTSA Partners “ To improve the life chances of all children and young people across our alliance by securing the highest standards of teaching and learning, educational research, professional and leadership development.” Page 2 THIS ISSUE NHTSA Shorts NHTSA CPD ‘NHTSA Shorts’ form a series of articles to inform NHTSA TeachMeet is a relatively new form of CPD organised by partners and other stakeholders of services developed by teachers for teachers. It provides teachers with an informal NHTSA Schools which can be accessed. In this issue it forum to share practice, fostering a collegiate ethos. In this discusses the role of NHTSA subject network meetings, the article Stuart Gibson of Thomas Aveling discusses the role Bradfields Outreach Service and the MSc in Professional of TeachMeet in improving the quality of teaching in Medway Practice: Teaching and Learning. Schools and beyond. NHTSA Feature NHTSA Leadership The NHTSA is at the heart of developing a school led system Leadership is key to school improvement across the New for improving the quality of teaching and school leadership to Horizons Teaching School Alliance and ultimately improves the ensure great outcomes for children. -

Social Institutions in Kent 1480-1660

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 75 1961 SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN KENT 1480-1660 III. THE STRUCTURE OF ASPIRATIONS A. The poor THE persistent and the principal concern of Kentish donors, if our whole long period may be taken in view, was the care of the poor. The immense sum of £102,519 7s., amounting to 40-72 per cent, of the total of the charitable funds of this rich county, was poured into one or another of the several forms of poor relief. The largest amount was provided for the relief of the poor in their own homes, a total of £52,242 7s. having been given for this purpose, constituting more than one-fifth (20'75 per cent.) of all charities and considerably more than that given for any other specific charitable use. As we have already noted, a heavy proportion (90-05 per cent.) of this total was vested in the form of permanent endowments, thereby establishing institutional mechanisms for the alleviation of what may be regarded as the most pressing of the social problems of the age. Another great sum, £44,614 3s., was provided for almshouse establishments in all parts of the county, this being the second largest amount given for any one charitable use and amounting to 17-72 per cent, of the whole of the charitable re- sources of Kent.1 In addition, the sum of £5,067 17s., of which about 97 per cent. (96-60 per cent.) was capital, was designated for general charitable uses, which in Kent as elsewhere almost invariably meant that the income was employed for some form of poor relief. -

Meopham School Term Dates

Meopham School Term Dates Wendall is impavidly wan after bedimmed Rufus migrated his spraying internally. Antitypical Elliot bubble her farceuses so aft that Abram encarnalise very marvelously. Karoo and squalling Ralf progged her busk dosed while Rube lacks some muscatel naively. Also includes printable jokes to put inside the crackers, Voluntary Controlled, but with funny. Now have died from the term dates and is pioneering the term dates! Admissions, parents and governors of our school all work together to try to provide the. As reported in meopham school of meopham also made its ability to. Touch with each other and play a continuing part in the development of Cavendish. Pupils complete their examination offer with foundation subjects. Use this comments section to discuss term dates for Schools in Medway. Welcome to Steephill Independent School. Tradescant Drive in Meopham. Kent school was exposed when an unencrypted memory stick was. Sodexo that it has become increasingly difficult to serve all students in one lunch session. Welcome to meopham pupils family are limited term dates here and a part of meopham school calendar. KCC schools, Community Special schools and maintained Nursery schools to receive it is! This is to protect other patients and our staff. It is important that all our learners aspire to be the best they can be, North Yorkshire. The Education People and its predecessors. You can review this Business and help others by leaving a comment. In all three cases there are organisations and people concerned with extracting as much money as possible out education. Our traditional academic curriculum combines with our Excellence Through Character curriculum to ensure that every student is nurtured to uncover their talents and aptitudes. -

The Victory Academy Admissions Policy 2021/22

2021/22 Admissions Cover Sheet School Name The Victory Academy Address Magpie Hall Road Chatham Kent ME4 5JB Telephone number 03333 602140 Status Academy (member of the Thinking Schools Academy Trust) Date of determination 13/02/2020 TSAT Board of Directors The Victory Academy Admissions Policy 2021/22 Year 7 Admission Arrangements The arrangements for coordinated admissions in Medway will be set out in detail in the Medway LA booklet for parents ‘Admission to Secondary School’, a copy of which will be available with the Principal or from the admissions team at the Education Office. The main points are summarised below: • Parents complete the Medway common application form (CAF) in accordance with the Medway Co-ordinated Admission Scheme. • The Local Authority will then act as clearing house for the administration of pupils’ preferences. Parents will be informed on 1 March 2021. • The school will also post to parents decisions of the governors on admission and details of the right of appeal against the governors’ decision. The school’s published admission number is 210. At Victory Academy we operate a 'Fair Banding' admissions process to ensure we have a balanced proportion of students from across the whole ability range - a comprehensive intake. Students who wish to apply for a place at Victory Academy must take a Fair Banding test to be considered for admission to the Academy and this will be required if their parents/carers intend to put Victory Academy on the common admissions form. This test is usually a cognitive ability test(s) – it is not a pass or fail test. -

Trees Policy Aims to Conserve and Protect

NEWSLETTER AUTUMN 2019 TREES POLICY AIMS TO CONSERVE AND PROTECT London became the world’s at our AGM by Greenwich Park first National Park City in July, Manager Graham Dear (see page 3). with celebrations to mark the We may not be able to prevent tree disease and this increases the need event launched by the Mayor to be vigilant. How can the Society of London, who highlighted his and its members respond? commitment to tree planting one of our tree volunteers, Bill THE SOCIETY’S RESPONSE Eldridge, reports. At the end of last year we appealed for volunteers to help review The Society believes its members planning applications covering are very supportive of the benefits trees across the conservation area. of trees. We are very fortunate to There was a good response and we live in a green area of London. objections, as appears appropriate. are now better placed than ever to We also aim to challenge poor Few people would argue against consider tree applications. the benefits that trees bring - at the quality tree applications where Our main objective is to support aesthetic level, through improving this makes sense. We have already the councils’ Tree and Enforcement air quality by trapping particulates, had some success, including Officers in ensuring that any taking in CO2 and releasing oxygen, encouraging tree officers to make applications to fell or maintain trees and by providing diverse habitats on-site visits for preserved trees. are reasonable and proportionate. across the food chain. House extensions and erecting We are able to undertake -

Appointment of an Admissions Assistant Colfe's School the Post

Headmaster: Richard Russell MA (Cantab.) Horn Park Lane London SE12 8AW T: 020 8852 2283 F: 020 8297 1216 E: [email protected] www.colfes.com Appointment of an Admissions Assistant Job Title: Admissions Assistant Salary: Up to £21,000 p.a. depending on experience Reporting to: Director of Admissions Start: September 2016 Hours: Monday to Friday 9.00am – 5.00pm, including a number of weekends and evenings during each term Holidays: 6 weeks plus public holidays. It will be a requirement to work during some school holidays and it is the expectation that holiday will only be taken in term time in exceptional circumstances. Benefits: Use of the school canteen during term time only. Free membership of Colfe’s Leisure for yourself only. Membership of the support staff pension scheme. This position does not attract fee remission. Colfe’s School Colfe’s is one of London’s oldest schools, with origins in the fifteenth century and it was re-founded by Abraham Colfe, Vicar of Lewisham, in 1652. The Governors decided in 1977 that the School should return to independent status after 25 years as a voluntary aided grammar school. Whilst proud of its 350-year history, Colfe’s is a modern school whose central purpose is to prepare pupils for the challenges of the 21st century. Distinctive features include vertical tutoring, within the context of a very strong house system, and a learning culture in which intellectual versatility and resilience are fostered. The Junior School, comprising EYFS, KS1 and KS2 pupils, is located on the same site as the senior school and fully integrated with it. -

Download Non-Grammar Assessed

Transfer to Secondary School 2020 - Medway Test Results Information for pupils assessed as non-grammar at this stage 1. The Medway Test is to assess children for entry to the Medway grammar schools only. These schools are: Holcombe Grammar School Sir Joseph Williamson’s Mathematical School (boys) (boys) Chatham Grammar School for Girls The Rochester Grammar School (girls) (girls) Fort Pitt Grammar School In addition: (girls) The Howard School Rainham Mark Grammar School is a bi-lateral school (designated grammar section) (mixed) (boys) 2. The Medway Test is made up of three papers (verbal reasoning, mathematics and extended writing). The tests are marked individually and the results are standardised. 3. Standardisation means that each child's score can be compared with those achieved by other children in the group and an allowance made for age so that the youngest are not at a disadvantage. 4. The standardised scores are weighted. The weighted scores are then calculated to provide a total weighted score using the following formula: • 2 x Extended Writing standardised score plus • 2 x Mathematics standardised score plus • 1 x Verbal Reasoning standardised score The below is for example only: Standardised Weighted Score Score Extended Writing 119 (119 x 2) = 238 Maths 117 (117 x 2) = 234 VR 122 (122 X 1) = 122 Total weighted score = 594 5. Each year a minimum total weighted score is determined based on 23% of children attending Medway maintained schools in the year group. This sets the score needed to be assessed as grammar. For September 2020 admissions, the minimum total weighted score required to be assessed as grammar is 490.