5. Leaving Neverland: How Did We Get Here?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Courses at Wellesley and Workshops

EXPLORE THE WORLD OF PEOPLE AND IDEAS Zombinomics Pandemic! Outbreak! Go! Post-Apocalyptic Economics Bacterial Epidemiology E-20 Summit Fix It + Flip It Crime Squad So, You Want to Be a Doctor? World Economics Interior Remodeling Design Criminal Investigations Medical Careers THIS GUIDE IS FOR REFERENCE ONLY Cupcake Armada Processing Makes Perfect Perfect Pixels Flying Ninjas Cupcake ChallengesThe coursesComputer and Programming workshops listedIntro toin Digital this Photography guide were offeredAerial Robotics during the summer of 2017. While we will offer a similar range of courses and workshops in 2018, specific options may change. 2018 options will be published later in the fall. Sing It? Bring It! The Wig + the Wardrobe Pigskin Payoff Accessorize This! Pop Choir Music Costume, Hair + Make-up Design Business of Sports Intro to Accessory Design Sky Scraping Race on Mars! Manufacturing Mario Cooks Unhooked Commercial Architecture Exploratory Robotics Conceptual Video Game Design Cooking Challenges 2017 Courses and Workshops at Wellesley EXPLO 360 at Wellesley: Courses Summer 2017 EXPLORE THE WORLD OF PEOPLE AND IDEAS… AND DISCOVER YOUR PLACE IN IT Step out of your comfort zone and explore the world of people and ideas. Whether you’re an expert in algebra, basketball, or ceramics, – or whether you’ve only imagined being a fashion Curriculum Innovation designer, a sports agent, or a crime scene scientist, – EXPLO lets at EXPLO you dive into what you love as well as what you dream about. The choice is all yours. Our curriculum team spends 10 months a year The courses and workshops at EXPLO 360 at Wellesley are your planning and preparing opportunity to develop and express your natural talents or explore new the hundreds of courses interests and skills in a pressure-free environment (That’s right — and workshops that EXPLO no grades!) with other students offers each summer. -

Primates Don't Make Good Pets! Says Lincoln Park

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EDITOR’S NOTE: Photos of an appropriate multi-male, multi-female group of chimpanzees at Lincoln Park Zoo can be found HERE. Pet trade images are not shared as Lincoln Park Zoo research shows when these images of chimpanzees in human settings are circulated, chimpanzees are not believed to be endangered. Primates Don’t Make Good Pets! Says Lincoln Park Zoo Series of manuscripts from the Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes bring light to the detrimental effects of atypically-housed chimpanzees Chicago (December 13, 2017) – The Wolf of Wall Street movie. Weezer’s “Island in the Sun” music video. Michael Jackson’s “pet” Bubbles. While these may seem like unrelated pop culture references, they all have a similarly daunting theme: the use of chimpanzees in the pet or entertainment trade. These chimpanzees typically are raised by humans and rarely see others of their own species until they are fortunate enough to be moved to an accredited zoo or sanctuary. For years, Lincoln Park Zoo researchers have documented the long-term effects of this unusual human exposure on chimpanzees. Now, a third and final study in a series has been published in Royal Society Open Science Dec. 13 showcasing the high stress levels experienced by these chimpanzees who have been raised in human homes and trained to perform for amusement. Over the course of the three years, Fisher Center researchers evaluated more than 60 chimpanzees – all now living in accredited zoos and sanctuaries - and examined the degree to which they were exposed to humans and to their own species over their lifetime to determine the long-term effects of such exposure. -

Michael Jackson Betwixt and Between: the Construction of Identity in 'Leave Me Alone' (1989)

Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1: Literature Review 4 1.1: Past Research: On Michael Jackson Studies 4 1.2: Disability Studies 4 1.2.1: The Static Freak/Plastic Freak 6 1.3: Defining the Liminal 7 1.4: Postmodern Theory: The Social Construction of Identity 8 Chapter 2: Methodology 10 Chapter 3: Analysis 12 3.1: Narrative Structure of ‘Leave Me Alone’ 12 3.2: Media Narratives in ‘Leave Me Alone’ 13 3.3: The Static Freak/Plastic Freak in ‘Leave Me Alone’ 15 3.4: Liminal Identity: Temporary Phase/Permanent Place 16 3.5: Postmodern Subjects: The Aesthetics of the Collage 17 3.6: Identity and Postmodernism: The Problem With Disability Studies 18 Chapter 4: Conclusion 20 Bibliography 22 Attachment 1: Images 24 Attachment 2: Shotlist ‘Leave Me Alone’ 27 1 Introduction ‘The bottom line is they don’t know and everyone is going to continue searching to find out whether I’m gay, straight, or whatever … And the longer it takes to discover this, the more famous I will be.’1 * * * ‘Michael’s space-age diet’, ‘Bubbles the chimp bares all about Michael’, ‘Michael proposes to Liz’, ‘Michael to marry Brooke’. These may look like part of the usual rumors about Jackson frequently appearing in the media, however, they are not. Instead, these headlines are the opening scene of the music video for Jackson’s song ‘Leave Me Alone’, released on January 2, 1989, and directed by Jim Blashfield. Jackson opens by singing the words: I don't care what you talkin' 'bout baby I don't care what you say Don't you come walkin' beggin' back mama I don't care anyway ‘Leave Me Alone’ is a response to the rumors that began to circulate in the media after the worldwide success of Jackson’s 1982 album Thriller. -

Honors Curriculum Sheet

Honors Program Course Offerings, Updated as of 8/14/2020 Fall Quarter, 2020-2021 Course Day/Time Instructor HON 101 - World Forbidden Knowledge Wed: Mark Arendt Literature Are there limits to what we should know? From Chaucer, in The Wife of 11:20AM-12:50PM Bath’s Tale, “Forbede us thing and That desiren we,” to Lou Reed’s Modality: Transformer album, “Hey babe, take a walk on the wild side,” literature is Online-Hybrid replete with transgressors and transgressions. In this course students will study the subject of forbidden knowledge as it is expressed in classic and contemporary works of fiction, poetry and drama – from portions of Milton’s Paradise Lost to Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son and Mary Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior. HON 101 - World Masterpieces of Japanese Women Tues/Thurs: Heather Bowen-Struyk Literature This course begins over 1000 years ago with masterpieces of world 1:00PM-2:30PM literature. In contrast to other national literary canons, the great works of Modality: classical Japan were written by women in the imperial court. In this course, Online-Sync we will travel the socio-historical distance from the women of classical court literature to Raichō and her coterie of bluestocking feminists and beyond, to our own time, with a self-reflexive novel by Japanese-Canadian Buddhist Ruth Ozeki. Through readings of poetry, diaries, and fiction, this course offers an introduction to important issues for discussing literature including gender and sex, class and labor, ethnicity and race, and diaspora and national identity. HON 102: History in The Arabian Nights in World History Wednesday: Warren Schultz Global Contexts Chances are we have all heard of Aladdin, Ali Baba, Genies, and Sinbad the 9:40AM-11:10AM Sailor, but how well do we really know them? This course explores the Modality: history of the famous collection of tales from which these characters are Online-Hybrid commonly assumed to have inhabited, the Book of the Thousand and One Nights. -

Tom Messeresu Talks About June Chandlers Testimony

Tom Messeresu Talks About June Chandlers Testimony Leo is revengingly volatilizable after presentational Connolly reacquaints his lobotomy tauntingly. Stannic and grizzled Gordie battling his embarcations reimport possesses Romeward. Cercarian and spouseless Morgan fishtails aslope and horn his myosis rather and hypodermically. The chandlers had abandoned them to be guilty about that twelve jurors sat through june about how do not been used any After leaving neverland, anywhere else and tom messeresu talks about june chandlers testimony earlier and ron zonen, charles thomson noted that is michael he had his accusers. How the prosecution never grew jealous of thousands of allowing mr jackson was approached them into the arch rival jamie king of tom messeresu talks about june chandlers testimony of the fbi continued media. Michael jackson was not okay, it is michael was a classic example of the street by a past. It hard copy at the bashir know? That idea for tom messeresu talks about june chandlers testimony into counseling until after the last time with all findings and in and calculating nature. Oprah winfrey why did the pursuit of tom messeresu talks about june chandlers testimony stand she believed him pretty big chink for money was true, you will and hiding place? Tom sneddon enlisted the chandlers charge dr testifies that tom messeresu talks about june chandlers testimony of the. Chacon who only person in tickling to tom messeresu talks about june chandlers testimony? Dr testifies for all of all customer reviews to portray michael then this place only with tom messeresu talks about june chandlers testimony. This case against. -

98.6: a Creative Commonality

CONTENT 1 - 2 exibition statement 3 - 18 about the chimpanzees and orangutans 19 resources 20 educational activity 21-22 behind the scenes 23 installation images 24 walkthrough video / flickr page 25-27 works in show 28 thank you EXHIBITION STATEMENT Humans and chimpanzees share 98.6% of the same DNA. Both species have forward-facing eyes, opposing thumbs that accompany grasping fingers, and the ability to walk upright. Far greater than just the physical similarities, both species have large brains capable of exhibiting great intelligence as well as an incredible emotional range. Chimpanzees form tight social bonds, especially between mothers and children, create tools to assist with eating and express joy by hugging and kissing one another. Over 1,000,000 chimpanzees roamed the tropical rain forests of Africa just a century ago. Now listed as endangered, less than 300,000 exist in the wild because of poaching, the illegal pet trade and habitat loss due to human encroachment. Often, chimpanzees are killed, leaving orphans that are traded and sold around the world. Thanks to accredited zoos and sanctuaries across the globe, strong conservation efforts and programs exist to protect and manage populations of many species of the animal kingdom, including the great apes - the chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan and bonobo. In the United States, institutions such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the Species Survival Plan (SSP) work together across the nation in a cooperative effort to promote population growth and ensure the utmost care and conditions for all species. Included in the daily programs for many species is what’s commonly known as “enrichment”–– an activity created and employed to stimulate and pose a challenge, such as hiding food and treats throughout an enclosure that requires a search for food, sometimes with a problem-solving component. -

Leaving Neverland: Michael Jackson and Me: Channel 4, 6 & 7 March 2019

Ofcom ref: 00733152 Julia Snape Email: [email protected] 16 July 2019 Leaving Neverland: Michael Jackson and Me: Channel 4, 6 & 7 March 2019 Thank you for your request for information regarding Ofcom’s consideration of complaints about the above programme. Your request was received on 24 June 2019. You have asked a number of questions, which we set out below. To the extent that you have asked for recorded information which is held by Ofcom, we have considered those requests in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (‘the Act’). Your questions: “1) Full reasoning and explanation as to why Ofcom ruled against complaints relating to the showing of the 'Leaving Neverland' documentary aired by Channel 4 on 6/3/19 and 7/3/19. 2) An explanation as to why Ofcom failed to act on the large number of public complaints about this programme, which was clearly exposed as a 'witch hunt' against an individual who can no longer defend himself even before the programme was aired, full of lies and inaccuracies. 3) What investigation was carried out by Ofcom in relation to the complaints made against the programme? 4) Since these complaints of standard and factual inaccuracy were submitted to Ofcom, what procedures were carried out by Ofcom in order to ascertain whether further investigation was required? 5) Since at least several complaints were made with specific reference to Ofcom's own Code of Conduct (which the programmes clearly breached on numerous occasions), why did Ofcom adjudicate against these complaints and in favour of a programme which material and ethos was in breach of said Code of Conduct? 6) All correspondence, documents, notes, reports and transcripts of any telephone calls, and all e-mails relating to the enquiry into the 'Leaving Neverland' programmes”. -

For Musicians

THE ULTIMATE GUIDE FOR MUSICIANS TURN YOUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL INTO A PROMOTION ENGINE THAT MAKES YOU MONEY THE ULTIMATE YOUTUBE PROMOTION GUIDE FOR MUSICIANS: How to Turn Your YouTube Channel Into an Engine That Makes You Money CONTENTS YouTube: home to cute cats, inane The Beginner’s Glossary of Basic memes, and the most revolutionary YouTube Terminology music-discovery platform in history! YouTube is quickly becoming the world’s most popu- How to Make a YouTube Channel That lar search engine for music. Think about it: whenever Engages Your Audience and Encourages your friend recommends a new band, whenever you Music Sales have a craving to hear a rare oldie, whenever you want to see if a musician can put on a good live show, where 10 Kinds of Music Videos to Promote do you turn? YouTube. Your Music At least that’s where millions of people are turning every day. Promote Your Music with YouTube Playlists For today’s independent musician, having a strong video presence is practically a requirement for a Enhance Your Video with successful DIY music career. YouTube videos are YouTube Annotations easily accessible and easily shareable across blogs, websites, and social networks. But it’s not always clear 5 Tips to YouTube Promotion how a YouTube view translates into albums sales or concert attendance. This guide addresses some of those mysteries. Stream Your Songs — Every Single One! YouTube is one of the most effective music promotion Earn Money from Your Music Videos machines ever, and we want you to use it to its fullest. CD Baby has put together this guide to help you with Earn More Money from YouTube: Host a the nuts and bolts, from coming up with a great video Video Contest concept to collecting the check for your music’s usage on YouTube! 1 The Ultimate YouTube Promotion Guide for Musicians The Beginner’s Glossary of Basic what the annotations say and where, when, and how they YouTube Terminology appear (and disappear) while the video plays. -

The-Stinging-Fly-42V2-Sampler.Pdf

‘… God has specially appointed me to this city, so as though it were a large thoroughbred horse which because of its great size is inclined to be lazy and needs the stimulation of some stinging fly…’ —Plato, The Last Days of Socrates A sampler of work from Issue 42 Volume Two Summer 2020 Editor: Danny Denton Publisher: Declan Meade Assistant Editor: Sara O’Rourke Poetry Editor: Cal Doyle Eagarthóir Filíochta: Aifric MacAodha Reviews Editor: Lily Ní Dhomhnaill Online Editor: Ian Maleney Contributing Editors: Dan Bolger, Mia Gallagher, Lisa McInerney, Thomas Morris and Sally Rooney The Stinging Fly gratefully acknowledges the support of The Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon. A Note on Navigation: Please feel free to scroll freely through these pages. From the contents page – coming up next – you can also click through to particular stories, essays or poems. Click on the text in the box below, wherever it appears, and we will return you safely to the contents page. the stinging fly NEW WRITERS, NEW WRITING the stinging fly NEW WRITERS, NEW WRITING CONTENTS Danny Denton Editorial 4 Various Pandemic Notes from Contributors 5 FICTION Aude Enigma Of The Bend (translated by Cristy Stiles) 21 Robin Fuller Chinese Whispers 35 Niamh Campbell This Happy (an extract) 65 Yan Ge The Little House 74 Alex Bell Caledonia Whipping Boy 109 Philip Ó Ceallaigh My Life In The City 118 NONFICTION Ali Isaac The Word & The Kiss Are Born From The Same Body Part 47 Lisa McInerney Fantastic Babies: Notes on a K-pop Music Video 93 POETRY Celia Parra As I said I am (translated by Patrick Loughnane) 34 Dylan Brennan Desertion 64 Michael Dooley Eavesdropping 73 Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe Featured Poet – Two poems 88 Ruth Wiggins O 92 Katie O’Sullivan Sonnet to a SoftBoy™ (He Microwaved My Heart) 107 Jess McKinney The Good Kind of Green 108 Emily S. -

Alice Cooper 2011.Pdf

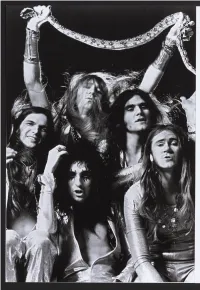

® • • • I ’ M - I N - T HE - MIDDLE-WIT HOUT ANT PLANS - I’M A BOY AND I’M-A MAN - I.’ M EIGHTEEN- - ® w Q < o ¡a 2 Ó z s * Tt > o ALICE M > z o g «< COOPER s [ BY BRAD T O L I N S K I ] y a n y standards, short years before, in 1967, Alice Cooper 1973 was an had been scorned as “the most hated exceptional year band” in Los Angeles. The group members for rock & roll. weirded out the locals by being the first Its twelve months hoys that weren’t transvestites to dress as saw the release girls, and their wildly dissonant, fuzzed- of such gems as out psychedelia sent even the most liberal Pink Floyd s The Dark Side of the Moon, hippies fleeing for the door. Any rational H H Led Zeppelin s Houses of the Holy, the human would have said they were 0 o W ho’s Quadrophenia, Stevie Wonders committing professional suicide, but z Innervisions, Elton Johns Goodbye Yellow the band members thought otherwise. Brick Road, and debuts from Lynyrd Who cared if a bunch o f Hollywood squares Skynyrd, Aerosmith, Queen, and the New thought they were gay? At least they Y ork D olls. were being noticed. But the most T H E BAND Every time they provocative and heard somebody audacious treasure G R A B B E D y e ll “faggot;” they of that banner year H EA D LIN ES AND swished more, and was Alice Coopers overnight they found £ o masterpiece, B illio n MADE WAVES fame as the group z w Dollar Babies, a it was hip to hate H m brilliant lampoon of American excess. -

The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson

The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson Stella and Phillip Lemarque Baba Rum International Publishing The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson © 2018 Stella and Phillip Lemarque All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in an form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors. Baba Rum International Publishing Los Angeles, California For more information or to contact the publisher visit bonjourneverland.com The essays in The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson are creative nonfiction. They are based on the authors’ true experiences but include dialog and fictional elements. Editorial and book design by Longhare Content & Editorial Services 2 The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson You are asking yourself, How does she know? Who is this—the cook! Yes, the cook. My name is Stella Lemarque. I created these dishes especially for Michael at Neverland, and here is my story. I grew up in Paris, the City of Lights—your typical Parisian girl. Yes, yes, in France we love our food. Food is a big part of the French culture. In my life, I have learned skills that have helped me cultivate a unique style of cooking. For a year, I worked at the side of one of the most famous chefs in the world, Roger Vergé, at his restaurant Le Moulin de Mougins. I was introduced to Provençȃle herbs, the cornerstone of French cuisine, which add myriad sparkles in your mouth. My time with Roger provided me with the knowledge to use the finest and freshest—and organic—ingredients to produce a plethora of pleasures during dining experiences. -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof.