Chase Utley, Ruben Tejada, and the Long History of the Mets Avenging Injustices by Eric Trager

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

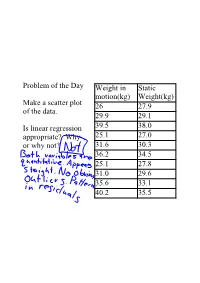

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Major Leagues Are Enjoying Great Wealth of Star

MAJOR LEAGUES ARE ENJOYING GREAT WEALTH OF STAR FIRST SACKERS : i f !( Major League Leaders at First Base l .422; Hornsby Hit .397 in the National REMARKABLE YEAR ^ AMERICAN. Ken Williams of Browns Is NATIONAL. Daubert and Are BATTlMi. Still Best in Hitting BATTING. Pipp Play-' PUy«,-. club. (1. AB. R.11. HB SB.PC. Player. Club. G. AB. R. H. I1R. SB. PC. Slsler. 8*. 1 182 SCO 124 233 7 47 .422 iit<*- Greatest Game of Cobb. r>et 726 493 89 192 4 111 .389 Home Huns. 105 372 52 !4rt 7 7 .376 Sneaker, Clev. 124 421 8.1 ir,« 11 8 .375 liar foot. St. L. 40 5i if 12 0 0 .375 I'll 11 Lives. JlHTneyt Det 71184 33 67 0 2 .364 Russell, Pitts.. 48 175 43 05 12 .4 .371 l.-llmunn, D«t. 118 474! #2 163 21 8 .338 Konseca, Cln. (14 220 39 79 2 3 .859 Hugh, N. Y 34 84 14 29 0 0 .347.! George Sisler of the Browne is the Stengel, N. V.. 77 226 42 80 6 5 .354 Woo<lati, 43 108 17 37 0 0 H43 121 445 90 157 13 6 .35.4 N. Y Ill 3?9 42 121 1 It .337 leading hitter of the American League 133 544 100 191 3 20 .351 IStfcant. .110 418 52 146 11 5 .349 \ an Glider, St. I.. 4<"» 63 15 28 2 0 .337 with a mark of .422. George has scored SISLER STANDS A I TOP 'i'obln, fit J 188 7.71 114 182 11 A .336 Y 71 190 34 66 1 1 .347 Ftagsloart, Det 87 8! 18 27 8 0 .833 the most runs. -

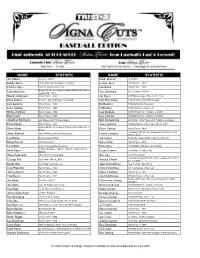

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Hip Arthroscopy

Evaluaon of Hip Pain: Athletes & Pre-arthri&c Hips John P Salvo, MD Sports Medicine Rothman Ins&tute Clinical Associate Professor, Orthopaedic Surgery Thomas Jefferson University Hospital Philadelphia, PA Hip Injuries Hip injuries on the rise around MLB A-Rod, Utley among stars to deal with surgery, recovery Todd Zolecki MLB.com 6/4/09 PHILADELPHIA -- Mike Lowell followed the Marlins' strength and condi&oning programs religiously.He worked out properly.He stretched properly.But late in the season he felt &ghtness in his right groin. Nobody could figure out why exactly because he had completed every program asked of him. But regardless of how hard he worked, the groin always &ghtened.Lowell, who played for the Marlins from 1999-2005 before he joined the Red Sox in 2006, learned later he had a torn labrum in his hip and required surgery.He is not alone. Hip injuries have been diagnosed more frequently in Major League Baseball. Lowell, who had successful surgery to repair the labrum Oct. 20, 2008, is one of several notable players who have had hip surgeries in recent months. Others include Yankees third baseman Alex Rodriguez, Phillies second baseman Chase Utley, Mets first baseman Carlos Delgado and Royals third baseman Alex Gordon. Phillies pitcher Breb Myers had successful hip surgery Thursday."You know, Tommy John got a surgery named aer him. I think they should name this one aer me," Lowell joked.But why all the hip injuries all of a sudden?"I think the main reason is improved recogni&on of the pathology," said orthopedic surgeon and hip specialist Bryan T. -

Heroes of the 5544 2008 Championship Jimmy Rollins Carlos Ruiz

N4 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2008 THE MORNING CALL FRIDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2008 N5 YO, PHILLY! WE DID IT! 1111 2288 2266 6 5 8 JIMMY ROLLINS • SS JAYSON WERTH • RF CHASE UTLEY • 2B RYAN HOWARD • 1B PAT BURRELL • LF SHANE VICTORINO • CF 1199 HEROES OF THE 5544 2008 CHAMPIONSHIP JIMMY ROLLINS CARLOS RUIZ In Game 161 of the regular season, he started an acrobatic 6-4-3 double play on Ryan After a dismal regular season at the plate, he was a lifeline for the Phillies in the postseason. In Zimmerman’s bases-loaded ground ball that looked like it was destined for center fi eld. The the fi rst three World Series games, he was 4-for-8 with four walks and a team-best three extra- twin-killing preserved the Phils’ 4-3 win over the Washington Nationals and gave the Phils their base hits (two doubles and a home run). In fi ve NLCS games and the opening three World Series second consecutive NL East Division title. Then after going 0-for-10 in the fi rst two games of games, hit .360. the World Series, was 5-for-9 and scored four runs in Games 3 and 4. JAMIE MOYER JAYSON WERTH Led the Phillies in regular-season wins (16). Although he got a no-decision, pitched well in GREG DOBBS • PH/3B Worked his way out of a platoon role and into the starting lineup just past the halfway part of Game 3 of the World Series, giving up just three runs, fi ve hits and one walk in 6 1/3 innings. -

The Guardian, April 11, 1979

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 4-11-1979 The Guardian, April 11, 1979 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1979). The Guardian, April 11, 1979. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. weather 'Consistency is a paste Jewel Rainy and windy today with a that only cheap men cherish' fvy high in the low 60* and a low /)} tflnight near 50. Cloudy tomorrow ' with a high expected in the low William Allen Whit WINDY 70». The Daily Guardian Offices, restaurants may crop up near WSU By MIKE MILLER planned last October are current- Guardian Special Writer ly under cons-ruction. Stan Swartz, from the Emro Last October, Fairborn Urban NtwiUasitt Land Company, said, "Since last Planner Hal Hunter said a memo- UOWSO&SF October we have installed the randum concerning the construc- OxxeQfficas sanitary sewer for the buildings. tion of new restaurants across the "The annexation and zoning street from Wright State was, has been approved for the res- "Mor or less in its final form." JbCh to.Klyc e taurants. The development of Si* mo:iths 'iter he says. "I don't Roattw 1-675 is holding up the construc- know when the construction will tion of the restaurants. -

F(Error) = Amusement

Academic Forum 33 (2015–16) March, Eleanor. “An Approach to Poetry: “Hombre pequeñito” by Alfonsina Storni”. Connections 3 (2009): 51-55. Moon, Chung-Hee. Trans. by Seong-Kon Kim and Alec Gordon. Woman on the Terrace. Buffalo, New York: White Pine Press, 2007. Peraza-Rugeley, Margarita. “The Art of Seen and Being Seen: the poems of Moon Chung- Hee”. Academic Forum 32 (2014-15): 36-43. Serrano Barquín, Carolina, et al. “Eros, Thánatos y Psique: una complicidad triática”. Ciencia ergo sum 17-3 (2010-2011): 327-332. Teitler, Nathalie. “Rethinking the Female Body: Alfonsina Storni and the Modernista Tradition”. Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America 79, (2002): 172—192. Biographical Sketch Dr. Margarita Peraza-Rugeley is an Assistant Professor of Spanish in the Department of English, Foreign Languages and Philosophy at Henderson State University. Her scholarly interests center on colonial Latin-American literature from New Spain, specifically the 17th century. Using the case of the Spanish colonies, she explores the birth of national identities in hybrid cultures. Another scholarly interest is the genre of Latin American colonialist narratives by modern-day female authors who situate their plots in the colonial period. In 2013, she published Llámenme «el mexicano»: Los almanaques y otras obras de Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (Peter Lang,). She also has published short stories. During the summer of 2013, she spent time in Seoul’s National University and, in summer 2014, in Kyungpook National University, both in South Korea. https://www.facebook.com/StringPoet/ The Best Players in New York Mets History Fred Worth, Ph.D. -

2020 Topps Archives Signatures Baseball Checklist

2020 Topps Archives Signatures Retired Baseball Player List - 110 Players Al Oliver David Cone Jim Rice Mike Schmidt Tim Lincecum Alex Rodriguez David Justice Jim Thome Mo Vaughn Tim Raines Andre Dawson David Ortiz Joe Mauer Moises Alou Tino Martinez Andres Galaragga David Wright Joe Pepitone Nolan Ryan Todd Helton Andruw Jones Dennis Eckersley John Smoltz Nomar Garciaparra Tom Glavine Andy Pettitte Dennis Martinez Johnny Bench Ozzie Smith Tony Perez Barry Larkin Don Mattingly Johnny Damon Randy Johnson Vern Law Barry Zito Dwight Gooden Jorge Posada Reggie Jackson Vladimir Guerrero Bartolo Colon Edgar Martinez Jose Canseco Rey Ordonez Wade Boggs Benito Santiago Eric Chavez Juan Gonzalez Rickey Henderson Will Clark Bernie Carbo Eric Davis Juan Marichal Roberto Alomar Bernie Williams Frank Thomas Ken Griffey Jr. Robin Yount Bert Blyleven Fred McGriff Kerry Wood Rod Carew Bob Gibson George Foster Lou Brock Roger Clemens Bronson Arroyo Gorman Thomas Luis Gonzalez Rollie Fingers Cal Ripken Jr. Hank Aaron Luis Tiant Rondell White Carl Yazstremski Hideki Matsui Magglio Ordonez Ruben Sierra Carlton Fisk Ichiro Manny Sanguillen Ryan Howard CC Sabathia Ivan Rodriguez Mariano Rivera Ryne Sandberg Cecil Fielder Jason Varitek Mark Grace Sandy Alomar Jr. Chipper Jones Jay Buhner Mark McGwire Sandy Koufax Cliff Floyd Jeff Bagwell Mark Teixeira Sean Casey Dale Murphy Jeff Cirillo Maury Willis Shawn Green Darryl Strawberry Jerry Remy Miguel Tejeda Steve Carlton Dave Stewart Jim Abbott Mike Mussina Steve Rogers 2020 Topps Archives Signatures Baseball Player List - 110 Players. -

Cards' Forseh Wins 100Th

Cards' Forseh wins 100th (2-6- ) out United Press International SAN FRANCISCO 4, CHICAGO 3 Seaver struck six and one seven innings to win at Chicago Chili Davis hit a two-ru-n walked in ST. LOUIS George Hendrick National homer in the first inning and his first, game since May 4. Tom drove in three runs with a homer and Milt May and Tom O'Malley each Hume pitched thefinalteojnnings. to Bob a single Friday night help League drove in a run in the third to give the A spectacular diving catch by left Forseh gain his 100th career victory San Francisco Giants a victory over Mike Vail in sixth inning, Cardinals to fielder the and lead St. Louis a 3, the the Chicago Cubs. when Cincinnati led 4-- cut off two 5-- 2 triumph over the Los Angeles Los Angeles bunched a single by The loss was Chicago's fifth in a Reds then Garvey, possible runs. The erupted Dodgers. Steve a double by Dusty row, its longest losing streak of the for four runs with two out in the The victory was the Cardinals' Baker and a single by Pedro Guerre- season. sixth. 10 games. two eighth in the last ro for its runs in the fourth. The Fred Breining (3--1) relieved start- Dodgers 2--0 Dodgers' only was The took a lead in the other hit a double er Mike Chris in the first inning and SAN DIEGO 5, PITTSBURGH 4 at fourth but St. Louis tied it in the fifth by Garvey in the sixth. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Bowling Green Is a 1980S

BGSU ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT . m f. 1 IT ^K|| UP MM #1 ■# • , \ < . - #** | f ■ ' Bowling Green N * % Is A 1980s B^ ' / (..JS UP, I oUCCeSS £)TOry 1988 MAC Basketball Champions 1988 MAC Softball Champions When, in the year 2000, historians look BG women to four CC titles in eight back upon 85 years of intercollegiate years. Now, he's out working his magic athletics at Bowling Green State Univer- on both the Falcon men and women. sity, they'll stop and take a second look FOOTBALL - Bowling Green is the at the 1980s, Bowling Green sports MAC's winningest team of the 1980s teams of the 80s have achieved a level with a first- or second-place finish the of success matched by few. last six years. The Falcons have won two In all. Bowling Green teams have won MAC titles and made two trips to the 21 conference titles the last eight years, California Bowl since 1980. BG also 17 in the Mid-American Conference holds the MAC single-game atten- and four in the Central Collegiate dance record of 33,527 at Doyt Perry Hockey Association. Sixteen teams Field. Coach Moe Ankney has guided have gone on to post-season play in the Falcons to two-straight second- the NCAA, NIT and California Bowl. place finishes. Taking the next step to Bowling Green student-athletes the top is the goal for 1988. distinguished themselves in numerous GOLF — Coach Greg Nye's men's and ways in 1987-88. MAC champions were women's golf teams play on some of crowned in women's basketball and the most challenging courses in the softball. -

You Are the Body of Christ Preacher: Rev

You are the Body of Christ Preacher: Rev. Lauren Lorincz Date: January 24, 2016 13:29 “You are the Body of Christ” Pilgrim Church UCC, January 24, 2016, (1 Corinthians 12:12-31a) Third Sunday after Epiphany Let’s go back to Game 6 of the 1986 World Series at Shea Stadium in Queens. The Mets are trailing the Red Sox 5-4 and are one out from finishing an amazing season with a disappointing loss. Mookie Wilson’s at the plate and Red Sox pitcher Bob Stanley throws a wild pitch to bring Kevin Mitchell home. All of a sudden, the Mets and the Sox are tied in the bottom of the 10th inning—and then comes the infamous moment. Wilson has a full count and hits a grounder up the first-base line. Bill Buckner, the veteran first baseman, hobbles to field this ground ball and reaches down too late. The ball bounces between his legs and rolls right behind him. Ray Knight rounds third base for the Mets and heads home—leaping with joy. The Mets tie the series at three games apiece and go on to win the 1986 World Series. The scapegoat for Boston sports fans became Bill Buckner. Some of you may be having flashbacks of anger, disappointment, heart palpitations, you name it just by hearing his name. And I understand—Cleveland fans have The Drive, The Fumble, and Red Right 88. What’s fascinating is when Red Sox fans recall the missed opportunities of the past, people don’t seem to speak as much about Bob Stanley’s wild pitch which brought in the runner on third before Mookie Wilson even hit that grounder to Bill Buckner.