Civic Center and Cultural Center: the Grouping of Public Buildings In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cleveland, Ohio

THE DEXTER | Ohio City | Cleveland, Ohio SIZE AVE 8,250 square feet 42 2 DETROIT Cu ya W 29 hoga Riv 6 CHURCH AVE W 28 T H er LOCATION ST TH ST CARTER RD Ohio City, Ohio ON AVE W. 28th Street & Franklin Blvd. CLINT W 25 TH VD ST TRAFFIC COUNTS FRANKLIN BL W 32 W 38 Franklin Blvd. - 4,231 OHIO CITY ND W 28 TON RD TH US-42/W. 25th Street - 14,860 ST ST FUL E TH Detroit Avenue - 16,764 AV ST US-6/Cleveland Memorial Shoreway - 42,725 BRIDGE LORAIN AVE KEY DEMOGRAPHICS TRADE AREA POPULATION The Dexter is a new mixed-use project Current Estimated Population 13,993 nestled in the heart of Cleveland’s Ohio City neighborhood. The project offers 8,250 LEASING CONTACT INCOME square feet of prime retail and restaurant Average Household Income $67,247 space available on the ground floor, 115 Brent Myers luxury residential apartments on the upper 614.744.2208 DIRECT MEDIAN AGE 35 years four floors and onsite parking. Retailers will 614.228.5331 OFFICE have exceptional visibility and frontage on DAYTIME DEMOGRAPHICS [email protected] the soon-to-be reinstated Franklin Circle. Number of Employees 290,668 Outdoor patio space is available. Total Daytime Population 381,861 The site offers connectivity to the W. 25th Street and Hingetown/Detroit Avenue commercial corridors and is conveniently located across from Lutheran Hospital/Cleveland Clinic with 1,300 employees. The Dexter will also be connected to Irishtown Bend, a collaborative effort to create a new 17-acre urban park with active recreational areas as well as community-oriented areas devoted to history, ecology and culture. -

Districts 7, 8, and 10 Detroit Historical Society March 7, 2015

Michigan History Day Districts 7, 8, and 10 Detroit Historical Society March 7, 2015 www.hsmichigan.org/mhd [email protected] CONTEST SCHEDULE 9:00-9:50 a.m. Registration & Set up 9:00- 9:50 a.m. Judges’ Orientation 9:50 a.m. Exhibit Room Closes 10:00 a.m. Opening Ceremonies - Booth Auditorium 10:20 a.m. Judging Begins Documentaries Booth Auditorium, Lower Level Exhibits Wrigley Hall, Lower Level Historical Papers Volunteer Lounge, 1st Floor Performances Discovery Room, Lower Level Web Sites DeRoy Conference Room, 1st Floor and Wrigley Hall, Lower Level 12:30-2:00 p.m. Lunch Break (see options on page 3) 12:30-2:00 p.m. Exhibit Room open to the public 2:00 p.m. Awards and Closing Ceremonies – Booth Auditorium We are delighted that you are with us and hope you will enjoy your day. If you have any questions, please inquire at the Registration Table or ask one of the Michigan History Day staff. Financial Sponsors of Michigan History Day The Historical Society of Michigan would like to thank the following organizations for providing generous financial support to operate Michigan History Day: The Cook Charitable Foundation The Richard and Helen DeVos Foundation 2 IMPORTANT INFORMATION! STUDENTS: Please be prepared 15 minutes before the time shown on the schedule. You are responsible for the placement and removal of all props and equipment used in your presentation. Students with exhibits should leave them up until after the award ceremony at 2:00 pm, so that the judges may have adequate time to evaluate them. -

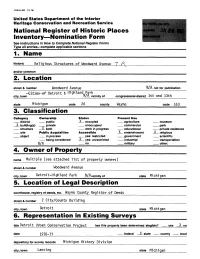

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name_________________ —————————historic Religious Structures of Woodward Avenue Ti f\3,5- and/or common_____________________________________ 2. Location street & number N/A_ not for publication Detroit & Highland Park city, town N£A_ vicinityvi of congressional district 1st and 13th, state Michigan code 26 county Wayne code 163 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public _X _ occupied agriculture museum 1private unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible X entertainment _X _ religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple (see attached list of property owners) street & number Woodward Avenue city,town Detroit-Highland Park .N/Avicinity of state Michigan 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Wayne County Register of Deeds street & number 2 City/County Building city, town Detroit state Michigan 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ title Detroit Urban Conservation Project has this property been determined elegible? __yes X no date 1976-77 federal _X_ state county local -

View the June Summer Fun Guide

18-19 summerfun_Layout 1 5/16/14 2:58 PM Page 18 Cool off this summer at the area’s best w Crocker Park Splash Zone Photo courtesy of Lisa Schwan When summer in Northeast Ohio arrives, the steamy temperatures often leave families in search of ways to cool off. Whether you’re seeking a full-day trip bles and separate small children’s area. or a quick dip, fast thrills to relaxing Water Works Family Fun Center chills, there are some great water- boasts a variety of slides, from larger themed activities — that are affordable enclosed tube and open body slides to a or free — close to home. While we can’t lazy river, waterfalls and geysers. cover them all, read on for some high- Looking for some free water fun for lights to add to your family’s summer the kids? Edgewater Park itinerary. Don’t overlook local splash pads, Photos courtesy of Cleveland Metroparks including one at Crocker Park in West- Make a Splash lake. Splash Pad, presented by Lake Get all the thrills of a waterpark without Ridge Academy, is open daily and offers Watersports, Fast and Slow the long drive and high admission price kids an opportunity to cool down while Whether you’re more of the spectating by visiting Pioneer Waterland & Dry Fun burning off some energy. As an added type or the kind who likes to jump in on Park in Chardon, Clay’s Park in North bonus, most evenings, the pad trans- the action, watersport opportunities Lawrence or Water Works Family Fun forms into a light show. -

The Cultural Learning Process : Diffusion Versus Evolution

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1979 The cultural learning process : diffusion versus evolution. Paul Shao University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Shao, Paul, "The cultural learning process : diffusion versus evolution." (1979). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3539. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3539 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULTURAL LEARNING PROCESS; DIFFUSION VERSUS EVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented By PAUL PONG WAH SHAO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February 1979 Education Paul Shao 1978 © All Rights Reserved THE CULTURAL LEARNING PROCESS: DIFFUSION VERSUS EVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented By PAUL PONG WAH SHAO Approved as to style and content by: ABSTRACT The Cultural Learning Process: Diffusion Versus Evolution February, 1979 Paul Shao, B.A., China Art College M.F.A., University of Massachusetts Ed. D., University of Massachusetts Directed By: Professor Daniel C. Jordan Purpose of the Study This study attempts to shed -

CMA Landscape Master Plan

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART LANDSCAPE MASTER PLAN DECEMBER 2018 LANDSCAPE MASTER PLAN The rehabilitation of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s grounds requires the creativity, collaboration, and commitment of many talents, with contributions from the design team, project stakeholders, and the grounds’ existing and intended users. Throughout the planning process, all have agreed, without question, that the Fine Arts Garden is at once a work of landscape art, a treasured Cleveland landmark, and an indispensable community asset. But the landscape is also a complex organism—one that requires the balance of public use with consistency and harmony of expression. We also understand that a successful modern public space must provide more than mere ceremonial or psychological benefits. To satisfy the CMA’s strategic planning goals and to fulfill the expectations of contemporary users, the museum grounds should also accommodate as varied a mix of activities as possible. We see our charge as remaining faithful to the spirit of the gardens’ original aesthetic intentions while simultaneously magnifying the rehabilitation, ecological health, activation, and accessibility of the grounds, together with critical comprehensive maintenance. This plan is intended to be both practical and aspirational, a great forward thrust for the benefit of all the people forever. 0' 50' 100' 200' 2 The Cleveland Museum of Art Landscape Master Plan 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CMA Landscape Master Plan Committee Consultants William Griswold Director and President Sasaki Heather Lemonedes -

Tourism and Cultural Identity: the Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center

Athens Journal of Tourism - Volume 1, Issue 2 – Pages 101-120 Tourism and Cultural Identity: The Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center By Jeffery M. Caneen Since Boorstein (1964) the relationship between tourism and culture has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. This paper reviews the debate and contrasts it with the anthropological focus on cultural invention and identity. A model is presented to illustrate the relationship between the image of authenticity perceived by tourists and the cultural identity felt by indigenous hosts. A case study of the Polynesian Cultural Center in Laie, Hawaii, USA exemplifies the model’s application. This paper concludes that authenticity is too vague and contentious a concept to usefully guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. It recommends, rather that preservation and enhancement of identity should be their focus. Keywords: culture, authenticity, identity, Pacific, tourism Introduction The aim of this paper is to propose a new conceptual framework for both understanding and managing the impact of tourism on indigenous host culture. In seminal works on tourism and culture the relationship between the two has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. But as Prideaux, et. al. have noted: “authenticity is an elusive concept that lacks a set of central identifying criteria, lacks a standard definition, varies in meaning from place to place, and has varying levels of acceptance by groups within society” (2008, p. 6). While debating the metaphysics of authenticity may have merit, it does little to guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. -

Noel Night Schedule 2017

Noel Night Schedule 2017 PERFORMANCES TIME PERFORMER DESCRIPTION VENUE 6:00pm William Underwood Flute 3980 Second 7:00pm Bev Love 3980 Second 8:00pm Stacye' J 3980 Second 5:30pm Bella Prasatek Jazz 71 Garfield 6:30pm Bella Prasatek Jazz 71 Garfield 7:30pm Bella Prasatek Jazz 71 Garfield Throughout the evening Saxaphone Saxaphone 71 Garfield - LTGraphics + Art City 5:45pm LaShaun Phoenix Moore Carolers Alley Taco 5:15pm LaShaun Phoenix Moore Carolers Avalon International Breads 4:30pm Bethel A.M.E. Church Praise Chorale Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 5:00pm Aaron "BraveSoutl" Parrott Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 5:00pm Bethel A.M.E. Church Kids Jump 4 Jesus Dance Ministry Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 5:00pm Burton International School Dance Company Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 5:45pm Messiah Baptist Church Men of Praise Choir Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 6:15pm LaShelle's School of Dance featuring LSO Dance Company Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 6:30pm Gospel Temple Baptist Church Choir Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 7:00pm Michael Mindingall's Communion Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 7:30pm Derrick Milan & The Crew Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 8:00pm Spain Middle School Dance Company Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 8:00pm East English Village Preparatory Academy Dance Team Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 8:00pm Duke Ellington Dance Ensemble Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary 8:45pm St. Paul A.M.E. Zion District Choir Bethel A.M.E. Church - Sanctuary Throughout the evening Christmas Karaoke Bikram Yoga Midtown -

The Culture of Power Adapted from Uprooting Racism: How White People Can Work for Racial Justice

The Culture of Power adapted from Uprooting Racism: How White People Can Work for Racial Justice by Paul Kivel IF YOU ARE A WOMAN and you have ever walked into a men’s meeting, or a person of color and have walked into a white organization, or a child who walked into the principal’s office, or a Jew or Muslim who entered a Christian space, then you know what it is like to walk into a culture of power that is not your own. You may feel insecure, unsafe, disrespected, unseen or marginalized. You know you have to tread carefully. Whenever one group of people accumulates more power than another group, the more powerful group creates an environment that places its members at the cultural center and other groups at the margins. People in the more powerful group (the “in-group”) are accepted as the norm, so if you are in that group it can be very hard for you to see the benefits you receive. Since I’m male and I live in a culture in which men have more social, political, and economic power than women, I often don’t notice that women are treated differently than I am. I’m inside a male culture of power. I expect to be treated with respect, to be listened to, and to have my opinions valued. I expect to be welcomed. I expect to see people like me in positions of authority. I expect to find books and newspapers that are written by people like me, that reflect my perspective, and that show me in central roles. -

Educating Graduate Teaching Assistants in At-Risk Pedagogy Kristen P

Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal Volume 41 Combined Volume 41/42 (2014/2015) Article 3 January 2014 Communication in Action: Educating Graduate Teaching Assistants in At-Risk Pedagogy Kristen P. Treinen Minnesota State University - Mankato, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/ctamj Part of the Communication Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Treinen, K. (2014/2015). Communication in Action: Educating Graduate Teaching Assistants in At-Risk Pedagogy. Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal, 41/42, 6-28. This Teacher's Workbook is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Treinen: Communication in Action: Educating Graduate Teaching Assistants i 6 CTAMJ 2014/2015 TEACHERS’ WORKBOOK FEATURED MANUSCRIPT Communication in Action: Educating Graduate Teaching Assistants in At-Risk Pedagogy Kristen P. Treinen, PhD Associate Professor of Communication Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato [email protected] Abstract I begin this paper with a glimpse into the literature concerning at-risk and antiracist theory in order to understand the connections between the two bodies of literature. Next, by combining two bodies of literature, I argue for the implementation of a pedagogy of hope, culturally relevant teaching, and empowerment for students in the classroom. Finally, I outline a course for graduate teaching assistants that explores the utility of a pedagogy of hope, culturally relevant teaching, and empowerment for students in the communication classroom. -

Peacock Room to Open 2Nd Detroit Location

2B WWW.FREEP.COM THURSDAY, AUG. 3, 2017Detroit Free Press - 08/03/2017 Copy Reduced to 86% from original to fit letter page Page : B002 BUSINESS w Headlines Peacock Room to open 2nd Detroit location AUTOS Ferrari considers opular Detroit women’s a utility vehicle clothing retailer the PPeacock Room is to open a second store in Fisher Ferrari’s chief exec- Building this fall. utive told investors About three times bigger Wednesday that the luxu- than the existing Peacock GEORGEA KOVANIS ry sports car maker will Room — which measures ON STYLE look at building a cross- about 1,100 square feet and is over utility vehicle, but in the Park Shelton in Mid- promised any model it town — the new Fisher Build- ber, she plans to open Yama. produces would be ing store will serve as the Located in the Fisher Build- unique and not compro- retailer’s flagship location. ing, it will specialize in wom- mise the brand’s exclu- In addition to more of the en’s clothing with a modern sivity. vintage-inspired dresses edge. CEO Sergio Mar- (think Hollywood glamour “There’s a backlash against chionne has in the past from the 1920s-1950s) and fun the big box experience,” said colorfully disavowed accessories for which the Lutz, who counts incredible Ferrari entering the Peacock Room has become personal service as some- utility vehicle segment. known, the flagship store also thing that differentiates her During the 90-minute will have a mini bridal bou- stores from chains and also investor call, analysts, tique for nontraditional from online shopping. -

The Wayne Framework | Appendix (Pdf)

1 2 DR THE WAYNE FRAMEWORK 2019 APPENDIX 3 4 CONTENTS COMAP SURVEY 7 COST ESTIMATE + FINANCIAL MODEL 19 Building financial model 21 Landscape financial model 33 TRANSPORTATION 39 Introduction 40 Parking 42 Traffic 54 Non-auto facilities 62 Crash & safety 73 Street intervention ideas 77 Campus shuttle 83 BUILDING ASSESSMENT 91 Scope and method of building assessment 92 Summary of building assessment 94 Assessment for selected buildings 102 HISTORIC RESOURCES 153 Campus historic resources map 154 Building treatment approach 155 Assessment for selected buildings 156 5 COMAP SURVEY 791 survey responses Years at WSU (student) Years at WSU (faculty and staff) Lived distance Collaboration (student) Collaboration (faculty) 8 Responses by school/college Faculty Student 9755 icons placed Thumb down Thumb up In-between COMAP SURVEY 9 CAMPUS ZONE WHERE IS THE HEART OF CAMPUS? Gullen & Williams Mall -”Crossroads of main paths, interactions between both commuters and people who live in the residence halls.” Fountain Court -”This is where the most daily activity on campus is. During winter I’d say it moves inside to the Student Center.” Student Center -” The Student Center is a place where many students love to congregate. It is a place for commuters and for on-campus students alike. They study, hangout, socialize, eat, and play all kinds of games here. I only wish there were more unique places like it .” 10 WHERE ARE YOUR FAVORITE AND LEAST FAVORITE CLASSROOMS? State Hall COMAP SURVEY 11 WHERE DO YOU LIVE? WHERE DO YOU EAT? The Towers Residential Suites -”The food is good but it is a very far walk Student Center -”I wish there were more food options in the from where many of us live, especially in student center.