Soil Erosion and Acidity Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Degradation Neutrality

Land Degradation Neutrality: implications and opportunities for conservation Nature Based Solutions to Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought 2nd Edition, November 2015 IUCN Global Drylands Initiative Land Degradation Neutrality: implications and opportunities for conservation Nature Based Solutions to Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought 2nd Edition, November 2015 With contributions from Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA, CEC1 1 Contributors: Jonathan Davies, Masumi Gudka, Peter Laban, Graciela Metternicht, Sasha Alexander, Ian Hannam, Leigh Welling, Liette Vasseur, Jackie Siles, Lorena Aguilar, Lene Poulsen, Mike Jones, Louisa Nakanuku-Diggs, Julianne Zeidler, Frits Hesselink Copyright: ©2015 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA and CEC. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN and CEM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN,Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA and CEC. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage -

Soil Acidification

viti-notes [grapevine nutrition] Soil acidifi cation Viti-note Summary: Characteristics of acidic soils • Soil pH Calcium and magnesium are displaced • Soil acidifi cation in by aluminium (Al3+) and hydrogen (H+) vineyards and are leached out of the soil. Acidic soils below pH 6 often have reduced • Characteristics of acidic populations of micro-organisms. As soils microbial activity decreases, nitrogen • Acidifying fertilisers availability to plants also decreases. • Effect of soil pH on Sulfur availability to plants also depends rate of breakdown of on microbial activity so in acidic soils, ammonium to nitrate where microbial activity is reduced, Figure 1. Effect of soil pH on availability of minerals sulfur can become unavailable. (Sulfur • Management of defi ciency is not usually a problem for acidifi cation Soil pH vineyards as adequate sulfur can usually • Correction of soil pH All plants and soil micro-organisms have be accessed from sulfur applied as foliar with lime preferences for soil within certain pH fungicides). ranges, usually neutral to moderately • Strategies for mature • Phosphorus availability is reduced at acid or alkaline. Soil pH most suitable vines low pH because it forms insoluble for grapevines is between 5.5 and 8.5. phosphate compounds with In this range, roots can acquire nutrients aluminium, iron and manganese. from the soil and grow to their potential. As soils become more acid or alkaline, • Molybdenum is seldom defi cient in grapevines become less productive. It is neutral to alkaline soils but can form important to understand the impacts of insoluble compounds in acid soils. soil pH in managing grapevine nutrition, • In strongly acidic soil (pH <5), because the mobility and availability of aluminium may become freely nutrients is infl uenced by pH (Figure 1). -

Global Environmental Issues and Its Remedies

International Journal of Sustainable Energy and Environment Vol. 1, No. 8, September 2013, PP: 120 - 126, ISSN: 2327- 0330 (Online) Available online at www.ijsee.com Research article Global Environmental Issues and its Remedies Dr. MD. Zulfequar Ahmad Khan* Address Present. Permanent Address for Correspondence *Dr. Md Zulfequar Ahmad Khan 21-B, Lane No 3, Associate Professor Jamia Nagar, Zakir Nagar, Department of Geography & Environmental Studies New Delhi-110025 Arba Minch University INDIA Arba Minch, Ethiopia. Mobile No.: +919718502867 Mobile No: +251 923934234 E-mail: [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract To the surprise of many out-spoken environmentalists, it, in fact, turns out mankind and technology actually aren’t the only significant causes of global environmental problems. However, before we start to get too comfortable and confidently assume that we as human beings are officially “off the hook,” the fact remains that several “man-made” causes play a significant role in our current, global problems trend. Many human actions affect what people value. One way in which the actions that cause global change are different from most of these is that the effects take decades to centuries to be realized. This fact causes many concerned people to consider taking action now to protect the values of those who might be affected by global environmental change in years to come. But because of uncertainty about how global environmental systems work, and because the people affected will probably live in circumstances very much different from those of today and may have different values, it is hard to know how present-day actions will affect them. -

Chapter 4: Land Degradation

Final Government Distribution Chapter 4: IPCC SRCCL 1 Chapter 4: Land Degradation 2 3 Coordinating Lead Authors: Lennart Olsson (Sweden), Humberto Barbosa (Brazil) 4 Lead Authors: Suruchi Bhadwal (India), Annette Cowie (Australia), Kenel Delusca (Haiti), Dulce 5 Flores-Renteria (Mexico), Kathleen Hermans (Germany), Esteban Jobbagy (Argentina), Werner Kurz 6 (Canada), Diqiang Li (China), Denis Jean Sonwa (Cameroon), Lindsay Stringer (United Kingdom) 7 Contributing Authors: Timothy Crews (The United States of America), Martin Dallimer (United 8 Kingdom), Joris Eekhout (The Netherlands), Karlheinz Erb (Italy), Eamon Haughey (Ireland), 9 Richard Houghton (The United States of America), Muhammad Mohsin Iqbal (Pakistan), Francis X. 10 Johnson (The United States of America), Woo-Kyun Lee (The Republic of Korea), John Morton 11 (United Kingdom), Felipe Garcia Oliva (Mexico), Jan Petzold (Germany), Mohammad Rahimi (Iran), 12 Florence Renou-Wilson (Ireland), Anna Tengberg (Sweden), Louis Verchot (Colombia/The United 13 States of America), Katharine Vincent (South Africa) 14 Review Editors: José Manuel Moreno Rodriguez (Spain), Carolina Vera (Argentina) 15 Chapter Scientist: Aliyu Salisu Barau (Nigeria) 16 Date of Draft: 07/08/2019 17 Subject to Copy-editing 4-1 Total pages: 186 Final Government Distribution Chapter 4: IPCC SRCCL 1 2 Table of Contents 3 Chapter 4: Land Degradation ......................................................................................................... 4-1 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

Soil Acidification

Soil Acidification and Pesticide Management pH 5.1 November 14, 2018 MSU Pesticide Education Program pH 3.8 Image courtesy Rick Engel Clain Jones [email protected] 406-994-6076 MSU Soil Fertility Extension What happened here? Image by Sherrilyn Phelps, Sask Pulse Growers Objectives Specifically, I will: 1. Show prevalence of acidification in Montana (similar issue in WA, OR, ID, ND, SD, CO, SK and AB) 2. Review acidification’s cause and contributing factors 3. Show low soil pH impact on crops 4. Explain how this relates to efficacy and persistence of pesticides (specifically herbicides) 5. Discuss steps to prevent or minimize acidification Prevalence: MT counties with at least one field with pH < 5.5 Symbol is not on location of field(s) 40% of 20 random locations in Chouteau County have pH < 5.5. Natural reasons for low soil pH . Soils with low buffering capacity (low soil organic matter, coarse texture, granitic rather than calcareous) . Historical forest vegetation soils < pH than historical grassland . Regions with high precipitation • leaching of nitrate and base cations • higher yields, receive more N fertilizer • often can support continuous cropping and N each yr Agronomic reasons for low soil pH • Nitrification of ammonium-based N fertilizer above plant needs - + ammonium or urea fertilizer + air + H2O→ nitrate (NO3 ) + acid (H ) • Nitrate leaching – less nitrate uptake, less root release of basic - - anions (OH and HCO3 ) to maintain charge balance • Crop residue removal of Ca, Mg, K (‘base’ cations) • No-till concentrates acidity where N fertilizer applied • Legumes acidify their rooting zone through N-fixation. Perennial legumes (e.g., alfalfa) more than annuals (e.g., pea), but much less than fertilization of wheat. -

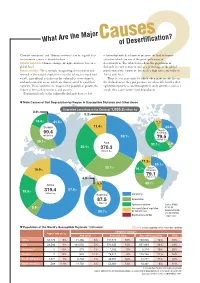

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Land Degradation

SPM4 Land degradation Coordinating Lead Authors: Lennart Olsson (Sweden), Humberto Barbosa (Brazil) Lead Authors: Suruchi Bhadwal (India), Annette Cowie (Australia), Kenel Delusca (Haiti), Dulce Flores-Renteria (Mexico), Kathleen Hermans (Germany), Esteban Jobbagy (Argentina), Werner Kurz (Canada), Diqiang Li (China), Denis Jean Sonwa (Cameroon), Lindsay Stringer (United Kingdom) Contributing Authors: Timothy Crews (The United States of America), Martin Dallimer (United Kingdom), Joris Eekhout (The Netherlands), Karlheinz Erb (Italy), Eamon Haughey (Ireland), Richard Houghton (The United States of America), Muhammad Mohsin Iqbal (Pakistan), Francis X. Johnson (The United States of America), Woo-Kyun Lee (The Republic of Korea), John Morton (United Kingdom), Felipe Garcia Oliva (Mexico), Jan Petzold (Germany), Mohammad Rahimi (Iran), Florence Renou-Wilson (Ireland), Anna Tengberg (Sweden), Louis Verchot (Colombia/ The United States of America), Katharine Vincent (South Africa) Review Editors: José Manuel Moreno (Spain), Carolina Vera (Argentina) Chapter Scientist: Aliyu Salisu Barau (Nigeria) This chapter should be cited as: Olsson, L., H. Barbosa, S. Bhadwal, A. Cowie, K. Delusca, D. Flores-Renteria, K. Hermans, E. Jobbagy, W. Kurz, D. Li, D.J. Sonwa, L. Stringer, 2019: Land Degradation. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)]. In press. -

Nitrogen Deposition Contributes to Soil Acidification in Tropical Ecosystems

Global Change Biology Global Change Biology (2014), doi: 10.1111/gcb.12665 Nitrogen deposition contributes to soil acidification in tropical ecosystems XIANKAI LU1 , QINGGONG MAO1,2,FRANKS.GILLIAM3 ,YIQILUO4 and JIANGMING MO 1 1Key Laboratory of Vegetation Restoration and Management of Degraded Ecosystems, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China, 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China, 3Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755-2510, USA, 4Department of Microbiology and Plant Biology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA Abstract Elevated anthropogenic nitrogen (N) deposition has greatly altered terrestrial ecosystem functioning, threatening eco- system health via acidification and eutrophication in temperate and boreal forests across the northern hemisphere. However, response of forest soil acidification to N deposition has been less studied in humid tropics compared to other forest types. This study was designed to explore impacts of long-term N deposition on soil acidification pro- cesses in tropical forests. We have established a long-term N-deposition experiment in an N-rich lowland tropical for- À1 À1 est of Southern China since 2002 with N addition as NH4NO3 of 0, 50, 100 and 150 kg N ha yr . We measured soil acidification status and element leaching in soil drainage solution after 6-year N addition. Results showed that our study site has been experiencing serious soil acidification and was quite acid-sensitive showing high acidification < < (pH(H2O) 4.0), negative water-extracted acid neutralizing capacity (ANC) and low base saturation (BS, 8%) through- out soil profiles. Long-term N addition significantly accelerated soil acidification, leading to depleted base cations and decreased BS, and further lowered ANC. -

Assessing Climate Change's Contribution to Global Catastrophic

Assessing Climate Change’s Contribution to Global Catastrophic Risk Simon Beard,1,2 Lauren Holt,1 Shahar Avin,1 Asaf Tzachor,1 Luke Kemp,1,3 Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh,1,4 Phil Torres, and Haydn Belfield1 5 A growing number of people and organizations have claimed climate change is an imminent threat to human civilization and survival but there is currently no way to verify such claims. This paper considers what is already known about this risk and describes new ways of assessing it. First, it reviews existing assessments of climate change’s contribution to global catastrophic risk and their limitations. It then introduces new conceptual and evaluative tools, being developed by scholars of global catastrophic risk that could help to overcome these limitations. These connect global catastrophic risk to planetary boundary concepts, classify its key features, and place global catastrophes in a broader policy context. While not yet constituting a comprehensive risk assessment; applying these tools can yield new insights and suggest plausible models of how climate change could cause a global catastrophe. Climate Change; Global Catastrophic Risk; Planetary Boundaries; Food Security; Conflict “Understanding the long-term consequences of nuclear war is not a problem amenable to experimental verification – at least not more than once" Carl Sagan (1983) With these words, Carl Sagan opened one of the most influential papers ever written on the possibility of a global catastrophe. “Nuclear war and climatic catastrophe: Some policy implications” set out a clear and credible mechanism by which nuclear war might lead to human extinction or global civilization collapse by triggering a nuclear winter. -

Lowering Soil Ph for Horticulture Crops

PURDUE EXTENSION HO-241-W Commercial Greenhouse and Nursery Production Lowering Soil pH for Horticulture Crops Purdue Horticulture and Michael V. Mickelbart and Kelly M. Stanton, Landscape Architecture Purdue Horticulture and Landscape Architecture www.ag.purdue.edu/HLA Steve Hawkins and James Camberato, Purdue Agronomy Purdue Agronomy www.ag.purdue.edu/AGRY The pH scale measures the acidity or alkalinity of a solution. The scale extends from 0 (a very strong acid) to 14 (a very strong base or highly alkaline). The middle of the scale, 7, is neutral, neither acidic nor basic. Soil pH is important because it affects the availability of nutrients in the rooting zone. This publication explains when lowering soil pH is important for commercial producers and recommends practices to safely and effectively lower soil pH. For more about soil pH, see Purdue Extension publication HO-240-W, Commercial Greenhouse and Nursery Production: Soil pH (available from the Purdue Extension Education Store, www. the-education-store.com). When it comes to soil pH, an accurate diagnosis is essential. Before making any changes, test your soil pH. Purdue Extension provides a list of commercial soil testing labs at: www.ag.purdue.edu/agry/extension/Pages/soil-testing-labs.aspx Why Lower Soil pH? Some plants (such as blueberries or azaleas) are adapted to grow in acid soils — even as low as pH 4.5. If you are trying to grow them you may want a soil pH less than 6, but remember that even acid-loving plants have their limits. Table 1. Effects of soil amendments on pH. -

Chemical and Biochemical Properties of Soils Developed from Different Lithologies in Northwestern Spain (Galicia)

Article Chemical and Biochemical Properties of Soils Developed from Different Lithologies in Northwestern Spain (Galicia) Valeria Cardelli 1,*, Stefania Cocco 1, Alberto Agnelli 2, Serenella Nardi 3, Diego Pizzeghello 3, Maria J. Fernández‐Sanjurjo 4 and Giuseppe Corti 1 1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, 60131, Italy; [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Perugia, 06121, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Agronomy, Food, Natural Resources, Animals and the Environment, Università degli Studi di Padova, Legnaro, 35020, Italy; [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (D.P.) 4 Department of Soil and Agronomic Chemistry, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Lugo, 27001, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39‐338‐599‐6867 Academic Editors: Adele Muscolo and Miroslava Mitrovic Received: 15 March 2017; Accepted: 19 April 2017; Published: 22 April 2017 Abstract: Physical and chemical soil properties are generally correlated with the parent material, as its composition may influence the pedogenetic processes, the content of nutrients, and the element biocycling. This research studied the chemical and biochemical properties of the A horizon from soils developed on different rocks like amphibolite, serpentinite, phyllite, and granite under a relatively similar climatic regime from Galicia (northwest Spain). In particular, the effect of the parent material on soil evolution, organic carbon sequestration, and the hormone‐like activity of humic and fulvic acids were tested. Results indicated that all the soils were scarcely fertile because of low concentrations of available P, exchangeable Ca (except for the soils on serpentinite and phyllite), and exchangeable K, but sequestered relevant quantities of organic carbon.