FINDING BETTER SORTING NETWORKS a Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Sorting Algorithms

Unit 7 Sorting Algorithms Simple Sorting algorithms Quicksort Improving Quicksort Overview of Sorting Algorithms Given a collection of items we want to arrange them in an increasing or decreasing order. You probably have seen a number of sorting algorithms including ¾ selection sort ¾ insertion sort ¾ bubble sort ¾ quicksort ¾ tree sort using BST's In terms of efficiency: ¾ average complexity of the first three is O(n2) ¾ average complexity of quicksort and tree sort is O(n lg n) ¾ but its worst case is still O(n2) which is not acceptable In this section, we ¾ review insertion, selection and bubble sort ¾ discuss quicksort and its average/worst case analysis ¾ show how to eliminate tail recursion ¾ present another sorting algorithm called heapsort Unit 7- Sorting Algorithms 2 Selection Sort Assume that data ¾ are integers ¾ are stored in an array, from 0 to size-1 ¾ sorting is in ascending order Algorithm for i=0 to size-1 do x = location with smallest value in locations i to size-1 swap data[i] and data[x] end Complexity If array has n items, i-th step will perform n-i operations First step performs n operations second step does n-1 operations ... last step performs 1 operatio. Total cost : n + (n-1) +(n-2) + ... + 2 + 1 = n*(n+1)/2 . Algorithm is O(n2). Unit 7- Sorting Algorithms 3 Insertion Sort Algorithm for i = 0 to size-1 do temp = data[i] x = first location from 0 to i with a value greater or equal to temp shift all values from x to i-1 one location forwards data[x] = temp end Complexity Interesting operations: comparison and shift i-th step performs i comparison and shift operations Total cost : 1 + 2 + .. -

Batcher's Algorithm

18.310 lecture notes Fall 2010 Batcher’s Algorithm Prof. Michel Goemans Perhaps the most restrictive version of the sorting problem requires not only no motion of the keys beyond compare-and-switches, but also that the plan of comparison-and-switches be fixed in advance. In each of the methods mentioned so far, the comparison to be made at any time often depends upon the result of previous comparisons. For example, in HeapSort, it appears at first glance that we are making only compare-and-switches between pairs of keys, but the comparisons we perform are not fixed in advance. Indeed when fixing a headless heap, we move either to the left child or to the right child depending on which child had the largest element; this is not fixed in advance. A sorting network is a fixed collection of comparison-switches, so that all comparisons and switches are between keys at locations that have been specified from the beginning. These comparisons are not dependent on what has happened before. The corresponding sorting algorithm is said to be non-adaptive. We will describe a simple recursive non-adaptive sorting procedure, named Batcher’s Algorithm after its discoverer. It is simple and elegant but has the disadvantage that it requires on the order of n(log n)2 comparisons. which is larger by a factor of the order of log n than the theoretical lower bound for comparison sorting. For a long time (ten years is a long time in this subject!) nobody knew if one could find a sorting network better than this one. -

Hacking a Google Interview – Handout 2

Hacking a Google Interview – Handout 2 Course Description Instructors: Bill Jacobs and Curtis Fonger Time: January 12 – 15, 5:00 – 6:30 PM in 32‐124 Website: http://courses.csail.mit.edu/iap/interview Classic Question #4: Reversing the words in a string Write a function to reverse the order of words in a string in place. Answer: Reverse the string by swapping the first character with the last character, the second character with the second‐to‐last character, and so on. Then, go through the string looking for spaces, so that you find where each of the words is. Reverse each of the words you encounter by again swapping the first character with the last character, the second character with the second‐to‐last character, and so on. Sorting Often, as part of a solution to a question, you will need to sort a collection of elements. The most important thing to remember about sorting is that it takes O(n log n) time. (That is, the fastest sorting algorithm for arbitrary data takes O(n log n) time.) Merge Sort: Merge sort is a recursive way to sort an array. First, you divide the array in half and recursively sort each half of the array. Then, you combine the two halves into a sorted array. So a merge sort function would look something like this: int[] mergeSort(int[] array) { if (array.length <= 1) return array; int middle = array.length / 2; int firstHalf = mergeSort(array[0..middle - 1]); int secondHalf = mergeSort( array[middle..array.length - 1]); return merge(firstHalf, secondHalf); } The algorithm relies on the fact that one can quickly combine two sorted arrays into a single sorted array. -

Data Structures & Algorithms

DATA STRUCTURES & ALGORITHMS Tutorial 6 Questions SORTING ALGORITHMS Required Questions Question 1. Many operations can be performed faster on sorted than on unsorted data. For which of the following operations is this the case? a. checking whether one word is an anagram of another word, e.g., plum and lump b. findin the minimum value. c. computing an average of values d. finding the middle value (the median) e. finding the value that appears most frequently in the data Question 2. In which case, the following sorting algorithm is fastest/slowest and what is the complexity in that case? Explain. a. insertion sort b. selection sort c. bubble sort d. quick sort Question 3. Consider the sequence of integers S = {5, 8, 2, 4, 3, 6, 1, 7} For each of the following sorting algorithms, indicate the sequence S after executing each step of the algorithm as it sorts this sequence: a. insertion sort b. selection sort c. heap sort d. bubble sort e. merge sort Question 4. Consider the sequence of integers 1 T = {1, 9, 2, 6, 4, 8, 0, 7} Indicate the sequence T after executing each step of the Cocktail sort algorithm (see Appendix) as it sorts this sequence. Advanced Questions Question 5. A variant of the bubble sorting algorithm is the so-called odd-even transposition sort . Like bubble sort, this algorithm a total of n-1 passes through the array. Each pass consists of two phases: The first phase compares array[i] with array[i+1] and swaps them if necessary for all the odd values of of i. -

Parallel Sorting Algorithms + Topic Overview

+ Design of Parallel Algorithms Parallel Sorting Algorithms + Topic Overview n Issues in Sorting on Parallel Computers n Sorting Networks n Bubble Sort and its Variants n Quicksort n Bucket and Sample Sort n Other Sorting Algorithms + Sorting: Overview n One of the most commonly used and well-studied kernels. n Sorting can be comparison-based or noncomparison-based. n The fundamental operation of comparison-based sorting is compare-exchange. n The lower bound on any comparison-based sort of n numbers is Θ(nlog n) . n We focus here on comparison-based sorting algorithms. + Sorting: Basics What is a parallel sorted sequence? Where are the input and output lists stored? n We assume that the input and output lists are distributed. n The sorted list is partitioned with the property that each partitioned list is sorted and each element in processor Pi's list is less than that in Pj's list if i < j. + Sorting: Parallel Compare Exchange Operation A parallel compare-exchange operation. Processes Pi and Pj send their elements to each other. Process Pi keeps min{ai,aj}, and Pj keeps max{ai, aj}. + Sorting: Basics What is the parallel counterpart to a sequential comparator? n If each processor has one element, the compare exchange operation stores the smaller element at the processor with smaller id. This can be done in ts + tw time. n If we have more than one element per processor, we call this operation a compare split. Assume each of two processors have n/p elements. n After the compare-split operation, the smaller n/p elements are at processor Pi and the larger n/p elements at Pj, where i < j. -

Sorting Networks on Restricted Topologies Arxiv:1612.06473V2 [Cs

Sorting Networks On Restricted Topologies Indranil Banerjee Dana Richards Igor Shinkar [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] George Mason University George Mason University UC Berkeley October 9, 2018 Abstract The sorting number of a graph with n vertices is the minimum depth of a sorting network with n inputs and n outputs that uses only the edges of the graph to perform comparisons. Many known results on sorting networks can be stated in terms of sorting numbers of different classes of graphs. In this paper we show the following general results about the sorting number of graphs. 1. Any n-vertex graph that contains a simple path of length d has a sorting network of depth O(n log(n=d)). 2. Any n-vertex graph with maximal degree ∆ has a sorting network of depth O(∆n). We also provide several results relating the sorting number of a graph with its rout- ing number, size of its maximal matching, and other well known graph properties. Additionally, we give some new bounds on the sorting number for some typical graphs. 1 Introduction In this paper we study oblivious sorting algorithms. These are sorting algorithms whose sequence of comparisons is made in advance, before seeing the input, such that for any input of n numbers the value of the i'th output is smaller or equal to the value of the j'th arXiv:1612.06473v2 [cs.DS] 20 Jan 2017 output for all i < j. That is, for any permutation of the input out of the n! possible, the output of the algorithm must be sorted. -

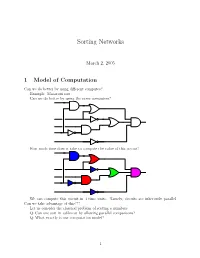

Sorting Networks

Sorting Networks March 2, 2005 1 Model of Computation Can we do better by using different computes? Example: Macaroni sort. Can we do better by using the same computers? How much time does it take to compute the value of this circuit? We can compute this circuit in 4 time units. Namely, circuits are inherently parallel. Can we take advantage of this??? Let us consider the classical problem of sorting n numbers. Q: Can one sort in sublinear by allowing parallel comparisons? Q: What exactly is our computation model? 1 1.1 Computing with a circuit We are going to design a circuit, where the inputs are the numbers, and we compare two numbers using a comparator gate: ¢¤¦© ¡ ¡ Comparator ¡£¢¥¤§¦©¨ ¡ For our drawings, we will draw such a gate as follows: ¢¡¤£¦¥¨§ © ¡£¦ So, circuits would just be horizontal lines, with vertical segments (i.e., gates) between them. A complete sorting network, looks like: The inputs come on the wires on the left, and are output on the wires on the right. The largest number is output on the bottom line. The surprising thing, is that one can generate circuits from a sorting algorithm. In fact, consider the following circuit: Q: What does this circuit does? A: This is the inner loop of insertion sort. Repeating this inner loop, we get the following sorting network: 2 Alternative way of drawing it: Q: How much time does it take for this circuit to sort the n numbers? Running time = how many time clocks we have to wait till the result stabilizes. In this case: 5 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9 In general, we get: Lemma 1.1 Insertion sort requires 2n − 1 time units to sort n numbers. -

13 Basic Sorting Algorithms

Concise Notes on Data Structures and Algorithms Basic Sorting Algorithms 13 Basic Sorting Algorithms 13.1 Introduction Sorting is one of the most fundamental and important data processing tasks. Sorting algorithm: An algorithm that rearranges records in lists so that they follow some well-defined ordering relation on values of keys in each record. An internal sorting algorithm works on lists in main memory, while an external sorting algorithm works on lists stored in files. Some sorting algorithms work much better as internal sorts than external sorts, but some work well in both contexts. A sorting algorithm is stable if it preserves the original order of records with equal keys. Many sorting algorithms have been invented; in this chapter we will consider the simplest sorting algorithms. In our discussion in this chapter, all measures of input size are the length of the sorted lists (arrays in the sample code), and the basic operation counted is comparison of list elements (also called keys). 13.2 Bubble Sort One of the oldest sorting algorithms is bubble sort. The idea behind it is to make repeated passes through the list from beginning to end, comparing adjacent elements and swapping any that are out of order. After the first pass, the largest element will have been moved to the end of the list; after the second pass, the second largest will have been moved to the penultimate position; and so forth. The idea is that large values “bubble up” to the top of the list on each pass. A Ruby implementation of bubble sort appears in Figure 1. -

Title the Complexity of Topological Sorting Algorithms Author(S)

Title The Complexity of Topological Sorting Algorithms Author(s) Shoudai, Takayoshi Citation 数理解析研究所講究録 (1989), 695: 169-177 Issue Date 1989-06 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/101392 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 数理解析研究所講究録 第 695 巻 1989 年 169-177 169 Topological Sorting の NLOG 完全性について -The Complexity of Topological Sorting Algorithms- 正代 隆義 Takayoshi Shoudai Department of Mathematics, Kyushu University We consider the following problem: Given a directed acyclic graph $G$ and vertices $s$ and $t$ , is $s$ ordered before $t$ in the topological order generated by a given topological sorting algorithm? For known algorithms, we show that these problems are log-space complete for NLOG. It also contains the lexicographically first topological sorting problem. The algorithms use the result that NLOG is closed under conplementation. 1. Introduction The topological sorting problem is, given a directed acyclic graph $G=(V, E)$ , to find a total ordering of its vertices such that if $(v, w)$ is an edge then $v$ is ordered before $w$ . It has important applications for analyzing programs and arranging the words in the glossary [6]. Moreover, it is used in designing many efficient sequential algorithms, for example, the maximum flow problem [11]. Some techniques for computing topological orders have been developed. The algorithm by Knuth [6] that computes the lexicographically first topological order runs in time $O(|E|)$ . Tarjan [11] also devised an $O(|E|)$ time algorithm by employ- ing the depth-first search method. Dekel, Nassimi and Sahni [4] showed a parallel algorithm using the parallel matrix multiplication technique. Ruzzo also devised a simple $NL^{*}$ -algorithm as is stated in [3]. -

Foundations of Differentially Oblivious Algorithms

Foundations of Differentially Oblivious Algorithms T-H. Hubert Chan Kai-Min Chung Bruce Maggs Elaine Shi August 5, 2020 Abstract It is well-known that a program's memory access pattern can leak information about its input. To thwart such leakage, most existing works adopt the technique of oblivious RAM (ORAM) simulation. Such an obliviousness notion has stimulated much debate. Although ORAM techniques have significantly improved over the past few years, the concrete overheads are arguably still undesirable for real-world systems | part of this overhead is in fact inherent due to a well-known logarithmic ORAM lower bound by Goldreich and Ostrovsky. To make matters worse, when the program's runtime or output length depend on secret inputs, it may be necessary to perform worst-case padding to achieve full obliviousness and thus incur possibly super-linear overheads. Inspired by the elegant notion of differential privacy, we initiate the study of a new notion of access pattern privacy, which we call \(, δ)-differential obliviousness". We separate the notion of (, δ)-differential obliviousness from classical obliviousness by considering several fundamental algorithmic abstractions including sorting small-length keys, merging two sorted lists, and range query data structures (akin to binary search trees). We show that by adopting differential obliv- iousness with reasonable choices of and δ, not only can one circumvent several impossibilities pertaining to full obliviousness, one can also, in several cases, obtain meaningful privacy with little overhead relative to the non-private baselines (i.e., having privacy \almost for free"). On the other hand, we show that for very demanding choices of and δ, the same lower bounds for oblivious algorithms would be preserved for (, δ)-differential obliviousness. -

Selected Sorting Algorithms

Selected Sorting Algorithms CS 165: Project in Algorithms and Data Structures Michael T. Goodrich Some slides are from J. Miller, CSE 373, U. Washington Why Sorting? • Practical application – People by last name – Countries by population – Search engine results by relevance • Fundamental to other algorithms • Different algorithms have different asymptotic and constant-factor trade-offs – No single ‘best’ sort for all scenarios – Knowing one way to sort just isn’t enough • Many to approaches to sorting which can be used for other problems 2 Problem statement There are n comparable elements in an array and we want to rearrange them to be in increasing order Pre: – An array A of data records – A value in each data record – A comparison function • <, =, >, compareTo Post: – For each distinct position i and j of A, if i < j then A[i] ≤ A[j] – A has all the same data it started with 3 Insertion sort • insertion sort: orders a list of values by repetitively inserting a particular value into a sorted subset of the list • more specifically: – consider the first item to be a sorted sublist of length 1 – insert the second item into the sorted sublist, shifting the first item if needed – insert the third item into the sorted sublist, shifting the other items as needed – repeat until all values have been inserted into their proper positions 4 Insertion sort • Simple sorting algorithm. – n-1 passes over the array – At the end of pass i, the elements that occupied A[0]…A[i] originally are still in those spots and in sorted order. -

Visualizing Sorting Algorithms Brian Faria Rhode Island College, [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2017 Visualizing Sorting Algorithms Brian Faria Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Education Commons, Mathematics Commons, and the Other Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Faria, Brian, "Visualizing Sorting Algorithms" (2017). Honors Projects Overview. 127. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/127 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VISUALIZING SORTING ALGORITHMS By Brian J. Faria An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Faculty of Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2017 Abstract This paper discusses a study performed on animating sorting al- gorithms as a learning aid for classroom instruction. A web-based animation tool was created to visualize four common sorting algo- rithms: Selection Sort, Bubble Sort, Insertion Sort, and Merge Sort. The animation tool would represent data as a bar-graph and after se- lecting a data-ordering and algorithm, the user can run an automated animation or step through it at their own pace. Afterwards, a study was conducted with a voluntary student population at Rhode Island College who were in the process of learning algorithms in their Com- puter Science curriculum. The study consisted of a demonstration and survey that asked the students questions that may show improve- ment when understanding algorithms.