Workingpaper Workingpaper # 96 •Julio 2008 and Dynamicallyinterrelated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relações Internacionais, Política Externa E Diplomacia Brasileira Pensamento E Ação

coleção Internacionais Relações Relações coleção coleção Internacionais “É com satisfação que a Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão publica Relações 830 Um dos mais importantes intelectuais brasi- Internacionais, política externa e diplomacia brasileira: pensamento e ação, do leiros, Celso Lafer foi por duas vezes ministro professor Celso Lafer, embaixador e ex-ministro das Relações Exteriores. O das Relações Exteriores (1992 e 2001-2002), livro reúne coletânea de textos ligados ao direito, às relações internacionais e à Celso Lafer ao lado de outros relevantes cargos exercidos política externa brasileira, criteriosamente selecionados pelo autor e extraídos tanto na academia – em especial como Celso Lafer (São Paulo, 1941) foi até a sua de sua vasta produção literária e cientí ca. [...] A experiência como diplomata Celso Lafer professor na Faculdade de Direito do Largo aposentadoria em 2011 professor-titular do e chanceler colocou o extraordinário preparo acadêmico a serviço da arte da de S. Francisco –, quanto no setor público, Departamento de Filoso a e Teoria Geral do diplomacia e aos desa os de quem por ofício, em dois governos distintos, ajudou no Brasil e no exterior – embaixador do Direito da Faculdade de Direito da USP, da qual na formulação e respondeu pela condução da política externa brasileira. Seu papel Brasil em Genebra (1995-98), ministro do é professor emérito, tendo exercido por duas e sua in uência na sociedade transcendem essa experiência circunstancial. Seus Desenvolvimento e da Indústria e Comércio vezes (1992 e 2001-2002) o cargo de ministro livros, ensaios, artigos, entrevistas e comentários na mídia nas últimas décadas (1999) –, bem como no setor privado, ademais de Estado das Relações Exteriores; é PhD em dão a medida de sua importância como formador de opinião. -

ANNEX II Background Information on the WTO

ANNEX II Background Information on the WTO Doha Development Agenda 1. Doha Ministerial Declaration 2. Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health 3. Doha Declaration on Implementation-Related Issues and Concerns 4. Doha Work Programme 5. Amendment of the TRIPS Agreement 6. Hong Kong Ministerial Declaration 7. U.S. Submissions to the WTO in Support of the Doha Development Agenda 8. WTO Affinity Groups in the DDA Institutional Issues 2. Membership of the WTO 3. 2007 WTO Budget Contributions 4. 2007-8 Budget for the WTO Secretariat 5. Waivers Currently in Force 6. WTO Secretariat Personnel Statistics 7. WTO Accession Application and Status 8. Indicative List of Governmental and Non-Governmental Panellists 9. Appellate Body Membership 10. Where to Find More Information on the WTO WORLD TRADE WT/MIN(01)/DEC/1 20 November 2001 ORGANIZATION (01-5859) MINISTERIAL CONFERENCE Fourth Session Doha, 9 - 14 November 2001 MINISTERIAL DECLARATION Adopted on 14 November 2001 1. The multilateral trading system embodied in the World Trade Organization has contributed significantly to economic growth, development and employment throughout the past fifty years. We are determined, particularly in the light of the global economic slowdown, to maintain the process of reform and liberalization of trade policies, thus ensuring that the system plays its full part in promoting recovery, growth and development. We therefore strongly reaffirm the principles and objectives set out in the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, and pledge to reject the use of protectionism. 2. International trade can play a major role in the promotion of economic development and the alleviation of poverty. -

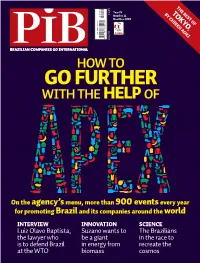

Go Further with the Help Of

THE BEST OF 5,00 Year IV ¤ BY CHIEKOTOKYO AOKI Number 11 Nov/Dez 2010 , totum R$ 12,00 HOW TO GO FURTHER WITH THE HELP OF On the agency’s menu, more than 900 events every year for promoting Brazil and its companies around the world INTERVIEW INNOVATION SCIENCE Luiz Olavo Baptista, Suzano wants to The Brazilians the lawyer who be a giant in the race to is to defend Brazil in energy from recreate the at the WTO biomass cosmos Contents 66 RICARDO TELLES 40COVER How ApexBrasil works to convince the world of the quality of the products made in Brazil Nely Caixeta HANDOUT CERN 24 30 HANDOUT 80 10 76 HANDOUT HANDOUT THE YEATMAN JNTO BEACON GLOBE-TROTTER 30 The Peruvian fi rst lady, Pilar Nores de García INTERNATIONALIZATION 76 EXECUTIVE TRAVEL ANTENNA has begun to export initiatives for combating 58 São Paulo works to integrate the Latin New York at the price of a banana, an island of 10 Hand-made toys for the children now win over the poverty American capital markets into the happiness in Abu Dhabi and new European market Nely Caixeta BMF&Bovespa airline routes to Brazil. Andressa Rovani Eliane Simonetti Marco Rezende TECHNOLOGY A VIEW FROM CAPITOL HILL 32 Suzano wants to reach its 100th BUSINESS EXPRESS TOURISM 22 What Brazil gains or loses from the new anniversary as a world biotechnology 64 Decades after the arrival of the Brazilian Corporate leader Chieko Aoki combines the traditional complexion of the United States Congress giant by investing in innovation multinationals in Africa, now the banks are and the modern tracking the route from -

Related Document

WORLD TRADE WT/AB/9 30 January 2008 ORGANIZATION (08-0422) APPELLATE BODY ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2007 JANUARY 2008 The Appellate Body welcomes comments and inquiries regarding this report at the following address: Appellate Body Secretariat World Trade Organization rue de Lausanne 154 1211 Geneva, Switzerland email: [email protected] <www.wto.org/appellatebody> WT/AB/9 Page i CONTENTS I. Introduction.................................................................................................................................1 II. Composition of the Appellate Body............................................................................................3 III. Appeals........................................................................................................................................6 IV. Appellate Body Reports ..............................................................................................................8 A. Agreements Covered ......................................................................................................8 B. Findings and Conclusions .............................................................................................9 V. Participants and Third Participants ...........................................................................................15 VI. Working Procedures for Appellate Review ..............................................................................18 VII. Arbitrations under Article 21.3(c) of the DSU..........................................................................19 -

Printed by the WTO Secretariat a PPELLATE BODY ANNUAL REPORT for 2003

Printed by the WTO Secretariat A PPELLATE BODY ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. COMPOSITION OF THE APPELLATE BODY....................................................................... 1 II. APPEALS FILED................................................................................................................................ 3 III. APPELLATE BODY REPORTS..................................................................................................... 5 IV. SUBJECT MATTER OF APPEALS................................................................................................ 7 V. PARTICIPANTS AND THIRD PARTICIPANTS...................................................................... 9 VI. WORKING PROCEDURES FOR APPELLATE REVIEW .................................................. 12 VII. ARBITRATIONS UNDER ARTICLE 21.3(c) OF THE DSU................................................ 13 VIII. TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE.......................................................................................................... 14 IX. OTHER DEVELOPMENTS.......................................................................................................... 15 ANNEX 1 BIOGRAPHIES OF APPELLATE BODY MEMBERS .......................................................... 16 ANNEX 2 APPEALS FILED BETWEEN 1996 AND 2003 ....................................................................... 21 ANNEX 3 SUMMARIES OF APPELLATE BODY REPORTS CIRCULATED IN 2003 ................. 22 ANNEX 4 WTO AGREEMENTS COVERED IN APPELLATE BODY REPORTS CIRCULATED -

Annual Report 2009 APPELL a TE BOD Y

Annual Report 2009 APPELLATE BODY The Appellate Body welcomes comments and inquiries regarding this report at the following address: Appellate Body Secretariat World Trade Organization rue de Lausanne 154 1211 Geneva, Switzerland email: [email protected] <www.wto.org/appellatebody> APPELLATE BODY MEMBERS: AS AT 1 JANUARY 2009 From left to right: Mr. Giorgio Sacerdoti; Ms. Jennifer Hillman; Mr. Shotaro Oshima; Ms. Yuejiao Zhang; Mr. Luiz Olavo Baptista; Ms. Lilia R. Bautista; Mr. David Unterhalter. APPELLATE BODY MEMBERS: AS AT 31 DECEMBER 2009 From left to right: Mr. Ricardo Ramírez-Hernandez; Ms. Yuejiao Zhang; Mr. Peter Van den Bossche; Ms. Jennifer Hillman; Mr. David Unterhalter; Ms. Lilia R. Bautista; Mr. Shotaro Oshima. ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2009 APPELLATE BODY i TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS ANNUAL REPORT ..............................................................................................................ii FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................................................................iii I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. COMPOSITION OF THE APPELLATE BODY ............................................................................................................. 4 III. APPEALS .................................................................................................................................................................................