ISEAS Working Paper 2014 #4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Politics in Malaysia I

Reproduced from Personalized Politics: The Malaysian State under Mahathir, by In-Won Hwang (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2003). This version was obtained electronically direct from the publisher on condition that copyright is not infringed. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior permission of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Individual articles are available at < http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg > New Politics in Malaysia i © 2003 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio- political, security and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is governed by a twenty-two-member Board of Trustees comprising nominees from the Singapore Government, the National University of Singapore, the various Chambers of Commerce, and professional and civic organizations. An Executive Committee oversees day-to-day operations; it is chaired by the Director, the Institute’s chief academic and administrative officer. © 2003 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore SILKWORM BOOKS, Thailand INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES, Singapore © 2003 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore First published in Singapore in 2003 by Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 E-mail: [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg First published in Thailand in 2003 by Silkworm Books 104/5 Chiang Mai-Hot Road, Suthep, Chiang Mai 50200 Ph. -

Trends in Southeast Asia

ISSN 0219-3213 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN TRS9/17s ISBN 978-981-4786-44-7 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 786447 Trends in Southeast Asia 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 1 15/8/17 8:38 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and the Singapore APEC Study Centre. ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 2 15/8/17 8:38 AM 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 3 15/8/17 8:38 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2017 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Monthly News Scan

MONTHLY NEWS SCAN Tinjauan Berita Bulanan Compiled by IDS Vol. 25 Issue 1 IDS Online http://www.ids.org.my 1 – 31 January 2020 HIGHLIGHTS National Statistics. Growth was push by President Moon Jae-in's FOCUS slightly stronger in September and government and a jump in factory October than previously thought, but investment that included spending on fell 0.3% in November, dragging equipment for making •Global economy snapback to prove down the three-month figure. The semiconductors. (23 January, The elusive despite market joy: ONS said growth in the economy Straits Times) Reuters polls year-on-year was at its lowest since •OPEC aims to extend oil output the spring of 2012. Growth in French economy shrinks in fourth cuts through June, alarmed by construction was offset by a quarter as strikes bite: The French China virus weakening service sector, while economy unexpectedly shrank in the •Boost to Malaysia’s GDP •MITI welcomes US-China phase manufacturing was “lacklustre”. (13 final quarter of 2019 as manufacturing one trade deal, positive for open January, BBC News) output slumped in the face of strikes economies over an unpopular pension reform, •Sabah-S’wak link road Japan warns about risks to putting more pressure on President construction to start June economy from China virus Emmanuel Macron. Macron has so far •RM3 mln to upgrade basic outbreak: Japanese Economy been able to point to resilient growth facilities in 10 villages Minister Yasutoshi Nishimura warned and job creation to justify his pro- recently that corporate profits and business reforms. But he faced a wave INTERNATIONAL factory production might take a hit of protests over the last year, first from from the coronavirus outbreak in the “yellow vests” movement and now ANTARABANGSA China that has rattled global markets from those opposed to his plans to and chilled confidence. -

Isu Pesawah Miskin Jadi Perhatian Utama Kerajaan

Headline Isu pesawah miskin jadi perhatian utama kerajaan: PM MediaTitle Harian Ekspres (KK) Date 12 Jun 2019 Color Full Color Section Tempatan Circulation 25,055 Page No 1 Readership 75,165 Language Malay ArticleSize 342 cm² Journalist N/A AdValue RM 1,817 Frequency Daily (EM) PR Value RM 5,451 dari China Utara > 2 disimbah cat merah! > 3 Samarinda > 5 anak >6 Isu pesawah miskin jadi perhatian utama kerajaan: PM PUTRAJAYA: Isu "Kita dah ada terima beberapa Akhtar Aziz. sama negara juga perlu memastikan buah-buahan seperti Harumanis kemiskinan dalam perkara yang menyebabkan mereka Dr Mahathir berkata kaedah jaminan makanan. (mangga), nanas dan semua itu boleh kalangan pesawah menjadi miskin. Yang pertama ialah penanaman padi perlu clipert- "Kita perlu mengenal pasti bidang memberi pulangan yang lebih baik. dan jaminan mereka mempunyai pemegangan yang ingkatkan selain cara pesawah meng- yang boleh dilakukan untuk sekurang- "Mungkin mereka (penanam padi) makanan menjadi terlalu kecil untuk memberi perolehan gunakan baja bagi meningkatkan hasil kurangnya membantu petani perlu memperuntukkan sebahagian perhatian utama ker- pulangan yang baik. tanaman serta tidak memaksa mereka meningkatkan pendapatan dan pada tanah mereka untuk menanam tana- ajaan. "Yang keduanya mereka tidak menanam padi sahaja. masa yang sama tidak membebankan man lain," kata beliau. Perdana Menteri efisien. Di atas tanah yang satu ekar "Mereka boleh ada tanaman gantian kos kepada pengguna. Harga peng- Perdana menteri berkata kerajaan Dr Mahathir Mo- boleh keluar lapan tan, mereka keluar yang boleh beri pulangan yang lebih guna tidak boleh naik untuk menam- juga merancang untuk mengurangkan hamad (gambar) berkata antara faktor cuma empat tan," kata perdana menteri baik umpamanya tanaman kontan bah pendapatan petani," kata Dr import makanan kepada US$30 bilion, yang menyumbang kepada kemiskinan pada sidang akhbar selepas mem- yang mana boleh dituai tiga kali, empat Mahathir. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

ANFREL E-BULLETIN ANFREL E-Bulletin Is ANFREL’S Quarterly Publication Issued As Part of the Asian Republic of Electoral Resource Center (AERC) Program

Volume 2 No.1 January – March 2015 E-BULLETIN The Dili Indicators are a practical distilla- voting related information to enable better 2015 Asian Electoral tion of the Bangkok Declaration for Free informed choices by voters. Stakeholder Forum and Fair Elections, the set of principles endorsed at the 2012 meeting of the Participants were also honored to hear Draws Much Needed AES Forum. The Indicators provide a from some of the most distinguished practical starting point to assess the and influential leaders of Timor-Leste’s Attention to Electoral quality and integrity of elections across young democracy. The President of the region. Timor-Leste, José Maria Vasconcelos Challenges in Asia A.K.A “Taur Matan Ruak”, opened the More than 120 representatives from twen- Forum, while Nobel Laureate Dr. Jose The 2nd Asian Electoral Stakeholder ty-seven countries came together to share Ramos-Jorta, Founder of the State Dr. ANFREL ACTIVITIES ANFREL Forum came to a successful close on their expertise and focus attention on the Marí Bim Hamude Alkatiri, and the coun- March 19 after two days of substantive most persistent challenges to elections in try’s 1st president after independence discussions and information sharing the region. Participants were primarily and Founder of the State Kay Rala 1 among representatives of Election from Asia, but there were also participants Xanana Gusmão also addressed the Management Bodies and Civil Society from many of the countries of the Commu- attendees. Each shared the wisdom Organizations (CSOs). nity of Portuguese Speaking Countries gained from their years of trying to (CPLP). The AES Forum offered represen- consolidate Timorese electoral democ- Coming two years after the inaugural tatives from Electoral Management Bodies racy. -

Guan Eng Can't Tell Right from Wrong Malaysiakini.Com Feb 5, 2014

Wanita MCA: Guan Eng can't tell right from wrong MalaysiaKini.com Feb 5, 2014 Wanita MCA chair Heng Seai Kie has taken DAP secretary-general Lim Guan Eng to task for "defending the indefensible" as the war of words escalates over Seputeh MP Teresa Kok's stirring video work. Heng said Lim was "incapable of differentiating right and wrong" as he could not see the havoc wreaked by Kok's Chinese New Year 11-minute clip, which satires the political situation in the country. Amidst uproar by a few Umno cabinet ministers and police investigations, Lim - who is also Penang chief minister - had said yesterday that he saw "nothing amiss" with the video and considered BN's exaggerated outrage a mere political ploy. But Heng (right) begged to differ, saying that the video published on the Internet on Jan 27 "will not only destroy the country's image, but also affect foreign investment and tourism which will impact the national economy, victimise the rakyat and the nation". "If Lim can spend some time and watch the video and also read the feedback from netizens, he will understand how Kok's video has created controversies and differences among the people, especially between the Malays and Chinese. "Thanks to the video, Kok cannot run away from contributing to the polarisation of the people and jeopardising national unity," Heng stressed in a statement. She damned the video, which features Kok as a talk-show host interviewing a "panel of experts" on what to expect in the Chinese Lunar Year of the Horse. -

Malaysian Prime Minister Hosted by HSBC at Second Belt and Road Forum

News Release 30 April 2019 Malaysian Prime Minister hosted by HSBC at second Belt and Road Forum Peter Wong, Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, together with Stuart Milne, Chief Executive Officer, HSBC Malaysia, hosted a meeting for a Malaysian government delegation led by Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Prime Minister of Malaysia, with HSBC’s Chinese corporate clients. The meeting took place in Beijing on the sidelines of the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, in which Mr. Wong represented HSBC. Dr. Mahathir together with the Malaysian Ministers met with Mr. Wong and executives from approximately 20 Chinese companies to discuss opportunities in Malaysia in relation to the Belt and Road Initiative. Also present at the meeting were Saifuddin Abdullah, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Mohamed Azmin Ali, Minister of Economic Affairs; Darell Leiking, Minister of International Trade and Industry; Anthony Loke, Minister of Transport; Zuraida Kamaruddin, Minister of Housing and Local Government; Salahuddin Ayub, Minister of Agriculture and Agro- Based Industry; and Mukhriz Mahathir, Chief Minister of Kedah. Ends/more Media enquiries to: Marlene Kaur +603 2075 3351 [email protected] Joanne Wong +603 2075 6169 [email protected] About HSBC Malaysia HSBC's presence in Malaysia dates back to 1884 when the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited (a company under the HSBC Group) established its first office in the country, on the island of Penang, with permission to issue currency notes. HSBC Bank Malaysia Berhad was locally incorporated in 1984 and is a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited. -

Anwar Ibrahim

- 8 - CL/198/12(b)-R.1 Lusaka, 23 March 2016 Malaysia MAL/15 - Anwar Ibrahim Decision adopted by consensus by the IPU Governing Council at its 198 th session (Lusaka, 23 March 2016) 2 The Governing Council of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, Referring to the case of Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim, a member of the Parliament of Malaysia, and to the decision adopted by the Governing Council at its 197 th session (October 2015), Taking into account the information provided by the leader of the Malaysian delegation to the 134 th IPU Assembly (March 2016) and the information regularly provided by the complainants, Recalling the following information on file: - Mr. Anwar Ibrahim, Finance Minister from 1991 to 1998 and Deputy Prime Minister from December 1993 to September 1998, was dismissed from both posts in September 1998 and arrested on charges of abuse of power and sodomy. He was found guilty on both counts and sentenced, in 1999 and 2000 respectively, to a total of 15 years in prison. On 2 September 2004, the Federal Court quashed the conviction in the sodomy case and ordered Mr. Anwar Ibrahim’s release, as he had already served his sentence in the abuse of power case. The IPU had arrived at the conclusion that the motives for Mr. Anwar Ibrahim’s prosecution were not legal in nature and that the case had been built on a presumption of guilt; - Mr. Anwar Ibrahim was re-elected in August 2008 and May 2013 and became the de facto leader of the opposition Pakatan Rakyat (The People’s Alliance); - On 28 June 2008, Mohammed Saiful Bukhari Azlan, a former male aide in Mr. -

Anti- Corruption Toolkit for Civic Activists

ANTI- CORRUPTION TOOLKIT FOR CIVIC ACTIVISTS Leveraging research, advocacy and the media to push for effective reform Anti-Corruption Toolkit for Civic Activists Lead Authors: Angel Sharma, Milica Djuric, Anna Downs and Abigail Bellows Contributing Writers: Prakhar Sharma, Dina Sadek, Elizabeth Donkervoort and Eguiar Lizundia Copyright © 2020 International Republican Institute. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the International Republican Institute. Requests for permission should include the following information: • The title of the document for which permission to copy material is desired. • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, e-mail address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: Attn: Department of External Affairs International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] This publication was made possible through the support provided by the National Endowment for Democracy. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Module 1: Research Methods and Security 2 Information and Evidence Gathering 4 Open Source 4 Government-Maintained Records 5 Interviews -

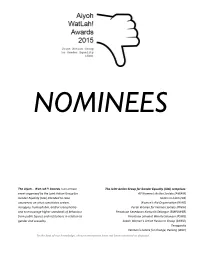

The Joint Action Group for Gender Equality

NOMINEES The Aiyoh... Wat Lah?! Awards is an annual The Joint Action Group for Gender Equality (JAG) comprises: event organised by the Joint Action Group for All Women's Action Society (AWAM) Gender Equality (JAG) intended to raise Sisters in Islam (SIS) awareness on what constitutes sexism, Women's Aid Organisation (WAO) misogyny, homophobia, and/or transphobia Perak Women for Women Society (PWW) and to encourage higher standards of behaviour Persatuan Kesedaran Komuniti Selangor (EMPOWER) from public figures and institutions in relation to Persatuan Sahabat Wanita Selangor (PSWS) gender and sexuality. Sabah Women’s Action Resource Group (SAWO) Tenaganita Women’s Centre for Change, Penang (WCC) To the best of our knowledge, these nominations have not been retracted or disputed. CATEGORY: FOOT IN MOUTH Nominee Background and basis for nomination 1 “Most Malays are sensitive Deputy Home Minister Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar is alleged to have made this to [the rape of] teenage statement in response to the release of a report that statutory rape figures are girls…Non-Malays are higher in the Malay community than amongst non-Malays. probably less sensitive towards this.” It is insulting to suggest that statutory rape is a racial issue. The Deputy Home Minister later claimed that the statement was taken out of context, but there is 18 March no context in which it is appropriate to allow the issue of ethnicity to subjugate the very universal problem of child rape. It is also an issue that someone of this high standing in Parliament is seemingly attempting to sweep this beneath the carpet, instead of treating it as an issue that needs serious attention. -

Malaysia Politics

March 10, 2020 Malaysia Politics PN Coalition Government Cabinet unveiled Analysts PM Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin unveiled his Cabinet with no DPM post and replaced by Senior Ministers, and appointed a banker as Finance Minister. Suhaimi Ilias UMNO and PAS Presidents are not in the lineup. Cabinet formation (603) 2297 8682 reduces implementation risk to stimulus package. Immediate challenges [email protected] are navigating politics and managing economy amid risk of a no Dr Zamros Dzulkafli confidence motion at Parliament sitting on 18 May-23 June 2020 and (603) 2082 6818 economic downsides as crude oil price slump adds to the COVID-19 [email protected] outbreak. Ramesh Lankanathan No DPM but Senior Ministers instead; larger Cabinet (603) 2297 8685 reflecting coalition makeup; and a banker as [email protected] Finance Minister William Poh Chee Keong Against the long-standing tradition, there is no Deputy PM post in this (603) 2297 8683 Cabinet. The Constitution also makes no provision on DPM appointment. [email protected] ECONOMICS Instead, Senior Minister status are assigned to the Cabinet posts in charge of 1) International Trade & Industry, 2) Defence, 3) Works, and 4) Education portfolios. These Senior Minister posts are distributed between what we see as key representations in the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition i.e. former PKR Deputy President turned independent Datuk Seri Azmin Ali (International Trade & Industry), UMNO Vice President Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob (Defence), Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS) Chief Whip Datuk Seri Fadillah Yusof (Works) and PM’s party Parti Pribumi Malaysia Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) Supreme Council member Dr Mohd Radzi Md Jidin (Education).