How Japanese Industry Is Rebuilding the Rust Belt By: Kenney, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

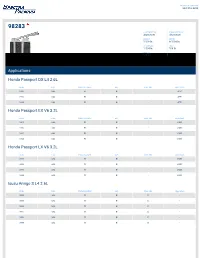

Applications Honda Passport DX L4 2.6L Honda Passport EX V6 3.2L

TECHNICAL SUPPORT 888-910-8888 98283 CORE MATERIAL TANK MATERIAL Aluminum Aluminum HEIGHT WIDTH 5-3/8 In. 6-1/16 In. THICKNESS INLET 1-1/4 In. 5/8 In. OUTLET 5/8 In. Applications Honda Passport DX L4 2.6L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1996 GAS FI N - 4ZE1 1995 GAS FI N - 4ZE1 1994 GAS FI N - 4ZE1 Honda Passport EX V6 3.2L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1997 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1996 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1995 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1994 GAS FI N - 6VD1 Honda Passport LX V6 3.2L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1997 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1996 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1995 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1994 GAS FI N - 6VD1 Isuzu Amigo S L4 2.6L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1994 GAS FI N E - 1993 GAS FI N E - 1992 GAS FI N E - 1991 GAS FI N E - 1990 GAS FI N E - 1989 GAS FI N E - Isuzu Amigo S L4 2.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1993 GAS CARB N L - 1992 GAS CARB N L - 1991 GAS CARB N L - 1990 GAS CARB N L - 1989 GAS CARB N L - Isuzu Amigo XS L4 2.6L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1994 GAS FI N E - 1993 GAS FI N E - 1992 GAS FI N E - 1991 GAS FI N E - 1990 GAS FI N E - 1989 GAS FI N E - Isuzu Amigo XS L4 2.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. -

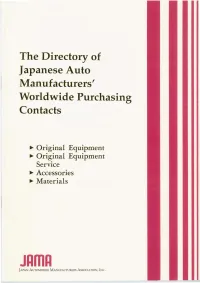

Contacts in Japan Contacts in Asia

TheDirectoryof JapaneseAuto Manufacturers′ WbrldwidePurchaslng ● Contacts ● トOriginalEqulpment ● トOriginalEqulpment Service トAccessories トMaterials +RmR JA払NAuTOMOBILEMANUFACTURERSAssocIATION′INC. DAIHATSU CONTACTS IN JAPAN CONTACTS IN ASIA OE, Service, Accessories and Material OE Parts for Asian Plants: P.T. Astra Daihatsu Motor Daihatsu Motor Co., Ltd. JL. Gaya Motor 3/5, Sunter II, Jakarta 14350, urchasing Div. PO Box 1166 Jakarta 14011, Indonesia 1-1, Daihatsu-cho, Ikeda-shi, Phone: 62-21-651-0300 Osaka, 563-0044 Japan Fax: 62-21-651-0834 Phone: 072-754-3331 Fax: 072-751-7666 Perodua Manufacturing Sdn. Bhd. Lot 1896, Sungai Choh, Mukim Serendah, Locked Bag No.226, 48009 Rawang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Phone: 60-3-6092-8888 Fax: 60-3-6090-2167 1 HINO CONTACTS IN JAPAN CONTACTS IN ASIA OE, Service, Aceessories and Materials OE, Service Parts and Accessories Hino Motors, Ltd. For Indonesia Plant: Purchasing Planning Div. P.T. Hino Motors Manufacturing Indonesia 1-1, Hinodai 3-chome, Hino-shi, Kawasan Industri Kota Bukit Indah Blok D1 No.1 Tokyo 191-8660 Japan Purwakarta 41181, Phone: 042-586-5474/5481 Jawa Barat, Indonesia Fax: 042-586-5477 Phone: 0264-351-911 Fax: 0264-351-755 CONTACTS IN NORTH AMERICA For Malaysia Plant: Hino Motors (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd. OE, Service Parts and Accessories Lot P.T. 24, Jalan 223, For America Plant: Section 51A 46100, Petaling Jaya, Hino Motors Manufacturing U.S.A., Inc. Selangor, Malaysia 290 S. Milliken Avenue Phone: 03-757-3517 Ontario, California 91761 Fax: 03-757-2235 Phone: 909-974-4850 Fax: 909-937-3480 For Thailand Plant: Hino Motors Manufacturing (Thailand)Ltd. -

Suzuki Announces FY2019 Vehicle Recycling Results in Japan

22 June 2020 Suzuki Announces FY2019 Vehicle Recycling Results in Japan Suzuki Motor Corporation has today announced the results of vehicle recycling for FY2019 (April 2019 to March 2020) in Japan, based on the Japan Automobile Recycling Law*1. In line with the legal mandate, Suzuki is responsible for promoting appropriate treatment and recycling of automobile shredder residue (ASR), airbags, and fluorocarbons through recycling fee deposited from customers. Recycling of these materials are appropriately, smoothly, and efficiently conducted by consigning the treatment to Japan Auto Recycling Partnership as for airbags and fluorocarbons, and to Automobile Shredder Residue Recycling Promotion Team*2 as for ASR. The total cost of recycling these materials was 3,640 million yen. Recycling fees and income generated from the vehicle-recycling fund totalled 4,150 million yen, contributing to a net surplus of 510 million yen. For the promotion of vehicle recycling, Suzuki contributed a total of 370 million yen from the above net surplus, to the Japan Foundation for Advanced Auto Recycling, and 20 million yen for the advanced recycling business of the Company. For the mid-and long-term, Suzuki continues to make effort in stabilising the total recycling costs. Moreover, besides the recycling costs, the Company bears 120 million yen as management-related cost of Japan Automobile Recycling Promotion Center and recycling-related cost of ASR. The results of collection and recycling of the materials are as follows. 1. ASR - 60,388.3 tons of ASR were collected from 450,662 units of end-of-life vehicles - Recycling rate was 96.7%, exceeding the legal target rate of 70% set in FY2015 since FY2008 2. -

Defendants and Auto Parts List

Defendants and Parts List PARTS DEFENDANTS 1. Wire Harness American Furukawa, Inc. Asti Corporation Chiyoda Manufacturing Corporation Chiyoda USA Corporation Denso Corporation Denso International America Inc. Fujikura America, Inc. Fujikura Automotive America, LLC Fujikura Ltd. Furukawa Electric Co., Ltd. G.S. Electech, Inc. G.S. Wiring Systems Inc. G.S.W. Manufacturing Inc. K&S Wiring Systems, Inc. Kyungshin-Lear Sales And Engineering LLC Lear Corp. Leoni Wiring Systems, Inc. Leonische Holding, Inc. Mitsubishi Electric Automotive America, Inc. Mitsubishi Electric Corporation Mitsubishi Electric Us Holdings, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd. Sumitomo Electric Wintec America, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Wiring Systems, Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems (U.S.A.) Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems, Ltd. S-Y Systems Technologies Europe GmbH Tokai Rika Co., Ltd. Tram, Inc. D/B/A Tokai Rika U.S.A. Inc. Yazaki Corp. Yazaki North America Inc. 2. Instrument Panel Clusters Continental Automotive Electronics LLC Continental Automotive Korea Ltd. Continental Automotive Systems, Inc. Denso Corp. Denso International America, Inc. New Sabina Industries, Inc. Nippon Seiki Co., Ltd. Ns International, Ltd. Yazaki Corporation Yazaki North America, Inc. Defendants and Parts List 3. Fuel Senders Denso Corporation Denso International America, Inc. Yazaki Corporation Yazaki North America, Inc. 4. Heater Control Panels Alps Automotive Inc. Alps Electric (North America), Inc. Alps Electric Co., Ltd Denso Corporation Denso International America, Inc. K&S Wiring Systems, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd. Sumitomo Electric Wintec America, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Wiring Systems, Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems (U.S.A.) Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems, Ltd. Tokai Rika Co., Ltd. Tram, Inc. 5. Bearings Ab SKF JTEKT Corporation Koyo Corporation Of U.S.A. -

Honda Cr-V Honda Element Honda Odyssey Honda Pilot

55336 ACURA CL SERIES HONDA CR-V ACURA INTEGRA HONDA ELEMENT ACURA MDX HONDA ODYSSEY ACURA RL SERIES HONDA PILOT ACURA TL SERIES HONDA PRELUDE HONDA ACCORD ISUZU OASIS 12/04/1213 A. Locate the vehicles taillight wiring harness behind the rear bumper. The harness will have connectors similar to those on the T-connector harness and can be found in the following positions: Passenger Cars: 1. Open the trunk and remove the plastic screw that secures the trunk liner on the passengers side of the trunk. Peel back the trunk liner to expose the vehicles harness. 1996-1999 Isuzu Oasis 1995-1998 Honda Odyssey: 1. Remove the rear access panel located inside the van directly behind the driver’s side taillight to expose the vehicle wiring harness. 1999-2004 Honda Odyssey: 1. Open rear tailgate and remove driver’s side cargo bracket screw. 2. Carefully pull back trim panel to expose vehicle’s wiring harness. 1997-2001 Honda CR-V: 1. Remove the rear driver’s side speaker and cover. The speaker will be held in place with three screws. The vehicle connector will be secured to the pseaker wires. 2002-2006 Honda CR-V: 1. Open the rear tailgate and remove the cargo door on the floor. Remove the storage container from the vehicle floor and set aside. 2. Remove the rear threshold and driver’s side cargo bracket screw. Remove the cargo screw on the driver’s side trim panel. Remove the cargo bracket by unscrewing bolt fron vehicle floor. 3. Carefully pry trim panel away from vehicle body. -

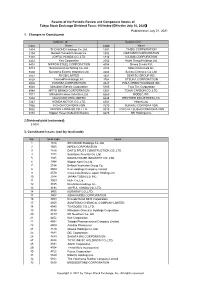

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

First Driving Behavior-Based Telematics Automobile Insurance Developed for Toyota Connected Cars in Japan

November 8, 2017 Name of Listed Company: MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings, Inc. Name of Representative: Yasuyoshi Karasawa, President & CEO (Securities Code: 8725, Tokyo Stock Exchange and Nagoya Stock Exchange) Contact: Corporate Communications and Investor Relations Dept. http://www.ms-ad-hd.com/en/ir/contact/index.html First Driving Behavior-Based Telematics Automobile Insurance Developed for Toyota Connected Cars in Japan Aioi Nissay Dowa Insurance Co., Ltd. (President: Yasuzo Kanasugi, “ADI”), a subsidiary of MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings, Inc. (President & CEO: Yasuyoshi Karasawa) announces jointly with Toyota Motor Corporation (“Toyota”) that ADI and Toyota developed the first driving behavior-based telematics automobile insurance for Toyota Connected Cars in Japan and ADI will launch in January, 2018 (Inception date of policy will be after April, 2018). Please see the details in the attachment below. - End – Attachment Toyota Motor Corporation Aioi Nissay Dowa Insurance Co., Ltd. First Driving Behavior-based Telematics Automobile Insurance Developed for Toyota Connected Cars in Japan Toyota City, Japan, November 8, 2017―Toyota Motor Corporation (Toyota) and the MS&AD Insurance Group’s Aioi Nissay Dowa Insurance Co., Ltd. (Aioi Nissay Dowa Insurance) have jointly developed Japan’s first driving behavior-based telematics automobile insurance. The plan is available to owners of certain units of Toyota connected cars*1, and uses driving data gathered via telematics*2 technologies to adjust insurance premiums based on the level of safe driving every month. Total insurance premiums comprise a combination of basic insurance premiums and usage-based insurance and, under this new plan up to 80 percent*3 of usage-based insurance premiums can be discounted. -

Corporate Brochure

Corporate Brochure Bridgestone Corporation Public Relations Department 1-1, Kyobashi 3-chome, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-8340, Japan This brochure is printed on FSC R -certified paper with vegetable oil ink. Phone: +81-3-6836-3333 It is also printed using a waterless printing process, which does not give off harmful liquids. http://www.bridgestone.com/ Published September 2014 in Japan The Bridgestone Essence Mission Serving Society with Superior Quality Foundation Heartwarming moments in a peaceful life, Seijitsu-Kyocho (Integrity and Teamwork) Shinshu-Dokuso (Creative Pioneering) Excitement at your own professional or personal growth ― Genbutsu-Genba (Decision Making Based on Verified, On-Site Observations) Every time you step forward to meet the future, Jukuryo-Danko (Decisive Action after Thorough Planning) Bridgestone will be always there with you. That is our wish. The Bridgestone Essence is derived from the company’s Mission and Foundation. In your daily life and When we talk about our Mission, In your future, we talk about the actions of our employees, who strive day after day, across the world, to achieve our shared goals, Providing you with constant support, as captured in the words of our founder. Bridgestone is always there for you. When we talk about our Foundation, we talk about the principles and values which all employees bring to their work. 2 3 The pursuit of superior quality starts here. The Bridgestone Group owns an approximately 24,000-hectare rubber estate in Indonesia as well as an approximately 48,000-hectare rubber estate in Liberia. The plantations at both of these sites yield rubber sap that we extract and process. -

Honda Civic Vs Toyota Corolla

Family Hatchback Comparison: Honda Civic Vs Toyota Corolla If we list out some of the best selling cars around the world, both the Honda Civic and Toyota Corolla usually top it, selling millions of examples annually. Around 300,000 Civics were sold last year in the U.S alone, followed by the Corolla at 250,000. While both of them promise simple motoring for an affordable price, there are some considerable differences between the two. So which is the better choice? Here, let’s take a look at the differences between the two and help you choose your next family hatchback. If you are looking for top hatchbacks for sale, these two can be relied upon with closed eyes. today just like their sedan counterparts. Unlike the Toyota Corolla which received a redesign back in 2018, the Honda Civic is all-new for 2022 with a redesigned body, updated interiors, and a longer feature list. Fortunately, it still balances ride and handling exceptionally well. The new Civic is only available in both sedan and hatchback body styles, as the coupe is discontinued due to low sales. We can expect the new Civic Hatchback to reach showrooms later in 2021, and it will be built in the U.S, unlike the previous generation. This time around, Honda has given the Hatchback a much sportier design to attract younger buyers. On the flip side, the Toyota Corolla remains mostly unchanged since the latest generation was launched in 2018. Unlike the Civic, the Corolla is the more affordable option here with many more features, and also has Toyota’s legendary reliability on its side. -

Service and Parts Are Now Open Every Tuesday Night Until 7 Pm

SCHWARTZ MAZDA SEPTEMBER 2019 BOOKMARK & SHARE: SERVICE AND PARTS ARE NOW OPEN EVERY TUESDAY NIGHT UNTIL 7 PM Send our Family-Size Fun: 2019 Mazda CX-9 coupons Signature Review directly to your mobile phone! If you’re looking for a ____________________ three-row crossover Schwartz Mazda that isn’t just a Service Specials! wannabe minivan, then the 2019 Mazda CX-9 should be at the top of your list; the same holds true for any of Mazda’s ________________________________ current crossovers. As fun as the CX-3 __________________ and CX-5 are, though, the CX-9 is fun Heritage, Experience = Dealership Homepage on a family scale, and the 2019 Mazda Schwartz Mazda New Vehicles CX-9 gets even better with a quieter, Experience 100 Years of Pre-Owned Vehicles refined interior and a retuned Schwartz Mazda History on Specials suspension. Like all other Mazda YouTube Parts vehicles, the 2019 Mazda CX-9 comes _____________________________ Service in Sport, Touring and Grand Touring MAZDA TO PARTNER WITH Lease & Finance trim levels. And the Signature trim is the TOYOTA FINANCIAL SERVICES Truck Center luxury model. Mazda has been using JPMorgan Chase About Us as its financial arm under the Mazda Hours & Directions Mazda designers have done an Capital Services name for the past Contact Us excellent job creating a brand image – decade. But __________________ called KODO, Soul of Motion – that starting April 1, CONTENTS surpasses vehicle size with lines and 2020, Mazda Motor proportions that look good on of America Inc. will • 2019 Mazda CX-9 everything from the smallest CX-3 to be switching to this family-sized CX-9. -

Toyota, Suzuki to Work Together in Green, Safety Technology 6 February 2017, by Yuri Kageyama

Toyota, Suzuki to work together in green, safety technology 6 February 2017, by Yuri Kageyama other with products and components. The next step would be to come up with specific cooperation projects, they said. Suzuki does not have a hybrid, electric car or fuel cell vehicle in its lineup. Self-driving cars are also a growing focus in the industry. Toyota President Akio Toyoda praised Suzuki's pioneer spirit. "I am truly thankful for having been given this opportunity to work together with a company such as Suzuki, which overflows with the spirit of In this Oct. 12, 2016 file photo, Toyota Motor Corp. challenge. Toyota looks forward to learning much," President Akio Toyoda, left, speaks with Suzuki Motor he said in a statement. Corp. Chairman Osamu Suzuki during a news conference in Tokyo. Japanese automakers Toyota and Developing futuristic technology is costly, and the Suzuki, which began looking into a partnership in automakers can hope to reduce costs by working October, say they have decided to work together in together. Toyota and Suzuki have encouraged ecological and safety technology—a rapidly growing area others to join the partnership. in the industry. Toyota Motor Corp., the maker of the Camry sedan, Prius hybrid and Lexus luxury models, "We now stand at the starting point for building a and Suzuki Motor Corp., which specializes in tiny cars, announced the decision Monday, Feb. 6, 2017, following concrete cooperative relationship. I want to give approval by the company boards. (Shigeyuki this effort our fullest and to aim at producing results Inakuma/Kyodo News via AP, File) that will lead Toyota to conclude that it was the right thing for Toyota to have decided to work together with Suzuki," said Suzuki Chairman Osamu Suzuki. -

Mazda Toyota Manufacturing, USA, Inc

March 9. 2018 (March 8, 2018 - CST) Mazda Motor Corporation Toyota Motor Corporation Mazda and Toyota Establish Joint-Venture Company “Mazda Toyota Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc.” - Vehicle assembly plant with annual production capacity of 300,000 units will be built in Huntsville, Alabama. - Investment to reach $1.6 billion for facility that will employ up to 4,000, open in 2021 Huntsville, Alabama, U.S.A. (March 8, 2018) / Hiroshima and Toyota-city, Japan (March 9, 2018) – Mazda Motor Corporation and Toyota Motor Corporation have established their new joint- venture company “Mazda Toyota Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc.” (MTMUS) that will produce vehicles in Huntsville, Alabama starting in 2021. The new plant will have the capacity to produce 150,000 units of Mazda’s crossover model that will be newly introduced to the North American market and 150,000 units of the Toyota Corolla. The facility is expected to create up to 4,000 jobs. Toyota and Mazda are investing $1.6 billion towards this project with equal funding contributions. “We hope to make MTMUS a plant that will hold a special place in the heart of the local community for many, many years,” said Mazda’s Executive Officer Masashi Aihara, who will serve as President of MTMUS. “By combining the best of our technologies and corporate cultures, Mazda and Toyota will not only produce high-quality cars but also create a plant employees will be proud to work at and contribute to the further development of the local economy and the automotive industry. We hope that cars made at the new plant will enrich the lives of their owners and become much more than just a means of transportation.” “The new plant, which will be Toyota’s 11th manufacturing facility in the U.S., not only represents our continuous commitment in this country, but also is a key factor in improving our competitiveness of manufacturing in the U.S.,” said Hironori Kagohashi, executive general manager of Toyota and MTMUS’s Executive Vice President.