1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lenticular Galaxy, a Bit Spiral, a Bit Elliptical

Lenticular galaxy, a bit spiral, a bit elliptical Domingos Soares Lenticular galaxies were the last to be included in the morphological classification of galaxies designed by the American astronomer Edwin Hubble (1889-1953). Morphology refers to the shapes of galaxies. The lenticular are galaxies whose stars are distributed in the form of a disk and a central spheroid, like spiral galaxies, but they do not have spiral arms. Besides, they are \clean", like elliptical galaxies, that is, they lack interstellar gas and dust, but unlike those, they do not show a global spheroidal shape. All in all, lenticular galaxies have a bit of each one of the two classes of galaxies. When Hubble put forward his classification of galaxies, for the first time, in 1926, the lenticular class was not recognized. But through the years, Hub- ble began to believe that there should be a class of galaxies that could make a bridge between ellipticals, that have the general form of a spheroid, and spiral galaxies, that are predominantly disk galaxies, with bright and majes- tic arms. In his 1936 book, \The Realm of the Nebulae", he included this class in his galaxy tunning fork. The elliptical galaxies were in the handle of the tunning fork and the spiral galaxies, with and without bars, in the two arms of the fork. In the vertex of the tunning fork, representing a morpho- logical transition between ellipticals and spirals, he postulated the existence of a new class, that of the lenticular galaxies. They were designated by the letter \S" followed by \0", that is, S0. -

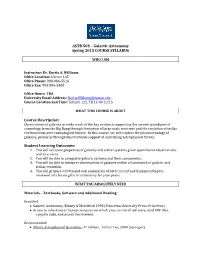

ASTR 503 – Galactic Astronomy Spring 2015 COURSE SYLLABUS

ASTR 503 – Galactic Astronomy Spring 2015 COURSE SYLLABUS WHO I AM Instructor: Dr. Kurtis A. Williams Office Location: Science 145 Office Phone: 903-886-5516 Office Fax: 903-886-5480 Office Hours: TBA University Email Address: [email protected] Course Location and Time: Science 122, TR 11:00-12:15 WHAT THIS COURSE IS ABOUT Course Description: Observations of galaxies provide much of the key evidence supporting the current paradigms of cosmology, from the Big Bang through formation of large-scale structure and the evolution of stellar environments over cosmological history. In this course, we will explore the phenomenology of galaxies, primarily through observational support of underlying astrophysical theory. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. You will calculate properties of galaxies and stellar systems given quantitative observations, and vice-versa. 2. You will be able to categorize galactic systems and their components. 3. You will be able to interpret observations of galaxies within a framework of galactic and stellar evolution. 4. You will prepare written and oral summaries of both current and fundamental peer- reviewed articles on galactic astronomy for your peers. WHAT YOU ABSOLUTELY NEED Materials – Textbooks, Software and Additional Reading: Required: • Galactic Astronomy, Binney & Merrifield 1998 (Princeton University Press: Princeton) • Access to a desktop or laptop computer on which you can install software, read PDF files, compile code, and access the internet. Recommended: • Allen’s Astrophysical Quantities, 4th Edition, Arthur Cox, 2000 (Springer) Course Prerequisites: Advanced undergraduate classical dynamics (equivalent of Phys 411) or Phys 511. HOW THE COURSE WILL WORK Instructional Methods / Activities / Assessments Assigned Readings There is far too much material in the text for us to cover every single topic in class. -

Multicolor Surface Photometry of Lenticular Galaxies

The Astronomical Journal, 129:630–646, 2005 February # 2005. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. MULTICOLOR SURFACE PHOTOMETRY OF LENTICULAR GALAXIES. I. THE DATA Sudhanshu Barway School of Studies in Physics, Pandit Ravishankar Shukla University, Raipur 492010, India; [email protected] Y. D. Mayya Instituto Nacional de Astrofisı´ca, O´ ptica y Electro´nica, Apdo. Postal 51 y 216, Luis Enrique Erro 1, 72000 Tonantzintla, Pue., Mexico; [email protected] Ajit K. Kembhavi Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Post Bag 4, Ganeshkhind, Pune 411007, India; [email protected] and S. K. Pandey1 School of Studies in Physics, Pandit Ravishankar Shukla University, Raipur 492010, India; [email protected] Receivedv 2003 Auggust 13; accepted 2004 October 20 ABSTRACT We present multicolor surface and aperture photometry in the B, V, R,andK0 bands for a sample of 34 lenticular galaxies from the Uppsala General Catalogue. From surface photometric analysis, we obtain radial profiles of surface brightness, colors, ellipticity, position angle, and the Fourier coefficients that describe the departure of isophotal shapes from a purely elliptical form; we find the presence of dust lanes, patches, and ringlike structure in several galaxies in the sample. We obtain total integrated magnitudes and colors and find that these are in good agreement with the values from the Third Reference Catalogue. Isophotal colors are correlated with each other, following the sequence expected for early-type galaxies. The color gradients in lenticular galaxies are more negative than the corresponding gradients in elliptical galaxies. There is a good correlation between BÀVand BÀR color gradients, and the mean gradients in the BÀV, BÀR,andVÀK0 colors are À0:13 Æ 0:06, À0:18 Æ 0:06, and À0:25 Æ 0:11 mag dexÀ1 in radius, respectively. -

PHYS 1302 Intro to Stellar & Galactic Astronomy

PHYS 1302: Introduction to Stellar and Galactic Astronomy University of Houston-Downtown Course Prefix, Number, and Title: PHYS 1302: Introduction to Stellar and Galactic Astronomy Credits/Lecture/Lab Hours: 3/2/2 Foundational Component Area: Life and Physical Sciences Prerequisites: Credit or enrollment in MATH 1301 or MATH 1310 Co-requisites: None Course Description: An integrated lecture/laboratory course for non-science majors. This course surveys stellar and galactic systems, the evolution and properties of stars, galaxies, clusters of galaxies, the properties of interstellar matter, cosmology and the effort to find extraterrestrial life. Competing theories that address recent discoveries are discussed. The role of technology in space sciences, the spin-offs and implications of such are presented. Visual observations and laboratory exercises illustrating various techniques in astronomy are integrated into the course. Recent results obtained by NASA and other agencies are introduced. Up to three evening observing sessions are required for this course, one of which will take place off-campus at George Observatory at Brazos Bend State Park. TCCNS Number: N/A Demonstration of Core Objectives within the Course: Assigned Core Learning Outcome Instructional strategy or content Method by which students’ Objective Students will be able to: used to achieve the outcome mastery of this outcome will be evaluated Critical Thinking Utilize scientific Star Property Correlations – They will be instructed to processes to identify students will form and test prioritize these properties in Empirical & questions pertaining to hypotheses to explain the terms of their relevance in Quantitative natural phenomena. correlation between a number of deciding between competing Reasoning properties seen in stars. -

Galactic Astronomy with AO: Nearby Star Clusters and Moving Groups

Galactic astronomy with AO: Nearby star clusters and moving groups T. J. Davidgea aDominion Astrophysical Observatory, Victoria, BC Canada ABSTRACT Observations of Galactic star clusters and objects in nearby moving groups recorded with Adaptive Optics (AO) systems on Gemini South are discussed. These include observations of open and globular clusters with the GeMS system, and high Strehl L observations of the moving group member Sirius obtained with NICI. The latter data 2 fail to reveal a brown dwarf companion with a mass ≥ 0.02M in an 18 × 18 arcsec area around Sirius A. Potential future directions for AO studies of nearby star clusters and groups with systems on large telescopes are also presented. Keywords: Adaptive optics, Open clusters: individual (Haffner 16, NGC 3105), Globular Clusters: individual (NGC 1851), stars: individual (Sirius) 1. STAR CLUSTERS AND THE GALAXY Deep surveys of star-forming regions have revealed that stars do not form in isolation, but instead form in clusters or loose groups (e.g. Ref. 25). This is a somewhat surprising result given that most stars in the Galaxy and nearby galaxies are not seen to be in obvious clusters (e.g. Ref. 31). This apparent contradiction can be reconciled if clusters tend to be short-lived. In fact, the pace of cluster destruction has been measured to be roughly an order of magnitude per decade in age (Ref. 17), indicating that the vast majority of clusters have lifespans that are only a modest fraction of the dynamical crossing-time of the Galactic disk. Clusters likely disperse in response to sudden changes in mass driven by supernovae and stellar winds (e.g. -

Dwarfs Walking in a Row the filamentary Nature of the NGC 3109 Association

A&A 559, L11 (2013) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322744 & c ESO 2013 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor Dwarfs walking in a row The filamentary nature of the NGC 3109 association M. Bellazzini1, T. Oosterloo2;3, F. Fraternali4;3, and G. Beccari5 1 INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Bologna, via Ranzani 1, 40127 Bologna, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Postbus 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands 3 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Postbus 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands 4 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia - Università degli Studi di Bologna, viale Berti Pichat 6/2, 40127 Bologna, Italy 5 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei Munchen, Germany Received 24 September 2013 / Accepted 22 October 2013 ABSTRACT We re-consider the association of dwarf galaxies around NGC 3109, whose known members were NGC 3109, Antlia, Sextans A, and Sextans B, based on a new updated list of nearby galaxies and the most recent data. We find that the original members of the NGC 3109 association, together with the recently discovered and adjacent dwarf irregular Leo P, form a very tight and elongated configuration in space. All these galaxies lie within ∼100 kpc of a line that is '1070 kpc long, from one extreme (NGC 3109) to the other (Leo P), and they show a gradient in the Local Group standard of rest velocity with a total amplitude of 43 km s−1 Mpc−1, and a rms scatter of just 16.8 km s−1. It is shown that the reported configuration is exceptional given the known dwarf galaxies in the Local Group and its surroundings. -

May 2013 BRAS Newsletter

www.brastro.org May 2013 What's in this issue: PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE .............................................................................................................................. 2 NOTES FROM THE VICE PRESIDENT ........................................................................................................... 3 MESSAGE FROM THE HRPO ...................................................................................................................... 4 OBSERVING NOTES ..................................................................................................................................... 5 DEEP SKY OBJECTS ................................................................................................................................... 6 MAY ASTRONOMICAL EVENTS .................................................................................................................... 7 TREASURER’S NOTES ................................................................................................................................. 8 PREVIOUS MEETING MINUTES .................................................................................................................... 9 IMPORTANT NOTE: This month's meeting will be held on Saturday, May 18th at LIGO. PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Hi Everyone, April was quite a busy month and the busiest day was International Astronomy Day. As you may have heard, we had the highest attendance at our Astronomy Day festivities at the HRPO ever. Approximately 770 people attended this year -

Galaxies: Outstanding Problems and Instrumental Prospects for the Coming Decade (A Review)* T (Cosmology/History of Astronomy/Quasars/Space) JEREMIAH P

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 74, No. 5, pp. 1767-1774, May 1977 Astronomy Galaxies: Outstanding problems and instrumental prospects for the coming decade (A Review)* t (cosmology/history of astronomy/quasars/space) JEREMIAH P. OSTRIKER Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 Contributed by Jeremiah P. Ostriker, February 3, 1977 ABSTRACT After a review of the discovery of external It is more than a little astonishing that in the early part of this galaxies and the early classification of these enormous aggre- century it was the prevailing scientific view that man lived in gates of stars into visually recognizable types, a new classifi- a universe centered about himself; by 1920 the sun's newly cation scheme is suggested based on a measurable physical quantity, the luminosity of the spheroidal component. It is ar- discovered, slightly off-center position was still controversial. gued that the new one-parameter scheme may correlate well The discovery was, ironically, due to Shapley. both with existing descriptive labels and with underlying A little background to this debate may be useful. The Island physical reality. Universe hypothesis was not new, having been proposed 170 Two particular problems in extragalactic research are isolated years previously by the English astronomer, Thomas Wright as currently most fundamental. (i) A significant fraction of the (2), and developed with remarkably prescience by Emmanuel energy emitted by active galaxies (approximately 1% of all galaxies) is emitted by very small central regions largely in parts Kant, who wrote (see refs. 10 and 23 in ref. 3) in 1755 (in a of the spectrum (microwave, infrared, ultraviolet and x-ray translation from Edwin Hubble). -

Observational Cosmology - 30H Course 218.163.109.230 Et Al

Observational cosmology - 30h course 218.163.109.230 et al. (2004–2014) PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 31 Oct 2013 03:42:03 UTC Contents Articles Observational cosmology 1 Observations: expansion, nucleosynthesis, CMB 5 Redshift 5 Hubble's law 19 Metric expansion of space 29 Big Bang nucleosynthesis 41 Cosmic microwave background 47 Hot big bang model 58 Friedmann equations 58 Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric 62 Distance measures (cosmology) 68 Observations: up to 10 Gpc/h 71 Observable universe 71 Structure formation 82 Galaxy formation and evolution 88 Quasar 93 Active galactic nucleus 99 Galaxy filament 106 Phenomenological model: LambdaCDM + MOND 111 Lambda-CDM model 111 Inflation (cosmology) 116 Modified Newtonian dynamics 129 Towards a physical model 137 Shape of the universe 137 Inhomogeneous cosmology 143 Back-reaction 144 References Article Sources and Contributors 145 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 148 Article Licenses License 150 Observational cosmology 1 Observational cosmology Observational cosmology is the study of the structure, the evolution and the origin of the universe through observation, using instruments such as telescopes and cosmic ray detectors. Early observations The science of physical cosmology as it is practiced today had its subject material defined in the years following the Shapley-Curtis debate when it was determined that the universe had a larger scale than the Milky Way galaxy. This was precipitated by observations that established the size and the dynamics of the cosmos that could be explained by Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. -

TEACHER GUIDE Get Close to Mcdonald Observatory

TEACHER GUIDE Get Close to McDonald Observatory Live and in Person Live for Students McDonald Observatory offers a unique set- The Frank N. Bash Visitors Center features ting for teacher workshops: the Observatory a full classroom, 90-seat theater, astronomy and Visitors Center in the Davis Mountains park with telescopes, and an exhibit hall of West Texas. The workshops offer inquiry- for groups of 12 to 100 students. These based activities aligned with national and programs offer hands-on, inquiry-based ac- Texas science and math standards. Teachers tivities in an engaging environment, provid- can practice their new astronomy skills under ing an informal extension to classroom and the dark West Texas skies, and partner with science instruction. Reservations are recom- trained and nationally recognized astronomy mended at least six weeks in advance. educators. mcdonaldobservatory.org/teachers/visit mcdonaldobservatory.org/teachers/profdev Live on Video Visit McDonald Observatory from the class- room through an interactive videoconference program, “Live! From McDonald Observato- ry.” The live 50-minute program is designed for Texas classrooms, with versions for grades 3-5, 6-8, and 9-12. Each program is aligned with Texas education standards. mcdonaldobservatory.org/lfmo IOLO (INSET) C RANK CIAN F ; ; D For complete details BENNINGFIEL 432-426-3640 D mcdonaldobservatory.org/teachers DAMON Table of Contents TEACHER GUIDE To the Teacher 4 Resources 38 5th Edition Staff Classroom Activities EXECUTIVE EDITOR Damond Benningfield EDITOR Rebecca Johnson Shadow Play 6 K-4 ART DIRECTOR Tim Jones CURRICULUM SPECIALISTS Dr. Mary Kay Hemenway Kyle Fricke Brad Armosky RADES CIRCULATION MANAGER Paul Previte G DIRECTOR, PUBLIC INFORMATION Sandra Preston Modeling the Night Sky 8 Special thanks to all the teachers who evaluated this guide. -

Understanding Lenticular Galaxy Formation Via Extended Stellar Kinematics

galaxies Conference Report The SLUGGS Survey: Understanding Lenticular Galaxy Formation via Extended Stellar Kinematics Sabine Bellstedt Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn 3122, Melbourne, Australia; [email protected] Academic Editors: Duncan A. Forbes and Ericson D. Lopez Received: 4 May 2017; Accepted: 26 May 2017; Published: 30 May 2017 Abstract: We present the latest published and preliminary results from the SLUGGS Survey discussing the formation of lenticular galaxies through analysis of their kinematics. These include a comparison of the measured stellar spin of low-mass lenticular galaxies to the spin of remnant galaxies formed by binary merger simulations to assess whether a merger is a likely formation mechanism for these galaxies. We determine that while a portion of lenticular galaxies have properties consistent with these remnants, others are not, indicating that they are likely “faded spirals”. We also present a modified version of the spin–ellipticity diagram, which utilises radial tracks to be able to identify galaxies with intermediate-scale discs. Such galaxies often have conflicting morphological classifications, depending on whether photometric or kinematic measurements are used. Finally, we present preliminary results on the total mass density profile slopes of lenticular galaxies to assess trends as lower stellar masses are probed. Keywords: galaxies: formation; galaxies: evolution; galaxies: elliptical and lenticular 1. Introduction Lenticular galaxies share similarities with both elliptical galaxies (in that they are quenched systems) and spiral galaxies (in that many lenticular galaxies have large-scale discs). The manner in which these systems form is still not entirely understood, and it is likely that multiple processes contribute to their formation. -

Aaron J. Romanowsky Curriculum Vitae (Rev. 1 Septembert 2021) Contact Information: Department of Physics & Astronomy San

Aaron J. Romanowsky Curriculum Vitae (Rev. 1 Septembert 2021) Contact information: Department of Physics & Astronomy +1-408-924-5225 (office) San Jose´ State University +1-409-924-2917 (FAX) One Washington Square [email protected] San Jose, CA 95192 U.S.A. http://www.sjsu.edu/people/aaron.romanowsky/ University of California Observatories +1-831-459-3840 (office) 1156 High Street +1-831-426-3115 (FAX) Santa Cruz, CA 95064 [email protected] U.S.A. http://www.ucolick.org/%7Eromanow/ Main research interests: galaxy formation and dynamics – dark matter – star clusters Education: Ph.D. Astronomy, Harvard University Nov. 1999 supervisor: Christopher Kochanek, “The Structure and Dynamics of Galaxies” M.A. Astronomy, Harvard University June 1996 B.S. Physics with High Honors, June 1994 College of Creative Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara Employment: Professor, Department of Physics & Astronomy, Aug. 2020 – present San Jose´ State University Associate Professor, Department of Physics & Astronomy, Aug. 2016 – Aug. 2020 San Jose´ State University Assistant Professor, Department of Physics & Astronomy, Aug. 2012 – Aug. 2016 San Jose´ State University Research Associate, University of California Observatories, Santa Cruz Oct. 2012 – present Associate Specialist, University of California Observatories, Santa Cruz July 2007 – Sep. 2012 Researcher in Astronomy, Department of Physics, Oct. 2004 – June 2007 University of Concepcion´ Visiting Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Astronomical and May 2005 Geophysical Sciences, National University of La Plata Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Physics and Astronomy, June 2002 – Oct. 2004 University of Nottingham Postdoctoral Fellow, Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, Oct. 1999 – May 2002 Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Research Fellow, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics June 1994 – Oct.