Background of Abraham Lincoln's Lyceum Address the Murder Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Confession of George Atzerodt

The Confession of George Atzerodt Full Transcript (below) with Introduction George Atzerodt was a homeless German immigrant who performed errands for the actor, John Wilkes Booth, while also odd-jobbing around Southern Maryland. He had been arrested on April 20, 1865, six days after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth. Booth had another errand boy, a simpleton named David Herold, who resided in town. Herold and Atzerodt ran errands for Booth, such as tending horses, delivering messages, and fetching supplies. Both were known for running their mouths, and Atzerodt was known for drinking. Four weeks before the assassination, Booth had intentions to kidnap President Lincoln, but when his kidnapping accomplices learned how ridiculous his plan was, they abandoned him and returned to their homes in the Baltimore area. On the day of the assassination the only persons remaining in D.C. who had any connection to the kidnapping plot were Booth's errand boys, George Atzerodt and David Herold, plus one of the key collaborators with Booth, James Donaldson. After David Herold had been arrested, he confessed to Judge Advocate John Bingham on April 27 that Booth and his associates had intended to kill not only Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, but Vice President Andrew Johnson as well. David Herold stated Booth told him there were 35 people in Washington colluding in the assassination. This information Herold learned from Booth while accompanying him on his flight after the assassination. In Atzerodt's confession, this band of assassins was described as a crowd from New York. -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production. -

National Mall & Memorial Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS NATIONAL MALL & MEMORIAL PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. BLEED AREA TRIM SIZE WELCOME LIVE AREA Welcome to our nation’s capital, Wash- return trips for you and your family. Save it ington, District of Columbia! as a memento or pass it along to friends. Zion National Park Washington, D.C., is rich in culture and The National Park Service, along with is the result of erosion, history and, with so many sites to see, Eastern National, the Trust for the National sedimentary uplift, and there are countless ways to experience Mall and Guest Services, work together this special place. As with all American to provide the best experience possible Stephanie Shinmachi. Park Network editions, this guide to the for visitors to the National Mall & Me- 8 ⅞ National Mall & Memorial Parks provides morial Parks. information to make your visit more fun, memorable, safe and educational. -

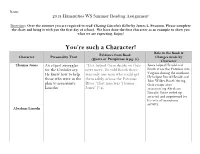

You're Such a Character!

Name:_____________________________________________ 2018 Humanities WS Summer Reading Assignment Directions: Over the summer you are required to read Chasing Lincoln’s Killer by James L. Swanson. Please complete the chart and bring it with you the first day of school. We have done the first character as an example to show you what we are expecting. Enjoy! You’re such a Character! Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Thomas Jones An expert smuggler “Cox helped them decide on their Jones helped Herold and for the Confederacy. next move. He told Booth there Booth cross the Potomac into He knew how to help was only one man who could get Virginia during the manhunt. those who were in the them safely across the Potomac He helped David Herold and John Wilkes Booth during plan to assassinate River. That man was Thomas their escape after Lincoln. Jones” (74). assassinating Abraham Lincoln. Jones ended up arrested and imprisoned for his acts of treasonous activity. Abraham Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Wilkes Booth Edwin Stanton George Atzerodt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Garrett John Surratt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Mary Surratt Mary Todd Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. -

Mary Surratt: the Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita History Class Publications Department of History 2013 Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Leah, "Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death" (2013). History Class Publications. 34. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history/34 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Surratt: The Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson 1 On the night of April 14th, 1865, a gunshot was heard in the balcony of Ford’s Theatre followed by women screaming. A shadowy figure jumped onto the stage and yelled three now-famous words, “Sic semper tyrannis!” which means, “Ever thus to the tyrants!”1 He then limped off the stage, jumped on a horse that was being kept for him at the back of the theatre, and rode off into the moonlight with an unidentified companion. A few hours later, a knock was heard on the door of the Surratt boarding house. The police were tracking down John Wilkes Booth and his associate, John Surratt, and they had come to the boarding house because it was the home of John Surratt. An older woman answered the door and told the police that her son, John Surratt, was not at home and she did not know where he was. -

Hatching Execution: Andrew Johnson and the Hanging of Mary Surratt

Hatching Execution: Andrew Johnson and the Hanging of Mary Surratt Sarah Westad History 489: Research Seminar December 2015 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Contents Abstract iii Figures iv Introduction 1 Historiography 10 Primary Source Analysis 22 Conclusion 33 Works Cited 35 ii Abstract In 1865, the American Civil War and the assassination of US President Abraham Lincoln plunged the country into a state of panic. Federal officials quickly took to the ranks, imprisoning hundreds of suspected rebels believed to be involved in the assassination. Ultimately, only eight individuals, dubbed conspirators, were prosecuted and charged with murdering the Commander- in-Chief. During their trials, new president Andrew Johnson voiced grave concern over one particular conspirator, middle-aged Catholic widow Mary Surratt. As the mother of escaped conspirator, John Surratt, Johnson viewed Mrs. Surratt as an individual that needed to be treated with a particular urgency, resulting in a series of events that led to Mrs. Surratt’s execution, less than three months after the assassination, on July 7, 1865. This paper analyzes the actions of Johnson and considers the American public’s responses to Mary Surratt’s hanging. Additionally, this paper looks at the later writings of Andrew Johnson in order to gain an understanding of his feelings on Mrs. Surratt in the weeks, months, and years after her execution, as well as -

The Circuit Chautauqua in Nebraska, 1904-1924

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Culture as Entertainment: The Circuit Chautauqua in Nebraska, 1904-1924 Full Citation: James P Eckman, “Culture as Entertainment: The Circuit Chautauqua in Nebraska, 1904-1924,” Nebraska History 75 (1994): 244-253 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1994Chautauqua.pdf Date: 8/09/2013 Article Summary: At first independent Chautauqua assemblies provided instruction. The later summer circuit Chautauquas sought primarily to entertain their audiences. Cataloging Information: Names: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Keith Vawter, Russell H Conwell, William Jennings Bryan, Billy Sunday Sites of Nebraska Chautauquas: Kimball, Alma, Homer, Kearney, Pierce, Fremont, Grand Island, Lincoln, Fullerton Keywords: lyceum, Redpath Bureau, Keith Vawter, contract guarantee, “tight booking,” Nebraska Epworth Assembly (Lincoln), Chautauqua Park Association (Fullerton), -

Dr. Charles Leale

The Lincoln Assassination: Facts, Fiction and Frankly Craziness Class 2 – Dramatis personae Jim Dunphy [email protected] 1 Intro In this class, we will look at 20+ people involved in the Lincoln Assassination, both before the event and their eventual fates. 2 Intro 1. In the Box 2. Conspirators 3. At the theater 4. Booth Escape 5. Garrett Farm 3 In the Box 4 Mary Lincoln • Born in Kentucky, she was a southern belle. • Her sister was married to Ben Helm, a Confederate General killed at the battle of Chickamauga • She knew tragedy in her life as two sons died young, one during her time as First Lady • She also had extravagant tastes, and was under repeated investigation for her redecorating the White House 5 Mary Lincoln • She was also fiercely protective of her position as First Lady, and jealous of anyone she saw as a political or romantic rival • When late to a review near the end of the war and saw Lincoln riding with the wife of General Ord, she reduced Mrs. Ord to tears 6 Mary Lincoln • Later that day, Mrs.. Lincoln asked Julia Dent Grant, the wife of General Grant “I suppose you’ll get to the White House yourself, don’t you?” • When Mrs. Grant told her she was happy where she was, Mrs. Lincoln replied “Oh, you better take it if you can get it!” • As a result of these actions, Mrs.. Grant got the General to decline an invitation to accompany the Lincolns to Ford’s Theater 7 Mary Lincoln • After Lincoln was shot and moved to the Peterson House, Mrs. -

The Cover-Up of Booth's Unknown Accomplices

The Cover-up of Booth’s Unknown Accomplices By Don Thomas Who was Charles Lee and what happened to him? On Maryland’s Eastern Shore, April 16, 1865, Charles Lee became the first conspirator captured as an accomplice to John Wilkes Booth. He was also a U. S. Government employee. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and his military investigators covered up many implicated suspects during the Lincoln conspiracy investigation but Charles Lee was the first. The motive to have so many War Department secrets was twofold. Had any government employees been convicted in Booth’s plot against Lincoln, such Federal accomplices would have exposed the actual Washington conspiracy to remove the President from office by assassination. Federal accomplices would also destroy Stanton’s assertion that Lincoln’s murder was a Richmond plot. The War Department investigators were provided total control over all the collected evidence and could easily cover-up anything that would expose a Washington conspiracy. They were all Federal officers under Stanton and they had only two choices: honestly reveal their collected evidence which would expose a military coup, or support Stanton’s declaration against Richmond. George Atzerodt was the seventh conspirator arrested on April 20th, four days after the arrest of Charles Lee. During Atzerodt’s last interrogation, he implicated many unpublicized Federal, as well as New York accomplices plotting with Booth, even conspirators he referred to as friends of the President. On May 1, 1865, George Atzerodt further implicated Charles Lee when he told the military Marshal of Baltimore, James McPhail (in his thick German accent) that a man named Charles “Laytz” was to row Booth, all his kidnappers and the President across the river into Virginia. -

The Lincoln Assassination Connection

The Lincoln Assassination Connection Germantown's link to the assassination of President Lincoln Germantown, MD By SUSAN SODERBERG April 23, 2011 Many of you who have seen the recent movie The Conspirator will know that George Andrew Atzerodt (alias Andrew Atwood), was one of the Lincoln assassination conspirators executed on July 7, 1865. Atzerodt was arrested in Germantown, the town where he had spent many years as a boy. How he got involved with the Booth gang and why he ended up back in Germantown is a compelling story. This story begins in 1844 when Atzerodt, age 9, arrives in Germantown with his family, immigrants from Prussia. His father, Henry Atzerodt, purchased land with his brother- in-law, Johann Richter, and together they built a house on Schaeffer Road. In the mid- 1850s, Henry sold his interest in the farm and moved to Westmoreland County, Va., where he operated a blacksmith shop until his untimely death around 1858. At this time Atzerodt and his brother John opened a carriage painting business in Port Tobacco, Md. After the Civil War broke out the carriage painting business was not doing well, so John went up to Baltimore and got employment as a detective with the State Provost Marshal's office. Atzerodt stayed on at Port Tobacco, but his main business was not painting carriages, it was blockade running and smuggling across the Potomac River. It was on one of these clandestine trips that he met John Surratt, son of Mary Surratt, who was acting as a courier for Confederate mail. In November 1864 Surratt convinced Atzerodt to join the group, led by John Wilkes Booth, planning to capture President Lincoln, take him to the South and hold him for ransom. -

Fitz Hugh Lane, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and the Gloucester Lyceum Author(S): Mary Foley Source: American Art Journal, Vol

Fitz Hugh Lane, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and the Gloucester Lyceum Author(s): Mary Foley Source: American Art Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1/2 (1995/1996), pp. 99-101 Published by: Kennedy Galleries, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1594607 Accessed: 30-04-2015 17:51 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1594607?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Galleries, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Art Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Thu, 30 Apr 2015 17:51:29 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions NEW DISCOVERIES IN AMERICAN ART FITZ HUGH LANE, Fig. 1. Announcementof RALPH WALDO EMERSON, the "Twenty-firstCourse AND THE 'GLOUCESTERLYCEUM. of exercises" commencing thisin- GLOUCESTER LYCEUM The Twenty-firstCoarse fexercises before before the Gloucester slitutionwill commence daring the latter part of the Lyceum in November of presentmonth The Directorshave madearrange- 1850. -

Emotions After the Assassination by Bart Brewer

Emotions after the Assassination by Bart Brewer Students will examine several photos of the four conspirators before and after execution. Students will speculate on the emotions of the conspirators shown through pictures. --- Overview------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Objectives: After completing the activity, students will be able to: • Use deduction and photo analysis to make judgments. • Be able to put thoughts onto paper and express emotions of their person. Understanding Students will be able to analyze and interpret pictures of historic Goal: significance. They will also be able to communicate effectively to a specific audience. Investigative How do events and individuals shape and develop the history of Question: Illinois and the United States? Time Required: One 45-minute class period Grade Level: 6 - 8 Topic: Presidents, Law, War, Military, Government Era: Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861 - 1877 Illinois Learning Social Studies: 16A, 16B, 16D Standards: Language Arts: 3A, 3B, 3C For information on specific Illinois Learning Standards go to www.isbe.state.il.us/ils/ +++Preparation++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Background Student’s background for this lesson will involve Civil War for Lesson: knowledge and Lincoln facts. This lesson will come at the end of the Civil War Unit just before the Civil War Test. Library of Congress Items: Title: Washington Navy Yard, D.C. David E. Herold, a conspirator Collection or Exhibit Prints and Photographs Media Type: Picture URL: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?pp/ils:@filreq(@field (NUMBER+@band(cwp+4a40212))+@field(COLLID+cwp)) Title: Washington Navy Yard, D.C. George A. Atzerodt, a conspirator Collection or Exhibit Prints and Photographs Media Type: Picture URL: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?pp/ils:@filreq(@field (NUMBER+@band(cwp+4a40210))+@field(COLLID+cwp)) Title: Washington, D.C.