Darts, Ethnicity and Dimorphism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SM-Liiga Saatiin Päätökseen Tulevaisuudesta

SM-liiga saatiin päätökseen Tulevaisuudesta retkieväin ei ole eikä sitä hallituksen nykyi- lutuksia ja muita häiriötekijöitä. Helpottaa sellä kokoonpanolla saada ikinä aikaan. Ei kaikkien kisaan osallistuvien päivää. hallituksen itse sitä ajatushautomoa tarvitse käydä läpi, vaan hoitaa sekin puoli omista Kilpailuiden pituus velvollisuuksistaan liitoa kohtaan. Kisapäivät alkavat olla liian pitkiä niin pe- Siksi syksyn kokouksessa on ensiarvoi- laajien kuin kisajärjestäjien kannalta. 12- sen tärkeää, että mukaan tulisi joku, jol- 14 tuntia on työ- tai kisapäivän pituudeksi la on aikaa ottaa tämä sarka hoitaakseen. aivan liikaa huonoilla yöunilla. Pelipäiväs- Oma näkemykseni on että hän ei saa olla sä saisi olla vain yksi pääsarja ja mahdolli- puheenjohtaja, koska olemme vahvasti pj- set B- sekä ikäkausisarjat. vetoinen liitto käytännön tasolla. Valitta- Jos kisamaksu on 35 euroa sisältäen pää- va puheenjohtaja joutuu tekemään paljon sarjan ja B-kisan, joka olisi 1. ja 2. kierrok- rutiiniasioita eikä silloin ole aikaa kehitel- sen pudonneille, niin yhdessä ennakkoil- lä uusia kuvioita. moittautumisen ja kisan aikataulutuksen Tietynlainen kylähullu ja Pelle Peloton kanssa koko kisapaketista saadaan paketti, tarvitaan hallituksen jäsenen asemassa rik- joka toimisi omaan tahtiinsa eikä rasittaisi Risto Spora komaan tuttuja latuja. Annetaan hänelle pelaajia eikä toimitsijoita. valtuudet miettiä uutta tapaa lähestyä tä- Ja kun meillä on käytössä ennakkoil- tä yksinkertaista lajia monikulmasta jopa moittautuminen, niin 1. kierroksen pudon- kierteellä nurkan takaa. nut näkee kaaviosta mihin kohtaa pääkisan Viime lehden jälkeen olin jo Huolestuttavaa on, ettei puheenjohta- po. ottelun hävinnyt menee ja tietää näin ajatellut että tämä nyt käsissä- juudesta ole käyty minkäänlaista keskuste- heti koska pelaa ”Looser Cupin” ottelunsa. si oleva lehti on viimeinen jon- lua viime vuosina. -

Darts Quiz Questions

Darts Big Quiz So, you think you know Darts? Here is a list of question for the dart related questions, how many can you get correct? written by David King QUESTIONS (MULTIPLE CHOICE) 1) Where was the first BDO World Champions held? A. Lakeside B. Alexandra Palace C. Heart of Midlands Club D. Jollees Club, Stoke-on-Trent 2) Name the three darts players who have received an MBE? A. Bristow, Lowe, Taylor B. Bristow, Gulliver, Lowe C. Ashton, Bristow, George D. Wilson, Taylor, Priestley 3) Which dart player walks onto ‘I’m too sexy’ by Right Said Fred? A. Andy Fordham B. Devon Peterson C. Deta Hedman D. Steve Beaton 4) What is Dennis Nilsson’s nickname? A. The Sheriff B. Rocky C. Excalibur D. Iron Man 5) Who had the first 100 plus televised average score? A. Eric Bristow B. John Lowe C. Keith Deller D. Phil Taylor 6) Over the last 100 years, dartboards have been commercially made and sold using four different types of material. Excluding, the plastic used in the construction of soft-tip dartboards can you name four? A. wood, clay, paper, sisal B. straw, paper, wood, pig bristle C. horse hair, wood, straw, pig bristle D. cotton, MDF, foam, compressed fur 7) What is the highest three-dart average that can be scored in a single leg of 501 double finish? A. 132 B. 147 C. 152 D. 167 8) James Wade holds a World record for hitting the most inner and outer bullseyes in 60 seconds on a standard dartboard, throwing from a normal oche length 2.37M. -

England Open 2019 - Ladies Singles 15/06/2019 09/06/2019 23:17:12

England Open 2019 - Ladies Singles 15/06/2019 09/06/2019 23:17:12 Last 256 - Best of 7 legs 1 GROUP 1 1)Lisa Ashton-LAN Last 128 - Best of 7 legs bye 129 1)Lisa Ashton-LAN 2 Diane Nash-CAM Last 64 - Best of 7 legs Suzan Konings-NL 193 3 Sarah-Louise Mallott-BUC bye 130 Sarah-Louise Mallott-BUC Tracey Cunningham-LAN 4 Tracey Cunningham-LAN Last 32 - Best of 7 legs bye 225 5 Sarah Roberts-WES bye 131 Sarah Roberts-WES Kerry Jobson-NOR 6 Kerry Jobson-NOR bye 194 7 Wendy Reinstadtler-SUR bye 132 Wendy Reinstadtler-SUR 8 Sharon McMahon-HER Sharon McMahon-HER Last 16 - Best of 7 legs bye 241 9 Rachel Bidgway-WIL bye 133 Rachel Bidgway-WIL Leanne Peetoom-ESS 10 Leanne Peetoom-ESS bye 195 11 Chloe McKivett-WAR bye 134 Chloe McKivett-WAR Jane Monaghan-HAM 12 Jane Monaghan-HAM bye 226 13 Lisa Hughes-DEV bye 135 Lisa Hughes-DEV Lisa Brosnan-MID 14 Lisa Brosnan-MID bye 196 15 Jules James-BER bye 136 Jules James-BER GROUP WINNER 16)Kirsty Hutchinson-COD 16 16)Kirsty Hutchinson-COD bye Roger Boyesen 2005-2019 http://www.dartsforwindows.com - Darts for Windows v.2.9.3.1 Page 1 England Open 2019 - Ladies Singles 15/06/2019 09/06/2019 23:17:12 Last 256 - Best of 7 legs 17 GROUP 2 9)Maria O'Brien-DEV Last 128 - Best of 7 legs bye 137 9)Maria O'Brien-DEV 18 Mandy Pawley-SUR Last 64 - Best of 7 legs Heather Lodge-LIN 197 19 Natalie Gilbert-WAR bye 138 Natalie Gilbert-WAR Jo Locke-SUF 20 Jo Locke-SUF Last 32 - Best of 7 legs bye 227 21 Michelle Lydiate-BED bye 139 Michelle Lydiate-BED Julie Lambie-LIN 22 Julie Lambie-LIN bye 198 23 Chloe O'Brien-SCO bye 140 -

Malta-Open-2017-Ladies-Singles-Final

The Finals - MALTA DARTS OPEN 2017 - Ladies Singles 15/11/2017 17/11/2017 09:55:04 Last 32 - Best of 5 legs FINALS 1)Deta Hedman-ENG 3 Last 16 - Best of 7 legs Giota Sfakioti-GRE 0 1)Deta Hedman-ENG 4 Gabriele Behrens-GER 0 Gabriele Behrens-GER 3 Quarter-finals - Best of 7 legs Debbie McBride-SCO 1 1)Deta Hedman-ENG 4 Jane Baggley Agius-MLT 1 8)Maret Liiri-FIN 0 Pat Coulson-ENG 3 Pat Coulson-ENG 1 8)Maret Liiri-FIN 4 Suzanne Price-WAL 0 Semi-finals - Best of 7 legs 8)Maret Liiri-FIN 3 1)Deta Hedman-ENG 4 5)Fallon Sherrock-ENG 3 4)Corrine Hammond-AUS 2 Manuela Brandstatter-AUT 2 5)Fallon Sherrock-ENG 4 Maureen Purvis-ENG 3 Maureen Purvis-ENG 0 Nicole Taschner-AUT 0 5)Fallon Sherrock-ENG 0 Shirley Castle-ENG 3 4)Corrine Hammond-AUS 4 Becky King-ENG 0 Shirley Castle-ENG 0 4)Corrine Hammond-AUS 4 Francesca Bevilaqua-ITA 2 Final - Best of 7 legs 4)Corrine Hammond-AUS 3 1)Deta Hedman-ENG 4 2)Aileen De Graaf-NL 3 2)Aileen De Graaf-NL 2 Margaret Sutton-ENG 0 2)Aileen De Graaf-NL 4 Allyson Thomson-ENG 0 Marie Nicholls-ENG 0 Marie Nicholls-ENG 3 2)Aileen De Graaf-NL 4 Julie Newman-ENG 1 7)Danielle Asthon-ENG 2 Roz Heppinstall-ENG 3 Roz Heppinstall-ENG 1 Tina Eggersen-DEN 0 7)Danielle Asthon-ENG 4 7)Danielle Asthon-ENG 3 2)Aileen De Graaf-NL 4 6)Casey Gallagher-ENG 3 6)Casey Gallagher-ENG 1 Morena Wolf-GER 1 6)Casey Gallagher-ENG 4 Cheryl Mcloughin-ENG 2 Silke Goebel-GER 0 Silke Goebel-GER 3 6)Casey Gallagher-ENG 4 Ann-Kathrin Wigmann-GER 3 3)Lisa Asthon-ENG 3 Sieglinde Binder-AUT 0 Ann-Kathrin Wigmann-GER 0 CHAMPION 3)Lisa Asthon-ENG 4 Alina Kourti-GRE 1 Deta Hedman-ENG 3)Lisa Asthon-ENG 3 © Roger Boyesen 2005-2017 http://www.dartsforwindows.com - Darts for Windows v.2.9.2.6 Page 1. -

Kan Onoguchi Marcelo,Bristow

September 2019 Issue 7 | Matt Dennant on Q-School tussle with Duzza Issue 7 Interview JIM WILLIAMS Williams drops by for a chat following his RedDragon Champion of Champions success. Page 36-37 interview KAN ONOGUCHI Darts exists outside Europe. Japanese referee speaks to us about calling the numbers and darts in Japan. Page 21 win Feature winmau vanguard darts MARCELO BRISTOW AND Courtesy of the guys at Winmau, a set , of Vanguard darts will be up for grabs as part of Issue Seven’s competition. TONY O’SHEA Details inside...... We take a look at the life and career of Diogo Portela, Page 40 from his move across to world to his youth as a footballer. Page 14-17 FROM THE YOUTH THE AMATEUR GAME We preview the JDC World Championship, which will be held in Jim Williams lifted the prestigious Champion of Champions, Gibraltar, as well as taking a look at Leighton Bennett’s meteoric while Around the Country provides the latest and Glen rise and Japan’s Sakuto Sueshige. Durrant discusses his time as Teeside darts organiser. Page 26-29 Page 30-33 Challenge tour Photo Credit: Chris Dean, PDC CHALLENGE TOUR RACE HOTS UP AS MENZIES TAKES OVERALL LEAD This weekend saw the penultimate weekend of and Mark Frost Challenge Tour action in 2019 at Aldersley Leisure all reaching the Village in Wolverhampton, and it was not short of last 16. drama with seven different finalists across the four From there, events and now just £1,500 separating the top 6 in those names the Order of Merit. -

Mahtavat Maailman Ykköset Aliisa Ja Tuomas Tie Tähtiin: Mestaruus Vai Tasoitus?

Mahtavat maailman ykköset Aliisa ja Tuomas Tie tähtiin: mestaruus vai tasoitus? Ensin alkuun onnittelut maailmanmestareille Aliisalle ja Tuo- makselle. Teitä hehkutetaan tuolla sisäsivuilla. Onnittelut kuulu- vat myös Tarjalle ja Kirsille. Jäätte valitettavasti junnujen varjoon MM-pronssinne kanssa. 2. kierroksella pudonneet omaan koriinsa rikki komeasti, mutta lisenssipelaajien koh- ja kisa käyntiin, 3. ja 4. kierros vielä omaan dalla olemme alapuolella. 40 seuraa löytyy Risto Spora koriin ja kaksi parasta sieltä jatkoon. Lop- eli siinä ei ole mitään ongelmaa. puosa pelataan semifinaalivaiheeseen asti. Ongelma syntyy kun aletaan tulkita Siinä vaiheessa tulevat taas nämä keräily- liikuntaa. Jos lakia aletaan tulkita samaan eristä mukaan tulleet taas areenalle. Rank- tapaan kuin lakeja Suomessa tulkitaan eli kauksen mukaan sijoitetaan peliparit ja kisa pilkkua viilaten, niin olemme taas tähtäi- Kisojen tulevaisuus jatkuu loppuun asti. messä. On silloin moni muukin laji samas- Ikäkausi- ja sekamestaruuksien jälkeen oli Tässä on eri variaatioita käytettävissä sa veneessä. minulla vahva tunne, että nämä kisat voi- vaikka kuinka. On jopa mahdollista pela- Kun muutama vuosi sitten Veikkauksen si unohtaa. Mutta hetken mietittyäni tulin ta parittomina lohkoina alkuosa ja lopussa monopoli oli vaarassa kaatua tai ainakin sen hieman toisiin aatoksiin ja mieluusti kehit- pelata tikapuufinaalit. asemaa uhattiin, niin meitäkin pyydettiin täisin kisaa lopettamisen sijasta. Sama on- seisomaan Veikkauksen takana eikä lipsu- gelma on osin myös Finnish Openilla. -

Darts for Windows 2.8.9.7 Page 1 - Saturday 03.10.2015 Winmau World Masters Ladies - Singles 08/10/2015 03/10/2015 14:17:48

Winmau World Masters Ladies - Singles 08/10/2015 03/10/2015 14:17:48 Last 256 - Best of 7 legs 1 Deta Hedman-ENG GROUP 1 - Last 128 - Best of 7 legs bye 129 15:50 Deta Hedman-ENG Board 2 Tina Osborne-NZL Tina Osborne-NZL 1 - Last 64 - Best of 7 legs bye 193 17:30 Board 3 1 - Lenka Liptakova-CZE bye 130 15:50 Lenka Liptakova-CZE Board 4 Julie Hunter-NIR Julie Hunter-NIR 2 - Last 32 - Best of 7 legs bye 225 18:20 Board 5 1 - Sarah Roberts (Clwyd)-WAL bye 131 16:15 Sarah Roberts (Clwyd)-WAL Board 6 1 Patricia de Penter-BEL - Patricia de Penter-BEL bye 194 17:30 Board 7 2 - Aleksandra Grzesik-POL bye 132 16:15 Aleksandra Grzesik-POL Board 8 Margaret Kelly-IOM Margaret Kelly-IOM 2 - Last 16 - Best of 7 legs bye 241 18:45 Board 9 - Kate Smith-SCO 1 bye 133 16:40 Kate Smith-SCO Board 10 1 Anna Madigan-NIR - Anna Madigan-NIR bye 195 17:55 Board 11 - Ivy Wieshlow-CAN 1 bye 134 16:40 Ivy Wieshlow-CAN Board 12 2 Aranzazu Hibernon Medina-ESP - Aranzazu Hibernon Medina-ESP bye 226 18:20 13 Board - Sarah Roberts-ENG 2 bye 135 17:05 Sarah Roberts-ENG Board 14 1 15:00 Jolanta Rzepka-POL Board 1 Janni Larsen-DEN 196 17:55 15 Board 15:00 Julie Gore-WAL 2 Board 2 Amy Eden-ENG 136 17:05 Board GROUP 1 WINNER 16 2 15:25 Tove Verket-NOR Board 1 Carina Ekberg-SWE © Roger Boyesen 2005-2015 Darts for Windows 2.8.9.7 http://www.dartsforwindows.com Page 1 - Saturday 03.10.2015 Winmau World Masters Ladies - Singles 08/10/2015 03/10/2015 14:17:48 Last 256 - Best of 7 legs 17 Rachel Brooks-ENG GROUP 2 - Last 128 - Best of 7 legs bye 137 15:50 Rachel Brooks-ENG Board -

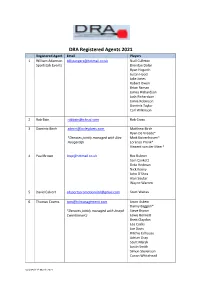

DRA Registered Agents 2021

DRA Registered Agents 2021 Registered Agent Email Players 1 William Adamson [email protected] Niall Culleton Sportstalk Events Brendan Dolan Ryan Hogarth Justin Hood Jake Jones Robert Owen Brian Raman James Richardson Josh Richardson Jamie Robinson Dominic Taylor Carl Wilkinson 2 Rab Bain [email protected] Rob Cross 3 Dominic Birch [email protected] Matthew Birch Ryan De Vreede* *Denotes jointly managed with Alex Maik Kuivenhoven* Hoogerdijk Lorenzo Pronk* Vincent van der Meer* 4 Paul Brown [email protected] Roz Bulmer Sam Cankett Deta Hedman Nick Kenny John O'Shea Alan Soutar Wayne Warren 5 David Calvert [email protected] Scott Waites 6 Thomas Cosens [email protected] Jason Askew Danny Baggish* *Denotes jointly managed with Joseph Steve Brown Cwiertniewicz Lewis Bennett Brett Claydon Lee Cocks Joe Davis Ritchie Edhouse Adrian Gray Scott Marsh Justin Smith Simon Stevenson Conan Whitehead Updated 11th March 2021 7 Joseph [email protected] Danny Baggish* Cwiertniewicz *Denotes jointly managed with Tom Cosens 8 Ian Dargan [email protected] Gordon Mathers 9 Mark Dean [email protected] Devon Petersen* Won-180 *Also manged by James Lincoln 10 Bernardus de Kok [email protected] Jeffrey de Zwaan Lucilex Raymond van Barneveld Management 11 James Duffy [email protected]. Scott Taylor* uk Joe Murnan* *Denotes jointly managed with Daniel Rose 12 Linda Duffy Epic [email protected] Josh Payne Sports Management 13 Mark Elkin [email protected] Kyle Anderson The Sportsman -

Swedish Open 2019 - Ladies Singles 2019-08-18 08:14:03

Swedish Open 2019 - Ladies Singles 2019-08-18 08:14:03 Last 128 - Best of 7 legs 501 GROUP 1 1 1)Lisa Ashton bye - Last 64 - Best of 7 legs 501 65 14:00 1)Lisa Ashton 4 BOARD Kasumi Sato 1 0 2 12:00 Jane Brandt 0 BOARD Kasumi Sato 1 4 Last 32 - Best of 7 legs 501 97 15:00 1)Lisa Ashton 4 Priscilla Steenbergen 0 3 Roz Bulmer bye - 66 12:30 Roz Bulmer 0 BOARD Priscilla Steenbergen 1 4 4 Priscilla Steenbergen bye - Last 16 - Best of 7 legs 501 113 16:00 1)Lisa Ashton Susianne Hägvall 5 Sandra Rasmussen bye - 67 13:00 Sandra Rasmussen 4 BOARD Helena Bruna 1 0 6 Helena Bruna bye - 98 15:30 Sandra Rasmussen Susianne Hägvall 7 Sandra Page bye - 68 13:30 Sandra Page 3 BOARD Susianne Hägvall 1 4 GROUP WINNER 8 Susianne Hägvall bye - © Roger Boyesen 2005-2019 http://www.dartsforwindows.com - Darts for Windows v.2.9.3.1 Page 1 Swedish Open 2019 - Ladies Singles 2019-08-18 08:14:03 Last 128 - Best of 7 legs 501 GROUP 2 9 Andreea Brad bye - Last 64 - Best of 7 legs 501 69 12:00 Andreea Brad BOARD Malin Karlström 2 10 Malin Karlström bye - Last 32 - Best of 7 legs 501 99 15:00 Andreea Brad 4 Helene Sundelin 2 11 Petra Göbel bye - 70 12:30 Petra Göbel 0 BOARD Helene Sundelin 2 4 12 Helene Sundelin bye - Last 16 - Best of 7 legs 501 114 16:00 Andreea Brad 2 8)Maria O´brien 4 13 Kirsty Chubb bye - 71 13:00 Kirsty Chubb BOARD Marita Edenström 2 14 Marita Edenström bye - 100 15:30 Marita Edenström 0 8)Maria O´brien 4 15 Lena Olsson bye - 72 13:30 Lena Olsson BOARD 8)Maria O´brien 2 GROUP WINNER 16 8)Maria O´brien bye Maria O´brien - © Roger Boyesen 2005-2019 -

Williams Scotsman Logo Vector Download Williams Scotsman Logo Vector Download

williams scotsman logo vector download Williams scotsman logo vector download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67b12391ef5d84e0 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. DART PLAYERS NICKNAMES. It seems if you are a dart player you are given a nickname even if this is just a shortened version of your name for example Raymond van Barneveld’s nickname is ‘Barney’ or extended to 'Barney Rubble' from the Flintstones. Raymond sometimes wears a gold Barney Rubble medallion around his neck for good luck! Some nicknames are also based on a professional trade, such as ‘Sparky’, a name given to an electrician and also a nickname used by Wesley Harms and Ricco Vonck. While others can have more of a meaning based upon events such as ‘Jackpot’ used by the two time World Darts Champions, Adrian Lewis. So how did he get his nickname? While competing in the Las Vegas Desert Classic in 2005, Adrian had a go on the slot machines. -

2011 WDF World Rankings: Details Women

WDF World Rankings: Details Women 2011 Nr Player Country Points 1 Deta Hedman England 1926 Dutch Open 2010 150 Points Mariflex Open 2010 120 Points England Classic 2010 120 Points BDO British Classic 2010 120 Points Antwerp Open 2010 120 Points England Masters 2010 120 Points Lakeside World Pro 2011 100 Points BDO British Open 2010 100 Points Zuiderduin Masters 2010 100 Points Finnish Open 2010 90 Points Sweden Open 2010 90 Points Vantaa Sunday Singles 2010 90 Points BDO British Int. Open 2010 80 Points Isle of Man Open 2010 80 Points CenterParcs Masters 2010 80 Points Swiss Open 2010 60 Points Flanders Open 2010 60 Points Czech Open 2010 60 Points England Open 2010 60 Points German Open 2010 48 Points Belgium Open Singles 2010 36 Points Winmau World Masters 2010 30 Points Scottish Open 2010 12 Points 2 Trina Gulliver England 1108 Zuiderduin Masters 2010 180 Points Lakeside World Pro 2011 180 Points BDO British Open 2010 150 Points England Open 2010 120 Points WDF Europe Cup 2010 100 Points Dutch Open 2010 100 Points England Masters 2010 80 Points Isle of Man Open 2010 60 Points BDO British Classic 2010 36 Points England Classic 2010 36 Points BDO British Int. Open 2010 36 Points Winmau World Masters 2010 30 Points Page 1 of 52 WDF World Rankings: Details Women 2011 Nr Player Country Points 3 Irina Armstrong Russia 1102 German Open 2010 100 Points Lakeside World Pro 2011 100 Points Swiss Open 2010 90 Points French Open 2010 90 Points BDO British Open 2010 80 Points Mariflex Open 2010 80 Points Sweden Open 2010 60 Points Belgium Open Singles 2010 60 Points Antwerp Open 2010 60 Points Czech Open 2010 60 Points CenterParcs Masters 2010 60 Points Dutch Open 2010 48 Points Scottish Open 2010 40 Points German Gold Cup 2010 36 Points BDO British Int. -

Helvetia Open 2019 - MS-MENS Singles 09.06.2019 13.06.2019 01:07:37

Helvetia Open 2019 - MS-MENS Singles 09.06.2019 13.06.2019 01:07:37 1 SOUTAR Alan Scotland 2 JUNGHANS Thomas Switzerland 3-4 CALLANDER Euan Scotland VAN_DE_WAL Jitse Netherlands 5-8 TRICOLE Thibault France CARRAGHER Francis Ireland OLDE_KALTER Dennie Netherlands VENMAN Craig England 9-16 WARREN Wayne Wales VAN_EGDOM Jeffrey Belgium SCOTT John England KENNY Nick Wales RASCHINI Francesco Italy EVANS Dave England STAINTON Simon England PETRI Daniele Italy 17-32 MARTI-SANTAMARIA Martin Catalunya REY Patrick Switzerland SPILLER Nicola Switzerland VAN_MANEN Erik Netherlands SCHOEN Fabian Switzerland HAZEL Ben England FRAUENDIENST Rupert Germany CAMACHO Luis Switzerland LOKKEN Brian Denmark LOEFFEL Roman Switzerland LOPEZ Juan Manuel Switzerland TURNER Aaron England WELLINGER Roman Switzerland BELLMONT Stefan Switzerland RAMAN Brian Belgium UNTERBUCHNER Michael Germany 33-64 NIELSEN Bendt O. Denmark SCHAER Marco Switzerland LEUPI Marcel Switzerland GUT Sven Switzerland LUETOLF Jean-Marc Switzerland FUCHS Michael Switzerland SCHMID Michel Switzerland MOOIJMAN Roemer Netherlands HEINZLE Andre Austria BARBEN Marcel Switzerland CASTROVINCI Maurizio Switzerland BIENERT Andreas Germany ALEXANDER Simon England WILSON David England HAENSCH Roman Germany DUBLER Christian Switzerland HAASE Sandro Switzerland WAGNER Nico Germany CRUMP Leon Germany STOEPPLER Dieter Germany EGILSSON Hallgrimur Iceland ARSLAN Slobodan Germany STERCHI Juerg Switzerland BURRI Sven Switzerland SCHELBERT Michael Switzerland STEINACHER Marcel Austria RAMDAJAL Anoop Netherlands