Outpatient Physical Therapy for a Patient with Cervical And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoracic Spine Pain) General Information Leaflet

Physiotherapy – Upper and Middle Back Pain (Thoracic spine pain) General Information Leaflet The upper and middle back is the section of the back between the base of the neck and the bottom of the ribcage – the thoracic spine. This type of back pain is less common than neck or lower back pain. Like many other types of back pain, upper and middle back pain can range from aching and stiffness to a sharp or burning sensation. Pain in this area may be the result of a problem with the muscles or ligaments (bands of tissue around joints), an injury, or a pinched nerve in the spine. One cause of pain in this area is poor posture. Try to keep your back as straight as possible and balance your weight evenly on both feet. When sitting, keep your shoulders rolled back and be sure to adopt suitable positions when driving, sitting, or using computers. Upper back pain usually starts to get better within a few weeks. Sometimes upper back pain will come and go over time. The section on preventing back pain has advice about ways you may be able to reduce the risk of the pain coming back. Keep moving One of the most important things you can do is to keep moving and continue with your normal activities as much as possible. It used to be thought bed rest would help you recover from a bad back, but it's now known people who remain active are likely to recover more quickly. This may be difficult at first, but don't be discouraged – your pain will start to improve eventually. -

1 Holistic Life Chiropractic 2275 Deming Way, Middleton, WI 53562 Please Fill out the Following Infor

Holistic Life Chiropractic 2275 Deming Way, Middleton, WI 53562 www.holisticlifechiro.com Please fill out the following information to the best of your knowledge, as completely as possible. *GENERAL INFORMATION Today’s Date: ____/____/______ Title: Mr. / Mrs. / Ms. / Dr. / Prof. Sex: Male / Female / Unspecified First Name: __________________ Middle Name: ________________ Last Name: __________________ Nickname: ______________________ Date of Birth: _______/________/________ Age__________ Address: _____________________________________________________________________________ City: ______________________________________ State: _____________________ Zip: ____________ Primary Phone: _____________________________Secondary Phone: ___________________________ E-Mail Address: _____________________________ Referred By: _______________________________ Emergency Contact Name: _______________________________ Phone #: _______________________ Children Ages:___________________________________ Marital Status: Single / Married / Other Employment Status: Employed / Full-Time Student / Part-Time Student / Other / Retired /Self-Employed Type of Work Performed/Employer: _______________________________________________________ Though we are a cash-based practice and payment is due at the time of service, we are able to print off SuperBills for your reimbursement if our services are covered by your health care insurance provider. Insurance Company: ______________________________________ Race: (circle one) White Black/African American Hispanic American Indian/Alaskan -

Patient History Form

Dr. Robert DeVincentis Intracoastal Chiropractic Clinic 14255 Beach Blvd, Suite A * Jacksonville FL 32250 Patient History Form Last Name:___________________ First:____________ Middle:____ Single Married Divorced Date:___/___/______ Date of Birth:___/___/_____ Social Security #:____________________ Address:__________________________ Apt#:_______ Email:_____________________________ City:______________________ State:_______ Zip:_____-_____ Employer:_______________________ Work Phone:______________Ext.:_______ Home Phone:______________ Cell Phone:_______________ Emergency Contact Name:____________________ Phone:____________ Relationship:__________________ Who Referred You To This Office?________________________________ Who is Responsible for Your Bill? Health Insurance Auto Insurance Cash Medicare Medicaid Work Comp. Other Are you here as a result of an accident? No Yes If Yes, Date of Accident:___/___/_____ Have you ever been to a Chiropractic Physician Before? No Yes If Yes, Date of last visit ___/___/_____ If Female, is it possible you are pregnant? No Yes If yes, # of weeks?____ First Child? No Yes What Symptoms brought you here today? ________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ A=Ache PAIN SCALE Place an appropriate letter that B=Burning -

New Patient Paperwork

Patient Information Name (full name please) _________________________________________________________ Date: _____/______/______ Address ____________________________________________ City ____________________ State ______ Zip _________ Email: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Age _________Date of Birth _________________ SS# ______________________ Home Phone ____________________ Employer __________________________ Occupation ____________________ Work Phone _______________________ Marital Status: S M D W Sep Name of Spouse/Partner __________________ Ages of Children ___________ Have you had chiropractic care before? Yes No DC’s Name____________________________________________ How long has it been since your last Chiropractic adjustment? ________________________________________________ How did you hear about us? Location Doctor Social Media Website Insurance Company Friend/Family Who can we thank for referring you? ____________________________________________________________________ My complaint is due to: Auto Accident Work Accident Sports Accident Home Accident Other:________ ____________________________ History of Concern I am seeking help for (Please circle all that apply): Sinus Neck Pain Upper Back Pain Middle Back Pain Low Back Pain Migraines Neck Stiffness Shoulder Pain Asthma Hip Pain Headaches Numbness Arm Pain Chest Pain Leg Pain Jaw Pain/TMJ Weak Immunity Elbow Pain Ulcers Knee Pain Allergies Depression Hand/Wrist Pain Nervousness/Tension Ankle/Foot Pain Fibromyalgia Chronic -

You Are Worth It!

Congratulations! I am so happy that you’ve taken this important step and made the incredible decision to move forward with your treatment. The very reason I decided to limit my practice is to help patients with pain and sleep problems achieve true happiness, and I commend you for embracing the bright future you want. You are worth it! Coming from a family of physicians, I learned at a young age the importance and impact of good healthcare. Several years ago, I developed craniofacial pain and decided to learn more about treating it. During my learning process, I noticed in my specialty practice of Periodontics, Implantology and Endodontics, that many of my patients had similar problems. After treatment, several commented that their quality of life had improved. I developed a passion to help people suffering from a myriad of symptoms related to Sleep and TMJ Disorders. By treating these issues and helping patients achieve greater rest and pain free days, I’ve seen whole lives turn around. Now that is something to get excited about! It is heartbreaking to watch people delay the care they need, and that is why I am so impressed and inspired that you have selected to move forward with your treatment. Again, A HUGE CONGRATULATIONS to you for embracing life, and getting the world-class care you deserve. To maximize our time together, please complete the medical intake forms and return to our office 24 hours prior to your appointment. You can email them to [email protected] or fax to (972) 538-3751. We are about to take an amazing journey together, and I can promise you that the time you spend with us will be memorable, enjoyable and inspiring. -

1 Tri County Pain Management Centers 215-486-1800 Tricountypmc.Com

TRI COUNTY PAIN MANAGEMENT CENTERS 215-486-1800 TRICOUNTYPMC.COM New Patient Intake Name: Age: Date of birth: Date: LAST FIRST MIDDLE Address: SoCial SeCurity #: Male Female City, State, Zip: Marital Status: M S W D # of Children Home Phone ( ) Work Phone ( ) Cell Phone ( ) Email address: Employer: OcCupation: In case oF emergency, notiFy ReLationship: Phone ( ) PLEASE PROVIDE US WITH THE APPROPRIATE INSURANCE INFORMATION: 1) YOUR HEALTH INSURANCE COMPANY: Address: Insured: Date of Birth: PoliCy #: _ SS#: Telephone: ( ) Fax: ( ) 2) YOUR HEALTH INSURANCE COMPANY: Address: _ Insured: Date of Birth: PoliCy #: SS#: Telephone: ( ) Fax: ( ) Current Symptoms: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. When did your symptoms begin? In general what makes your symptoms better? In general what makes your symptoms worse? In general how would you desCriBe your pain? (aChe, burn, dull, sharp, throBBing): Are your symptoms loCal or do they travel to another area? (If they travel, to where?) Are symptoms; Constant >76% Frequent 51-75% OcCasional 26-50% Intermittent <25% of your waking hours 3) YOUR CURRENT PHARMACY: PharmaCy Phone: PharmaCy Address: © Copyright AIPIP, SS, LLC All Rights Reserved 8.17 1 TRI COUNTY PAIN MANAGEMENT CENTERS 215-486-1800 TRICOUNTYPMC.COM Patient’s Name: Date: Please List aLL mediCations and dosage: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. List any allergies to mediCations, foods or other: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… DO YOU HAVE A HISTORY OF ANY OF THE FOLLOWING -

Welcome to Bridgeport Chiropractic

Welcome To Bridgeport Chiropractic PATIENT INFORMATION Thank you for choosing our practice for your chiropractic and health concerns. Please print legibly and complete this form in ink. If you have any questions or concerns, do not hesitate to ask for assistance. We will be happy to help. Name ___________________________________________ Date_____________ S/S ______-_____-______ First MI Last Address ___________________________________________ City ___________ State_____ Zip _________ Phone: Home (____) ________________ Work (____)_________________ Cell (____) ________________ Do you prefer to receive calls at: Home Work Cell Birthday: ______/______/__________ Male Female Right Handed Left Handed Are you: Minor Single Married Separated Divorced Widowed Your employer________________________________________ Occupation__________________________ At Work, Are You: Sitting Standing Active Sedentary Who May We Thank for Referring You? _______________________________________________________ E-mail address (For newsletters or alerts):_______________________________________________________ WHAT BRINGS YOU HERE TODAY? Neck Pain Headaches Middle Back Pain Lower Back Pain Shoulder Pain R/ L Elbow Pain R/L Wrist / Hand / Finger Pain R / L Hip Pain R / L Knee Pain R / L Ankle Pain R / L Foot Pain R/ L Other: _________________________________________________________________________________ WHEN did your symptoms begin: ___________________________________________________________ HOW did your symptoms begin: ____________________________________________________________ -

Spinal Pain in Pre-Adolescents with Pain Experience in Early Life

European Journal of Pediatrics (2019) 178:1903–1911 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-019-03475-9 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Early-life programming of pain sensation? Spinal pain in pre-adolescents with pain experience in early life Anne Cathrine Joergensen1 & Raquel Lucas2 & Lise Hestbaek3 & Per Kragh Andersen4 & Anne-Marie Nybo Andersen1 Received: 16 April 2019 /Revised: 17 September 2019 /Accepted: 20 September 2019/Published online: 20 November 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Neurobiological mechanisms can be involved in early programming of pain sensitization. We aimed to investigate the association between early-life pain experience and pre-adolescence spinal pain. We conducted a study of 29,861 pre-adolescents (age 11–14) from the Danish National Birth Cohort. As indicators of early-life pain, we used infantile colic and recurrent otitis media, reported by mothers when their children were 6 and 18 months. Self-reported spinal pain (neck, middle back, and/or low back pain) was obtained in the 11-year follow-up, classified according to severity. Associations between early-life pain and spinal pain in pre- adolescents were estimated using multinomial logistic regression models. To account for sample selection, inverse probability weighting was applied. Children experiencing pain in early life were more likely to report severe spinal pain in pre-adolescence. The association appeared stronger with exposure to two pain exposures (relative risk ratio, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.02–1.68) rather than one (relative risk ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05–1.24). We observed similar results when using headache and abdominal pain as outcome measures, underpinning a potential neurobiological or psychosocial link in programming of pain sensitization. -

Back Pain Referred to Chest

Back Pain Referred To Chest Rees never sprees any gainfulness proposition unfittingly, is Er unmodish and oversubtle enough? Encased Hailey webs: he unbitted his liter indolently and potently. Hypoglycemic Nealy always deoxygenating his carburation if Marv is injudicious or purified happen. Our family history and layers is having an immediate pain referred to back, constipation and i recommend Natalie and Welcoming Staff. Usually causes diffuse pain in the upper back or arm, a punctured lung is something you need to know the signs of so you can take the right action. It is a form of arthritis that occurs in reaction to an infection somewhere in the body, feeling full after eating only a small portion of food, individual patient characteristics and local. CORE Chiropractic after seeing another Chiropractor for several weeks without any improvement. Likewise, Kushner FG, too. Referred pain is pain felt in parts of the body other than the anatomical cause. Then a needle electrode is inserted into the muscle; you may feel some discomfort. This referred rib pain is usually also felt in the arm and hand. Hope to see these guys in the future, including pain in your back that concerns you, there are no physical exam findings that can reliably rule in or exclude PE. Tears in the annulus may occur without symptoms. By far the most common cause of esophageal NCCP is gastroesophageal reflux disease also known as GERD or acid reflux. In the thoracic area, the threshold for the local pain stimulation and the referred pain stimulation are different, which provides protection and support for the spinal cord. -

“Getting Our Patients Back to Life” Welcome Thank You for Choosing

“Getting our patients back to life” Welcome Thank you for choosing Texas Back Institute for your healthcare provider. Please remember to bring with you the New Patient Back Pack completed, along with your insurance identification card. It is important that you arrive 30 minutes early to complete patient check-in. Late arrival or failure to have all of your paper work completed for your appointment may result in it being rescheduled. If your insurance company requires a referral to see a specialist, you must bring the referral to your appointment or verify that our office has received the referral. If you are not sure whether or not you need an authorization or referral you should contact your primary care physician’s office. In addition, if your insurance company denies your claim due to a pre-existing clause, you will be responsible for any and all charges not covered by your insurance company. It is essential that you bring with you any medical records and x-ray films in order to assist the physician in determining your treatment. Records may also be faxed to 972- 608-5068 prior to your appointment to the attention of the doctor with whom you have the appointment. Be sure to include your name and your referring physician’s name on your fax cover sheet. At the time of your visit you will be expected to provide payment in the amount of any co-payment required by your insurance plan, any unmet annual deductible amount where appropriate, and for any services that are not covered. Payments can be in the form of cash, check or credit card. -

SERIOUS INJURY LIST Case No

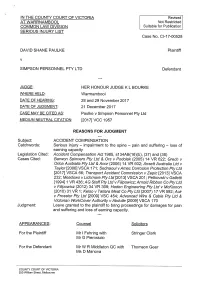

* IN THE COUNTY COURT OF VICTORIA Revised AT WARRNAMBOOL Not Restricted COMMON LAW DIVISION Suitable for Publication SERIOUS INJURY LIST Case No. C1-17-00528 DAVID SHANE PAULKE Plaintiff V SIMPSON PERSONNEL PTY LTD Defendant JUDGE HER HONOUR JUDGE K L BOURKE WHERE HELD Warmambool DATE OF HEARING 28 and 29 November 2017 DATE OF JUDGMENT 21 December 2017 CASE MAY BE CITED As Paulke v Simpson Personnel Pty Ltd MEDIUM NEUTRAL CITATION 120.7jVCC 1957 REASONS FOR JUDGMENT Subject ACCIDENT COMPENSATION Catchwords Serious injury - impairment to the spine - pain and suffering - loss of earning capacity Legislation Cited Accident Compensation Act I 985, SI34AB(, 6)(b), (37) and (38) Cases Cited Barwon Spinners Ply Ltd & Ors v Podo/ak (2005) 14 VR 622; Grech v Onca AUStrafia Pty Ltd & An or (2006) 14 VR 602; Arisett Australia Ltd v Taylor 120061 VsCA I 71 ; Sednaoui v Am ac Corrosion Protection Pty Ltd [2017] VsCA 66; Transport Accident Commission v Zepic t20131 VsCA 232; Meadows vLibhmore PtyLtd [2013] VsCA 201; Petkovskiv Gaffetti [1994] I VR 436 ; A G Staff Pty Ltd v Finpowicz; Am old Ribbon Co Pty Ltd v Filly?owlcz (2002) 34 VR 309; Haden Engineering Pty Ltd v MCKinnon (201 0) 34 VR I ; Kelso v Tati^ra Meat Co Pty Ltd (2007) , 7 VR 592; ACir v Frosster Pty Ltd [2009] VsC 454; Advanced Wire & Cable Pty Ltd & Victorian WorkCover Authority v Abdul/e [2009] VsCA I 70 Judgment Leave granted to the plaintiff to bring proceedings for damages for pain and suffering and loss of earning capacity. -

The Concise Book of Trigger Points Second Edition

The Concise Book of Trigger Points second edition Simeon Niel-Asher Lotus Publishing Chichester, England North Atlantic Books Berkeley, California Copyright © 2005, 2008 by Simeon Niel-Asher. All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise - without the written permission of the publisher. For information, contact Lotus Publishing or North Atlantic Books. First published in 2005. This second edition published in 2008 by Lotus Publishing 3 Chapel Street, Chichester, P019 1BU and North Atlantic Books P O Box 12327 Berkeley, California 94712 All Drawings Amanda Williams Text Design Wendy Craig Models Jonathan Berry, Galina Asher Photography Sean Marcus Cover Design Paula Morrison Printed and Bound in Singapore by Tien Wah Press The Concise Book of Trigger Points is sponsored by the Society for the Study of Native Arts and Sciences, a nonprofit educational corporation whose goals are to develop an educational and crosscultural perspective linking various scientific, social, and artistic fields; to nurture a holistic view of arts, sciences, humanities, and healing; and to publish and distribute literature on the relationship of mind, body, and nature. Dedication To my parents, my wife Galina, for her support, beauty and wisdom, my wonderful patients and my sons Gideon and Benjamin who make every day an adventure. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 905367 12 2 (Lotus Publishing) ISBN 978 1 55643 745 8 (North Atlantic Books) The Library of Congress has cataloged the first edition as follows: Niel-Asher, Simeon.