The Mousetrap, & Other Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mousetrap the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Mousetrap The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Mark Light-Orr in The Mousetrap, 2002. The ContentsMousetrap Information on the Play Background Information 4 Synopsis 6 Characters 7 About the Playwright 8 Scholarly Articles on the Play Activities 9 Examining The Mousetrap 11 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Background Information By Christine Frezza From Insights, 2007 By 1947, Agatha Christie was a much-published writer of mysteries and an occasional play- wright, with two productions to her credit. Ira Levin, in his introduction to The Mousetrap and Other Plays, said that Christie felt other playwrights who adapted her novels made the mistake of “following the books too closely” (Agatha Christie, 1978, p. -

Chapter One Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background of The Study Agatha Christie is a British author in the 20th century who is famous for her novels. She is also famous for her plays, such as The Mousetrap, and short stories, such as The Submarine Plans and The Second Gong. She is considered to be one of the most famous murder mystery writers. She is clever at making stories and unforgettable detective characters. Agatha Christie has made a great contribution to the world of literature, especially in the genre of detective story. Most of her works have been filmed and the stories of her two famous detective characters, Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot, have been made into a serial in television and radio versions. Miss Marple looks like an ordinary old woman. She does not like a detective at all, yet with her ability to observe human nature, she can solve a murder case with her shrewd observation. Hercule Poirot is a Belgian man who has interesting physical appearance and also eccentric manners. His first appearance is in Christie’s first book, Mysterious Affair at Styles. It is difficult for someone to argue with him for he has strong character. His famous tool in identifying murder case is called “grey cells.” He always finishes each case with a dramatic denouement. 1 Maranatha Christian University In this thesis, I would like to analyse one of the many world famous Christie’s books, Towards Zero. This novel, which is a whodunit story, was written in 1944. Whodunit story is “a novel or drama concerning a crime (usually a murder) in which a detective follows clues to determine the perpetrator” (“who- dun-it”). -

The Mousetrap

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Taylor Theatre Playbills Campus Events 10-20-1976 The ouM setrap Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/playbills Part of the Acting Commons, Dance Commons, Higher Education Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation "The ousM etrap" (1976). Taylor Theatre Playbills. 261. https://pillars.taylor.edu/playbills/261 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus Events at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Taylor Theatre Playbills by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University Theatre Fl-esents A3ntho Chrisfie's Little Theatre Octob er 70,?1,?2,+?3 ) t176 AGATHA CHRISTIE was born in Torquay, England. Her THE MOUSETRAP early schooling was highly informal; the young Agatha was tutored by her motier who encouraged her imaginative offspring to pursue her natrual talents for Director: Jessie Rousselow piano and voice. Later, at the prodding of a neighbor, Designer: Ollie Hubbard Eden Philpott, the successful novelist, Miss Christie tried her hand at writing and found-her natural and lasting THE CAST niche in life. (in the order of their appearnce) Miss Christie married twice: first to Colonel Archibald Christie of the British Air Corps; and later to Max MollieRalston..... ....KimMontgomery. Mallowan, a noted archeologist. Miss Christie accompanied her husband on his periodic expeditions - Giles Ralston . Jay Cunningham and one such trip gave her the inspiration and background for her mystery novel MURDER lN Christopherwren ... BillWallace MESOPOTAMIA. - Agatha Christie was unquestionably one of the most Mrs.Boyle ...KathyTurner prolific as well as one of the most successful mystery writers of all time. -

Centrespread

14 centrespread centrespread 15 SEPTEMBER 13-19, 2015 SEPTEMBER 13-19, 2015 Meet the Sleuths Unlike Arthur Conan Doyle, who is synonymous with Sherlock Holmes, Christie The Life & Times of created more than one ace detective for her novels, short stories and plays: Dame Agatha Christie September 15, 1890: Born Agatha Mary ers takes them through four novels and Hercule Poirot: A moustache waxed to perfec- Clarissa Miller to an American father and one short story collection and their stories tion that he is inordinately proud of, supreme British mother in Torquay, Devon, now the confidence in his “little grey cells” and a devo- were reportedly the ones Christie enjoyed site of the Agatha Christie festival tion to “order and method” are among the best- writing the most known traits of Monsieur Poirot. A retired December 1914: Following a whirlwind member of the Belgian detective force, Poirot Harley Quinn: This mysterious fig- courtship, Agatha marries Archie Christie, a makes his debut in The Mysterious Affair At ure who seems to appear and disappear qualified aviator Styles and went on to feature in 33 novels and suddenly is supposed to be Christie’s Murder, 54 short stories. When Curtain: Poirot’s Last favourite character. He operates through 1916: Partly because of a bet with her sister, Case was published in 1974, The New York the more worldly Mr Satterthwaite, who he partly to dispel the boredom of her work at a Times gave the detective a front-page obituary, guides in the investigations. Christie dedi- dispensary during World War I, she writes her the only fictional character to get that honour cated the collection of short stories The debut detective novel, she Mysterious Mr Quinn to the character The Mysterious Affair At Miss Marple: A fussy old lady in the village himself Styles of St Mary Mead, Jane Marple is the anti the- sis of Hercule Poirot but is as well known. -

The Mousetrap by Agatha Christie

April 26 – May 22, 2016 on the One America Mainstage STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts with contributions by Janet Allen, Courtney Sale Robert M. Koharchik, Alison Heryer, Michelle Habeck, David Dabbon Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com SEASON SPONSOR 2015-2016 ASSOCIATE LEAD SPONSOR SPONSOR YOUTH AUDIENCE & PRODUCTION PARTNER FAMILY SERIES SPONSOR MATINEE PROGRAMS SPONSOR The Mousetrap by Agatha Christie Welcome to the classic Agatha Christie mystery thriller: a houseful of strangers trapped by a blizzard and stalked by an unknown murderer. The Mousetrap is the world’s longest running stage play, celebrating its 64th year in 2016. Part drawing room comedy and part murder mystery, this timeless chiller is a double-barreled whodunit full of twists and surprises. Student Matinees at 10:00 A.M. on April 28, May 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12 Estimated length: 2 hours, 15 minutes, with one intermission Recommended for grades 7-12 due to mild language Themes & Topics Development of Genre Deceit and Disguise Gender and Conformity Xenophobia or Fear of the Other Logic Puzzles Contents Director’s Note 3 Executive Artistic Director’s Note 4 Designer Notes 6 Author Agatha Christie 8 10 Commandments of Detective Fiction 11 Agatha Christie’s Style 12 Other Detective Fiction 14 Academic Standards Alignment Guide 16 Pre-Show Activities 17 Discussion Questions 18 Activities 19 Writing Prompts 20 Resources 21 Glossary 23 Going to the Theatre 29 Education Sales Randy Pease • 317-916-4842 cover art by Kyle Ragsdale [email protected] Ann Marie Elliott • 317-916-4841 [email protected] Outreach Programs Milicent Wright • 317-916-4843 [email protected] Secrets by Courtney Sale, director What draws us in to the murder mystery? There is something primal yet modern about the circumstances and the settings of Agatha Christie’s stories. -

Agatha Christie

book & film club: Agatha Christie Discussion Questions & Activities Discussion Questions 1 For her first novel,The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Agatha Christie wanted her detective to be “someone who hadn’t been used before.” Thus, the fastidious retired policeman Hercule Poirot was born—a fish-out-of-water, inspired by Belgian refugees she encountered during World War I in the seaside town of Torquay, where she grew up. When a later Poirot mystery, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, was adapted into a stage play, Christie was unhappy that the role of Dr. Sheppard’s spinster sister had been rewritten for a much younger actress. So she created elderly amateur detective Jane Marple to show English village life through the eyes of an “old maid”—an often overlooked and patronized character. How are Miss Marple and Monsieur Poirot different from “classic” crime solvers such as police officials or hard-boiled private eyes? How do their personalities help them to be more effective than the local authorities? Which modern fictional sleuths, in literature, film, and television, seem to be inspired by Christie’s creations? 2 Miss Marple and Poirot crossed paths only once—in a not-so-classic 1965 British film adaptation of The ABC Murders called The Alphabet Murders (played, respectively, by Margaret Rutherford and Tony Randall). In her autobiography, Christie writes that her readers often suggested that she should have her two iconic sleuths meet. “But why should they?” she countered. “I am sure they would not enjoy it at all.” Imagine a new scenario in which the shrewd amateur and the egotistical professional might join forces. -

The Mousetrap

2013 – 2014 SEASON THE MOUSETRAP by Agatha Christie CONTENTS Directed by Paul Mason Barnes 2 The 411 3 A/S/L & RBTL 4 FYI 6 HTH 7 B4U 8 F2F 10 IRL 12 SWDYT MAJOR SPONSOR: WELCOME! At The Rep, we know The desire to learn, insatiable when awakened, can that life moves sometimes lie dormant until touched by the right teacher or fast—okay, really the right experience. We at The Rep are grateful to have the fast. But we also opportunity to play a role supporting you as you awaken the know that some desire for learning in your students. things are worth Who doesn’t like a good puzzle with clues, oddities and slowing down for. We believe that live theatre is plenty of red herrings? Agatha Christie’s classic whodunit one of those pit stops worth making and are excited that you shows your students the danger in making judgments about are going to stop by for a show. To help you get the most bang people based on their looks and behavior as revealed secrets for your buck, we have put together WU? @ THE REP—an make everyone question their assumptions. Your students IM guide that will give you everything you need to know to will use observation and inferential reasoning while having a get at the top of your theatergoing game—fast. You’ll find good time identifying the murderer at Monkswell Manor. character descriptions (A/S/L), a plot summary (FYI), biographical information (F2F), historical context (B4U), It would be a good idea to take a minute on the bus to give and other bits and pieces (HTH). -

Christie History

St Martin’s Theatre in London's West End Running continuously for over 60 years, The Mousetrap has broken records in London’s West End and established Agatha Christie as a playwright in the public eye. Since its debut in 1952, it has become the longest running play in the history of London’s West End with the 25,000th performance taking place on November 18, 2012. The 25,000th performance was marked with a one-oK star studded performance, introduced by Christie's grandson Mathew Prichard and featuring Patrick Stewart, Julie Walters, and Miranda Hart. The performance accompanied the unveiling of the Agatha Christie memorial statue in Leicester SQuare which commemorated her great works and her contributions to the theatre. The story was adapted from a radio play, Three Blind Mice , written for the Royal family in 1947. The stage play had to be renamed on the insistence of another producer, Emile Littler, who had used the name on stage before the Second World War, and it was Agatha Christie’s son-in-law Anthony Hicks who suggested the new title. In fact, it refers to Shakespeare’s Hamlet , in which Hamlet cryptically calls the play depicting the murder of the king "The Mousetrap." The original West End cast included Richard Attenborough and his wife Sheila Sim. One actor has been included in every performance since the opening night and that is Deryck Guyler, whose voice recording reads the radio news bulletin in every show at St Martin’s Theatre. 9 PLAYBILL Agatha Christie gave the rights to The Mousetrap to LeZ: Ty Mayberry and Anne her grandson Mathew Prichard for his 9th birthday, Quackenbush in the Alley “Mathew, of course, was always the most lucky Theatre's The Mousetrap (2003). -

If You Want to Read the Books in Publication

If you want to read the books in publication order before you discuss them this is the list for you. For the books the year indicates the first publication, whether in the US or UK, and where possible we have given the alternative US/UK titles. The collections listed are those that feature the first book appearance of one or more stories: 1920 The Mysterious Affair at Styles 1922 The Secret Adversary 1923 Murder on the Links 1924 The Man in the Brown Suit 1924 Poirot Investigates – containing: The Adventure of the ‘Western Star’ The Tragedy at Marsdon Manor The Adventure of the Cheap Flat The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge The Million Dollar Bond Robbery The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan The Kidnapped Prime Minister The Disappearance of Mr Davenheim The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman The Case of the Missing Will 1925 The Secret of Chimneys 1926 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1927 The Big Four 1928 The Mystery of the Blue Train 1929 The Seven Dials Mystery 1929 Partners in Crime – containing: A Fairy in the Flat A Pot of Tea The Affair of the Pink Pearl The Adventure of the Sinister Stranger Finessing the King/The Gentleman Dressed in Newspaper The Case of the Missing Lady Blindman’s Buff The Man in the Mist The Crackler The Sunningdale Mystery The House of Lurking Death The Unbreakable Alibi The Clergyman’s Daughter/The Red House The Ambassador’s Boots The Man Who Was No.16 1930 The Mysterious Mr Quin – containing: The Coming of Mr Quin www.AgathaChristie.com The Shadow on the Glass At the ‘Bells -

Hercule Poirot

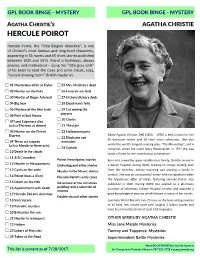

GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY AGATHA CHRISTIE’S AGATHA CHRISTIE HERCULE POIROT Hercule Poirot, the “little Belgian detective”, is one of Christie's most famous and long-lived characters, appearing in 33 novels and 65 short stories published between 1920 and 1975. Poirot is fastidious, always precise, and methodical – using the “little gray cells” of his brain to read the clues and solve classic, cozy, “locked drawing room” British mysteries. 01 Mysterious affair at Styles 25 Mrs. McGinty's dead 02 Murder on the links 26 Funerals are fatal 03 Murder of Roger Ackroyd 27 Hickory dickory dock 04 Big four 28 Dead man's folly 05 Mystery of the blue train 29 Cat among the pigeons 06 Peril at End House 30 Clocks 07 Lord Edgeware dies (a/k/a Thirteen at dinner) 31 Third girl 08 Murder on the Orient 32 Halloween party Express Dame Agatha Christie, DBE (1890 – 1976) is best known for her 33 Elephants can 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections. She also 09 Three act tragedy remember (a/k/a Murder in three acts) wrote the world's longest-running play, “The Mousetrap”, and 6 34 Curtain romances under the name Mary Westmacott. In 1971 she was 10 Death in the clouds made a Dame for her contribution to literature. 11 A B C murders Poirot investigates: stories Born into a wealthy upper-middle-class family, Christie served in 12 Murder in Mesopotamia Underdog and other stories a Devon hospital during WWI, tending to troops coming back 13 Cards on the table Murder in the Mews: stories from the trenches, before marrying and starting a family in London. -

'The Mousetrap' at Metropolis Arts Theatre

THEATER REVIEW: ‘THE MOUSETRAP’ AT METROPOLIS ARTS THEATRE Jeff Nelson February 15, 2019 Here is your next bar bet: Name the longest running play in a major theater market. No, it is not “Phantom of the Opera” on Broadway; it is Agatha Christie’s “The Mousetrap’ in the fashionable theatre district of London’s West End. It opened in the fall of 1952, just before Eisenhower was elected president, and is still running. Yes, 27,000 performances later, “The Mousetrap” remains an icon of theatrical longevity among the slots in the major theatrical markets and a testimonial to the eternal appeal of the criminal world of Agatha Christie. The current production of director Joe Lehman at Arlington Heights’ Metropolis Arts Theatre is a pleasant reminder of why this play will be staged as long as there is an audience for crime thrillers. But first, a word about the play’s author, Dame Agatha Christie. In her 86 years, she created 66 novels that were written in her own name, 6 romance novels under the name of Mary Westmacott, 3 non-fiction memoirs, and she even found time to pen 2 volumes of poetry. At any time, any one of her 30 plays (note—10 were more were discovered in 2015) are being performed displaying the worldwide demand for her stories. That body of writing currently appears around the world in 103 languages. Colin Lawrence, Emma Baker and David Moreland (right). Photo by Ellen Prather. Her sales of 2 billion copies and counting, puts her historically in third place behind only “The Bible” and the works of Shakespeare. -

Hercule Poirot – the Fictional Canon

Hercule Poirot – The fictional canon Rules involving "official" details of the "lives" and "works" of fictional characters vary from one fictional universe to the next according to the canon established by critics and/or enthusiasts. Some fans of Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot have proposed that the novels are set on the date they were published, unless the novel itself gives a different date. It has further been proposed that only works written by her (including short stories, the novels and her play Black Coffee) are to be considered canon by most fans and biographers. This would render everything else (plays, movies, television adaptations, etc.) as an adaptation, or secondary material. A contradiction between the novels can be resolved, in most cases, by going with the novel that was published first. An example of this would be the ongoing controversy over Poirot's age. Taken at face value it appears that Poirot was over 125 years old when he died. Though the majority of the Hercule Poirot novels are set between World War I and World War II, the later novels then set him in the 1960s (which is contemporary with the time Agatha Christie was writing even though it created minor discrepancies). Many people believe, from her later works, that Poirot retired from police work at around 50, but this is untrue, because as shown in the short story "The Chocolate Box", he retired at around 30. By accepting the date given in "The Chocolate Box" over later novels, which never gave precise ages anyway, it can be explained why Poirot is around for so long.