Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Artist: Breaking Into the Pop Industry

® CREATIVELY AND INDEPENDENTLY PRODUCED BY THE RESIDENTS OF LAKE NONA DECEMBER 2020 Volume 5 | Issue 12 The ArArtist:tist: Breaking IntIntoo the Pop IndustrIndustryy PAGE 5 Artist: Luke Gage LET’S TALK LAKE NONA: AUGMENTED REALITY IN THE OR 11 WHY WE NEED A LIBRARY BUSINESS SPOTLIGHT: THINGS ARE LOOKING UP 6 IN LAKE NONA 13 ILINGO ACADEMY 14 Orlando, FL 32827 FL Orlando, 6555 Sanger Rd Sanger 6555 Nonahood News LLC News Nonahood EDITOR'S NOTE ® CREATIVELY AND INDEPENDENTLY PRODUCED BY THE RESIDENTS OF LAKE NONA Editor’s Note: Publishers/Owners 20 Discoveries Made Rhys & Jenny Lynn Through Having Editor-in-Chief 2020-Vision Demi Taveras Director of Content BY DEMI TAVERAS, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nicole LaBosco 1. Always have back-up rolls of toilet paper. Production Manager 2. Thank the healthcare workers. All. The. Time. They’re Kyle Hamm superheroes. by those occasions, I mean the tragic passing of Kobe 3. Keep hand sanitizer on your person always! Why did we and Gianna Bryant, Chadwick Boseman, Ruth Bader Writers & Reporters ever go out without it? Ginsburg, Naya Rivera, Alex Trebek, and many more. You will all be missed very much. Amber Harmon, Andrew Gordon, Ashley Cis- 4. Go outside and take a walk. I promise it’ll help. neros Mejia, Camille Ruiz Mangual, Cindy -Coff 15. We’ve progressed past the need to continue blowing out 5. Zoom happy hours are just work meetings on a Friday man, Daniel Pyser, Demi Taveras, Dennis Dele- candles on a birthday cake. It’s just impossible to forget the afternoon in disguise. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short -

Mcleod Bethune Papers: the Bethune Foundation Collection Part 2: Correspondence Files, 1914–1955

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier BethuneBethuneMaryMary McLeod PAPERS THE BETHUNE FOUNDATION COLLECTION PART 2: CORRESPONDENCE FILES, 19141955 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Mary McLeod Bethune Papers: The Bethune Foundation Collection Part 2: Correspondence Files, 1914–1955 Editorial Adviser Elaine Smith Alabama State University Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide Compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bethune, Mary McLeod, 1875–1955. Mary McLeod Bethune papers [microform] : the Bethune Foundation collection microfilm reels. : 35 mm. — (Black studies research sources) Contents: pt. 1. Writings, diaries, scrapbooks, biographical materials, and files on the National Youth Administration and women’s organizations, 1918–1955. pt. 2. Correspondence Files, 1914–1955. / editorial adviser, Elaine M. Smith: project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. Accompanied by printed guide with title: A guide to the microfilm edition of Mary McLeod Bethune papers. ISBN 1-55655-663-2 1. Bethune, Mary McLeod, 1875–1955—Archives. 2. Afro-American women— Education—Florida—History—Sources. 3. United States. National Youth Administration—History—Sources. 4. National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (U.S.)—History—Sources. 5. National Council of Negro Women— History—Sources. 6. Bethune-Cookman College (Daytona Beach, Fla.)—History— Sources. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

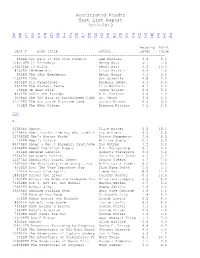

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Accelerated Reader Test List Report 2012-2013 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Reading Point Test # Book Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 922EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5.0 128370EN 11 Birthdays Wendy Mass 4.1 7.0 146272EN 13 Gifts Wendy Mass 4.5 13.0 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Maifair 4.4 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.1 3.0 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 4.8 2.0 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 3.1 2.0 6651EN The 24-Hour Genie Lila McGinnis 4.1 2.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 5.2 5.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.5 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 3.9 1.0 31170EN The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman 4.3 3.0 413EN The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson 4.3 2.0 TOP A 64593EN Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15.0 61248EN Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved B Kay Winters 3.6 0.5 127685EN Abe's Honest Words Doreen Rappaport 4.9 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 6.2 3.0 86479EN Abner & Me: A Baseball Card Adve Dan Gutman 4.2 5.0 54088EN About the B'nai Bagels E.L. Konigsburg 4.7 5.0 815EN Abraham Lincoln Augusta Stevenson 3.2 3.0 29341EN Abraham's Battle Sara Harrell Banks 5.3 2.0 11577EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7.0 12573EN The Absolutely True Story...How Willo Davis Robert 5.1 6.0 6001EN Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.0 3.0 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 8.9 11.0 18801EN Across the Lines Carolyn Reeder 6.3 10.0 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory -

A Glance at Stephen King's Life

Appendix: I A Glance at Stephen King’s Life Illustration 20: Stephen King 182 Stephen Edwin King was born on September 21, 1947 in Portland, Maine, USA, to Donald Edwin King and Nellie Ruth Pillsbury. When he was two years old, his father (born David Spansky) deserted his family and Ruth raised Stephen and his brother David by herself, sometimes under great financial strain. The family moved to Ruth’s home town of Durham, Maine but also spent brief periods in Fort Wayne, Indiana and Stratford, Connecticut. King attended Durham Elementary Grammar School and then nearby Lisbon High School. He has been writing since an early age. When in school, he wrote stories plagiarised from what he’d been reading at the time, and sold them to his friends. This was not popular among his teachers, and he was forced to return his profits when this was discovered. From 1966 to 1970, King studied English at the University of Maine at Orono. There, King wrote a column in the school magazine called “King’s Garbage Truck”. At the university, he also met Tabitha Spruce who he married in 1971. King took on odd jobs to pay for his studies. One of them was at an industrial laundry, from which he drew material for the short story “The Mangler”. This period in his life is readily evident in the second part of Hearts in Atlantis After finishing his university studies with a Bachelor of Science in English and obtaining a certificate to teach high school, King took a job as an English teacher at Hampden Academy in Hampden, Maine. -

Jefrë: the Beacon and Code Wall Artist on Page 16

® CREATIVELY AND INDEPENDENTLY PRODUCED BY THE RESIDENTS OF LAKE NONA NOVEMBER 2018 Volume 3 | Issue 10 Jefrë: The Beacon and Code Wall Artist on page 16 NATURAL KILLER CELLS MAY OPEN NEMOURS CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL WINS NONA CYCLE: FELLOWSHIP, FUN AND SPECIAL EDITION INSERT: LIFESAVING CANCER TREATMENTS TO FLORIDA HOSPITAL ASSOCIATION AWARD FUNDRAISING E14 SANTA'S WORKSHOP IN THIS ISSUE MORE PATIENTS 4 FOR INNOVATION IN PATIENT CARE 19 LOCAL LEADERS, 4 BUSINESS & REAL ESTATE, 6 FEATURES, 16 HEALTH & WELLNESS, 22 EDUCATION, 26 EVENTS & ACTIVITIES, E2 FOOD & DRINKS E4 LIFESTYLE E5 SPORTS & FITNESS E13 ARTS & CULTURE E17 NONAHOOD CALENDAR, E23 Orlando, FL 32827 FL Orlando, 6555 Sanger Rd Sanger 6555 Nonahood News LLC News Nonahood ® EDITOR'S NOTE CREATIVELY AND INDEPENDENTLY PRODUCED BY THE RESIDENTS OF LAKE NONA While last month it seemed that the ology ... but we also have Briel Royce, a Awestruck, common thread was change – prepar- nine-year-old who just earned herself a Publishers ing for it, accepting it, embracing it, cre- spot at the sixth annual Drive, Chip and Rhys & Jenny Lynn ating it, coping with it – this month’s ed- Putt National Finals at Augusta Nation- But Not at itorials are quite empowering and teach al Golf Club … and Katie Graumann who Lead Web Developer us ways to be present in the moment won six gold and two silver medals with Michael Perez A Loss for and be our best selves through positive- her team at this year’s European Cham- Editor-in-Chief thinking, good health, building rela- pionship for Dragon Boating! Elaine Vail Words tionships, and serving others. -

Probate Index

Probate Index Name Probate Number Date Filed Attorney Austin, Annie J,Minor 872 02/06/33 Chas V Yeamans Adkins, M R 952 08/13/35 R F Peden, Jr Aushutz, Viola I R & 1009 12/01/36 George E B Peddy Golda June, Gdn'shp Anderson, W M 1066 06/22/38 Irving Moore, Jr Arnold, F P 1139 08/01/39 Anderson, Ira T 1199 11/20/40 Davant & Davant Albert, Felix 1201 12/27/40 C R Bell Alexander, Edith Hawk vs Joe H Hawk 1203 02/02/41 G P Hardy, Jr Anderson, Jr, Ira T 1204 02/12/41 J E Davant Alavarez, Marie et al 1308 01/15/44 W C Gray Aakin, Mary F 1351 01/26/45 D S Prinzing Armstead, James 1368 05/02/45 C A Erickson Arnold, Oscar 1375 06/21/45 W C Gray Antwine, (Antoine) Jefferson, Sr 1391 10/25/45 Chas V Yeamans Allen, Samuel P 1566 08/03/49 Chas V Yeamans Aliniece,John, Jr,Minor 1587 12/15/49 Chas V Yeamans Allen, V W 1599 03/21/50 Chas V Yeamans Arthur, Louise B 1614 07/15/50 Chas V Yeamans Allen, Mary Esther 1619 09/28/50 Chas V Yeamans Arias, Robert,et al Min 1650 05/03/51 Harris & Harris Davant, Owen & Allen, Harley D 1661 07/19/51 Dunnam Adams, Lillie A 1689 01/02/52 Chas V Yeamans Altenburg, J H 1722 07/07/52 J J Spurgeon Aaron, Edward 1745 11/29/52 Stinson, May, et al Ainsworth, David H 1760 03/12/53 George R Keen, Jr Allen, Earl R 1789 09/03/53 Chas V Yeamans Arnold, Frances Dell 1790 09/18/53 Jack H Reeves Arnold, Frances Dell 1791 09/22/53 Eli Mayfield Allen, Amanda 1796 11/02/53 Charles V Yeamans Andis,Edward M, NCM 1798 11/13/53 R F Peden, Jr Andis, Edward M 1799 11/14/53 R F Peden, Jr Atha, Woody W 1807 01/07/54 W E Davant Alcorn, Bess -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

I Thesis/Dissertation Sheet I Australia's -1 Global UNSW University I SYDN�Y I Surname/Family Name Dempsey Given Name/s Claire Kathleen Marsden Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar MPhil Faculty UNSW Canberra I School School of Humanities and Social Sciences Thesis Title 'A quick kiss in the dark from a stranger': Stephen King and the Short Story Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) There has been significant scholarly attention paid to both the short story genre and the Gothic mode, and to the influence of significant American writers, such as Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne and H.P. Lovecraft, on the evolution of these. However, relatively little consideration appears to have been offeredto the I contribution of popular writers to the development of the short story and of Gothic fiction. In the Westernworld in the twenty-firstcentury there is perhaps no contemporary popular writer of the short story in the Gothic mode I whose name is more familiar than that of Stephen King. This thesis will explore the contribution of Stephen King to the heritage of American short stories, with specific reference to the American Gothic tradition, the I impact of Poe, Hawthorneand Lovecrafton his fiction, and the significance of the numerous adaptations of his works forthe screen. I examine Stephen King's distinctive style, recurring themes, the adaptability of his work I across various media, and his status within American popular culture. Stephen King's contribution to the short story genre, I argue, is premised on his attention to the general reader and to the evolution of the genre itself, I providing as he does a conduit between contemporary an_d classic short fiction. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Billy Summers Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wizard and Glass Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End -

Skeleton-Crew-Stephen-King-Use

This book is for Arthur and Joyce Greene I’m your boogie man that’s what I am and I’m here to do whatever I can ... —K.C. and the Sunshine Band Contents Title Page Dedication Epigraph Introduction The Mist Here There Be Tygers The Monkey Cain Rose Up Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut The Jaunt The Wedding Gig Paranoid: A Chant The Raft Word Processor of the Gods The Man Who Would Not Shake Hands Beachworld The Reaper’s Image Nona For Owen Survivor Type Uncle Otto’s Truck Morning Deliveries (Milkman #1) Big Wheels: A Tale of The Laundry Game (Milkman #2) Gramma The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet The Reach Notes Copyright Page Do you love? Introduction Wait—just a few minutes. I want to talk to you ... and then I am going to kiss you. Wait ... I Here’s some more short stories, if you want them. They span a long period of my life. The oldest, “The Reaper’s Image,” was written when I was eighteen, in the summer before I started college. I thought of the idea, as a matter of fact, when I was out in the back yard of our house in West Durham, Maine, shooting baskets with my brother, and reading it over again made me feel a little sad for those old times. The most recent, “The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet,” was finished in November of 1983. That is a span of seventeen years, and does not count as much, I suppose, if put in comparison with such long and rich careers as those enjoyed by writers as diverse as Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, Mark Twain, and Eudora Welty, but it is a longer time than Stephen Crane had, and about the same length as the span of H. -

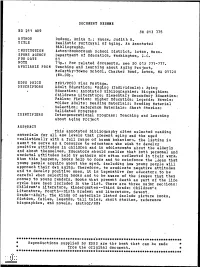

AMBLE Fromteaching and Learning About Aging Project, Mccarthy -Towne School, Charter Road, Acton, MA 01720 ($4.00)

DOCUMENT BESUME ED 211 409 SO 013 775 A UTHOR Dodson, Anita E.; Hause, Judith B. T ITLE Realistic Portrayal of Aging. An Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION Acton-Boxborough School District, Acton, Mass. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, L.,-C,. PUB DATE 81 NOTE 71p.; For related documents, see SO 013 771-777. AVAMBLE FROMTeaching and Learning about Aging Project, McCarthy -Towne School, Charter Road, Acton, MA 01720 ($4.00). DFS PRICE ME01/PC03 Plus Postage. ESCRIPTORS Adult Education: *A.ging (Individuals); Aging Education; Annotated Bibliographies; Biographies: Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education: Fables: Fiction; Higher Education; Legerds; Novels; *Older Adults: Reading Materials; Reading Material Selection; Referenct Materials: Short Stories; Validated Programs IDENTIFIERS Intergenerational Programs; Teaching and Learning about Aging Project ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography cites selected reading materials for all age levels that present agingand the aged realistically with a full range of human behaviors.The listing is meant to serve as a resource to educators who wishtc develop positive attitudes it children and in adolescentsabout the elderly and about themselves. Educators should realize thatboth personal and societal attitudes held by authors are often reflected intheir work. Mhen this happens, books help to form andto reinforce the leas that young people acquire about the aged, including how young people will approach their own aging. Therefore, to eradicate negativeattitudes and to develop positive ones, it is imperative foreducators,to be careful when selecting books and to beaware of the iaages that they convey to young readers. Books that present deathas part of the life cycle have been included in the list.