A General Overview of Waterjet Surface Treatment Modeling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Hammer Arrestors Materials Water Hammer Arrestor Should Be Selected

Sizing and Placement Rule 1 covers multiple fixture branch lines which do not exceed 20 feet length. Series 15M2 Explanation - Fixture unit sizing and selection table is used to Water Hammer Arrestor select the required PDI unit (water hammer arrestor). For Commercial/Residential Systems Riser Up to 20' Rule 1 Typical Branch Line Rule 2 covers multiple fixture branch lines which exceed 20 feet As shown above, it has been established that the preferred location in length. for the water hammer arrestor is at the end of the branch line between Explanation - Fixture unit sizing and selection table is used to the last two fixtures served. select the required PDI unit (water hammer arrestor). The sum of The location of the water hammer arrestor shown above applies to the fixture unit rating of units X and Y shall be equal to or greater branch lines that do not exceed 20 feet in length, from the start of the than the demand of the branches. horizontal branch line to the last fixture supply on this branch line. When the branch line exceeds the 20 foot length, an additional water Over 20' hammer arrestor should be used. This practice is best defined by two Rule 2 Features rules which have been established to cover the placement of water • NPT solid hex brass adapter or solder end connection hammer arrestors. for easy installation 15M2 • Approved for installation with no access panel required 15M2S • May be installed in new or existing plumbing systems with a standard pipe tee vertically, horizontally or at any angle • PDI Listed (PDI WH201) • Maintenance free – unit piston is the only moving part Selection for Long Piping Runs Sizing Table • Air pre-load is 60 psi (4.2 bar) Pre-charged The majority of sizing and selection applications will involve single and For Water Pressures up to 65psi Air Chamber multiple fixture branch lines. -

Paul Sellers' Workbench Measurements and Cutting

PAUL SELLERS’ WORKBENCH MEASUREMENTS AND CUTTING LIST PAUL SELLERS’ WORKBENCH MEASUREMENTS AND CUTTING LIST NOTE When putting together the cutting list for my workbench, I worked in imperial, the system with which I am most comfortable. I was not happy, however, to then provide direct conversions to metric because to be accurate and ensure an exact fit this would involve providing measurements in fractions of millimetres. When I do work in metric I find it more comfortable to work with rounded numbers, therefore I have created two slightly different sets of measurements. This means that in places the imperial measurement given is not a direct conversion of the metric measurement given. Therefore, I suggest you choose one or other of the systems and follow it throughout. © 2017 – Paul Sellers v2 PAUL SELLERS’ WORKBENCH MEASUREMENTS AND CUTTING LIST WOOD QTY DESCRIPTION SIZE (IMPERIAL) SIZE (METRIC) (THICK X WIDE X LONG) (THICK X WIDE X LONG) 4 Leg 2 ¾” x 3 ¾” x 34 ⅜” 70 x 95 x 875mm 1 Benchtop 2 ⅜” x 12” x 66” 65 x 300 x 1680mm 2 Apron 1 ⅝” x 11 ½” x 66” 40 x 290 x 1680mm 1 Wellboard 1” x 12 ½” x 66” 25 x 320 x 1680mm 4 Rail 1 ½” x 6” x 26” 40 x 150 x 654mm 2 Bearer 1 ¼” x 3 ¾” x 25” 30 x 95 x 630mm 4 Wedge ⅝” x 1 ½” x 9” 16 x 40 x 228mm 4 Wedge retainer ⅝” x 1 ½” x 4” 16 x 40 x 100mm HARDWARE QTY DESCRIPTION SIZE (IMPERIAL) SIZE (METRIC) 1 Vise 9” 225mm Dome head bolts (including nuts and washers) for 4 ⅜” x 5” 10 x 130mm bolting legs to aprons 2 Lag screws (with washers) for underside of vise ½” x 2 ½” 12 x 65mm 2 Lag screws for face -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

Hammer Drill

Hammer Drill 15 mm (9/16”) MODEL HP1501 004187 DOUBLE INSULATION INSTRUCTION MANUAL WARNING: For your personal safety, READ and UNDERSTAND before using. SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS FOR FUTURE REFERENCE. SPECIFICATIONS Model HP1501 Concrete 15 mm (9/16”) Capacities Steel 13 mm (1/2”) Wood 25 mm (1”) No load speed (RPM) 0 - 2,800/min. Blows per minute 0 - 44,800 Overall length 299 mm (11-3/4”) Net weight 1.7 kg (3.7 lbs) • Manufacturer reserves the right to change specifications without notice. • Specifications may differ from country to country. GENERAL SAFETY RULES USA002-2 (For All Tools) WARNING: Read and understand all instructions. Failure to follow all instructions listed below, may result in electric shock, fire and/or serious personal injury. SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS Work Area 3. Keep bystanders, children, and visitors away while operating a power tool. Distrac- 1. Keep your work area clean and well lit. tions can cause you to lose control. Cluttered benches and dark areas invite acci- dents. Electrical Safety 2. Do not operate power tools in explosive 4. Double insulated tools are equipped with atmospheres, such as in the presence of a polarized plug (one blade is wider than flammable liquids, gases, or dust. Power the other.) This plug will fit in a polarized tools create sparks which may ignite the dust outlet only one way. If the plug does not fit or fumes. fully in the outlet, reverse the plug. If it still does not fit, contact a qualified elec- 2 trician to install a polarized outlet. Do not 13. -

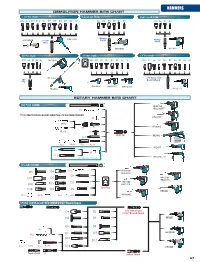

HAMMERS DEMOLITION HAMMER BITS CHART 1-1/8” Hex Shank Makita Large Shank Makita Small Shank D15 D14 D13 D12 D9 D7 D5 D4 D3 D2 D1 D7 D5 D4 D3 D2 D1 D10 D8 D3 D1

HAMMERS DEMOLITION HAMMER BITS CHART 1-1/8” Hex Shank Makita Large Shank Makita Small Shank D15 D14 D13 D12 D9 D7 D5 D4 D3 D2 D1 D7 D5 D4 D3 D2 D1 D10 D8 D3 D1 Makita HM1304B HM1810 Large Makita 1-1/8” Small Hex HM1500 HK1810 SDS Plus Shank SDS Max Shank 3/4” Hex Shank D10 D8 D3 D2 D1 HK1820 D9 D7 D6 D5 D4 D3 D2 D1 D16 D11 D9 D7 D6 D5 D4 D3 D2 D1 SDS max HK1820L 3/4” Hex 21/32” SDS Round Shank Plus HM0860C HM1100C HM1202C HK0500 HM1211B ROTARY HAMMER BITS CHART SDS PLUS SHANK HR3210C R1 HR3210FCT R8 IS ADAPTER WHICH ALLOWS OLDER TOOLS TO USE DEMOLITION BITS R6 HR2811F Metal R3 R2 HR3000C Wood R4 SDS Plus HR2432 D1 R23c R23b R23 R23a HR2455 R9 R8 R10 HR2470F / FT HR160DWA & HR2400 only SDS MAX SHANK D4 R1a HR5210C D5 HR5211C D1 D11 D6 HR4010C SDS HR4011C D2 HR4510C D16 D15 max HR4511C SDS Max D18 D9 D3 HR4002 R24c R24b R24 R24a HR4500C SPLINE SHANK & 3/4” HEX SHANK 21/32” Round Shank D4 D2 3/4” HEX Shank 21/32” Round Shank D5 D3 HR3851 D8 D6 R6 D7 HR4040C R1b D1 D18 D17 R24a R24c R24b R24 D16 HR5000 Taper Shank R5 Spline Shank 67 HAMMERS DEMOLITION HAMMER BITS CHART Demolition Hammer Bits Chart HM1202C, HM1100C, HR3210C/FCT, HM0860C, HR5210C, HR3000C, HR2811F, HR5211C, HR4510C, HM1810C, HM1304B HM1500 HK1810 HR2455, HR2432, Model HR4511C, HR4500C, HR2470F/FT, HK1820, HR4010C, HR4011C, HK0500 HR4002 Ref. No. Description 1-1/8" Hex 3/4" Hex Makita Large Makita Small SDS Plus 3/4" Hex, 21/32" Round SDS Max Hex Shank Size Part No. -

The Leading Manufacturer of Forged Hand and Power Tools Accessories Since 1946

122806_A_AJAX_ATW-lisa 7/17/12 8:20 PM Page 1 The Leading Manufacturer of Forged Hand and Power Tools Accessories Since 1946 TM Phone: 800.323.9129 • Fax: 800.424.2529 122806_A_AJAX_r3.qxp_AJAX 7/25/12 11:59 AM Page 3 Phone: 800.323.9129 • Fax: 800.424.2529 www.ajaxtools.com ZIP GUN CHISELS & ACCESSORIES WELD FLUX CHISELS & ACCESSORIES CHIPPING HAMMER TOOLS & ACCESSORIES BERYLLIUM COPPER SAFETY TOOLS RIVET BUSTER TOOLS & ACCESSORIES PAVING BREAKER TOOLS DRILL STEEL TOOLS ELECTRIC HAMMER TOOLS RIGGER TOOLS HAND TOOLS WEDGES, LINE UP PINS & SCRAPERS DEMOLITION TOOLS TM Wear Safety Goggles 4 122806_A_AJAX_ATW-lisa 7/17/12 8:20 PM Page 5 23⁄8" 3 .495" 111⁄16" .495" 2 ⁄8" 60mm 51⁄64" 15⁄16" 60mm 13⁄4" 17 ⁄32" .485" 44.4mm .580" 15⁄32" .469" 14.7mm .576" .680" .680" .576" 17.2mm 17.2mm .812" .812" 3 3 20.6mm 2 ⁄8" 3⁄8" 13 9 20.6mm 23⁄8" ⁄8" 60.3mm ⁄16" ⁄16" .495" 19⁄32" 29⁄32" 9.5mm 9.5mm 60.3mm 3 4 1⁄2" sq. 1⁄4" 1⁄4" 1 ⁄ " .360" Ø .415" 44.4mm .580" .425" 1 14.7mm Ø .373" .576" 1 ⁄8" .680" 13⁄16" 11⁄8" 13⁄16" 28.5mm 17.2mm 20.6mm 28.5mm 20.6mm 21⁄2" 1 4 21⁄2" 11⁄4" 1 5 1 ⁄ " 3⁄8" 63.5mm 3 1 ⁄4" REF 1 ⁄64" 32mm 63.5mm 32mm ⁄8" .620" 9.5mm 13⁄4" 9.5mm .354" .919" 1" 3⁄8" .375" .610" 44.4mm 13 13 .576" .680" -

How to Use Tools / Mistakes to Avoid CARLTSOE SAFETY TOOLS

CARLTSOE SAFETY TOOLS If you just had the right tools How to Use Tools / Mistakes to Avoid Tool Proper Uses Abuse/Misuse Nail Hammers Nail hammers are intended for driving and pulling common, Never strike one hanmmer with or against another hammer unhardened nails only, and for ripping apart wooden or a hatchet. Never strike nail pullers, steel chisels or structures. They may be used to strike nail sets with the other hardened objects with a nail hammer as the face may center of the striking face. chip, possibly resulting in eye or other serious injury. Ball Pein Hammers Ball pein hammers of the proper size are designed for striking chisels and punches, and for riveting, shaping and Strike squarely and avoid glancing blows that may cause straightening unhardened metal. the edge of the face to chip, possibly resulting in eye or When striking a struck tool (chisel or punch), the striking face other serious injury. Never strike with or against the side, of the hammer should have a diameter at least 3/8" larger or cheek, of any hammer. than the struck face of the tool. Riveting and Setting Hammers The Riveting hammer is designed for driving and spreading Never use these special-purpose hammers for general- rivets on sheet metal work. The Setting hammer is designed purpose work. The square, sharp edges of the setting for forming sharp corners, closing and peining seams and lock hammer make it vulnerable to chipping if improperly used. edges, and for use by glaziers for inserting glazier points. Never strike against other steel tools. -

User Manual Bandsaw N4400

User Manual (Translation) Bandsaw N4400 Keep this manual handy and in good condition for continual reference! Dok.ID: 503-15-4502 • Englisch • 2010-10-01 Bandsaw N4400 Attention: Upon arrival, the machine must be inspected immediately. If the machine was damaged during transport or if parts are missing, a written record of the problems must be submitted to the forwarding agent and a damage report must be drawn up. Be sure to also notify your supplier straight away. For the safety of all personnel, it is necessary to conscientiously study this manual before assembling and putting the machine into operation. This manual must be kept in good condition, as it is considered to be a part of the machine. Furthermore, keep the manual handy in the vicinity of the machine so that it is acces- sible to personnel when they are using, maintaining or repairing the machine. HAMMER A product of the FELDER GROUP © Felder KG KR-FELDER-STR 1 A-6060 Hall in Tirol Tel.: +43 (0) 5223 45 0 90 Fax.: +43 (0) 5223 45 0 99 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.hammer.at 2 Bandsaw N4400 Table of contents Table of Contents 1 General .......................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Explanations of the symbols .............................................................................................5 1.2 Information regarding the manual ....................................................................................5 1.3 Liability and warranty .....................................................................................................6 -

100002768 Catalog.Pdf

AMERICA’S FIRST AND FINEST SOLID STEEL STRIKING TOOLS SINCE 1923 ESTWING TOOLS NOW WITH THE WORLD’S BEST SHOCK REDUCTION GRIPS CATALOG NO. 06.2007 FULL LINE TOOL CATALOG TOOL LINE FULL Since 1923, the Estwing family has taken pride in designing and manufacturing the world’s most durable, comfortable and attractive striking tools. All claw hammers, axes, specialty tools and pry bars are manufactured to the highest possible standards and offer a true value to both tradesmen and craftsmen alike. Today Estwing’s shock reduction grip provides our customers with the best available grip for reducing vibrations caused by impact. Plus, this grip offers the utmost in both comfort and durability. This patented Estwing innovation is sure to be the standard for ergonomically correct hammers for decades to come. All of our nylon vinyl grip tools are now being made with this new material. Comfort, durability and dependability are the foundation of our proud tradition. We hope you will put this proud tradition to work for you! Made in the U.S.A. TABLE OF CONTENTS NAIL HAMMERS 5-10 AXES & WOOD SPLITTING TOOLS 11-13 BRICKLAYER HAMMERS 14-16 SPECIALTY TOOLS 17-19 DRYWALL HAMMERS 20-21 HATCHETS & ROOFING TOOLS 22-25 PRY BARS 26-29 GEOLOGICAL TOOLS 30-37 CHISELS, PUNCHES & NAIL SETS 38-40 SOFT FACE HAMMERS 41-43 INTERNATIONAL HAMMERS 44-47 SURE STRIKE HAMMERS 48-54 MERCHANDISERS 55 PROPER USE AND SAFETY INSTRUctIONS Proper Tool Use and Safety Instructions: Always use the correct tool for the job! Always wear safety goggles when using striking or struck tools. -

Pneumatic Chipping Hammer #550640, JCT-3640 #550641, JCT-3641 #550642, JCT-3642 #550643, JCT-3643 #550644, JCT-3644 #550645, JCT-3645

Pneumatic Chipping Hammer #550640, JCT-3640 #550641, JCT-3641 #550642, JCT-3642 #550643, JCT-3643 #550644, JCT-3644 #550645, JCT-3645 Operation & Parts Manual M-550640 Edition 4 11/2018 JET 427 New Sanford Road LaVergne, TN 37086 Ph.: 800-274-6848 www.jettools.com Copyright © 2017 JET Safety warnings General air tool warnings 12. Do not operate this tool while tired or under the influence of drugs, alcohol, or any 1. Read and understand this entire manual medication. before attempting assembly or operation. 13. Adopt a comfortable posture with proper 2. Read and understand all warnings posted on balance, and maintain secure footing at all the tool and in this manual. Failure to comply times. Non-slip footwear or anti-skid floor with all of these warnings may cause serious strips are recommended. injury. 14. Do not wear loose clothing or jewelry. Confine 3. Replace warning labels if they become long hair. obscured or removed. 15. Excessive air pressure and too much free 4. Do not use this tool for other than its intended rotation may decrease life of the tool and may use. If used for other purposes, JET disclaims cause a hazardous situation. any real or implied warranty and holds itself harmless from any injury that may result from 16. Check air hoses for wear, and keep them that use. away from heat and sharp edges. Repair or replace damaged air hose immediately. Do 5. Always wear ANSI Z87.1 approved safety not carry tool by the air hose. glasses or face shield while using this tool. -

CLASSIC WORKBENCH Design, Construction Notes & Techniques

BENCHCRAFTED CLASSIC WORKBENCH Design, Construction Notes & Techniques Copyright, Benchcrafted December 2016 www.benchcrafted.com 1 DESIGN When we set out to design a new workbench for our customers, from the very beginning we decided it should, above all, be simple. Not only in function, but also to build. We make no bones about it, our vises are designed and made to work sweetly, but not to a price point. However, not everyone is ready for their ultimate Split Top Roubo bench build, either monetarily, or technically. For those looking to get their feet wet in traditional woodworking, using time-proven techniques and tools, this bench will provide all the workholding required to test the waters. For many, this will be all the bench you need, and for others it will be an excellent springboard to our Split Top Roubo, while keeping the Classic as a second bench. The Classic Workbench is based largely on the famous Plate 11 workbench from Roubo’s “The Art of the Joiner”. We’ve built dozens of these “Roubo” benches over the past decade, helped others build hundreds more and examined extant French benches from the period. We’ve haven’t changed our opinion on this fundamental design. The Classic is a simpler, easier to build version of Roubo’s Plate 11 bench that captures all the functionality of Roubo’s design. French technical schools of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were outfitted with benches just like this. Paring down the bench to its essentials, we’ve incorporated our Classic Leg Vise, Planing Stop and Holdfast as workholding devices. -

PUNCHES and CHISELS Punches and Chisels the Anvil End on Heads of Snap-On® Punches and Chisels Are Machined to a Modified Parabolic Curve

PUNCHES AND CHISELS Punches and Chisels The anvil end on heads of Snap-on® punches and chisels are machined to a modified parabolic curve. This design directs the striking force to the center of the tool head to allow slow metal displacement. The parabolic curve controls mushrooming to reduce chipping and splitting. Heads should be re-dressed to their original shape with hand files as necessary. The tough steel alloy is machined and differentially heat treated for optimum performance. The hardness of the striking head is reduced to help toughness and add qualities that result in a slower mushrooming of the striking surface. PPC250BK Punch and Chisel Set. PPC100AK Punch and Chisel Set. ncludes 24 pcs. in KB2179 kit bag: Includes 10 pcs. in KB2175 kit bag: PPC1A PPC106A PPC205A PPC820B PPC812B PPC828B PPC15B PPC3A PPC108A PPC206A PPC824B PPC816B PPC12B PPC19B PPC250BK PPC4A PPC110A PPC208A PPC12B PPC820B PPC13B PPC103A PPC112 PPC210A PPC14B PPC824B PPC14B PPC104A PPC203A PPC812B PPC15B PPC100AK PPC105A PPC204A PPC816B PPC19B PPCD70BK Punch and Chisel Set. PPC210BK Punch and Chisel Set. Includes 7 pcs. in KB2183 kit bag: Includes 22 pcs. in KB2178 kit bag: PPC103A PPC106A PPC110A PPC1A PPC105A PPC204A PPC816B PPC104A PPC107A PPC5A PPC106A PPC205A PPC820B PPC105A PPC108A PPC3A PPC108A PPC206A PPC824B PPC210BK PPC4A PPC110A PPC208A PPC828B PPC103A PPC112 PPC210A PPCD70BK PPC104A PPC203A PPC812B PPCS60BK Punch and Chisel Set. Includes 6 pcs. in KB2185 kit bag: PPC715BK Punch and Chisel Set. PPC203A PPC205A PPC208A Includes 16 pcs. in KB2182 kit bag: PPC204A PPC206A PPC210A PPC1A PPC104A PPC203A PPC208A PPC3A PPC105A PPC204A PPC812B PPC4A PPC106A PPC205A PPC816B PPC715BK PPC103A PPC108A PPC206A PPC820B PPCS60BK PPC50AK Punch and Chisel Set.