Incapacity Benefit Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies

1 From mountain to sea Aberdeenshirep Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies December 2017 2 | Contents 1 BENEFITS 3 2 CHILDCARE AND RESPITE 23 3 COMMUNITY ACTION 43 4 COMPLAINTS 50 5 EDUCATION AND LEARNING 63 6 Careers 81 7 FINANCIAL HELP 83 8 GENERAL SUPPORT 103 9 HEALTH 180 10 HOLIDAYS 194 11 HOUSING 202 12 LEGAL ASSISTANCE AND ADVICE 218 13 NATIONAL AND LOCAL SUPPORT GROUPS (SPECIFIC CONDITIONS) 223 14 SOCIAL AND LEISURE OPPORTUNITIES 405 15 SOCIAL WORK 453 16 TRANSPORT 458 SEARCH INSTRUCTIONS 1. Right click on the document and select the word ‘Find’ (using a left click) 2. A dialogue box will appear at the top right hand side of the page 3. Enter the search word to the dialogue box and press the return key 4. The first reference will be highlighted for you to select 5. If the first reference is not required, return to the dialogue box and click below it on ‘Next’ to move through the document, or ‘previous’ to return 1 BENEFITS 1.1 Advice for Scotland (Citizens Advice Bureau) Information on benefits and tax credits for different groups of people including: Unemployed, sick or disabled people; help with council tax and housing costs; national insurance; payment of benefits; problems with benefits. http://www.adviceguide.org.uk 1.2 Attendance Allowance Eligibility You can get Attendance Allowance if you’re 65 or over and the following apply: you have a physical disability (including sensory disability, e.g. blindness), a mental disability (including learning difficulties), or both your disability is severe enough for you to need help caring for yourself or someone to supervise you, for your own or someone else’s safety Use the benefits adviser online to check your eligibility. -

Notes About Claiming Carer's Allowance

Carer’s Allowance Notes Carer’s Allowance gives fnancial help to people who cannot take up full-time paid work as they provide regular care to a disabled person. The quickest and easiest way to claim Carer’s Allowance is online. Check if you can get Carer’s Allowance and make a claim at www.gov.uk/carers-allowance We have many different ways we can communicate with you If you would like us to communicate with you by braille, British Sign Language, a hearing loop, translations, large print, audio or something else please contact us. You can find our contact details by searching for the relevant benefit on GOV.UK About these notes • These notes tell you more about Carer’s Allowance • They tell you how Carer’s Allowance might affect other benefts that you or the person you provide care for are getting • You can check if you might get Carer’s Allowance by using an easy checklist on page 2 of this booklet. If you cannot get Carer’s Allowance, go to www.gov.uk to see what other help you might be able to get About the form • Use the form to claim Carer’s Allowance • You, the carer, should fll in the form, not the person you provide care for. • Please fll in the form with BLACK INK and in CAPITALS • Please answer all the questions and send us all the documents we ask for • Contact us if you cannot fll in the form or send us the documents we ask for, because this might delay your claim • The form and these notes are available in Welsh, large print or braille. -

Benefit and Pension Rates 2020 to 2021

Benefit and Pension Rates 2020/2021 RATES RATES (Weekly rates unless otherwise shown) 2019 2020 ATTENDANCE ALLOWANCE higher rate 87.65 89.15 low er rate 58.70 59.70 BEREAVEMENT BENEFIT (for deaths between 11 April 1998 & 5 April 2017) Widowed Parents Allowance 119.90 121.95 BEREAVEMENT SUPPORT PAYMENT (for deaths occurring on or after 6 April 2017) Standard rate (lump sum) 2500.00 2500.00 Standard rate monthly payments 100.00 100.00 Higher rate (lump sum) 3500.00 3500.00 Higher rate monthly payments 350.00 350.00 BENEFIT CAP - Rates introduced November 2016 Reduction in annual level of Benefit Cap (Greater London) Couples (with or without children) or single claimants with a child of qualifying age 23000.00 23000.00 Single adult households without children 15410.00 15410.00 Reduction in annual level of Benefit Cap (Rest of Great Britain) Couples (with or without children) or single claimants with a child of qualifying age 20000.00 20000.00 Single adult households without children 13400.00 13400.00 Monthly equivalent (Greater London) Couples (with or without children) or single claimants with a child of qualifying age 1916.67 1916.67 Single adult households without children 1284.17 1284.17 Monthly equivalent (Rest of Great Britain) Couples (with or without children) or single claimants with a child of qualifying age 1666.67 1666.67 Single adult households without children 1116.67 1116.67 Weekly equivalent (Greater London) Couples (with or without children) or single claimants with a child of qualifying age 442.31 442.31 Single adult households -

Pulling in Different Directions? the Impact of Economic Recovery and Continued Changes to Social Security on Health and Health Inequalities in Scotland

Pulling in different directions? The impact of economic recovery and continued changes to social security on health and health inequalities in Scotland Martin Taulbut, Wendy Hearty, Fiona Myers, Neil Craig and Gerry McCartney 2016 We are happy to consider requests for other languages or formats. Please contact 0131 314 5300 or email [email protected] Research undertaken June 2014–October 2015. This document should be cited as: Taulbut M, Hearty W, Myers F, Craig N, McCartney G. Pulling in different directions? The impact of economic recovery and continued changes to social security on health and health inequalities in Scotland. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland; 2016 Published by NHS Health Scotland 1 South Gyle Crescent Edinburgh EH12 9EB © NHS Health Scotland 2016 All rights reserved. Material contained in this publication may not be reproduced in whole or part without prior permission of NHS Health Scotland (or other copyright owners). While every effort is made to ensure that the information given here is accurate, no legal responsibility is accepted for any errors, omissions or misleading statements. NHS Health Scotland is a WHO Collaborating Centre for Health Promotion and Public Health Development. Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 2 Selected glossary of terms ......................................................................................... 3 Executive summary ................................................................................................... -

Changes to Pay Periods and Pay Week-Ending Days

Changes to pay periods and pay week-ending days Summary of the changes From 6 April 2009 Jobcentre Plus will introduce important changes for the majority of customers receiving working age benefits. Instead of receiving different benefits on different days people will have one pay week-ending day allocated to them that is determined by their National Insurance number. Also, payments will normally be made a minimum of fortnightly in arrears instead of the current situation where some benefits are paid weekly and others fortnightly. The aim of this is to simplify the benefits system as people will retain the same pay week- ending day whichever benefit they are awarded from Jobcentre Plus. The following sections give more details of the changes and how they may affect you. Please use the links below to navigate to the top of the relevant page…… Working age benefit customers included in the changes Notification of the changes Pay week-ending day and pay period explained Pay week-ending day changes If you are moving from payment in advance to payment in arrears Non-recoverable compensation payment Illustration of moving from payment in advance to payment in arrears If you are moving from receiving payments weekly in arrears to fortnightly in arrears Recoverable payment Illustration of moving from weekly in arrears to fortnightly in arrears If only your pay week-ending day is changing Weekly Payments Conversion Procedures Jobseeker's Allowance When will my benefit award for Jobseeker’s Allowance be converted? If only your pay week-ending -

Local Authority Breakdown: Incapacity Benefits and Disability Living Allowance Claimants with Main Condition of Alcohol Or Drug Abuse - Update

Local Authority Breakdown: Incapacity Benefits and Disability Living Allowance claimants with main condition of alcohol or drug abuse - Update July 2012 Background Incapacity benefits are weekly payments for people who become incapable of work while under State Pension age. They are: Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), which is for new claimants from October 2008, offers personalised support and financial help, so that claimants can do appropriate work, if they are able to, and provides increased financial support for those who have an illness or disability that severely affects their ability to work. Incapacity Benefit (IB) provides support for people who cannot work because of an illness or disability which started before October 2008. Similarly, Severe Disablement Allowance (SDA) could be claimed before April 2001 by those unable to work for at least 28 weeks in a row because of illness or disability. IB and SDA are being phased out, and work is underway to review claims of those under state pension age to see if they can claim ESA instead. Disability Living Allowance (DLA) is a non-means-tested benefit that provides a cash contribution towards the extra costs of needs arising from an impairment or health condition. From 2013 the Government is proposing to replace DLA with a new benefit called Personal Independence Payment to support disabled working age people with the greatest needs and help them live more independently. More information on incapacity benefits and DLA is available on the DirectGov website at http://www.direct.gov.uk/en/DisabledPeople/FinancialSupport/esa/DG_171894 and http://www.direct.gov.uk/en/MoneyTaxAndBenefits/BenefitsTaxCreditsAndOtherSupport/Di sabledpeople/DG_10018702 . -

Are You Claiming Free Prescriptions?

Are you claiming free prescriptions? Don’t assume you’re entitled. You could have to pay up to £100 – as well as your prescription charge. Check before you tick What entitles you to free NHS prescriptions? Your age You’re entitled to free prescriptions if you’re: • under 16 • 16, 17, or 18 and in full-time education • 60 or over Students aged 19 and over aren’t automatically entitled to free prescriptions, but can apply for help through the NHS Low Income Scheme (see page 6). Certain benefits Not all benefits entitle you to free prescriptions. Check which type of benefit you get before you tick the back of your prescription. You’re entitled to free prescriptions if you are named on a claim for: • Income Support • income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance • income-related Employment and Support Allowance • Pension Credit (Guarantee Credit) paid on its own, or Pension Credit (Guarantee Credit with Savings Credit) • certain Tax Credits - see page 4, under ‘NHS Tax Credit Exemption Certificate’ • Universal Credit - but only if your earnings in your last assessment period were £435 or less, or £935 or less if you get an element for a child or have limited capability for work 2 You’re not entitled to free prescriptions if you are named on a claim for: • contribution-based Jobseeker’s Allowance, paid on its own • contribution-based Employment and Support Allowance, paid on its own • Pension Credit (Savings Credit), paid on its own • any benefit paid on its own and not listed in the green box opposite (such as Disability Living Allowance, Personal Independence Payment or Incapacity Benefit) Certificates You’re entitled to free NHS prescriptions if you have one of these certificates and it is still valid. -

Your Social Security Rights in United Kingdom

Your social security rights in the United Kingdom European Commission Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities Your social security rights in the United Kingdom The information provided in this guide has been drafted and updated in close collaboration with the national correspondents of the Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC). The MISSOC-Network, coordinated since 1990 by the European Commission, comprises up to two official representatives of the public administrations of 31 European countries (the 27 EU Member States, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Iceland). MISSOC produces regularly updated information and analyses which are mainly used by officials, researchers and people moving within Europe. More information on the MISSOC network is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=815 This guide does not provide an exhaustive description of the social security arrangements applicable in this country. For more detailed information on social security in this and other European countries, please refer to the MISSOC Comparative Tables, the MISSOC Charts and Descriptions of the Organisation of Social Protection and to the MISSOC Annex on Social Protection for the Self-employed, all available at the abovementioned link. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission may be held responsible for the use that may be made of the information contained in this publication. © European Union, 2011 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. 2 December 2010 European Commission Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities Your social security rights in the United Kingdom Chapter I: Introduction, organisation and financing.....................................................5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 5 Organisation of social protection............................................................................................... -

Factsheet 55: Carer's Allowance

Factsheet 55 Carer's Allowance May 2021 About this factsheet This factsheet explains what Carer’s Allowance is, the eligibility criteria, and how to make a claim. It explains how Carer’s Allowance may affect any other benefits you, or the person you care for, are receiving, and what to do if you have a change of circumstance. The information in this factsheet is correct for the period May 2021 to April 2022. Benefit rates are reviewed annually and take effect in April but rules and figures can sometimes change during the year. The information in this factsheet is applicable in England, Scotland and Wales. If you are in Northern Ireland, please contact Age NI for information. Contact details can be found at the back of this factsheet. Coronavirus: Some rules in this factsheet may be affected by changes or easements related to Covid-19. For the latest information see www.ageuk.org.uk/coronavirus-benefits Contact details for any organisation mentioned in this factsheet can be found in the Useful organisations section. Page 1 of 18 Contents 1 What is Carer’s Allowance? 4 2 Current rate 4 3 Who can claim? 4 3.1 How do you qualify? 4 4 Making a claim 6 4.1 Backdating and advance claims 6 5 Decisions and payments 6 5.1 Challenging decisions 6 5.2 Payment 7 6 Change of circumstances 7 6.1 If the person you care for goes into a care home or hospital 7 6.2 If the person you care for dies 8 6.3 Breaks from caring 8 6.4 Going abroad 8 6.4.1 Temporary absence abroad 8 6.4.2 Exporting Carer’s Allowance 9 6.5 Invalid Care Allowance 9 7 Other benefits -

Disability Benefits

Disability benefits Disability benefits are one of the areas on which the Government is focusing its root and branch review of social security policy. Richard Berthoud of the University of Essex has reviewed research on the role of social security in the lives of disabled people. His review shows that: The cost of disability benefits has increased fourfold in 18 years. This has been caused more by a rise in the number of disabled claimants than by any improvement in the generosity of the available benefits. The growth in the number of disabled people claiming because they were out of work was not caused by a rise in the number of initial claims, but by an increase in the length of time individuals remained on benefit. The same trend occurred in all age-groups, not just the over-50s. Disabled people may have been affected by a much wider and systematic shift in employment patterns. As the supply of labour has expanded faster than demand, employers have become more selective in their choice of staff. Marginal workers, such as disabled people, have been excluded. The number of people who lost entitlement after Incapacity Benefit rules were tightened up was less than expected. Preliminary evidence suggests that very few of them found a job, and the question remains whether they were ‘capable of work’. Recent evidence suggests that perhaps one-tenth of those receiving Disability Living Allowance may not be entitled to it. But underclaiming is at least as important as overclaiming. Both of the main types of disability benefits seem to have gradually extended further down the scale of severity over the years. -

ESA JSA JSAPS Dialogue Code Card

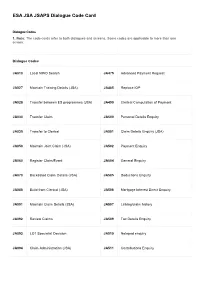

ESA JSA JSAPS Dialogue Code Card Dialogue Codes 1. Note: The code cards refer to both dialogues and screens. Some codes are applicable to more than one screen. Dialogue Codes JA010 Local NINO Search JA475 Advanced Payment Request JA027 Maintain Training Details (JSA) JA485 Replace IOP JA028 Transfer between ES programmes (JSA) JA490 Clerical Computation of Payment JA030 Transfer Claim JA500 Personal Details Enquiry JA035 Transfer to Clerical JA501 Claim Details Enquiry (JSA) JA050 Maintain Joint Claim (JSA) JA502 Payment Enquiry JA060 Register Claim/Event JA504 General Enquiry JA070 Backdated Claim Details (JSA) JA505 Deductions Enquiry JA086 Build from Clerical (JSA) JA506 Mortgage Interest Direct Enquiry JA091 Maintain Claim Details (JSA) JA507 Linking/claim history JA092 Review Claims JA509 Tax Details Enquiry JA093 LO1 Specialist Decision JA510 Notepad enquiry JA094 Claim Administration (JSA) JA511 Contributions Enquiry JA095 Current Work (JSA) JA512 NI Credit Detail Enquiry JA096 P45 Tax Details JA513 Suspension and AR Decision Enquiry JA097 Maintain Revised Contributions (JSA) JA516 Training Enquiry (JSA) JA099 Record Claim Termination Details JA523 Award Details Enquiry JA100 Taxation Changes JA527 Enquire PJA Details (JSA) JA102 Maintain PAYE Reference JA530 Case Controls JA110 Maintain Notepad JA535 Explanation and Reconsideration’s Enquiry JA120 Event Maintenance JA540 Maintain IB & IS Awards (ESA) JA130 Maintain Sensitivity JA570 Enquiry: Notification JA200 Award and Decision JA580 Request DPA Print JA210 Maintain Suspension -

Incapacity Benefit Help If You’Re Too Ill Or Disabled to Work

Incapacity Benefit Help if you’re too ill or disabled to work Part of the Department for Work and Pensions Are you too sick or disabled to work? If the answer is yes, you should read this leaflet. It will tell you about Incapacity Benefit. It will also tell you about the extra help and support you can get while you are off work and when you are ready to return to work again. Incapacity Benefit Contents About Incapacity Benefit What is Incapacity Benefit? ...................... 7 Can I get Incapacity Benefit?.................... 7 State Pension age.................................... 8 How is my benefit worked out?................ 8 How much will I get?................................ 9 Does my age affect how much I get?....... 9 Do I have to pay tax on my Incapacity Benefit? ................................. 10 How do you pay my Incapacity Benefit? ................................. 11 What if I want someone to collect my Incapacity Benefit for me? ................ 11 Will I have to have an interview about work?........................................... 12 What if I can’t get Incapacity Benefit?...... 12 Your sickness or disability What is ‘incapacity for work’? ................ 13 How do I prove I am too sick to work?..... 13 What is the ‘own-occupation test’?........ 14 3 What if I am sick for more than 28 weeks? ............................................. 14 What will happen in the medical check?.... 15 What happens after my medical check? ... 15 If you think our decision is wrong ........... 16 Is a medical check always needed? ....... 16 What if I am terminally ill? ....................... 17 What if I have a mental-health problem?.... 17 What happens if I get better or worse? ...