An Exploration of Smetana's Z Domoviny (From My Homeland)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gustav Mahler : Conducting Multiculturalism

GUSTAV MAHLER : CONDUCTING MULTICULTURALISM Victoria Hallinan 1 Musicologists and historians have generally paid much more attention to Gustav Mahler’s famous career as a composer than to his work as a conductor. His choices in concert repertoire and style, however, reveal much about his personal experiences in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his interactions with cont- emporary cultural and political upheavals. This project examines Mahler’s conducting career in the multicultural climate of late nineteenth-century Vienna and New York. It investigates the degree to which these contexts influenced the conductor’s repertoire and questions whether Mahler can be viewed as an early proponent of multiculturalism. There is a wealth of scholarship on Gustav Mahler’s diverse compositional activity, but his conducting repertoire and the multicultural contexts that influenced it, has not received the same critical attention. 2 In this paper, I examine Mahler’s connection to the crumbling, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century depiction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as united and question whether he can be regarded as an exemplar of early multiculturalism. I trace Mahler’s career through Budapest, Vienna and New York, explore the degree to which his repertoire choices reflected the established opera canon of his time, or reflected contemporary cultural and political trends, and address uncertainties about Mahler’s relationship to the various multicultural contexts in which he lived and worked. Ultimately, I argue that Mahler’s varied experiences cannot be separated from his decisions regarding what kinds of music he believed his audiences would want to hear, as well as what kinds of music he felt were relevant or important to share. -

Event. Location

12th Annual A remarkable CHAMBER EVENT. MUSIC FESTIVAL A remarkable of the LOCATION. BLUEGRASS 2018 Overview Festival Program Now in its 12th year, the FRIDAY, MAY 25, 2018 Chamber Music Festival of the Bluegrass is a premier The Meeting House Central Kentucky cultural destination. Join CMS Artistic Directors David Haydn Finckel and Wu Han for Trio in C major for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Hob. XV:27 (1797) special performances in the Allegro 1820 Meeting House and the Wu Han, Huang, Finckel Meadow View Barn. Chamber music enthusiasts will also Schumann enjoy two educational lectures, Quartet in E-flat major for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Cello, Op. 47 (1842) led by Patrick Castillo, Andante cantabile exploring the history of each Wu Han, Keefe, Lipman, Atapine featured piece of music. Waxman 2018 ARTISTS Carmen Fantasie for Viola and Piano (1947) Lipman, Pohjonen JUHO POHJONEN, Piano WU HAN, Piano Brahms Trio in E-flat major for Horn, Violin, and Piano, Op. 40 (1865) PAUL HUANG, Violin Finale: Allegro con brio ERIN KEEFE, Violin Vlatkovic, Pohjonen MATTHEW LIPMAN, Viola DMITRI ATAPINE, Cello DAVID FINCKEL, Cello RADOVAN VLATKOVIC´ , Horn Friday, May 25 at 6:30pm: Patrons’ Gala and Dinner 12th Annual CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL of the BLUEGRASS SATURDAY, MAY 26, 2018 AT 11:00 AM Dvorák, 14’ SUNDAY, MAY 27, 2018 AT 5:00 PM THE MEETING HOUSE Drobnosti (Miniatures) for Two Violins and Viola, MEADOW VIEW BARN Op. 75a (1887) Haydn, 16’ Cavatina: Moderato Mozart, 26’ Trio in C major for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Capriccio: Poco allegro Quartet in G minor for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Hob. -

The Arctic Is... a Homeland Page 1 Cycles As They Follow the Animals with Which Their Lives Are Closely Involved

A HOMELAND landscape and people It is late winter and the temperature is minus 40 degrees Celsius. The sea is frozen over for a mile from the shore. Far out on the ice a solitary hunter inches forwards towards a seal which has come up for air through a hole in the ice and is resting on the surface. In front of him he pushes a rifle hidden behind a white screen of canvas. There is no sign that there is anyone hidden behind the screen, except for a small cloud of condensation above him as he breathes. If he is skilful and lucky, the seal will not notice him until it is too late. Meanwhile, thousands of miles away inland, three reindeer herders wait on a windswept hilltop, scanning the surrounding mountains with binoculars. In the distance, they see two other herders riding reindeer and weaving their way through the thin larch trees which seem drawn with black ink against the snow on the ground. They have found part of the herd and are driving it toward the waiting men. At last, the sound of men whistling and deer grunting can be heard. The first reindeer filter through the Figure 1 Kyrnysh-Di forest island near surrounding trees, the camouflage of their fur blending closely with the Kolva-Vis river, Nenets Autonomous snow and the tress’ rough, grey-brown bark. Suddenly, the waiting men District.Photo taken by Joachim Otto Habeck, May 1999 burst into action with their lassos, separating some deer and bunching others in order to drive them off later to different pastures. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

1718Studyguidetosca.Pdf

TOSCA An opera in three acts by Giocomo Puccini Text by Giacosa and Illica after the play by Sardou Premiere on January 14, 1900, at the Teatro Constanzi, Rome OCTOBER 5 & 7, 2O17 Andrew Jackson Hall, TPAC The Patricia and Rodes Hart Production Directed by John Hoomes Conducted by Dean Williamson Featuring the Nashville Opera Orchestra CAST & CHARACTERS Floria Tosca, a celebrated singer Jennifer Rowley* Mario Cavaradossi, a painter John Pickle* Baron Scarpia, chief of police Weston Hurt* Cesare Angelotti, a political prisoner Jeffrey Williams† Sacristan/Jailer Rafael Porto* Sciarrone, a gendarme Mark Whatley† Spoletta, a police agent Thomas Leighton* * Nashville Opera debut † Former Mary Ragland Young Artist TICKETS & INFORMATION Contact Nashville Opera at 615.832.5242 or visit nashvilleopera.org. Study Guide Contributors Anna Young, Education Director Cara Schneider, Creative Director THE STORY SETTING: Rome, 1800 ACT I - The church of Sant’Andrea della Valle quickly helps to conceal Angelotti once more. Tosca is immediately suspicious and accuses Cavaradossi of A political prisoner, Cesare Angelotti, has just escaped and being unfaithful, having heard a conversation cease as she seeks refuge in the church, Sant’Andrea della Valle. His sis - entered. After seeing the portrait, she notices the similari - ter, the Marchesa Attavanti, has often prayed for his release ties between the depiction of Mary Magdalene and the in the very same chapel. During these visits, she has been blonde hair and blue eyes of the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca, observed by Mario Cavaradossi, the painter. Cavaradossi who is often unreasonably jealous, feels her fears are con - has been working on a portrait of Mary Magdalene and the firmed at the sight of the painting. -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

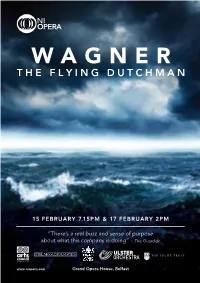

There's a Real Buzz and Sense of Purpose About What This Company Is Doing

15 FEBRUARY 7.15PM & 17 FEBRUARY 2PM “There’s a real buzz and sense of purpose about what this company is doing” ~ The Guardian www.niopera.com Grand Opera House, Belfast Welcome to The Grand Opera House for this new production of The Flying Dutchman. This is, by some way, NI Opera’s biggest production to date. Our very first opera (Menotti’s The Medium, coincidentally staged two years ago this month) utilised just five singers and a chamber band, and to go from this to a grand opera demanding 50 singers and a full symphony orchestra in such a short space of time indicates impressive progress. Similarly, our performances of Noye’s Fludde at the Beijing Music Festival in October, and our recent Irish Times Theatre Award nominations for The Turn of the Screw, demonstrate that our focus on bringing high quality, innovative opera to the widest possible audience continues to bear fruit. It feels appropriate for us to be staging our first Wagner opera in the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, but this production marks more than just a historical anniversary. Unsurprisingly, given the cost and complexities involved in performing Wagner, this will be the first fully staged Dutchman to be seen in Northern Ireland for generations. More unexpectedly, perhaps, this is the first ever new production of a Wagner opera by a Northern Irish company. Northern Ireland features heavily in this production. The opera begins and ends with ships and the sea, and it does not take too much imagination to link this back to Belfast’s industrial heritage and the recent Titanic commemorations. -

The Marriage of Figaro

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY Charles A. Sink, President Lester McCoy, Conductor Gail W. Rector, Executive Director First Concert 1957-1958 Complete Series 3216 Twelfth Annual Extra Concert Series THE NBC OPERA COMPANY m THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO MOZART SUNDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 6, 1957, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN THE CAST Count Almaviva WALTER CASSEL Countess Almaviva MARGUERITE WILLAUER Susanna, the Countess' maid JUDITH RASKIN Figaro, the Count's valet . MAC MORGAN Cherubino, the Count's page REGINA SARFATY Marcellina, an aged dame . RUTH KOBART Basilio, a music master LUIGI VELUCCI Don Curzio, a judge FRED CUSHMAN Bartolo, a doctor . EMILE RENAN Antonio, a gardener-Susanna's uncle EUGENE GREEN Barbarina, his daughter . BERTE GOAPERE Crier . RICHARD KRAUSE Country men and women, court attendants, hunters, and servants. (Cast subject to change) Conductor and Stage Director: PETER HERMAN ADLER Baldwin piano courtesy 0/ Maddy Music Company, Ann Arbor. A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO By WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Libretto by DAPONTE Based on a comedy by BEAUMARCHAIS English version: EDWARD EAGER Producer: SAMUEL CHOTZINOFF Music and Artistic Director: PETER HERMAN ADLER General Manager: CHANDLER COWLES Costumes: ALVIN COLT The action takes place in the castle and grounds of the Count and Countess Almaviva, near Seville. ACT I Count Almaviva, grown faithless to his Rosina after some years of marriage, has cast a roving eye upon her maid, Susanna, the bride-to-be of his valet, Figaro; while the Count's page, young Cherubino, has fallen in love, if you please, with the Countess herself. -

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations. by Heewon Uhm A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Halen, Chair Professor Anthony D. Elliott Professor Freda A. Herseth Professor Andrew W. Jennings Assisant Professor Youngju Ryu Heewon Uhm [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8334-7912 © Heewon Uhm 2019 DEDICATION To God For His endless love To my dearest teacher, David Halen For inviting me to the beautiful music world with full of inspiration To my parents and sister, Chang-Sub Uhm, Sunghee Chun, and Jungwon Uhm For trusting my musical journey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF EXAMPLES iv ABSTRACT v RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 9 Recital 2 Program 9 Recital 2 Program Notes 10 RECITAL 3 18 Recital 3 Program 18 Recital 3 Program Notes 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 iii LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE Ex-1 Semachi Rhythm 15 Ex-2 Gutgeori Rhythm 15 Ex-3 Honzanori-1, the transformed version of Semachi and Gutgeori rhythm 15 iv ABSTRACT In lieu of a written dissertation, three violin recitals were presented. Recital 1: Theme and Variations Monday, November 5, 2018, 8:00 PM, Stamps Auditorium, Walgreen Drama Center, University of Michigan. Assisted by Joonghun Cho, piano; Hsiu-Jung Hou, piano; Narae Joo, piano. Program: Olivier Messiaen, Thème et Variations; Johann Sebastian Bach, Ciaconna from Partita No. -

The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op

The Critical Reception of Beethoven’s Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op. 124 Translated and edited by Robin Wallace © 2020 by Robin Wallace All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-7348948-4-4 Center for Beethoven Research Boston University Contents Foreword 6 Op. 123. Missa Solemnis in D Major 123.1 I. P. S. 8 “Various.” Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 1 (21 January 1824): 34. 123.2 Friedrich August Kanne. 9 “Beethoven’s Most Recent Compositions.” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat 8 (12 May 1824): 120. 123.3 *—*. 11 “Musical Performance.” Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode 9 (15 May 1824): 506–7. 123.4 Ignaz Xaver Seyfried. 14 “State of Music and Musical Life in Vienna.” Caecilia 1 (June 1824): 200. 123.5 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of May.” 15 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 26 (1 July 1824): col. 437–42. 3 contents 123.6 “Glances at the Most Recent Appearances in Musical Literature.” 19 Caecilia 1 (October 1824): 372. 123.7 Gottfried Weber. 20 “Invitation to Subscribe.” Caecilia 2 (Intelligence Report no. 7) (April 1825): 43. 123.8 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of March.” 22 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 29 (25 April 1827): col. 284. 123.9 “ .” 23 Allgemeiner musikalischer Anzeiger 1 (May 1827): 372–74. 123.10 “Various. The Eleventh Lower Rhine Music Festival at Elberfeld.” 25 Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 156 (7 June 1827). 123.11 Rheinischer Merkur no. 46 27 (9 June 1827). 123.12 Georg Christian Grossheim and Joseph Fröhlich. 28 “Two Reviews.” Caecilia 9 (1828): 22–45. -

Hugh Lecaine Agnew Curriculum Vitae

HUGH LECAINE AGNEW CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION PhD, 1981, Stanford University AM, 1976, Stanford University BA (Honours, First Class), 1975, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT At The George Washington University: Professor of History and International Affairs, 2006-present Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, 1992-2006 Assistant Professor of History and International Affairs, 1988-1992 At the national university of Singapore Lecturer, Department of History, 1982-1988 At Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada Assistant Professor, Department of History, 1981-1982 Lecturer, Department of History, 1980-1981 1 2 PUBLICATIONS Books: The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2004). Czech translation, Češi a země Koruny české (Prague: Academia, 2008). Origins of the Czech National Renascence (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993). Edited volumes: Documentary Readings in European Civilization since 1715, (Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt Publishing, 2000). Issued in a second, corrected edition in 2006. Refereed Articles and Book Chapters: “Symbol and Ritual in Czech Politics in the Era of the “Tábory Lidu,” in Jiří Pokorný, Luboš Velek, and Alice Velková, eds., Nacionalismus, společnost a kultura ve střední Evropě 19. a 20. století – Nationalismus, Gesellschaft und Kultur in Mitteleuropa im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert: Pocta Jiřímu Kořalkovi k 75. narozeninám. Prague: Karolinum, 2007), pp. 393-408. “The Flyspecks on Palivec’s Portrait: Francis Joseph, the Symbols of Monarchy, and Czech Popular Loyalty,” in Laurence Cole and Daniel L. Unowsky, eds., The Limits of Loyalty: Imperial symbolism, popular allegiances, and state patriotism in the late Habsburg Monarchy (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2007), pp. -

The Time Is Now Thethe Timetime Isis Nownow Music Has the Power to Inspire, to Change Lives, to Illuminate Perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to Shift Our Vantage Point

20/21 SEASON The Time Is Now TheThe TimeTime IsIs NowNow Music has the power to inspire, to change lives, to illuminate perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to shift our vantage point. featuring FESTIVAL Your seats are waiting. Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression An exploration of humankind’s capacity for hope, courage, and resistance in the face of the unimaginable PERSPECTIVES Rhiannon Giddens “… an electrifying artist …” —Smithsonian PERSPECTIVES Yannick Nézet-Séguin “… the greatest generator of energy on the international podium …” —Financial Times PERSPECTIVES Jordi Savall “… a performer of genius but also a conductor, a scholar, a teacher, a concert impresario …” —The New Yorker DEBS COMPOSER’S CHAIR Andrew Norman “… the leading American composer of his generation ...” —Los Angeles Times Left: Youssou NDOUR On the cover: Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla carnegiehall.org/subscribe | 212-247-7800 Photos: NDOUR by Jack Vartoogian, Gražinytė-Tyla by Benjamin Ealovega. Box Office at 57th and Seventh Rafael Pulido Some of the most truly inspiring music CONTENTS you’ll hear this season—or any other season—at Carnegie Hall was written in response to oppressive forces that have 3 ORCHESTRAS ORCHESTRAS darkened the human experience throughout history. Perspectives: Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression takes audiences Yannick Nézet-Séguin on a journey unique among our festivals for the breadth of music 12 these courageous artists employed—from symphonies to jazz to Debs Composer’s popular songs and more. This music raises the question of why, 13 Chair: Andrew Norman no matter how horrific the circumstances, artists are nonetheless compelled to create art; and how, despite those circumstances, 28 Zankel Hall Center Stage the art they create can be so elevating.