The Intersection of Environment and Industry in Portland, Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination

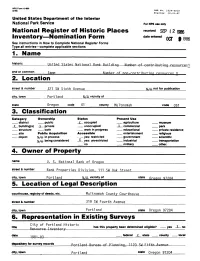

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received SEP I 2 1Q86 date entered Inventory—Nomination Form OCT §1986 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic United States National Rank RiiilHing of contributing resourcesj_ and or common Same Numhpr nf nnn-rnntrihntinn rp<;rmrrp<; D 2. Location street & number 321 SW Sixth Avenue not for publication city, town Portland vicinity of state Oregon code 41 county Multnomah code 051 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum _X_ building(s) X private unoccupied y commercial structure both work in progress educational __ private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object |\|//\ in process yes: restricted government scientific M/A being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation IT/ 7\ *^ "no __ military __ other: name U. S. National Rank nf Drpgnn street & number Bank Properties Division. 111 SI/J Oak St city, town Portland vicinity of state Qreaon Q7?f)4 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Multnomah County Courthouse street & number 319 SW Fourth Avenue city, town Portland state Oregon 97204 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title City of Portland Historic has this property been determined eligible? yes X no Resource Inventory———— federal _X_ state county __ local date 1981-83 depository for survey records Portland Bureau of Planning, 1120 SW Fifth Avpnnp city, town Portland state Oregon 97204 7. -

City Club of Portland Report: Portland Metropolitan Area Parks

Portland State University PDXScholar City Club of Portland Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 9-23-1994 City Club of Portland Report: Portland Metropolitan Area Parks City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.) Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.), "City Club of Portland Report: Portland Metropolitan Area Parks" (1994). City Club of Portland. 470. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub/470 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in City Club of Portland by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CITY CLUB OF PORTLAND REPORT Portland Metropolitan Area Parks Published in City Club of Portland Bulletin Vol. 76, No. 17 September 23,1994 CITY CLUB OF PORTLAND The City Club membership will vote on this report on Friday September 23, 1994. Until the membership vote, the City Club of Portland does not have an official position on this report. The outcome of this vote will be reported in the City Club Bulletin dated October 7,1994. (Vol. 76, No. 19) CITY CLUB OF PORTLAND BULLETIN 93 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 96 II. A VISION FOR PORTLAND AREA PARKS 98 A. Physical Aspects 98 B. Organizational Aspects 98 C. Programmatic Aspects 99 III. INTRODUCTION 99 IV. BACKGROUND 100 A. -

The Genesis of Portland's Forest Park : Evolution of an Urban Wilderness

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2009 The genesis of Portland's Forest Park : evolution of an urban wilderness Elizabeth M. Provost Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons, Land Use Law Commons, and the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Provost, Elizabeth M., "The genesis of Portland's Forest Park : evolution of an urban wilderness" (2009). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3990. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5874 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Elizabeth M. Provost for the Master of Arts in History were presented June 9, 2009, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: William Lang, Chair David Johns Carl Abbott DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: Thomas Luckett, Chair Department of History ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Elizabeth M. Provost for the Master of Arts in History presented June 9, 2009. Title: The Genesis of Portland's Forest Park: Evolution of an Urban Wilderness Portland, Oregon, is steward to a 5,126 acre wilderness park called Forest Park. The park's size and proximity to downtown make it a dominate feature of Portland's skyline. Despite its urban location the park provides respite from city life with its seventy miles of trails, which wind through stands of Douglas fir, western red cedar, and western hemlock. -

Built the First Rock Road in That County. Through All This Period He Was

COLUMBiA RIVER VALLEY 493 of Missouri; Robert, of Kansas; Dr. Francis Graffis, of Portland, Oregon; Mrs. Emma Reissner, a widow, who is a twin sister of D. B. Reasoner and who resides in Los Angeles, California; and Dr. Nettie Bawn, of Long Beach, California. D. B. Reasoner acquired his education in the frontier schools of Iowa and re- mained at home until his marriage in 1881.Two years later he came to the north- west, settling at Pomeroy, Washington, where he worked at the carpenter trade for about a year, having learned the trade some time previously.In 1884 he removed to Newberg, Oregon, where he engaged in contracting and building for about four years and then took up his abode in Middleton, Washington county, Oregon, where he became prominent in public life and was the first county commissioner elected to a four-year term.Through reelection he served eight years and later he was the first to be chosen county judge for a six years' term.While filling the office of county commissioner he bought the first rock crusher used in Washington county and also built the first rock road in that county.Through all this period he was likewise engaged in farming, meeting with very satisfactory success.He lived in Hillsboro until 1923, when he sold a part of his holdings in that county and established his home in Vernonia, where he took charge of the construction of a logging railroad. In 1924 he was appointed city clerk and recorder and is still serving in the dual capacity.In 1898 he was engaged in cutting piling on the Molalla river, rafting the piles to Oregon City, where he brailed them together and ran them through the locks to St.