Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

April-2014.Pdf

BEST I FACED: MARCO ANTONIO BARRERA P.20 THE BIBLE OF BOXING ® + FIRST MIGHTY LOSSES SOME BOXERS REBOUND FROM MARCOS THEIR INITIAL MAIDANA GAINS SETBACKS, SOME DON’T NEW RESPECT P.48 P.38 CANELO HALL OF VS. ANGULO FAME: JUNIOR MIDDLEWEIGHT RICHARD STEELE WAS MATCHUP HAS FAN APPEAL ONE OF THE BEST P.64 REFEREES OF HIS ERA P.68 JOSE SULAIMAN: 1931-2014 ARMY, NAV Y, THE LONGTIME AIR FORCE WBC PRESIDENT COLLEGIATE BOXING APRIL 2014 WAS CONTROVERSIAL IS ALIVE AND WELL IN THE BUT IMPACTFUL SERVICE ACADEMIES $8.95 P.60 P.80 44 CONTENTS | APRIL 2014 Adrien Broner FEATURES learned a lot in his loss to Marcos Maidana 38 DEFINING 64 ALVAREZ about how he’s FIGHT VS. ANGULO perceived. MARCOS MAIDANA THE JUNIOR REACHED NEW MIDDLEWEIGHT HEIGHTS BY MATCHUP HAS FAN BEATING ADRIEN APPEAL BRONER By Doug Fischer By Bart Barry 67 PACQUIAO 44 HAPPY FANS VS. BRADLEY II WHY WERE SO THERE ARE MANY MANY PEOPLE QUESTIONS GOING PLEASED ABOUT INTO THE REMATCH BRONER’S By Michael MISFORTUNE? Rosenthal By Tim Smith 68 HALL OF 48 MAKE OR FAME BREAK? REFEREE RICHARD SOME FIGHTERS STEELE EARNED BOUNCE BACK HIS INDUCTION FROM THEIR FIRST INTO THE IBHOF LOSSES, SOME By Ron Borges DON’T By Norm 74 IN TYSON’S Frauenheim WORDS MIKE TYSON’S 54 ACCIDENTAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTENDER IS FLAWED BUT CHRIS ARREOLA WORTH THE READ WILL FIGHT By Thomas Hauser FOR A TITLE IN SPITE OF HIS 80 AMERICA’S INCONSISTENCY TEAMS By Keith Idec INTERCOLLEGIATE BOXING STILL 60 JOSE THRIVES IN SULAIMAN: THE SERVICE 1931-2014 ACADEMIES THE By Bernard CONTROVERSIAL Fernandez WBC PRESIDENT LEFT HIS MARK ON 86 DOUGIE’S THE SPORT MAILBAG By Thomas Hauser NEW FEATURE: THE BEST OF DOUG FISCHER’S RINGTV.COM COLUMN COVER PHOTO BY HOGAN PHOTOS; BRONER: JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BOY/GETTY IMAGES BOY/GETTY JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BRONER: BY HOGAN PHOTOS; PHOTO COVER By Doug Fischer 4.14 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 30 5 RINGSIDE 6 OPENING SHOTS Light heavyweight 12 COME OUT WRITING contender Jean Pascal had a good night on 15 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES Jan. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04Rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA Won Title: 04-02-05 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13 -03 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: 04-30 -05 _________________________________ Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 04-30 -05 World C hampion: VACANT Last Defense: 02-26- 05 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: JEAN MARC MORMECK- IBF: O’NEIL BELL WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBO : JOHNNY NELSON WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI 1. NICOLAY VALUEV (OC) RUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. JORGE CASTRO (LAC) ARG 2. NOT RATED 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. GUILLERMO JONES (0C) PAN 3. MANNY SIACA (LAC-INTERIM) P.R. ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. RAY AUSTIN (LAC) USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( 5. CALVIN BROCK USA 5. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA l 6. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of FEBRUARY 2005 Created on March 20Th, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF FEBRUARY 2005 Created on March 20th, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA World Champion: World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13-03 Won Title: 03-20- 04 JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA Last Mandator y: Won Title: 02-23- 02 Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 11-13-04 Last Mandatory: 05-22 -04 Last Defense: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 05-22-04 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: VACANT - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBC: WAYNE BRAITWAITE - IBF: VACANT WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI WBO : JOHNNY NELSON 1. HASIM RAHMAN USA 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. MEDHI SAHNOUNE FRA 2. JAMES TONEY USA 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. THOMAS ULRICH (EBU) GER 3. LANCE WHITAKER USA 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. O’NEILL BELL (NABF) USA 3. SILVIO BRANCO (WBA INTERCONT.) ITA ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. MONTE BARRETT USA 4. GUILLERMO JONES (LAC) PAN (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GEORGE KHALID JONES (NABA) USA ( 5. NICOLAY VALUEV (WBA INTERC.) RUS 5. VINCENZO CANTATORE ITA 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA 6. -

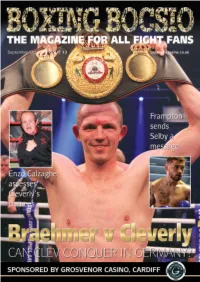

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

Dark Trade: Lost in Boxing Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DARK TRADE: LOST IN BOXING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Donald McRae | 624 pages | 05 Jun 2014 | Simon & Schuster Ltd | 9781471135378 | English | London, United Kingdom Dark Trade: Lost in Boxing PDF Book Posted on October 30, Updated on October 31, The impact of that experience has shaped much of his non-fiction writing. Start your review of Dark Trade: Lost in Boxing. Dark Trade: Lost in Boxing. Trivia About Dark Trade: Lost His books have been praised consistently for their intimacy of tone and breadth of research as he draws the reader deep inside the heads of his extraordinary subjects. The reader will feel like he or she knows the person portrayed more intimately than before turning the pages. Not a Member? The way McRae relates back to stories of him and his wife shows the reader that although he is constantly with stardom of the sport, he still watches as a fan. The personal connections between fighter and writer are special; McRae taps into something most boxing journalists or writers since this book was first released simply A wonderfully-written time capsule of the boxing landscape, with McRae going in deep with heavy hitters such as Mike Tyson, James Toney, Chris Eubank, and Naseem Hamed. Paperback , pages. Pages: Sales rank: , Product dimensions: 6. What he shares with them most, he comes to realize, is that he is hopelessly, and willingly, lost in boxing. The personal connections between fighter and writer are special; McRae taps into something most boxing journalists or writers since this book was first released simply are incapable of reaching. -

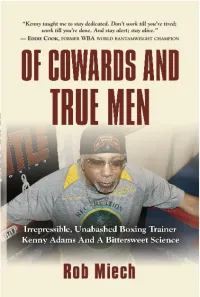

Of Cowards and True Men Order the Complete Book From

Kenny Adams survived on profanity and pugilism, turning Fort Hood into the premier military boxing outfit and coaching the controversial 1988 U.S. Olympic boxing team in South Korea. Twenty-six of his pros have won world-title belts. His amateur and professional successes are nonpareil. Here is the unapologetic and unflinching life of an American fable, and the crude, raw, and vulgar world in which he has flourished. Of Cowards and True Men Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/8941.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Enjoy your free excerpt below! Of Cowards and True Men Rob Miech Copyright © 2015 Rob Miech ISBN: 978-1-63490-907-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2015 First Edition I URINE SPRAYS ALL over the black canvas. A fully loaded Italian Galesi-Brescia 6.35 pearl-handled .25-caliber pistol tumbles onto the floor of the boxing ring. Just another day in the office for Kenny Adams. Enter the accomplished trainer’s domain and expect anything. “With Kenny, you never know,” says a longtime colleague who was there the day of Kenny’s twin chagrins. First off, there’s the favorite word. Four perfectly balanced syllables, the sweet matronly beginning hammered by the sour, vulgar punctuation. -

Undefeated Tavoris Cloud Defends Ibf Light Heavyweight Title Against Jean Pascal on Saturday, Aug

UNDEFEATED TAVORIS CLOUD DEFENDS IBF LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT TITLE AGAINST JEAN PASCAL ON SATURDAY, AUG. 11, LIVE ON SHOWTIME® NEW YORK (May 29, 2012) – A light heavyweight world championship showdown—potentially the division’s best matchup in years between two young fighters in their prime—has been confirmed for Saturday, Aug. 11, at Bell Centre in Montreal, Canada, when undefeated International Boxing Federation (IBF) light heavyweight champion Tavoris Cloud (24-0, 19 KOs), of Tallahassee, Fla., defends his title against popular hometown favorite and former World Boxing Council (WBC) light heavyweight titleholder Jean Pascal (26-2-1, 16 KOs) on SHOWTIME CHAMPIONSHIP BOXING live on SHOWTIME®. The co-feature will match budding Canadian knockout artist Adonis “Superman” Stevenson, (18-1, 15 KOs) of Montreal (Canada), against an opponent to be announced in a super middleweight bout. Cloud is known as a no-nonsense power puncher, who comes right at his opponents with few frills. Pascal may not equal Cloud in work rate, but his footwork and explosive combinations make for a compelling matchup between ferocious punchers. Both men will be coming in to not only win, but to make a statement as the best puncher in one of boxing’s glamor divisions. The 5-foot-10, 30-year-old Cloud will be making the fifth defense of the then-vacant 175-pound title he won via 12-round unanimous decision over Clinton Woods on Aug. 28, 2009. The hard-hitting, 29-year-old successfully defended against Glen Johnson (unanimous decision, June 7, 2010), Fulgencio Zuniga (unanimous decision, Dec. 17, 2010) and Yusaf Mack (TKO 8, June 28, 2011) before winning a controversial split decision over Gabriel Campillo in February. -

«Lo Scandalo Las Vegas» Napoli in Esilio

SPORT Hagler sei mesi dopo il match mondiale con Léonard Basket d'Italia, Milano in Usa «Lo scandalo Las Vegas» Napoli in esilio ossessiva ntoma il match con Léonard che gli PIEHFHANCESCO PANtMU.0 L'ex campione a Livorno commentatore tv «hanno rubato». «Credo comunque che Léo nard si sia davvero ritirato. Lo ha latto un mese M 11 «nonsense» non sem rigrotta, già noto alle crona dopo proprio per non incontrarmi più». E visto pre fa ridere. Ma il paradosso che per essere occupato da «Ho subito un furto, sono io il numero 1» che sua maestà insiste tanto su quel famoso e che il basket italiano sta viven tutti tranne che dal basket, discusso match del 4 aprile, è d'obbligo chie do in questo momento rag viene requisito per «motivi re «Stanno ancora indagando su un giudice» dergli un'opinione circa te voci e i sospetti che giunge punte di ridicolo Inim ferendari». Il palazzetto serve lo hanno alimentato. «Sì è vero, c'è stata un'in maginabili, anche se circo da deposito per schede, urne, tavoli per la prossima consul chiesta dello Stato del Nevada su di un giudice. scritte alla piazza napoletana. «Se ritomo, sarò di nuovo grande» Nel momento del «grandi tazione popolare dell'8 no So che stanno ancora indagando. Di sicuro vembre. Risultato: altre tre DAL NOSTRO INVIATO posso dire che c'è stato un contatto tra un orizzonti cestistlci» sbandiera ti dalla Lega, e dall'ingresso settimane di esodo e prima MARCO MAZZANTI giudice e un pugile alla vigilia dell'incontro». -

I-CON Was a Blast

--- 4 - - VOLUME 33, NUMBER 48 STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT STONY BROOK THURSDAY, APRIL 5, 1990 M- Budget Rally Is J990-91 Budget A Real Washout'. Gets Approved By ohn atao A rally to protest a proposed tuition hike, By Mary Dunop parking fees and cuts in the SUNY budget, as lne Polity Senate meeting approved the well as to call attention to the need for the 199;s91 budget last Wednesday night. state to fully fund the university, fell thugh Racieal Boatswain, Polity Treasurer, yesterday despite a promising press confer- explained how the $1,300,000 budget is ence earlier in the day. dispersed to the programs, clubs, college Glenn Magpantay, SASU delegate for legislatures, and referendums. Stony Brook, moderated the press confer- "We expect 9,200 students to pay the ence, attended by student and professional activity fee," said Boatswain. The activity fee nedia. Although student attendance was for next year is $129, and is the revenue for low at the event, the speakers were not the budget discouraged. All of the referendums that were voted on In his opening comments, Magpantay in the recent elections passed. *'he referen- said, "One of the reasons why we are here dums are final. We cannot touch that today at this press conference is to inform money, it is what the general population the press, the students, the faculty, the staff voted on," said Dan Slepian, Polity Vice of this university about what's going on with President. SUNY, what's going on with our university, The senate approved to reduce the col- what we as students, faculty, staff and Marina Sirtis ousxmonf -nuw lege legislatures by $100 each, and Commu- members of SUNY at Stony Brook are going ter College by $200. -

«Ora Mi Scoprirete, Parola Di Kalambay»

SPORT In dodici formidabili «Mi sono preso una bella Maurilio De Zolt vince il titolo riprese il pugile italiano rivincita con chi nazionale ha annullato Me Callum guarda solo ai campioni nella 50 km confermandosi re dei medi stranieri e mi snobbava» Dopo l'argento conquistato alle Olimpiadi Invernali di Calgary II trentottenne vigile del fuoco Maurilio De Zolt ha Ieri dato un'altra prova della sua classe. Sulla pista di Vezzena 11 «Grillo» ha vinto II titolo italiano nella SO chilometri. Al secondo posto è arrivato Silvano Buco (Fiamme Gialle), vincitore del titolo tricolore della 30 chilometri in gennaio. Terzo Alfred Runggaldier (Cara binieri). Barco ha avuto un vantaggio di 16' su De Zolt fino al 2S« chilometro: da questo punto in poi, complice «Ora mi scoprirete, anche una caduta del finanziere, è Iniziata la rimonta. •Grillo» ha raggiunto al 37» chilometro Barco e l'ha staccato di quella manciata di secondi che gli è bastata per vincere. «Non me l'aspettavo - ha detto - dopo tutti I festeggiamenti che mi hanno fatto Due fratelli svedesi, Oer- parola di Kalambay» Una fase dell'aspro combattimento di Pesaro tra McCallum e Kalambay Sci da fondo: jan e Anders Blomqvist la Vasallopet sono arrivati insieme do- a due fratelli > I 90 chilometri della Patrizio Kalambay il giorno dopo. Dopo una vitto gran fondo. Cosi la giuria svedesi Il ha proclamati vincitori a ria splendida contro Me Callum, conquistata in 12 par! merito della sessanta- riprese di tattica squisita e entusiasmante combat Un campione alla Mitri ^^"^^mmmmm^^ cinqueslma edizione della tività. Le dichiarazioni del pugile sono improntate Vasallopet, la più prestigiosa competizione di sci da alla felicità: «Adesso anche quelli che si riempiono fondo che si disputa con lo stile classico sul 90 chilo GIUSEPPE SIGNORI metri che separano le cittì svedesi di Saelen e Mora e la bocca di nomi stranieri, scopriranno che da noi che è valevole per la Worldloppel, coppa del mondo esistono grandi pugili.