GUIDE for BEGINNING FOSSIL HUNTERS Charles Collinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois Fossils Doc 2005

State of Illinois Illinois Department of Natural Resources Illinois Fossils Illinois Department of Natural Resources he Illinois Fossils activity book from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ (IDNR) Division of Education is designed to supplement your curriculum in a vari- ety of ways. The information and activities contained in this publication are targeted toT grades four through eight. The Illinois Fossils resources trunk and lessons can help you T teach about fossils, too. You will find these and other supplemental items through the Web page at https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/education/Pages/default.aspx. Contact the IDNR Division of Education at 217-524-4126 or [email protected] for more information. Collinson, Charles. 2002. Guide for beginning fossil hunters. Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois. Geoscience Education Series 15. 49 pp. Frankie, Wayne. 2004. Guide to rocks and minerals of Illinois. Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois. Geoscience Education Series 16. 71 pp. Killey, Myrna M. 1998. Illinois’ ice age legacy. Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois. Geoscience Education Series 14. 67 pp. Much of the material in this book is adapted from the Illinois State Geological Survey’s (ISGS) Guide for Beginning Fossil Hunters. Special thanks are given to Charles Collinson, former ISGS geologist, for the use of his fossil illustrations. Equal opportunity to participate in programs of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and those funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies is available to all individuals regardless of race, sex, national origin, disability, age, reli-gion or other non-merit factors. -

Fossil Collecting Areas in Iowa

FOSSIL COLLECTING AREAS IN IOWA The following list, although far from compete, includes a few of the better fossil collecting areas in Iowa. 1. Rockford, Floyd County (¼ mile south and ¼ mile west of the Rockford Brick and Tile Company pit, on county road “D”). Well preserved brachiopods, gastropods, and corals are most abundant in the yellowish shales that overlie the blue-gray beds. The fossils occurring here are known as the Hackberry fauna and have been described by C.L. and M.A. Fenton in a book entitled, “The Hackberry State of the Upper Devonian,” published by the MacMillan Company in 1924. 2. Bird Hill, Cerro Gordo County This is near the center of the north line of section 24, T 95N, R.19W, about 3½ miles west and ¼ mile south of the Rockford Brick and Tile Company Plant. The Hackberry fauna can be collected here also. 3. Elgin-Clermont area, Fayette County In the Elgin Member of the Maquoketa Formation large trilobites and both straight and coiled cephalopods are found. Fragments of trilobites are common, but whole specimens are rare. Road cuts along the new highway between Clermont and Elgin, the dry stream bed along county road “Y” east of Clermont, and the high-road cuts along the Turkey River southeast of Elgin are all good collecting sites. References for this area are: (1) Slocum, A.W., “Trilobites from the Maquoketa Beds of Fayette County, Iowa,” Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, Volume 25; (2) Walter, O.T., “Trilobites of Iowa and some Related Paleozoic Forms,” Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, Volume 31; (3) Ladd, H.S., “Stratigraphy and Paleontology of the Maquoketa Shale of Iowa,” Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, Volume 34. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

The Paleontology Synthesis Project and Establishing a Framework for Managing National Park Service Paleontological Resource Archives and Data

Lucas, S.G. and Sullivan, R.M., eds., 2018, Fossil Record 6. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 79. 589 THE PALEONTOLOGY SYNTHESIS PROJECT AND ESTABLISHING A FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGING NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCE ARCHIVES AND DATA VINCENT L. SANTUCCI1, JUSTIN S. TWEET2 and TIMOTHY B. CONNORS3 1National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 1849 “C” Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20240, [email protected]; 2National Park Service, 9149 79th Street S., Cottage Grove, MN 55016, [email protected]; 3National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 12795 W. Alameda Parkway, Lakewood, CO 80225, [email protected] Abstract—The National Park Service Paleontology Program maintains an extensive collection of digital and hard copy documents, publications, photographs and other archives associated with the paleontological resources documented in 268 parks. The organization and preservation of the NPS paleontology archives has been the focus of intensive data management activities by a small and dedicated team of NPS staff. The data preservation strategy complemented the NPS servicewide inventories for paleontological resources. The first phase of the data management, referred to as the NPS Paleontology Synthesis Project, compiled servicewide paleontological resource data pertaining to geologic time, taxonomy, museum repositories, holotype fossil specimens, and numerous other topics. In 2015, the second phase of data management was implemented with the creation and organization of a multi-faceted digital data system known as the NPS Paleontology Archives and NPS Paleontology Library. Two components of the NPS Paleontology Archives were designed for the preservation of both park specific and servicewide paleontological resource archives and data. A third component, the NPS Paleontology Library, is a repository for electronic copies of geology and paleontology publications, reports, and other media. -

Homeomorphic Gastropods from the Silurian of Norway, Estonia and Bohemia

Homeomorphic gastropods from the Silurian of Norway, Estonia and Bohemia MARE ISAKAR, JAN OVE R. EBBESTAD & JOHN S. PEEL Isakar, M,. Ebbestad, J. O. R. & Peel, J. S.: Homeomorphic gastropods from the Silurian of Norway, Estonia and Bohemia. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 79, pp. 281-288. Oslo 1999. ISSN 0029-196X. Redescription of the gastropodEuomphalus undiferus Schmidt, 1858 fromthe Upper Llandovery Rumba Formation of Estonia requires reinvestigation of the hitherto monotypic genus Kiaeromphalus Peel & Y ochelson, 1976, originally described from the Rytteråker Formation of the Oslo Region. The Estonian K. undiferus and the Norwegian type species occur in similar depositional facies of Early Silurian age within the sedgwickii Graptolite Zone. The redescribed type specimen of Horologium kokeni Perner, 1907 from the late Silurian (Ludlow) of Bohemia shows strong morphological convergence with the two Baltic species, but Kiaeromphalus is distinguished by its lower rate of whorl expansion and less oblique aperture. Both genera were adapted to a sessile life, possibly on a soft substratum. Mare lsakar, Museum ofGeology, University ofTartu, Vanemuise 46, 51014 Tartu, Estonia. E-mail: [email protected]; Jan OveR. Ebbestad & JohnS. Peel, Department of Earth Sciences (Historical Geology and Palaeontology), Uppsala University, Norbyviigen 22, S-752 36 Uppsala, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Introduction morphic, genera; Schmidt's (1858) species from Estonia is ascribed to the latter genus. Thus, Kiaeromphalus occurs In 1976, Peel & Yochelson reviewed Early Silurian from southem Norway to Estonia in the Lower Silurian (Llandovery) gastropods from the Oslo Region and rocks, although it remains unreported from the Silurian of proposed two new genera, Kiaeromphalus and Kjerulfo Sweden. -

Fossil Collecting in Ohio

No. 17 OHIOGeoFacts DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES • DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FOSSIL COLLECTING IN OHIO Hobbyists have long known about Ohio’s great abundance and WHERE FOSSILS ARE FOUND IN OHIO diversity of fossils. Many world-famous paleontologists—geologists who study fossils—began their careers as youngsters collecting fossils Ordovician rocks in Ohio are world famous for in their native Ohio. Fossils from Ohio are important constituents the abundance, variety, and excellent preserva- of museum collections throughout the United States and Europe. tion of the fossils they contain. The limestones and shales exposed in almost every road cut or WHY OHIO HAS FOSSILS stream bed in southwestern Ohio, southeastern Indiana, and north-central Kentucky provide The area that is now Ohio was not always dry land as it is today. the opportunity to collect a bonanza of fossils. Approximately 510 million years ago (m.y.a.), Ohio was south of the Among the more abundant types of fossils col- Equator. As the North American Plate moved to its current position ORDOVICIAN lected from Ordovician rocks are brachiopods, 508–438 m.y.a. through the process of plate tectonics, tropical to subtropical seas bryozoans, gastropods, and trilobites. repeatedly transgressed over the plate. It is because of those warm Silurian rocks of western Ohio are not known seas that Ohio has the abundant fossils that people collect today. for their fossils. When the limestones and shales The seas that covered Ohio during the Ordovician, Silurian, and were fi rst deposited they were quite fossilifer- most of the Devonian Periods of the Paleozoic Era were the site of ous. -

The Greatest Challenge to 21St Century Paleontology: When Commercialization of Fossils Threatens the Science

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org The greatest challenge to 21st century paleontology: When commercialization of fossils threatens the science Kenshu Shimada, Philip J. Currie, Eric Scott, and Stuart S. Sumida As we proceed into the 21st century, the sci- responses to geological and climatic factors. Pale- ence of paleontology has achieved a remarkable ontology presently enjoys a new “Golden Age,” prominence and popularity, providing increasingly progressing by leaps while also serving, as always, detailed perspective on critical biological and geo- to inspire young minds to explore science and the logical processes. Spectacular new discoveries natural world. excite the imagination and spur new investigations, Yet at the outset of the millennium, three inter- while more abundant fossils studied using new connected, troubling challenges confront paleontol- techniques enable more precise interpretations of ogists: 1) a shrinking job market, 2) diminishing diversity, variation, changes through time, and funding sources, and 3) heightened commercial- Editor’s note: The commercial collection and sale of fossils, as well as the still developing regulations involving collection of fossils on public lands, have emerged as one of the most contentious issues in pale- ontology. These issues pit not only professional paleontologists and commercial collectors against each other, but have produced rifts within the paleontological community. Here Shimada and his co-authors vig- orously present a position supported by many vertebrate paleontologists. I repeat a call in an earlier com- mentary (Plotnick, 2011; palaeo-electronica.org/2011_1/commentary/mainstream.htm) for additional contributions that would discuss these issues that are so crucial to our field. Please send directly to Roy E. -

Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology EDUCATOR's GUIDE

Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology EDUCATOR’S GUIDE Dear Educator: This guide is recommended for educators of grades K-4 and is designed to help you prepare students for their Alf Museum visit, as well as to provide resources to enhance your classroom curriculum. This packet includes background information about the Alf Museum and the science of paleontology, a summary of our museum guidelines and what to expect, a pre-visit checklist, a series of content standard-aligned activities/exercises for classroom use before and/or after your visit, and a list of relevant terms and additional resources. Please complete and return the enclosed evaluation form to help us improve this guide to better serve your needs. Thank you! Paleontology: The Study of Ancient Life Paleontology is the study of ancient life. The history of past life on Earth is interpreted by scientists through the examination of fossils, the preserved remains of organisms which lived in the geologic past (more than 10,000 years ago). There are two main types of fossils: body fossils, the preserved remains of actual organisms (e.g. shells/hard parts, teeth, bones, leaves, etc.) and trace fossils, the preserved evidence of activity by organisms (e.g. footprints, burrows, fossil dung). Chances for fossil preservation are enhanced by (1) the presence of hard parts (since soft parts generally rot or are eaten, preventing preservation) and (2) rapid burial (preventing disturbance by bio- logical or physical actions). Many body fossils are skeletal remains (e.g. bones, teeth, shells, exoskel- etons). Most form when an animal or plant dies and then is buried by sediment (e.g. -

Vertebrate Paleontology of the Cretaceous/Tertiary Transition of Big Bend National Park, Texas (Lancian, Puercan, Mammalia, Dinosauria, Paleomagnetism)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1986 Vertebrate Paleontology of the Cretaceous/Tertiary Transition of Big Bend National Park, Texas (Lancian, Puercan, Mammalia, Dinosauria, Paleomagnetism). Barbara R. Standhardt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Standhardt, Barbara R., "Vertebrate Paleontology of the Cretaceous/Tertiary Transition of Big Bend National Park, Texas (Lancian, Puercan, Mammalia, Dinosauria, Paleomagnetism)." (1986). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4209. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4209 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. -

Cretaceous Fossils from the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal

Cretaceous S;cial Publication No. 18 Fossils from the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal A Guide for Students and Collectors Edward M. Lauginiger / /~ / CRETACEOUS FOSSILS FROM THE CHESAPEAKE AND DELAWARE CANAL: A GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AND COLLECTORS By Edward M. Lauginiger Biology Teacher Academy Park High School Sharon Hill, Pennsylvania September 1988 Reprinted 1997 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION. • 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 PREVIOUS STUDIES. 3 FOSSILS AND FOSSILIZATION 5 Requirements for Fossilization 6 Types of Fossilization 7 GEOLOGY •• 10 CLASSIFICATON OF FOSSILS. 12 Kingdom Monera • 13 Kindgom Protista 1 3 Kingdom Plantae. 1 4 Kingdom Animalia 15 Phylum Porifera 15 Phylum Cnidaria (Coelenterata). 16 Phylum Bryozoa. 16 Phylum Brachiopoda. 17 Phylum Mollusca • 18 Phylum Annelida •. 22 Phylum Arthropoda • 23 Phylum Echinodermata. 24 Phylum Chordata 24 COLLECTING LOCALITIES 28 FOSSIL CHECK LIST 30 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 33 PLATES. ••• 39 iii FIGURES Page Figure 1 • Index map of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal Area. .. .. 2 Figure 2. Generalized stratigraphic column of the formations exposed at the C & D Canal. 11 Figure 3. Foraminifera 14 Figure 4. Porifera 16 Figure 5. Cnidaria 16 Figure 6. Bryozoa. 17 Figure 7. Brachiopoda. 18 Figure 8. Mollusca-Gastropoda. 19 Figure 9. Mollusca-Pelecypoda. 21 Figure 10. Mollusca-Cephalopoda 22 Figure 11. Annelida . 22 Figure 12. Arthropoda 23 Figure 13. Echinodermata. 25 Figure 1 4. Chordata . 27 Figure 1 5. Collecting localities at the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal . ... .. 29 v CRETACEOUS FOSSILS FROM THE CHESAPEAKE AND DELAWARE CANAL: A GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AND COLLECTORS Edward M. Lauginiger INTRODUCTION Fossil collectors have been attracted to Delaware since the late 1820s when the excavation of the Chesapeake and Delaware (C&D) Canal first exposed marine fossils of Cretaceous age (Fig. -

Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness

The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon Volume 84 Issue 1 Article 8 1-6-2012 Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/compass Part of the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2012) "Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness," The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon: Vol. 84: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/compass/vol84/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Figure. 1. Portrait of Mary Anning, in oils, probably painted by William Gray in February, 1842, for exhibition at the Royal Academy, but rejected. The portrait includes the fossil cliffs of Lyme Bay in the background. Mary is pointing at an ammonite, with her companion Tray dutifully curled beside the ammonite protecting the find. The portrait eventually became the property of Joseph, Mary‟s brother, and in 1935, was presented to the Geology Department, British Museum, by Mary‟s great-great niece Annette Anning (1876-1938). The portrait is now in the Earth Sciences Library, British Museum of Natural History. A similar portrait in pastels by B.J.M. Donne, hangs in the entry hall of the Geological Society of London. -

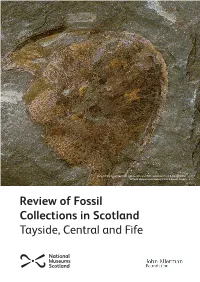

Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife

Detail of the Lower Devonian jawless, armoured fish Cephalaspis from Balruddery Den. © Perth Museum & Art Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Perth Museum and Art Gallery (Culture Perth and Kinross) The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum (Leisure and Culture Dundee) Broughty Castle (Leisure and Culture Dundee) D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum and University Herbarium (University of Dundee Museum Collections) Montrose Museum (Angus Alive) Museums of the University of St Andrews Fife Collections Centre (Fife Cultural Trust) St Andrews Museum (Fife Cultural Trust) Kirkcaldy Galleries (Fife Cultural Trust) Falkirk Collections Centre (Falkirk Community Trust) 1 Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Collection type: Independent Accreditation: 2016 Dumbarton Road, Stirling, FK8 2KR Contact: [email protected] Location of collections The Smith Art Gallery and Museum, formerly known as the Smith Institute, was established at the bequest of artist Thomas Stuart Smith (1815-1869) on land supplied by the Burgh of Stirling. The Institute opened in 1874. Fossils are housed onsite in one of several storerooms. Size of collections 700 fossils. Onsite records The CMS has recently been updated to Adlib (Axiel Collection); all fossils have a basic entry with additional details on MDA cards. Collection highlights 1. Fossils linked to Robert Kidston (1852-1924). 2. Silurian graptolite fossils linked to Professor Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899). 3. Dura Den fossils linked to Reverend John Anderson (1796-1864). Published information Traquair, R.H. (1900). XXXII.—Report on Fossil Fishes collected by the Geological Survey of Scotland in the Silurian Rocks of the South of Scotland.