TRANS-GILCHRIST-Ellen-Memories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BTC Catalog 172.Pdf

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 172 ~ First Books & Before 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2011 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com After 171 catalogs, we’ve finally gotten around to a staple of the same). This is not one of them, nor does it pretend to be. bookselling industry, the “First Books” catalog. But we decided to give Rather, it is an assemblage of current inventory with an eye toward it a new twist... examining the question, “Where does an author’s career begin?” In the The collecting sub-genre of authors’ first books, a time-honored following pages we have tried to juxtapose first books with more obscure tradition, is complicated by taxonomic problems – what constitutes an (and usually very inexpensive), pre-first book material. -

Best Lists of Iicontemporary" Fiction

BEST LISTS OF IICONTEMPORARY" FICTION In 1~83 the distinguished British novelist and provocateur, Al1thonyBurgcss, decided to issue a list of thp 99 Best Novels in English since WW H. Prc-sumablytht, hundredth slot was available for his readers to add one of his own. IA· :,i1e thisis all merely parlor games on a slightly higher level than "Trivial Ptlrsuit" or "Jcop~rdy", such '~oing~-on do providp somp provocative rcading lists for English Majors and/or people who love to read fiction. So herc arc BurgL'Ss' choices followed by the choices of the CSUS profossors teaching contemporary fiction on a regular basis since thpy were hired. ANTHONY BURGESS· 1939: Party Going by Henry Green. After Many a Summer Dies the Swan by Aldous Huxley. Finnegan's Wake by James Joyce. At Swim-Two-Birds byFlann O'Brien. 1940: The Power & The Glory byGraham Greene.'For Whcml The Bell Tollsby Ernest Hemingway. STRANGERS & BROTHERS(a series of novels to 1970) bye. P. Snow. 1941: The Aerodrome by Rex Wainer. 1944: The Horse's Mouth by Joyce Cary. The Razor's Edge by W. Somerset Maugham 1945.: Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh 1946: Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake 1947: The Victim by Saul Bellow. Under the \Iolcanoby MalcolmLowry 1948: The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene. The Naked and the Dead by . Norman Mailer. No Highway by Nevil Shute . 1949:The Heat ofthe Day by Elizabeth Bowen, Ape and Essence by Aldous Huxley, 1984 by George OrwelL The Body by William Sansom' 1950: Scenes From Provincial q{e by William Cooper. -

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene Knjige, Ki

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene knjige, ki jih imamo v naši knjižnični zbirki, so označene debelejše: Roman/kratke zgodbe 2018 Sigrid Nunez: The Friend 2017 Jesmyn Ward: Sing, Unburied, Sing 2016 Colson Whitehead THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD 2015 Adam Johnson FORTUNE SMILES: STORIES 2014 Phil Klay REDEPLOYMENT 2013 James McBrid THE GOOD LORD BIRD 2012 Louise Erdrich THE ROUND HOUSE 2011 Jesmyn Ward SALVAGE THE BONES 2010 Jaimy Gordon LORD OF MISRULE 2009 Colum McCann LET THE GREAT WORLD SPIN (Naj se širni svet vrti, 2010) 2008 Peter Matthiessen SHADOW COUNTRY 2007 Denis Johnson TREE OF SMOKE 2006 Richard Powers THE ECHO MAKER 2005 William T. Vollmann EUROPE CENTRAL 2004 Lily Tuck THE NEWS FROM PARAGUAY 2003 Shirley Hazzard THE GREAT FIRE 2002 Julia Glass THREE JUNES 2001 Jonathan Franzen THE CORRECTIONS (Popravki, 2005) 2000 Susan Sontag IN AMERICA 1999 Ha Jin WAITING (Čakanje, 2008) 1998 Alice McDermott CHARMING BILLY 1997 Charles Frazier COLD MOUNTAIN 1996 Andrea Barrett SHIP FEVER AND OTHER STORIES 1995 Philip Roth SABBATH'S THEATER 1994 William Gaddis A FROLIC OF HIS OWN 1993 E. Annie Proulx THE SHIPPING NEWS (Ladijske novice, 2009; prev. Katarina Mahnič) 1992 Cormac McCarthy ALL THE PRETTY HORSES 1991 Norman Rush MATING 1990 Charles Johnson MIDDLE PASSAGE 1989 John Casey SPARTINA 1988 Pete Dexter PARIS TROUT 1987 Larry Heinemann PACO'S STORY 1986 Edgar Lawrence Doctorow WORLD'S FAIR 1985 Don DeLillo WHITE NOISE (Beli šum, 2003) 1984 Ellen Gilchrist VICTORY OVER JAPAN: A BOOK OF STORIES 1983 Alice Walker THE COLOR PURPLE -

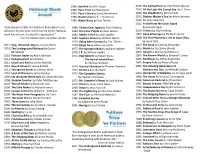

Fiction Award Winners 2019

1989: Spartina by John Casey 2016: The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen National Book 1988: Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 2015: All the Light We Cannot See by A. Doerr 1987: Paco’s Story by Larry Heinemann 2014: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt Award 1986: World’s Fair by E. L. Doctorow 2013: Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2012: No prize awarded 2011: A Visit from the Goon Squad “Established in 1950, the National Book Award is an 1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist by Jennifer Egan American literary prize administered by the National 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization.” 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout - from the National Book Foundation website. 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien by Junot Diaz 2018: The Friend by Sigrid Nunez 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2017: Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 2016: The Underground Railroad by Colson 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson Whitehead 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2004: The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson The Hair of Harold Roux 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay by Thomas Williams 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich 1973: Chimera by John Barth Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1972: The Complete Stories 2000: Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon by Flannery O’Connor 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 2009: Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann 1971: Mr. -

Fiction Winners

1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson National Book Award 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2004: The Known World 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike by Edward P. Jones 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich Kavalier and Clay 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis by Michael Chabon 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2000: Interpreter of Maladies 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2009: Let the Great World Spin The Hair of Harold Roux by Jhumpa Lahiri by Colum McCann by Thomas Williams 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 1998: American Pastoral by Philip Roth 2008: Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen 1973: Chimera by John Barth 1997: Martin Dressler: The Tale of an 1972: The Complete Stories 2007: Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson American Dreamer 2006: The Echo Maker by Richard Powers by Flannery O’Connor by Steven Millhauser 1971: Mr. Sammler’s Planet by Saul Bellow 1996: Independence Day by Richard Ford 2005: Europe Central by William T. Volmann 1970: Them by Joyce Carol Oates 1995: The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 2004: The News from Paraguay 1969: Steps -

Visitor Experience Chris Abani Edward Abbey Abigail Adams Henry Adams John Adams Léonie Adams Jane Addams Renata Adler James Agee Conrad Aiken

VISITOR EXPERIENCE CHRIS ABANI EDWARD ABBEY ABIGAIL ADAMS HENRY ADAMS JOHN ADAMS LÉONIE ADAMS JANE ADDAMS RENATA ADLER JAMES AGEE CONRAD AIKEN DANIEL ALARCÓN EDWARD ALBEE LOUISA MAY ALCOTT SHERMAN ALEXIE HORATIO ALGER JR. NELSON ALGREN ISABEL ALLENDE DOROTHY ALLISON JULIA ALVAREZ A.R. AMMONS RUDOLFO ANAYA SHERWOOD ANDERSON MAYA ANGELOU JOHN ASHBERY ISAAC ASIMOV JOHN JAMES AUDUBON JOSEPH AUSLANDER PAUL AUSTER MARY AUSTIN JAMES BALDWIN TONI CADE BAMBARA AMIRI BARAKA ANDREA BARRETT JOHN BARTH DONALD BARTHELME WILLIAM BARTRAM KATHARINE LEE BATES L. FRANK BAUM ANN BEATTIE HARRIET BEECHER STOWE SAUL BELLOW AMBROSE BIERCE ELIZABETH BISHOP HAROLD BLOOM JUDY BLUME LOUISE BOGAN JANE BOWLES PAUL BOWLES T. C. BOYLE RAY BRADBURY WILLIAM BRADFORD ANNE BRADSTREET NORMAN BRIDWELL JOSEPH BRODSKY LOUIS BROMFIELD GERALDINE BROOKS GWENDOLYN BROOKS CHARLES BROCKDEN BROWN DEE BROWN MARGARET WISE BROWN STERLING A. BROWN WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT PEARL S. BUCK EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS OCTAVIA BUTLER ROBERT OLEN BUTLER TRUMAN CAPOTE ERIC CARLE RACHEL CARSON RAYMOND CARVER JOHN CASEY ANA CASTILLO WILLA CATHER MICHAEL CHABON RAYMOND CHANDLER JOHN CHEEVER MARY CHESNUT CHARLES W. CHESNUTT KATE CHOPIN SANDRA CISNEROS BEVERLY CLEARY BILLY COLLINS INA COOLBRITH JAMES FENIMORE COOPER HART CRANE STEPHEN CRANE ROBERT CREELEY VÍCTOR HERNÁNDEZ CRUZ COUNTEE CULLEN E.E. CUMMINGS MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM RICHARD HENRY DANA JR. EDWIDGE DANTICAT REBECCA HARDING DAVIS HAROLD L. DAVIS SAMUEL R. DELANY DON DELILLO TOMIE DEPAOLA PETE DEXTER JUNOT DÍAZ PHILIP K. DICK JAMES DICKEY EMILY DICKINSON JOAN DIDION ANNIE DILLARD W.S. DI PIERO E.L. DOCTOROW IVAN DOIG H.D. (HILDA DOOLITTLE) JOHN DOS PASSOS FREDERICK DOUGLASSOur THEODORE Mission DREISER ALLEN DRURY W.E.B. -

The Fiction of Ellen Douglas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "All This World Is Full of Mystery": The icF tion of Ellen Douglas. Elizabeth Wilkinson Tardieu Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Tardieu, Elizabeth Wilkinson, ""All This World Is Full of Mystery": The ictF ion of Ellen Douglas." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6284. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6284 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced bom the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sectionssm all withoverlaps. -

Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 1987

1989: Spartina by John Casey 2016: The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 1988: Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 2015: All the Light We Cannot See by A. Doerr 1987: Paco’s Story by Larry Heinemann 2014: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 1986: World’s Fair by E. L. Doctorow 2013: Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2012: No prize awarded 2011: A Visit from the Goon Squad “Established in 1950, the National Book Award is an 1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist by Jennifer Egan American literary prize administered by the National 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization.” 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout - from the National Book Foundation website. 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien by Junot Diaz 2017: Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2016: The Underground Railroad by Colson 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks Whitehead 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2004: The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay The Hair of Harold Roux 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride by Thomas Williams 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1973: Chimera by John Barth Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 1972: The Complete Stories 2000: Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 2009: Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann by Flannery O’Connor 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 2008: Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen 1971: Mr. -

Your Name Here

ELLEN GILCHRIST AND ANNE SEXTON: SYMPATHY AND SELF-KNOWLEDGE, REVISION AND REDEMPTION by LYDIA WHITT RICE (Under Direction the of HUGH RUPPERSBURG) ABSTRACT Ellen Gilchrist's work, in its images, themes and techniques, responds to the life and work of Anne Sexton. Using Gilchrist's own comments, as well as extensive textual evidence from Gilchrist's poetry and fiction, I argue that Gilchrist's work is, at least in part, motivated and sustained by her interest in creating a critical space in which Sexton's work can be re-evaluated. Although Sexton was only seven years older than Gilchrist, the timing of their careers is crucial to their success: for Sexton, who began writing in 1956 and committed suicide in 1974, the second wave of the American Women's Movement and the raising of the collective cultural consciousness that it brought came too late. In contrast, Gilchrist began her professional writing career in 1978, just in time to experience the benefits brought by the movement that Sexton had missed. Throughout her work, Gilchrist pays homage to Sexton and illuminates the contexts in which Sexton's works were created, offering the contemporary reader fresh insight into what Gilchrist perceives of as the previously-dismissed works of Sexton. Gilchrist's writing works toward this end in a variety of ways. In her first novel, The Annunciation, Gilchrist imaginatively recreates many of Sexton's experiences, leading the reader to identify and sympathize with a woman in Sexton's historical milieu as she emerges as a writer. In much of her subsequent fiction, Gilchrist proceeds to explore several of the darker issues that led to Sexton's demise and ultimate critical dismissal, including the debilitating nature of mental illness and the inefficacy of psychotherapy and patriarchal religion to respond. -

Columbia Companion to the Twentieth-Century American Short Story

THE COLUMBIA COMPANION TO THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN SHORT STORY Blanche H. Gelfant, Editor Lawrence Graver, Assistant Editor Columbia university press new york CONTENTS Introduction PARTI. Thematic Essays The American Short Story Cycle 9 The American Short Story, 18oj— 1900 The African American Short Story The Asian American Short Story 34 The Chicano-Latino Short Story 42 The Ecological Short Story S° Lesbian and Gay Short Stories S6 The Native American Short Story 64 Non-English American Short Stories 72 The American Working-Class Short Story 81 American Short Stories of the Holocaust 94 [VI] CONTENTS PART II. Individual Writers Ray Bradbury (1920— ) and Their Work 162 Alice Adams (1926— 1999) Kate Braverman (i9S°— ) 166 1 Sherwood Anderson (1876— 1941) Larry Brown (19S — ) 109 IJ2 James Baldwin (1924— 198J) Erskine Caldwell (1903— 198J) 114 '7S John Barth (1930— ) Hortense Calisher (1911— ) 180 "7 Donald Barthelme (1931— 1989) Truman Capote (1924— 1984) 121 184 Rick Bass (19S9— ) Raymond Carver (193 8— 1988) 12J 188 Richard Bausch (1945— ) Willa Cather (1873— 1947) 130 '93 Charles Baxter (1947— ) John Cheever (1912— 1982) '3S 199 Ann Beattie (1947— ) Sandra Cisneros (19S4— ) '38 Saul Bellow (1915— ) Walter Van Tilburg Clark (1909—1971) '44 209 Gina Berriault(i926— ) Elizabeth Cook-Lynn (1930— ) 149 211 Doris Betts (1932— ) Robert Coover (1932— ) 152 21S Paul Bowles (1910— 1999) Lydia Davis (194J— ) IS4 219 Kay Boyle (1902— 1992) Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni (19S3— ) 223 CONTENTS [VII] Andre Dubus (1936— 1999) Mary Hood (1946— ) 226 297 Deborah Eisenberg (1946— ) Langston Hughes (1902— 1967) 234 300 Stanley Elkin (1930— 199S) Zora Neale Hurston (1891— i960) 239 3OS George P. -

Mary A. Mccay English Department 931 Nashville Ave

Mary A. McCay English Department 931 Nashville Ave. Loyola University New Orleans, LA 70115 New Orleans, LA 70118 (504) 891-4107 (504) 865-3389 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (504) 865-2294 EDUCATION: • Tufts University, Ph.D. English and American Literature. Dissertation: Women in the Novels of Charles Brockden Brown: A Study. • Boston College, M.A. English. Thesis: The Film Scripts of James Agee. • Catholic University of America, A.B., magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, English/History. Undergraduate Thesis: The Visions of William Butler Yeats CURRENT POSITION: Loyola University, New Orleans, LA. Professor Director of The Walker Percy Center for Writing and Publishing, Moon and Verna Landrieu Distinguished Teaching Professor, Professor of English. Co-Advisor of American Studies Minor. Director, Loyola Irish Studies Summer Program, Trinity College, Dublin. Co- Director, Loyola Americans in Paris Summer Program, Liaison for the Keele University Exchange Program, Liaison for the University of Nijmegen Exchange Program. Initiatives Developed as Interim Dean: • Common Curriculum renumbering • Yearly evaluation and raises for extraordinary faculty • HNS handbook acceptance Initiatives Developed as Chair: • Developed web page template for Departmental SACS review 2005. • Planned and developed (with the French Department) the Paris Summer Program. I Direct the program. • Planned and developed the Loyola Irish Studies Summer Program. I direct that program at Trinity College Dublin. • Planned and Developed the Loyola-Keele University Exchange Program in the UK. I am the liaison with Keele University International Office. Planned and developed the Loyola-Radboud University Exchange Program in the Netherlands. I am the liaison for that program. • Directed the departmental in-depth review. -

Gender Issues in Ellen Gilchrist Karon Reese University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2013 Occupying the Pedestal: Gender Issues in Ellen Gilchrist Karon Reese University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reese, Karon, "Occupying the Pedestal: Gender Issues in Ellen Gilchrist" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 967. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/967 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Occupying the Pedestal: Gender Issues in Ellen Gilchrist Occupying the Pedestal: Gender Issues in Ellen Gilchrist A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English By Karon Reese Bachelor of Arts in English, 2001 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in English, 2004 University of Arkansas December 2013 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________ Professor Susan Marren Dissertation Director ___________________________ ____________________________________ Professor Keith Booker Professor Joseph Candido Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Ellen Gilchrist’s work shows the struggles of women living in a postmodern South. This dissertation explores Gilchrist’s representations of southern women as they transition from the old South to modernity. Gilchrist’s work depicts women who attempt to break off the pedestal of white Southern womanhood, but never quite do, often simultaneously disrupting and confirming traditional notions of a “good Southern lady.” Gilchrist shows how women occupy the pedestal as a form of refuge and also as a form of protest.