Using Yoga for Healing: the Ayurvedic Basis of Hatha Yoga Practices by Sarasvati Buhrman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoga Studies Major (BA)

Yoga Studies Major (BA) • TRA463 Meditation in Yogic and Tantric Traditions: A Practicum (3) "The technique of a world-changing yoga has to be as uniform, Anatomy sinuous, patient, all-including as the world itself. If it does not deal with Choose 3 Credits all the difficulties or possibilities and carefully deal with each necessary • PAR101 Experiential Anatomy (3) element, does it have any chance of success?"—Sri Aurobindo • PSYB332 Human Anatomy (3) A Bachelor of Arts degree (120 credits) consists of Core Curriculum (30 credits) and at least one major (36–60 credits), as well as Language minors and/or elective courses of the student’s choosing. • REL355 Introductory Sanskrit: The Language of the Gods (3) Naropa University's Yoga Studies program is dedicated to the Enrichment Electives education, preservation, and application of the vast teachings Choose 6 credits of yoga. The program offers a comprehensive study of yoga's • PSYB304 Somatic Intelligence: The Neuroscience of Our history, theory, and philosophy, as well as providing an in-depth Body-Mind Connection (3) immersion and training in its practice and methodologies. Balancing • REL210 Religion & Mystical Experience (3) cognitive understanding with experiential learning, students study • REL247 Embodying Sacred Wisdom: Modern Saints (3) the transformative teachings of yogic traditions while gaining the • REL277 Sanskrit I (4) necessary knowledge and skills to safely and effectively teach • REL334 Hindu Tantra (3) yoga. • REL351 Theories of Alternative Spiritualities and New Religious The curriculum systematically covers the rich and diverse history, Movements (3) literature, and philosophies of traditions of yoga, while immersing • TRA100 Shambhala Meditation Practicum (3) students in the methodologies of Hatha yoga, including asana, • TRA114 Indian Devotional and Raga Singing (3) pranayama, and meditation. -

Yoga Makaranda Yoga Saram Sri T. Krishnamacharya

Yoga Makaranda or Yoga Saram (The Essence of Yoga) First Part Sri T. Krishnamacharya Mysore Samasthan Acharya (Written in Kannada) Tamil Translation by Sri C.M.V. Krishnamacharya (with the assistance of Sri S. Ranganathadesikacharya) Kannada Edition 1934 Madurai C.M.V. Press Tamil Edition 1938 Translators’ Note This is a translation of the Tamil Edition of Sri T. Krishnamacharya’s Yoga Makaranda. Every attempt has been made to correctly render the content and style of the original. Any errors detected should be attributed to the translators. A few formatting changes have been made in order to facilitate the ease of reading. A list of asanas and a partial glossary of terms left untranslated has been included at the end. We would like to thank our teacher Sri T. K. V. Desikachar who has had an inestimable influence upon our study of yoga. We are especially grateful to Roopa Hari and T.M. Mukundan for their assistance in the translation, their careful editing, and valuable suggestions. We would like to thank Saravanakumar (of ECOTONE) for his work reproducing and restoring the original pictures. Several other people contributed to this project and we are grateful for their efforts. There are no words sufficient to describe the greatness of Sri T. Krishna- macharya. We began this endeavour in order to better understand his teachings and feel blessed to have had this opportunity to study his words. We hope that whoever happens upon this book can find the same inspiration that we have drawn from it. Lakshmi Ranganathan Nandini Ranganathan October 15, 2006 iii Contents Preface and Bibliography vii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Why should Yogabhyasa be done . -

Pranayama Redefined/ Breathing Less to Live More

Pranayama Redefined: Breathing Less to Live More by Robin Rothenberg, C-IAYT Illustrations by Roy DeLeon ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 REMEMBERING OUR ROOTS “When Prana moves, chitta moves. When prana is without movement, chitta is without movement. By this steadiness of prana, the yogi attains steadiness and should thus restrain the vayu (air).” Hatha Yoga Pradipika Swami Muktabodhananda Chapter 2, Verse 2, pg. 150 “As long as the vayu (air and prana) remains in the body, that is called life. Death is when it leaves the body. Therefore, retain vayu.” Hatha Yoga Pradipika Swami Muktabodhananda Chapter 2, Verse 3, pg. 153 ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 “Pranayama is usually considered to be the practice of controlled inhalation and exhalation combined with retention. However, technically speaking, it is only retention. Inhalation/exhalation are methods of inducing retention. Retention is most important because is allows a longer period for assimilation of prana, just as it allows more time for the exchange of gases in the cells, i.e. oxygen and carbon dioxide.” Hatha Yoga Pradipika Swami Muktabodhananda Chapter 2, Verse 2, pg. 151 ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 Yoga Breathing in the Modern Era • Focus tends to be on lengthening the inhale/exhale • Exhale to induce relaxation (PSNS activation) • Inhale to increase energy (SNS) • Big ujjayi - audible • Nose breathing is emphasized at least with inhale. Some traditions teach mouth breathing on exhale. • Focus on muscular action of chest, ribs, diaphragm, intercostals and abdominal muscles all used actively on inhale and exhale to create the ‘yoga breath.’ • Retention after inhale and exhale used cautiously and to amplify the effect of inhale and exhale • Emphasis with pranayama is on slowing the rate however no discussion on lowering volume. -

History Name What Has Become Known As "Kundalini Yoga" in The

History Name What has become known as "Kundalini yoga" in the 20th century, after a technical term peculiar to this tradition, has otherwise been known[clarification needed] as laya yoga (?? ???), from the Sanskrit term laya "dissolution, extinction". T he Sanskrit adjective ku??alin means "circular, annular". It does occur as a nou n for "a snake" (in the sense "coiled", as in "forming ringlets") in the 12th-ce ntury Rajatarangini chronicle (I.2). Ku??a, a noun with the meaning "bowl, water -pot" is found as the name of a Naga in Mahabharata 1.4828. The feminine ku??ali has the meaning of "ring, bracelet, coil (of a rope)" in Classical Sanskrit, an d is used as the name of a "serpent-like" Shakti in Tantrism as early as c. the 11th century, in the Saradatilaka.[3] This concept is adopted as ku??alnii as a technical term into Hatha yoga in the 15th century and becomes widely used in th e Yoga Upanishads by the 16th century. Hatha yoga The Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad is listed in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads. S ince this canon was fixed in the year 1656, it is known that the Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad was compiled in the first half of the 17th century at the latest. The Upanishad more likely dates to the 16th century, as do other Sanskrit texts whic h treat kundalini as a technical term in tantric yoga, such as the ?a?-cakra-nir upana and the Paduka-pañcaka. These latter texts were translated in 1919 by John W oodroffe as The Serpent Power: The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga In this b ook, he was the first to identify "Kundalini yoga" as a particular form of Tantr ik Yoga, also known as Laya Yoga. -

A Brief Introduction to Ayurveda

Ayurveda A Brief Introduction and Guide by Vasant Lad, B.A.M.S., M.A.Sc. Ayurveda is considered by many scholars to be the Energy is required to create movement so that fluids oldest healing science. In Sanskrit, Ayurveda means “The and nutrients get to the cells, enabling the body to Science of Life.” Ayurvedic knowledge originated in function. Energy is also required to metabolize the India more than 5,000 years ago and is often called the nutrients in the cells, and is called for to lubricate and “Mother of All Healing.” It stems from the ancient Vedic maintain the structure of the cell. Vata is the energy of culture and was taught for many thousands of years in an movement, pitta is the energy of digestion or metabolism oral tradition from accomplished masters to their and kapha, the energy of lubrication and structure. All disciples. Some of this knowledge was set to print a few people have the qualities of vata, pitta and kapha, but one thousand years ago, but much of it is inaccessible. The is usually primary, one secondary and the third is usually principles of many of the natural healing systems now least prominent. The cause of disease in Ayurveda is familiar in the West have their roots in Ayurveda, viewed as a lack of proper cellular function due to an including Homeopathy and Polarity Therapy. excess or deficiency of vata, pitta or kapha. Disease can also be caused by the presence of toxins. The Strategy: Your Constitution and Its Inner Balance In Ayurveda, body, mind and consciousness work Ayurveda places great emphasis on prevention and together in maintaining balance. -

Ayurveda, Yoga, Sanskrit, & Vedic Astrology. Ayur = Life/Living Ve

Ayurveda & Yoga The branches of Vedic Sciences are: Ayurveda, Yoga, Sanskrit, & Vedic Astrology. Ayur = life/living Veda=knowledge/science Ayurveda, the Science of life, is often called “the Mother of All Healing” and is recognized by the World Health Organization as the worlds oldest continually practiced form of medicine in human history. The teachings were passed down orally until 300 BCE when they were written down into two main texts, Caraka Samhita & Sushruta Samhita. “Ayurveda emphasizes preventative and healing therapies along with various methods of purification and rejevenation. Ayurveda is more than a mere healing system, it is a science and an art of appropriate living that helps to achieve longevity. It can guide evey individual in the proper choice of diet, living habits and exercise to restore balance in the body, mind and consciousness, thus preventing disease from gaining a foothold in the system.” ~ Dr. Vasant Lad, The Ayurvedic Institute The three principles of energy in Ayurveda are Vata (air/space), Pitta (fire/water) & Kapha (earth/water). Vata is the energy of movement, Pitta is the energy of transformation, Kapha is the energy of lubrication and form. We all express qualities from each dosha, generally with a primary, secondary and less prominent dosha. According to Ayurveda, disease is caused by imbalance, which can be caused by excess or deficiency or toxins. Toxins are called “ama”, and according to Ayurveda, ama is the cause of all disease. Vata, composed of Air/Ether governs breathing, blinking, heart-beat, all movements through cellular membrane. In balance Vata creates creativity and flexibility. Imbalanced Vata creates fear, nervousness & anxiety. -

Introduction to Yoga

Introduction to Yoga Retreat Handbook 2018 www.PureFlow.Yoga | [email protected] The Guest House This being human is a guest house. Every morning a new arrival. A joy, a depression, a meanness, some momentary awareness comes as an unexpected visitor. Welcome and entertain them all! Even if they are a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture, still, treat each guest honorably. He may be clearing you out for some new delight. The dark thought, the shame, the malice. meet them at the door laughing and invite them in. Be grateful for whatever comes. because each has been sent as a guide from beyond. - Rumi www.PureFlow.Yoga | [email protected] Contents Part 1: Intro to Yoga Philosophy I. What is Yoga? II. The Practices of Yoga III. Many Paths, One Destination IV. The 8 Limbs of Yoga: Ashtanga Yoga Part 2: The Practices: I. Yamas & Niyamas: Disciplines and Ethics for Freedom II. Asana: a. Sun Salutations b. Alignment Principles c. Developing a Home Practice III. Pranayama IV. Meditation V. Bhakti: Mantra & Kirtan VI. Mudra VII. Sadhana Practice Guide Part 3: Energy Anatomy: I. The Gunas: Sattva, Rajas, & Tamas II. The 5 Koshas III. The 7 Chakras IV. Living Holistically & in Balance Part 4: Ayurveda: Wisdom of Life and Longevity I. Panchabhuta: The 5 Elements II. Ayurvedic Food combining III. Doshas: Elemental constitutions/ Quiz Part 5: Playbook I. Mandala Meditation II. Intention / Sankalpa VIII. Gratitude IX. Reflection & Integration X. Notes & Inspirations XI. Recommended Reading, Viewing & Listening XII. Sangha Love “Do your practice and all is coming”. -

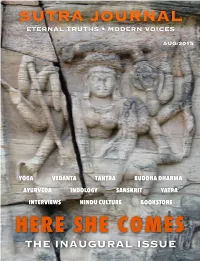

The Inaugural Issue Sutra Journal • Aug/2015 • Issue 1

SUTRA JOURNAL ETERNAL TRUTHS • MODERN VOICES AUG/2015 YOGA VEDANTA TANTRA BUDDHA DHARMA AYURVEDA INDOLOGY SANSKRIT YATRA INTERVIEWS HINDU CULTURE BOOKSTORE HERE SHE COMES THE INAUGURAL ISSUE SUTRA JOURNAL • AUG/2015 • ISSUE 1 Invocation 2 Editorial 3 What is Dharma? Pankaj Seth 9 Fritjof Capra and the Dharmic worldview Aravindan Neelakandan 15 Vedanta is self study Chris Almond 32 Yoga and four aims of life Pankaj Seth 37 The Gita and me Phil Goldberg 41 Interview: Anneke Lucas - Liberation Prison Yoga 45 Mantra: Sthaneshwar Timalsina 56 Yatra: India and the sacred • multimedia presentation 67 If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him Vikram Zutshi 69 Buddha: Nibbana Sutta 78 Who is a Hindu? Jeffery D. Long 79 An introduction to the Yoga Vasistha Mary Hicks 90 Sankalpa Molly Birkholm 97 Developing a continuity of practice Virochana Khalsa 101 In appreciation of the Gita Jeffery D. Long 109 The role of devotion in yoga Bill Francis Barry 113 Road to Dharma Brandon Fulbrook 120 Ayurveda: The list of foremost things 125 Critics corner: Yoga as the colonized subject Sri Louise 129 Meditation: When the thunderbolt strikes Kathleen Reynolds 137 Devata: What is deity worship? 141 Ganesha 143 1 All rights reserved INVOCATION O LIGHT, ILLUMINATE ME RG VEDA Tree shrine at Vijaynagar EDITORIAL Welcome to the inaugural issue of Sutra Journal, a free, monthly online magazine with a Dharmic focus, fea- turing articles on Yoga, Vedanta, Tantra, Buddhism, Ayurveda, and Indology. Yoga arose and exists within the Dharma, which is a set of timeless teachings, holistic in nature, covering the gamut from the worldly to the metaphysical, from science to art to ritual, incorporating Vedanta, Tantra, Bud- dhism, Ayurveda, and other dimensions of what has been brought forward by the Indian civilization. -

Prana and Pranayama Swami Niranjananda

Prana and Pranayama Swami Niranjanananda Saraswati Yoga Publications Trust, Munger, Bihar, India © Bihar School of Yoga 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Yoga Publications Trust. The terms Satyananda Yoga® and Bihar Yoga® are registered trademarks owned by International Yoga Fellowship Movement (IYFM). The use of the same in this book is with permission and should not in any way be taken as affecting the validity of the marks. Published by Yoga Publications Trust First edition 2009 ISBN: 978-81-86336-79-3 Publisher and distributor: Yoga Publications Trust, Ganga Darshan, Munger, Bihar, India. Website: www.biharyoga.net www.rikhiapeeth.net Printed at Thomson Press (India) Limited, New Delhi, 110001 Dedication In humility we offer this dedication to Swami Sivananda Saraswati, who initiated Swami Satyananda Saraswati into the secrets of yoga. II. Classical Pranayamas 18. Guidelines for Pranayama 209 19. Nadi Shodhana Pranayama 223 20. Tranquillizing Pranayamas 246 21. Vitalizing Pranayamas 263 Appendices A. Supplementary Practices 285 B. Asanas Relevant to Pranayama 294 C. Mudras Relevant to Pranayama 308 D. Bandhas Relevant to Pranayama 325 E. Hatha Yoga Pradipika Pranayama Sutras 333 Glossary 340 Index of Practices 353 General Index 357 viii Introduction he classical yogic practices of pranayama have been Tknown in India for over 4,000 years. In the Bhagavad Gita, a text dated to the Mahabharata period, the reference to pranayama (4:29) indicates that the practices were as commonly known during that period as was yajna, fire sacrifice. -

The Sikh Foundations of Ayurveda

Asian Medicine 4 (2008) 263–279 brill.nl/asme The Sikh Foundations of Ayurveda Neil Krishan Aggarwal Abstract This paper explores how Sikh scriptures establish a unique claim to Ayurvedic knowledge. After considering Ayurvedic creation myths in the classical Sanskrit canon, passages from Sikh liturgi- cal texts are presented to show how Ayurveda is refashioned to meet the exigencies of Sikh theol- ogy. The Sikh texts are then analysed through their relationship with general Puranic literatures and the historical context of Hindu-Sikh relations. Finally, the Indian government’s current propagation of Ayurveda is scrutinised to demonstrate its affiliation with one particular religion to the possible exclusion of others. The Sikh example provides a glimpse into local cultures of Ayurveda before the professionalisation and standardisation of Ayurvedic practice in India’s post-independence period and may serve as a model for understanding other traditions. Keywords Ayurveda, Hindu and Sikh identity, Sanskritisation, Dasam Granth, Udasis, Sikhism Scholars of South Asia who study Ayurveda have overwhelmingly concen- trated on the classical Sanskrit canon of Suśruta, Caraka, and Vāgbhata.̣ This paper departs from that line of inquiry by examining the sources for a Sikh Ayurveda. Sikh religious texts such as the Guru Granth Sahib and the Dasam Granth contest the very underpinnings of Ayurveda found in Sanskrit texts. Historical research suggests that the Udāsī Sikh sect incorporated these two scriptures within their religious curriculum and also spread Ayurveda throughout north India before the post-independence period. The rise of a government-regulated form of Ayurveda has led to the proliferation of pro- fessional degree colleges, but the fact that Udāsī monasteries still exist raises the possibility of a continuous medical heritage with its own set of divergent practices. -

Mantra and Yantra in Indian Medicine and Alchemy

Ancient Science of Life Vol. VIII, Nos. 1. July 1988, Pages 20-24 MANTRA AND YANTRA IN INDIAN MEDICINE AND ALCHEMY ARION ROSU Centre national de la recherché scientifique, Paris (France) Received: 30 September1987 Accepted: 18 December 1987 ABSTRACT: This paper was presented at the International Workshop on mantras and ritual diagrams in Hinduism, held in Paris, 21-22 June1984. The complete text in French, which appeared in the Journal asiatique 1986, p.203, is based upon an analysis of Ayurvedc literature from ancient times down to the present and of numerous Sanskrit sources concerning he specialized sciences: alchemy and latrochemisry, veterinary medicine as well as agricultural and horticulture techniques. Traditional Indian medicine which, like all possession, were deeply rooted in their Indian branches of learning, is connected consciousness. The presence of these in with the Vedas and him Atharvaveda in medical literature is less a result of direct particular, is a rational medicine. From the Vedic recollections than of their persistence time of he first mahor treatises, those of in the Hindu tradition, a fact to which testify Caraka and Susruta which may be dated to non-medical Sanskrit texts (the Puranas and the beginning of the Christian era, classical Tantra) with regard to infantile possession. Ayurveda has borne witness to its scientific Scientific doctrines and with one another in tradition. While Sanskrit medical literature the same minds. The general tendency on bears the stamp of Vedic speculations the part of the vaidyas was nevertheless to regarding physiology, its dependence on limit, in their writings, such popular Vedic pathology is insignificant and wholly contributions so as to remain doctrines of negligible in the case of Vedic therapeutics. -

Download the Book from RBSI Archive

About this Document by A. G. Mohan While reading the document please bear in mind the following: 1. The document seems to have been written during the 1930s and early 40s. It contains gems of advice from Krishnamacharya spread over the document. It can help to make the asana practice safe, effective, progressive and prevent injuries. Please read it carefully. 2. The original translation into English seems to have been done by an Indian who is not proficient in English as well as the subject of yoga. For example: a. You may find translations such as ‘catch the feet’ instead of ‘hold the feet’. b. The word ‘kumbhakam’ is generally used in the ancient texts to depict pranayama as well as the holdings of the breath. The original translation is incorrect and inconsistent in some places due to such translation. c. The word ‘angulas’ is translated as inches. Some places it refers to finger width. d. The word ‘secret’ means right methodology. e. ‘Weighing asanas’ meaning ‘weight bearing asanas’. 3. While describing the benefits of yoga practice, asana and pranayama, many ancient Ayurvedic terminologies have been translated into western medical terms such as kidney, liver, intestines, etc. These cannot be taken literally. 4. I have done only very minimal corrections to this original English translation to remove major confusions. I have split the document to make it more meaningful. 5. I used this manuscript as an aid to teaching yoga in the 1970s and 80s. I have clarified doubts in this document personally with Krishnamacharya in the course 2 of my learning and teaching.