Journal Pre-Proof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Chief Electoral Officer, Telangana

MOST URGENT G.E. TO THE LOK SABHA - 2019 Bv E-mail / Speed Post OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER, TELANGANA GENERAL ADMTN|STRAT|ON (ELECTTONS) DEPARTMENT 5th Floor, Buddha Bhavan, MCH Building, Ranigunj Road, Secunderabad -500003 Memo No.675'l/Elecs.A/2O1 9-26 Dated:30-06-2021 Sub : - Elections - General Elections to the Lok Sabha - 2019 - Election Expenses accounts of 68 numbers of defaulted candidates contested from 04-Nizamabad Parliamentary Constituency - Disqualification Orders of the Election Commission dated. 23-06-2021 published in Telangana Gazette No. 25 dated. 26-06-2021 - Copy forwarded for usage in future elections by the ROs and other election related officials - Regarding. Ref : - 1 .Election Commisiion of lndia Order No. 76/TEL -HP/SOU3/2019, dated. 23-06-2021. 2.This office Memo No. 6751/Elecs.tu2019-20 dated. 25-06-202'laddressed to the Commissioner of Printing, Stationary & Stores Purchase, Telangana State, Hyderabad. 3.Telangana Gazette No. 25, dt. 26-06-2021 . -0o0- Copy of Telangana Gazette Part -V Extraordinary No. 25, dated. 26-06-2021 in reference 3'd cited in which Election Commission of lndia Orders dated. 23-06-2021 disqualifying 68 numbers of defaulted candidates under Section 10A of the Representation of People Act, 1951 contested from O4-Nizamabad Parliamentary Constituency during the General Elections to the House of People - 2019 has been published, is sent herewith to all the Collectors & District Election Officers including the Commissioner, GHMC & District Election Officer, Hyderabad district with a request to provide the same to all the Returning Officers of Parliamentary and Assembly Constituencies and other election related officials under their jurisdiction for reference and usage in all the forthcoming elections and also to upload the matter in the district portal for public view. -

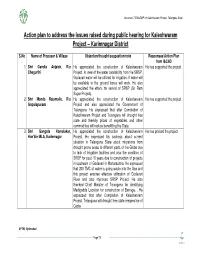

Action Plan to Address the Issues Raised During Public Hearing for Kaleshwaram Project – Karimnagar District

Annexure 7 EIA&EMP for Kaleshwaram Project, Telangana State Action plan to address the issues raised during public hearing for Kaleshwaram Project – Karimnagar District S.No Name of Proposer & Village Objection/thought/suggestion/note Responses/Action Plan . from I&CAD 1. Shri Gandla Anjaiah, R/o He appreciated the construction of Kaleshwaram He has supported the project. Chegurthi Project. In view of the water availability from the SRSP, Godavari water will be utilized for irrigation. If water will be available in the ground bores will work. He also appreciated the efforts for revival of SRSP (Sri Ram Sagar Project). 2. Shri Manda Rajamallu, R/o He appreciated the construction of Kaleshwaram He has supported the project. Gopalapuram Project and also appreciated the Government of Telangana. He expressed that after Completion of Kaleshwaram Project and Telangana will drought free state and thereby prices of vegetables and other commodities will reduce benefitting the State. 3. Shri Gangula Kamalakar, He appreciated the construction of Kaleshwaram He has praised the project. Hon'ble MLA, Karimnagar Project. He expressed his sadness about current situation in Telangana State about migrations from drought prone areas to different parts of the Globe due to lack of Irrigation facilities and also the condition of SRSP for past 10 years due to construction of projects in upstream of Godavari in Maharashtra. He expressed that 200 TMC of water is going waste into the Sea and this project ensures effective utilization of Godavari River and also improves SRSP Project. He also thanked Chief Minister of Telangana for identifying Medigadda Location for construction of Barrage. -

O / O DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER, & Ex Officio, District

O / o DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER, & Ex Officio, District Project Officer, SSA & RMSA NIZAMABAD I. ABOUT US: The School Education Department is the largest department consisting of Primary and Secondary stages, assumes greater significance and aims at imparting minimum and essential general education to all the children in the age group of 6-15 years and to equip them with necessary competencies to shape them as useful and productive citizens. Andhra Pradesh has adopted the national pattern of education i.e. 10+2+3. Out of 10 years of schooling, the first 5 years i.e. Classes I to V constitute the Primary stage, the next two years i.e., Class VI & VII the Upper Primary stage and the remaining 3 years i.e., Classes VIII to X, the Secondary stage. Concerted efforts are made in all the schools in the State with a well-knitted field functionaries monitoring system to take the Education to the nearest place of residence of the school going aged children, even in remote, tribal and hillock areas. Andhra Pradesh has attained 100% access by providing at-least One Primary School with in the reach of one kilo meter. Today any child in any part of Andhra Pradesh can access a school with in one kilometer radius. The Government of Andhra Pradesh in the School Education Department is committed to providing quality education from Class I to X for all the school going age children in the State, including general and linguistic minorities, and other disadvantaged-groups. The main objectives of the School Education Department is:- • Universalisation of -

Draft Electoral Roll of Medak-Nizamabad-Adilabad-Karimnagar Teachers Constituency of the A.P Legislative Council As Published on 15-12-2012

Draft Electoral Roll of Medak-Nizamabad-Adilabad-Karimnagar Teachers Constituency of the A.P Legislative Council as published on 15-12-2012 Polling Station Number : ( 57 ) navipet District: Nizamabad - 18 Zilla Parishad High School (Boys) 10th class "A" Room Sl.No. House address Full Name of the Name of father/ mother / Name of educational Age (Place of ordinary elector husband institution, if any, in residence) which he is teaching (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Mandal : NAVIPET Village: ABBAPUR (B) 3-83/2 Chikkela Arjun Janardhan GJC BHIKNOOR 28 1 JANNEPALLY Mandal : NAVIPET Village: ABBAPUR (M) 2-5/4 Battu Babu Narsaiah ZPHS CHADMAL 43 2 ABBAPUR(M) GANDHARI Mandal : NAVIPET Village: ABHANGAPATNAM 1-56/1 Gajam Naveen Kumar Gajam Ambadas ZPHS NALESHWAR 31 3 ABHANGAPATNAM Mandal : NAVIPET Village: DHARYAPUR 1-16 Alishetty Ravikiran Alishetty Thukaram ZPHS KONDAPUR 27 4 DARYAPUR SIRIKONDA 1-127/1 Silmala Suresh Gangadhar ZPHS BEJJORA 36 5 DARYAPUR Mandal : NAVIPET Village: JANNIPALLE 3-14 Okkerla Rajeshwar Rao Kishan Rao ZPHS GUNJILI 40 6 JANNEPALLY 3-52/1A Babayolla Anil Kumar Bhaskar Rao ZPHS KODAPGAL 32 7 NARAYANAPUR 3-71/5 Chinthakindi Vijay Kumar Anjaiah ZPHS MAMIDIPALLY 53 8 JANNEPALLY 3-94/46/1 Konda Guruva Ramulu ZPHS MARAMPALLY 33 9 BC COLONY JANNEPALLY Mandal : NAVIPET Village: MADDEPALLE 3-45 Vishlavath Vasanth Rao Bhikku APSWRS JR COLLAGE 36 10 MADDEPALLY ARMOOR Mandal : NAVIPET Village: NALESHWAR 2-73 Swarna Latha Sirpa Sirpa Chandraiah GHS BANSWADA 30 11 NALESHWAR 4-88 Tirunagari Prasad Laxmi Narayana ZPHS BADGUNA 37 12 NALESHWAR Mandal : NAVIPET Village: NARAYANPUR 1of 279 Draft Electoral Roll of Medak-Nizamabad-Adilabad-Karimnagar Teachers Constituency of the A.P Legislative Council as published on 15-12-2012 Polling Station Number : ( 57 ) navipet District: Nizamabad - 18 Zilla Parishad High School (Boys) 10th class "A" Room Sl.No. -

IJM), ISSN 0976 – 6502(Print), ISSN 0976 - 6510(Online), Internationalvolume 5, Issue 4, April (2014), Pp

International Journal of Management (IJM), ISSN 0976 – 6502(Print), ISSN 0976 - 6510(Online), INTERNATIONALVolume 5, Issue 4, April (2014), pp. JOURNAL 89-99 © IAEME OF MANAGEMENT (IJM) ISSN 0976-6502 (Print) IJM ISSN 0976-6510 (Online) Volume 5, Issue 4, April (2014), pp. 89-99 © IAEME: www.iaeme.com/ijm.asp © I A E M E Journal Impact Factor (2014): 7.2230 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com A STUDY ON MANAGEMENT OF ZILLAPARISHAD HIGH SCHOOLS IN NIZAMABAD MORTHATI KISHORE DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS MANAGEMENT UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND BUSINESS MANAGEMENT OSMANIA UNIVERSITY, HYDERABAD- 500007 T. SOWMYYA * ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF FORENSIC SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SCIENCE, OSMANIA UNIVERSITY, HYDERABAD- 500007 A. ARUN KUMAR ICSSR DOCTORAL FELLOW, DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, OSMANIA UNIVERSITY, HYDERABAD- 500007 ABSTRACT In India, we have three different types of schools, namely schools that follow state syllabus, schools that follow central syllabus and schools that follow International curriculum. Hence, at any class level, we end up with students who have different levels of academic knowledge. Coming to the rural villages, students who come from economically backward classes are obliged to opt for Government schools due to their financial constraints. The Government schools teach in vernacular medium. For the purpose of present study, the Zilla Parishad high school in Velpur, Armoor, Jakranpally, Bheemgal and Kammarpally mandals of Nizamabad district in Telangana are considered. The students in Zilla Parishad High schools are basically from a weak economic background. Students of these schools are beleaguered with linguistic, social, and financial problems. Teachers who teach in these Zillaparishad High schools should keep these facts in mind while teaching the students. -

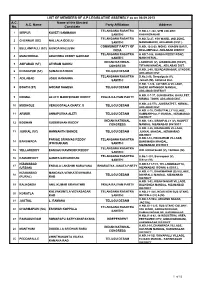

A.C. No. A.C. Name Name of the Elected Candidate Party Affiliation

LIST OF MEMBERS OF A.P.LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY as on 06.09.2013 A.C. Name of the Elected A.C. Name Party Affiliation Address No. Candidate TELANGANA RASHTRA H.NO.2-7-268, SPM COLONY, 1 SIRPUR KAVETI SAMMAIAH SAMITHI KAGHAZNAGAR. TELANGANA RASHTRA H.NO.72-27, 9TH WARD, 2ND ZONE, 2 CHENNUR (SC) NALLALA ODELU SAMITHI MANDAMARRI, ADILABAD (DIST.). COMMUNIST PARTY OF H.NO. 12-2-29, MOHD. KHASIM BASTI, 3 BELLAMPALLI (SC) GUNDA MALLESH INDIA BELLAMPALLI, ADILABAD DISRICT TELANGANA RASHTRA H.NO.7-398, GANGA REDDY ROAD, 4 MANCHERIAL ARAVINDA REDDY GADDAM SAMITHI MANCHERIAL. INDIAN NATIONAL LAXMIPUR (V), GINNEDHARI (POST), 5 ASIFABAD (ST) ATHRAM SAKKU CONGRESS TIRYANI MANDAL, ADILABAD DIST. H.NO. 2-88, SEVADASNAGAR, UTNOOR , 6 KHANAPUR (ST) SUMAN RATHOD TELUGU DESAM ADILABAD DIST. TELANGANA RASHTRA D.No.2-26, Deepaiguda (V), 7 ADILABAD JOGU RAMANNA SAMITHI Jainath (M), Adilabad Dist. H.NO. 1-124, JATHARLA VILLAGE, 8 BOATH (ST) GODAM NAGESH TELUGU DESAM BAZAR HATHNOOR MANDAL, ADILABAD DISTRICT H.NO. 5-7-37, GUNJBAKSH, GAJULPET, 9 NIRMAL ALLETI MAHESHWAR REDDY PRAJA RAJYAM PARTY NIRMAL TOWN, ADILABAD DIST. H.NO. 2-3-573, JUMERATPET, NIRMAL, 10 MUDHOLE VENUGOPALA CHARY. S TELUGU DESAM ADILABAD DIST. H.NO. 8-70, CHOUTPALLY VILLAGE, 11 ARMUR ANNAPURNA ALETI TELUGU DESAM KAMMARPALLY MANDAL, NIZAMABAD DISTRICT INDIAN NATIONAL H.NO. 1-83, SIRANPALLY (V), NAVIPET 12 BODHAN SUDERSHAN REDDY CONGRESS MANDAL, NIZAMABAD DISTRICT H.NO. 2-25, DOANGAON VILLAGE, 13 JUKKAL (SC) HANMANTH SHINDE TELUGU DESAM JUKKAL MANDAL, NIZAMABAD DISTRICT PARIGE SRINIVAS REDDY TELANGANA RASHTRA H.NO.1-12, POCHARAM VILLAGE, 14 BANSWADA BANSWADA MANDAL, (POCHARAM) SAMITHI NIZAMABAD DISTRICT TELANGANA RASHTRA 15 YELLAREDDY EANUGU RAVINDER REDDY R/O. -

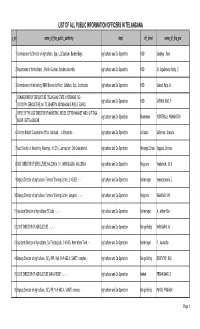

LIST of ALL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS in TELANGANA S No Name of the Public Authority Dept Off Level Name of the Pio

LIST OF ALL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS IN TELANGANA s_no name_of_the_public_authority dept off_level name_of_the_pio 1 Commissioner & Director of Agriculture, Opp. L.B.Stadium, BasheerBagh, - Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD Sandhya , Rani 2 Department of Horticulture, , Public Gurdens, Besides Assembly Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD Sri Jagadeswar Reddy, S 3 Commissioner of Marketing, BRKR Bhavan 1st floor, Saifabad, Opp. Secretariat Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD Samuel Raju, M COMMISSIONER OF SERICULTURE, TELANGANA STATE, HYDERABAD, 8-2- 4 Agriculture and Co-Operation HOD JAYAPAL RAO, P 293/82/PN/SERICULTURE, No. 72, BHARTIYA VIDYABHAVANS PUBLIC SCHOOL OFFICE OF THE ASST DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, BESIDE COTTON MARKET YARD, GUTTALA 5 Agriculture and Co-Operation Khammam VUDUTHALA, PADMAVATHI BAZAR, GUTTALA BAZAR 6 O/o the District Cooperative Office, Adilabad , , Collectorate , Agriculture and Co-Operation Adilabad Gaherwar, Sharada 7 Asst.Director of Marketing, Warangal, 4.1.234, Laxmipuram, Old Grain Market Agriculture and Co-Operation Warangal Urban Vuppala, Srinivas 8 ASST DIRECTOR OF SERICULTURE,NALGONDA, 1-1, MIRIYALGUDA, NALGONDA Agriculture and Co-Operation Nalgonda Venkatesh, Sri B 9 Deputy Director of Agriculture, Farmers Training Centre, 2-10-283, -, - Agriculture and Co-Operation Karimnagar Venkateswarlu, S. 10 Deputy Director of Agriculture, Farmers Training Centre, Suryapet, -, -, - Agriculture and Co-Operation Nalgonda RAMARAJU, KV 11 Assistant Director of Agriculture (BC Lab), -, -, - Agriculture and Co-Operation Karimnagar -

TURMERIC: India Is the Largest Producer, Consumer and Exporter Of

TURMERIC: India is the largest producer, consumer and exporter of turmeric in the world. Indian turmeric is considered to be the best in the world market because of its high curcumin content. India accounts for about 80 per cent of world turmeric production and 60 per cent of world exports.The important turmeric growing States in India are, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Orissa, Maharastra, Assam, Kerala, Karnataka and West Bengal. The market is expected to be valued at more than US$ 1,300 Mn by the end of 2027 the forecast period and is expected to account for a revenue share of little more than 4% by 2027 end. Turmeric has been put to use as a foodstuff, cosmetic, and medicine. It is widely used as a spice in South Asian and Middle Eastern cooking. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) is native to Asia and India. Turmeric is very important spice in India, which produces nearly entire whole world’s crop and consumes 80% of it. India is by far the largest producer and exporter of turmeric in the world. Turmeric occupies about 6% of the total area under spices and condiments in India. Turmeric has been India’s golden spice for the past five centuries. It is one of those few Indian products having both commercials as well as mythological significance. Turmeric is used not only in the culinary item but also as cosmetics in almost every Indian household. Turmeric has been used in Asia for thousands of years and is a major part of Ayurveda, unman, and traditional Chinese medicine. It is used in chemical analysis as an indicator of acidity and alkalinity.The report's analysts forecast the turmeric market in India to grow at a CAGR of 0.97%, in terms of consumption, for the period of 2014-2019 Initiatives of Govt. -

Soil Quality Assessment of Some Turmeric Growing Areas in Relation To

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2019; 8(1): 920-925 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2019; 8(1): 920-925 Soil quality assessment of some turmeric growing Received: 09-11-2018 Accepted: 12-12-2018 areas in relation to root-knot Nematodes status of Nizamabad district of Telangana Ramesh Naik Malavath Dept. of Biotechnology, Telangana University, Nizamabad, Telangana, India Ramesh Naik Malavath and Satyam Raj Thurpu Satyam Raj Thurpu Abstract Dept. of Biotechnology, An investigation was undertaken during kharif, 2018. Twenty eight surface soil samples representing Telangana University, seven turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) growing mandals of Nizamabad districts of Telangana namely Nizamabad, Telangana, India Sirikonda, Armoor, Kammarpally, Velpur, Balkonda, Jakranpally and Dharpally were studied for their physico-chemical properties and fertility status in relations to study molecular investigations on root-knot nematode resistance in turmeric cultivars. The climate of the study area was semi arid and monsoonic climate. The sites selected were confined to nearly level to gently undulating slopes and have granular to sub angular blocky structures. All the soils showed well developed structural variation and exhibited granular to sub angular blocky structure. The soil texture varied from sandy loam to clay. The sand, silt and clay content ranges from 18.2 to 71.4, 4.4 to 18.7 and 20 to 68.2, per cent respectively. The, pH, EC, 2+ 2+ -1 OC, CaCO3, exchangeable Ca and Mg and available N, P, K 6.5 to 8.1, 0.12 to 0.36 dSm , 4.6 to 7.0 gkg-1, 1.1 to 5.0 gkg-1, 6.2 to 21.8 c mol (p+) kg-1, 2.9 to 14.7 c mol (p+) kg-1, 198 to 285 kg ha-1, 14.0 to 34.0 kg ha-1 and 232 to 393 kg ha-1 respectively. -

Nizamabad District, Andhra Pradesh

For Official Use Only CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER BROCHURE NIZAMABAD DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH SOUTHERN REGION HYDERABAD September 2013 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER BROCHURE NIZAMABAD DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH (AAP-2012-13) By G. PRAVEEN KUMAR Assistant Hydrogeologist SOUTHERN REGION BHUJAL BHAWAN, GSI Post, Bandlaguda NH.IV, FARIDABAD-121001 Hyderabad-500068 HARYANA, INDIA Andhra Pradesh TEL: 0129-2418518 Tel: 24222508 Gram: Bhumijal Gram: Antarjal GROUND WATER BROCHURE NIZAMABAD DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1. Drainage 1.2. Land use 1.3. Cropping pattern 1.4. Irrigation 1.5. Studies carried out by CGWB 2.0 RAINFALL 3.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO 3.1 Hydrogeology 3.2 Depth to water level 3.3 Ground water resources 3.4 Ground water quality 4.0 STATUS OF GROUND WATER DEVELOPMENT 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 6.0 RECOMMENDATIONS N I Z A M A B A D D I S T R I C T A T A G L A N C E 1. GENERAL Location North Latitude 180 05' 190 00' East Longitude 770 40' 780 37' Geographical area 7956 sq.km Headquarters Nizamabad No. of revenue mandals 36 No. of revenue villages 922 Population (2011) Urban 587800 Rural 1964273 Total 2552073 Population density 321 per sq.km Major rivers Godavari, Manjira, Maneru Soils Black and red Agroclimatic zone Zone-10-Northern Telangana zone 2. RAINFALL Actual Rainfall 845 mm 3. LAND USE (2012) (Area in ha.) Forest 1,69,343 Barren and uncultivated 46,833 Cultivable waste 13,093 Current fallows 59,068 Net area sown 3,37,329 4. -

Heat Wave Burns Telugu States

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 Published From *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 162 NATION 5 MONEY 6 HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable RISING PRICES EMERGE AS THE NEXT MAMATA'S OBSTRUCTIONIST MINDSET BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH BHUBANESWAR BIG HURDLE FOR ECONOMIC REBOUND DEPRIVED BENGAL OF JOBS: MODI RANCHI DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA VISAKHAPATNAM HYDERABAD, SUNDAY APRIL 4, 2021; PAGES 10+16 `5 SMASH-HIT VAKEEL SAAB TRAILER 10 www.dailypioneer.com ROBOT ARTIST EYEING MUSIC CAREER BSF HANDS OVER BOY TO PAK WHO EGYPT'S SUEZ CANAL AUTHORITY ‘KILL THE BILL' RALLIES ACROSS BRITAIN AFTER SELLING ART FOR $688,888 CROSSED OVER ‘INADVERTENTLY' SAYS SHIPPING BACKLOG CLEARED AGAINST PROPOSED ANTI-PROTEST LAW ophia is a robot of many talents she speaks, jokes, sings and he BSF on Saturday said it has handed over an eight-year- he maritime traffic jam on both ends of the Suez Canal undreds of demonstrators joined marches and rallies even makes art. In March, she caused a stir in the art world old boy to Pakistani rangers, after he inadvertently crossed eased further on Friday, four days after the dislodging of a across Britain on Saturday as part of a “national Swhen a digital work she created as part of a collaboration Tthe international border and reached India's Barmer sector. Tmassive containership that had blocked the waterway, Hweekend of action” against a proposed new law that was sold at an auction for USD 688,888 in the form of a non- The incident took place at the border security fence near authorities said.On Monday, salvage teams freed the would give police extra powers to curb protests.The Police, fungible token (NFT).