St. Johns River Quality, Algae Status and Action Plan by the Jacksonville Waterways Commission St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Communities Trust Annual Report 2016-2017

Florida Communities Trust Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016-2017 Office of Operations Land and Recreation Grants Section Florida Department of Environmental Protection September 30, 2017 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard, MS 103 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 www.dep.state.fl.us Florida Communities Trust Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016-2017 1 Table of Contents LETTER FROM THE CHAIR ....................................................................................................... 1 PROJECT LOCATION MAP ........................................................................................................ 2 FLORIDA COMMUNITIES TRUST .............................................................................................. 3 MISSION AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS ......................................................................................... 4 PARK HAPPENINGS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016-2017 ................................................................ 8 ACQUIRED PROJECTS BY COUNTY 1991-2017 .................................................................... 12 SUMMARY OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES ................................................................................... 29 FLORIDA COMMUNITIES TRUST BOARD MEMBERS ............................................................ 31 Front Cover Photo: Victory Pointe Park (f.k.a. West Lake Park) Unique Abilities 2017 Cycle FCT # 16-005-UA17, City of Clermont, FL Back Cover Photo: Myers-Stickel Property Unique Abilities 2017 Cycle FCT # 16-012-UA17, St. Lucie County, FL Florida Communities Trust -

Water Resources of Duval County, Florida

Water Resources of Duval County, Florida By G.G. Phelps U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 93-4130 Prepared in cooperation with the City of Jacksonville, Florida Tallahassee, Florida 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center Suite 3015 Open-File Reports Section 227 N. Bronough Street Box 25286, MS 517 Tallahassee, FL 32301 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 II CONTENTS Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................1 Purpose and Scope.....................................................................................................................................1 Study Area and Population........................................................................................................................2 Water Use in Duval County ......................................................................................................................4 The Hydrologic Cycle ...............................................................................................................................6 -

Federal Register/Vol. 78, No. 30/Wednesday, February 13, 2013

10072 Federal Register / Vol. 78, No. 30 / Wednesday, February 13, 2013 / Rules and Regulations * Elevation in feet (NGVD) + Elevation in feet (NAVD) # Depth in feet Flooding source(s) Location of referenced elevation above ground Communities affected ∧ Elevation in me- ters (MSL) modified Polecat Branch ......................... At the confluence with Maple Creek ................................... +112 Unincorporated Areas of Nash County. Approximately 0.8 mile upstream of the confluence with +120 Polecat Branch Tributary. Sapony Creek ........................... Approximately 200 feet upstream of Sandy Cross Road +132 Unincorporated Areas of (Secondary Road 1717). Nash County. Approximately 1,550 feet upstream of NC Highway 58 ..... +145 Stony Creek .............................. Approximately 0.5 mile downstream of Red Oak Road +130 City of Rocky Mount, Town (Secondary Road 1003). of Nashville. Just upstream of U.S. Route 64 ......................................... +152 Swift Creek ............................... Approximately 1.8 miles downstream of the Edgecombe +88 City of Rocky Mount, Unin- County boundary. corporated Areas of Nash County. At Red Oak Road (Secondary Road 1003) ........................ +131 Tar River ................................... Approximately 150 feet downstream of South Old Car- +133 City of Rocky Mount, Unin- riage Road. corporated Areas of Nash County. Approximately 0.64 mile downstream of U.S. Highway 64 +162 * National Geodetic Vertical Datum. + North American Vertical Datum. # Depth in feet above ground. ∧ Mean Sea Level, rounded to the nearest 0.1 meter. ADDRESSES City of Rocky Mount Maps are available for inspection at the Planning Department, 331 South Franklin Street, Rocky Mount, NC 27802. Town of Nashville Maps are available for inspection at the Town Hall, 499 South Barnes Street, Nashville, NC 27856. Town of Red Oak Maps are available for inspection at the Town Hall, 8406 Main Street, Red Oak, NC 27868. -

Essential Fish Habitat Assessment

APPENDIX L ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT (PHYSICAL HABITAT) JACKSONVILLE HARBOR NAVIGATION (DEEPENING) STUDY DUVAL COUNTY, FLORIDA THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT ASSESSMENT JACKSONVILLE HARBOR NAVIGATION STUDY DUVAL COUNTY, FL Final Report January 2011 Prepared for: Jacksonville District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Prudential Office Bldg 701 San Marco Blvd. Jacksonville, FL 32207 Prepared by: Dial Cordy and Associates Inc. 490 Osceola Avenue Jacksonville Beach, FL 32250 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................. III LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... III 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 2.0 ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT DESIGNATION ................................................................. 6 2.1 Assessment ........................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Managed Species .................................................................................................. 8 2.2.1 Penaeid Shrimp .................................................................................................. 9 2.2.1.1 Life Histories ............................................................................................... 9 2.2.1.1.1 Brown Shrimp ...................................................................................... -

Town of 120076 Jacksonville Beach, City of 120078 Jacksonville, City of 120077 Neptune Beach, City of 120079

DUVAL COUNTY, FLORIDA (ALL JURISDICTIONS) Volume 3 of 6 COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ATLANTIC BEACH, CITY OF 120075 *BALDWIN, TOWN OF 120076 JACKSONVILLE BEACH, CITY OF 120078 JACKSONVILLE, CITY OF 120077 NEPTUNE BEACH, CITY OF 120079 * NO SPECIAL FLOOD HAZARD AREAS IDENTIFIED Effective: June 3, 2013 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 12031CV003A Duval County, Florida (All Jurisdictions) NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this Preliminary FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision (LOMR) process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS components. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map panels for this community contain the most current information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map panels (e.g., floodways and cross sections). In addition, former flood hazard zone designations have been changed as follows. Old Zone(s) -

Reportr E Sunes

REPORTR ESUNES ED 012 612 THE FIGHT FOR CLEANWATER. BY SCHOONOVER, ROBERT A. FLORIDA ST. BOARD OFHEALTH, JACKSONVILLE PUS DATE JAN 67 EDRS PRICE MF--$0.50 HC.-$472 118P. DESCRIPTORS- *COMMUNITY HEALTHSERVICES, HEALTH, HEALTH SERVICES, HEALTHCONDITIONS, *PUBLIC HEALTH,*SANITATION IMPROVEMENT, SANITATION,*WATER RESOURCES, JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA THIS PUBLICATION DISCUSSESIN DEPTH THE PROBLEM OF WATER POLLUTION AS SEEN DY THE FLORIDASTATE BOARD OF HEALTH. DOMESTIC SEWAGE, INDUSTRIAL WASTES,AND ALLEVIATION' ACTIVITIES OF THE STATE BOARDOF HEALTH AND COUNTY HEALTH DEPARTMENTS ARE DESCRIBED.SIX APPENDIXES PRESENT CORRESPONDENCE AND REPORTSREGARDING THE PROBLEM. THIS IS AN ISSUE OF "FLORIDA HEALTHNOTES," VOLUME 59, NUMBER 1,JANUARY 1967.(SF) e U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROMTHE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. r eselg.":2 A. V. -...111111r P lished by RDA STE BOARD: OF HEAL* ItrA -,11#111.4ti -ti iLskt 4t 1.1 44$4c gel 411, 11( " )i kt ,4 4,ti,11 /'41A 4 The State Board of Health needs additional resources to keep ahead of the state's expanding population and industrial growth which threat- ens Florida's natural beauty.(Cover photograph) Whether or notBilly catches a fish depends upon the amount of pollution dumped into these waters by cities and industry. ^-7, /op CLEAN WATER FLORIDA HEALTH NOTES Published monthly by the Florida State Board of Health, Wilson T. Sowder, M.D., M.P.H., State Health Officer.Publication office, Box 210, Jacksonville, Florida 32201. -

Caloosahatchee Named America's 7Th Most Endangered River Activists Hold Press Conference Today in Fort Myers

Florida Sportsman http://www.floridasportsman.com/casts/060420/ Caloosahatchee Named America's 7th Most Endangered River Activists Hold Press Conference Today in Fort Myers American Rivers, a leader in the movement to reform the Army Corps of Engineers, named the Caloosahatchee River America's 7 th most endangered river, mainly because of damages from massive releases of polluted water from Lake Okeechobee. The St. Lucie River on the east coast is caught up in identical problems due to discharges from the lake into the St. Lucie Canal. The two estuaries were hit with a total of 855 billion gallons of the dirty water last year. Residents in Martin County were warned not to make contact with the water. The Rivers Coalition in Martin County plans legal action and supporting activity to curtail the discharges (see www.riverscoalition.org). While the St. Lucie dumps massive nutrient-laden, freshwater discharges into estuaries and reef-rich coastal waters on the East Coast of the state, the South Florida Water Management District (District) and the Army Corps of Engineers use the canalized Caloosahatchee River to unload massive quantities of foul runoff into the Caloosahatchee estuary. As a result, massive fish kills have occurred, and critical nursery habitats for gamefish have been lost. The Caloosahatchee Association (www.caloosahatchee.org) and American Rivers representatives are enabling concerned citizens to send electronic letters demanding positive action. Visit www.americanrivers.org, and click on Take Action. Top Ten Endangered Rivers Pajaro River, California Upper Yellowstone River, Montana Willamette River, Oregon Salmon Trout River, Michigan Shenandoah River, Virginia, West Virginia Boise River, Idaho Caloosahatchee River, Florida Bristol Bay Watershed, Arkansas San Jacinto River, Texas Verde River, Arizona FS . -

Minutes of the Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, State Of

987 INDEX Volume 39 1972-1974 A & D, Inc., permit, Highlands County 455,497 Acme Fish Co. marina, Palm Beach County 227 Acquisition land, Ten Thousand Islands 403 Adair & Brady: R." M. Wright dredge, Palm Beach Co. 41 Adams, A. A: Gen. Tel. Co., Sarasota County 746 Adams, A. Maitland, dredged material, Monroe Co. 343, 566-8,596 Adamson, Andrew, Indian Lake permit 236 729 A. Duda & Sons agric . lease, Palm Beach Co. Aerial photography, O.P.S. funds 735 Aerojet-General Corp., Dade County land, litigation 128-9 Agreements D.O.T., F.C.D., S.C.R.R., Palm Beach County land 6 Lindrick Corp., boundary line, Pasco County 204 McFadden, W. A., Hutchinson Island, St. Lucie Co. 828-9 Tampa Elec . Co. 61 Windsor Trust (Estero Bay land) 238 Agrico Chemical Company permit 929 Ahern, F. L. , dredge, Duval County 219 Al Pflueger Art. Reef, Dade County 921 Alachua County Bond, Dumont, et al, land sale 837 -8 Bond, Roger, Murphy Act land sale 560 County detention site land 526 County permit , Lake Santa Fe 99 D.O.T. lease, warehouse 71 Gainesville city utilities easement 724 Gilmore, T. , Murphy Act land sale 628 Hadley, R. V., Murphy Act land sale 668 Henderson, R. L., Murphy Act land sale 773-4 Lewis, N.M., Murphy Act land sale 520 Matthews, J. H. , Hardship Act sale 55 Matthews, J. L. , Murphy Act land sale 919 McDavid, Lucille B. , Hardship Act sale 54 Merry, R. 0., Murphy Act land sale 716 Mount Olive Church, Hardship Act sale 45 Road right of way easement 170 Shaw, Lila F., land sale 774 Sutton, Harold J. -

5/31/2014 (Year 3) City of Jacksonville/FDOT NPDES Permit

Part V. 2013/2014 Annual Monitoring Plan Report 6/1/2013 – 5/31/2014 (Year 3) City of Jacksonville/FDOT NPDES Permit 1 2013/2014 Annual Monitoring Plan Report 6/1/2013 – 5/31/2014 (Year 3) City of Jacksonville/FDOT NPDES Permit EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Goal I of the monitoring plan is to identify water quality problem areas. This portion of the plan is implemented by the Routine Tributary Program (continuously in effect since the 1970’s) and the Tributary BMAP I and II Monitoring Program (Begun in 2010). Before the BMAP monitoring began, the Tributary Intensive program was in effect from 2002 to 2006. Routine Tributary Monitoring includes sampling 103 sites quarterly for fecal coliform bacteria and field parameters. Having a long-term dataset is necessary in determining long-term trends, particularly for fecal coliform compliance, which has demonstrated the most dramatic changes. In 2013/2014, the City of Jacksonville continued to play a leadership role in the Lower St. Johns River Tributaries Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) Working Group. Under the direction of FDEP, this group has developed BMAPs for 25 of the fecal coliform impaired WBIDs in Duval County. The City of Jacksonville is responsible for sampling five fecal coliform impaired WBIDs at 12 stations for the Trib I BMAP; and five fecal coliform impaired WBIDs at 18 sites for the Trib II BMAP. (Sites are periodically added, deleted, and changed based on decisions by the TAT Working Group). Extra efforts this year included conducting inter-agency Walk-the-WBIDs or “walks” in each of the ten BMAP I waterbodies. -

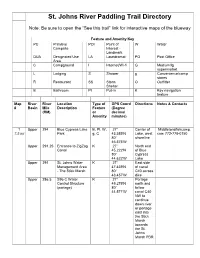

St. Johns River Blueway by Dean Campbell River Overview

St. Johns River Paddling Trail Directory Note: Be sure to open the “See this trail” link for interactive maps of the blueway Feature and Amenity Key PC Primitive POI Point of W Water Campsite Interest - Landmark DUA Designated Use LA Laundromat PO Post Office Area C Campground I Internet/Wi-fi G Medium/lg supermarket L Lodging S Shower g Convenience/camp stores R Restaurant SS Storm O Outfitter Shelter B Bathroom PI Put-in K Key navigation feature Map River River Location Type of GPS Coord Directions Notes & Contacts # Basin Mile Description Feature (Degree (RM) or decimal Amenity minutes) 1 Upper 294 Blue Cypress Lake B, PI, W, 27° Center of Middletonsfishcamp. 7.5 mi Park g, C 43.589'N Lake, west com 772-778-0150 80° shoreline 46.575'W Upper 291.25 Entrance to ZigZag K 27° North end Canal 45.222'N of Blue 80° Cypress 44.622'W Lake Upper 291 St. Johns Water K 27° East side Management Area 47.439'N of canal - The Stick Marsh 80° C40 across 43.457'W dike Upper 286.5 S96 C Water K 27° Portage Control Structure 49.279'N north and (portage) 80° follow 44.571'W canal C40 NW to continue down river or portage east into the Stick Marsh towards the St. Johns Marsh PBR Upper 286.5 St. Johns Marsh – B, PI, W 27° East side Barney Green 49.393'N of canal PBR* 80° C40 across 42.537'W dike 2 Upper 286.5 St. Johns Marsh – B, PI, W 27° East side 22 mi Barney Green 49.393'N of canal *2 PBR* 80° C40 across day 42.537'W dike trip Upper 279.5 Great Egret PC 27° East shore Campsite 54.627'N of canal 80° C40 46.177'W Upper 277 Canal Plug in C40 K 27° In canal -

Anglian Rivers Sea Trout Project Phase 1 Report

Anglian Rivers Sea Trout Project Phase 1 Report This report is the result of research commissioned by the Anglian Sea Trout Project partnership and was funded by the Environment Agency. Published by: Author(s): Anglian Sea Trout Project partnership, c/o lead partner: Mike Pawson Wild Trout Trust, PO Box 120, Waterlooville PO8 0WZ. Tel. 023 9257 0985. www.wildtrout.org Dissemination Status: Publicly available All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced Keywords: with prior permission of the Anglian Sea Trout Project Sea trout, Anglian, Norfolk, Stiffkey, Glaven, Burn, partnership. Nar, Great Eau The views and statements expressed in this report are Research Contractor: those of the author alone. The views or statements Dr. Mike Pawson, 3 Dickens Court, Blundeston, expressed in this publication do not necessarily Lowestoft, Suffolk NR32 5BA: [email protected] represent the views of the Anglian Sea Trout Project partnership and the Anglian Sea Trout Project Environment Agency’s Project Manager: partnership cannot accept any responsibility for such Ros Wright, Senior Fisheries Technical Specialist, views or statements. Anglian Region. Collaborator(s): Wild Trout Trust ,PO Box 120, Waterlooville PO8 0WZ. Tel. 023 9257 0985 ii Anglian Rivers Sea Trout Project – Phase 1 Report Executive summary The Anglian Rivers Sea Trout Project aims to use the collaborative efforts of many sectors of the angling, fishery science and management, conservation and landowning communities to identify actions required to facilitate conservation of sea trout stocks in four north Norfolk Rivers, the Glaven, Stiffkey, Burn and Nar, and the Great Eau in Lincolnshire, and to deliver a prioritised programme of sea trout conservation projects to improve production of sea trout through habitat management. -

Technical Publication SJ97-1 by Christine Adamus David Clapp Stephen Brown St. Johns River Water Management District Palatka, Fl

Technical Publication SJ97-1 SURFACE WATER DRAINAGE BASIN BOUNDARIES ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT: A REFERENCE GUIDE by Christine Adamus David Clapp Stephen Brown St. Johns River Water Management District Palatka, Florida 1997 Northwest Florida----.-------.- Water Management District Suwannee River Water Management District s .... ,St. .Johns River Water Management District South Florida Water Management District The St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) was created by the Florida Legislature in 1972 to be one of five water management districts in Florida. It includes all or part of 19 counties in northeast Florida. The mission of SJRWMD is to manage water resources to ensure their continued availability while maximizing environmental and economic benefits. It accomplishes its mission through regulation; applied research; assistance to federal, state, and local governments; operation and maintenance of water control works; and land acquisition and management. Technical Publications are published to disseminate information collected by SJRWMD in pursuit of its mission. Copies of this report can be obtained from: ~----------------------------------~ Library St. Johns River Water Management District P.O. Box 1429 Palatka, FL 32178-1429 Phone: (904) 329-4132 Contents CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................. vii INTRODUCTION