Walking with Witches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designer Shopping and Country Living Pdf to Download

Designer shopping and country living Braintree and Great Dunmow routes Total distance of main route is 87km/54miles Cobbs 1 7 5 5 Fenn A Debden 0 B1053 0 1 1 1 Short rides B B 0 1 T B1 7 HA 05 XTED 3 RO A A 9.5km/5.9miles D R i v A B 1 e 1 1 r 24 8 P Finchingfield B 32.8km/20.5miles B 4 a 1 n 3 t 83 Debden C 8.9km/5.5miles Green 51 Hawkspur 10 Green B B 7 1 A 5 0 11 D 23.5km/14.7miles 0 5 2 1 1 3 B 4 3 1 Widdington A E 20km/12.5miles Thaxted Wethersfield 7 F 12.8km/8miles 1 0 Little Bardfield 1 Blackmore A G 13.8km/8.6miles 2 End B ROAD 105 H 32.4km/20.2miles BARDFIELD Great 3 Bardfield I 12.6km/7.9miles 1 m 5 B a 0 7 iver C 1 05 R 1 8 1 B 4 J 14km/8.8miles Cherry Green B Gosfield HALSTEAD N Rotten ORTH HAL End L RD 1 05 1 B1 3 Richmond’s S 1 Attractions along this route H A Shalford A Green L FO RD R Holder’s OA 1 Broxted Church D B r Green Monk 1 e 0 5 2 Henham lm Street Great Bardfield Museum Visitor Centre e 3 h . C 3 1 R Saling Hall Garden 5 7 B 0 1 1 0 B 1 8 1 4 Blake House Craft Centre E 4 1 B A M N A 0 1 L 5 I B1 3 L 0 1 51 S 3 5 L B1051 M A The Flitch Way R 57 LU O 10 P A LU B B D 6 B Great Notley Country Park & Discovery Centre E 1 Lindsell A RHE DGE R GA O L S i L R AD L L N v Broxted LO EN L L A E 7 Braintree District Museum WS GRE IN E e Elsenham D S r Duton Hill P High 1 a 5 1 8 n Garrett Warner Textile Archive Gallery 0 3 Bardfield t 1 1 B Saling A 9 Freeport B B 1 1 0 0 5 10 5 Cressing Temple 7 B PI 3 3 1 L T OO S 8 W 2 R Folly Elsenham 4 O 11 AD 3 Green Pleshey Castle 1 B105 B A Great 12 Hatfield Forest R O Saling B -

Essex a Gricu Ltural Society

Issue 27 Welcome to the Essex Agricultural Society Newsletter September 2016 Rural Question Time 20 April Regardless of the outcome of the referendum on 23rd June, one thing our On Wednesday, the Essex Agricultural farming and rural business clients can Society hosted an important rural question depend on is the continued support of time at Writtle College on the facts behind Gepp & Sons, providing specialist and the 'Brexit' debate and the impact on practical advice on a wide range of legal agriculture and the rural economy. issues. The high profile panel included former NFU CLA East Regional Director Ben Underwood President Sir Peter Kendall; former Minister said: “To campaign or govern without of State for Agriculture and Food Sir Jim giving answers on how the rural economy Paice; CLA East Regional Director Ben will be sustained in the future, whether we Underwood, and the UKIP Leader of leave or remain, undermines confidence Norfolk County Council Richard Coke. and gives concern as to the future security of the rural economy. “The CLA wants Ministers to confirm whether they are prepared for all eventualities following the EU Referendum: if the UK votes to leave, the uncertainties for farming and other rural businesses are immediate and need to be addressed swiftly; if we vote to remain, there are still critical commitments that Ministers will The event was ably chaired by NFU need to make before the next Common Vice-Chairman and Essex farmer, Guy Agricultural Policy budget is agreed in 2020. Smith. “We’re not telling our members how to The timely debate came in the wake of vote, but we make it very clear that we will demands by farmers for more information be fighting to defend their interests about how agriculture would be affected if whatever the outcome. -

Relay 100 Legs Document

Leg Distance From To Number (miles) 8 Most Holy Redeemer, Harold Hill St Dominic, Harold Hill 1.3 9 St Dominic, Harold Hill Corpus Christi, Collier Row 2.9 17 Our Lady and St George, Walthamstow Our Lady of the Rosary and St Patrick, Walthamstow and then to St Joseph, Leyton 3.5 18 St Joseph, Leyton Holy Trinity and St Augustine C of E, Leytonstone and then to St Francis of Assisi, 3.7 Stratford 21 Our Lady of Compassion, Upton Park Chapel of the Annunciation, Canning Town and then to St Margaret and All Saints, Canning 1.9 Town 67 St Cuthbert, Burnham-on-Crouch English Martyrs, Danbury 14.8 70 The Holy Family and All Saints, Witham St John Houghton, Tiptree 7.4 77 St Mary and St Michael C of E, Manningtree St Mary the Virgin C of E, Ardleigh 4.1 (Mistley) 78 St Mary the Virgin C of E, Ardleigh St Joseph, Colchester 3.7 82 St Bernard, Coggeshall St Mary Immaculate and the Holy Archangels, 3.2 Kelvedon 83 St Mary Immaculate and the Holy Archangels, St Mary, Silver End 3.7 Kelvedon 85 Our Lady Queen of Peace, Braintree St Francis of Assisi, Halstead 5.9 87 St Peter’s C of E, Sible Headingham The Holy Spirit, Great Bardfield 7.3 89 St John the Baptist Anglican Church, Thaxted Our Lady of Compassion, Saffron Walden 11 90 Our Lady of Compassion, Saffron Walden St Theresa of Lisieux, Stansted Mountfitchet 12 93 Our Lady of Lourdes, Hatfield Broad Oak The Assumption of Our Lady, Harlow 6.1 94 The Assumption of Our Lady, Harlow Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow, then to St Thomas 5.3 More, Harlow, then to Holy Cross, Harlow 95 Holy Cross, Harlow St Giles C of E Church Hall, Nazeing 6.2 96 St Giles C of E Church Hall, Nazeing St Thomas More and St Edward, Waltham Abbey 4.5 97 St Thomas More and St Edward, Waltham Abbey The Immaculate Conception, Epping 5.6. -

Cambridge University Rambling Club Easter 2019

Cambridge University Rambling Club Easter 2019 You should bring a packed lunch (unless stated otherwise) and a bottle of water. Strong boots, waterproofs, and warm clothing are also recommended. Your only expense will be the bus or train fare (given below) and our annual £1 membership fee. There is no need to sign up in advance to join any of this term’s walks – just turn up at the time and place given (with the exception of the Varsity March, see the description below). For more information, please explore our website and Facebook page at: www.srcf.ucam.org/curac & www.facebook.com/cambridgerambling If you have any questions, feel free to email the Club’s President, Benjamin Marschall, at: [email protected] Hills in Bedfordshire Saturday 27th April 23 km / 14 miles Benjamin Marschall: bm515 We will visit some hills in southern Bedfordshire, which are part of the Chilterns. From Stopsley, on the edge of Luton, we climb to the summits of Warden Hill and Galley Hill, with fine views of the area. Along the John Bunyan Trail we will continue to the Barton Hills and the Pegsdon Hills Nature Reserve, before descending to Great Offley for our bus and train home. Meet: 9:05 at the railway station for the 9:24 train to Hitchin Return: 18:06 bus from Great Offley, back in Cambridge by 19:44 Cost: £5.60 with Railcard/GroupSave (£8.50 otherwise) for the train + £6.50 for the bus Orwell river walk: Freston to Shotley Point Saturday 4th May 10 miles / 16 km Pete Jackson: [email protected] An easy 10 mile walk along the scenic and wooded banks of the wide river Orwell to Shotley point from where you get a great view if Harwich and Felixstowe ports. -

7 Manningtree to Flatford and Return

o e o a S a d tr d e e t Recto ry ish Road Hill d Gan Mill Road Warren White Horse Road Wood Barn Hazel Orvi oad d R a Manningtrees to Flatford and return rd o 7 La o f R t n a l e m F a h M ann ingtree R Ded Map of walking routes o ad Braham wood B1070 Spooner's Flatfo Wood rd Road er Sto Riv ur Ba r b ste er e gh The Haugh lch Co Dedham Community Farm ane L Flatford Mill ll E Flatford ll i i s lk B H ffo abergh M s S Su e m N x uff o Ten lk dr B tha reet ing erg n St To Dedham h h ig o Bra H ex lt R Dedham s o s ad E A137 R Riv iv e B1029 e r r S S tour to u r Dedham B O N Forge Street ld River O A C r Judas Gap le o a Ma V w n nin 54 Gates m n gtree d a a S River Stour h t Road d o reet e R r D e r e st t s e e h y c wa h l se c au l o C o C e C h Park Farm T rs H Lane a ope Co l l F le Eas e t L t ill ane H e Great Eastern Main Lin e stle ain Lin a J M upes Greensm C Manningtree astern Manningtree ill H g ill n Great E ll Station i i r H d n e C T o Coxs t S m tation Ro ad a Ea n Ga st C ins La bo ne d h A Q ng Roa East ro u e Lo u v u een n T e g st r a he Ea M h s ad c n w L o ill a h y R H ue D Hill g r il n i He v o l l L e il a May's H th s x Dedham Co Heath Mil Long Road West l H Long Road East ill ad Lawford o Riverview D Church Manningtree B e hall R ar s d g h High School ge ate a C m g h u e L R r Co a n c ne o h a Hil d Road Colchester l e ill v rn Main Li i e r e iv H r D y D r a W t East te e ish a n rav d g u e Hun Cox's ld ters n Wa Cha Gre H se Lawford e d v oa M a Long R y C ich W A137 ea dwa rw ignall B a St t geshall -

Cultural Sites and Constable Country a HA NROAD PE Z E LTO D R T M ROLEA CLO E O

Colchester Town Centre U C E L L O V ST FI K E N IN T R EMPLEW B T ı O R O BO D Cultural sites and Constable Country A HA NROAD PE Z E LTO D R T M ROLEA CLO E O S A T E 4 HE A D 3 CA D 1 D D P R A U HA O A E RO N D A RIAG S Z D O MAR E F OO WILSON W EL IE NW R A TO LD ROAD R EWS Y N R OD CH U BLOYES MC H D L R A BRO C D O R A I OA B D R A E LAN N D N D D R S O WA ROA W D MASON WAY T HURNWO O S S Y O I C A Y N P D TW A133 A I R S D A RD E G N E Colchester and Dedham routes W E CO L O R F VENU W A V R A F AY A AL IN B Parson’s COWDR DR N ENT G R LO C IN O Y A133 A DS ES A D A A Y WAY Heath Sheepen VE T A DR G A K C V OR NK TINE WALK 2 E IV K E D E BA N H IS Bridge NE PME IN I N 3 ON D I L A O R N P G R N C S E ER G G U R S O D E G L S 12 N N UM C MEADOW RD E N B H O IG A R R E E A O OA U U E RS E L C L EN A DI S D V R D R L A A A W D D B E D B K T R G D OA A A C I R L N A D R A 1 G B N ST Y T E D T D O R E 3 Y O A O A E O SPORTSWA A N R O L 4 D HE N U REET M W R R IR O V C AR CO EST FA RD R N T M H E D W G I A P S D C A C H R T T Y I V E ON D BA A E T R IL W E S O N O A B R E RO S T D RI W O M R A D R I O E T R N G C HA L I T STO ROAD U W A AU D E M I C UILDFOR R W G D N O A R SHEE C H ASE O BRIS L RO A E N T D PEN A A O S V A R O P OA D E 7 YC RU A D Y 3 W R C N 1 S E O S RD A RC ELL G D T ) A ES W R S TER S LO PAS D R N H S D G W O BY H E GC ENUE ER E U AV EST EP R RO ORY R E I D E K N N L F Colchester P AT N T IC ra L D R U H Remb S D N e ofnce DLEBOROUGH F E Institute ID H O V M ET LB RE E R A C R'SST C R IFER TE E N L E F D H O H ST -

District Council Annual Report March 2019

District Council Annual Report March 2019 Compiled by Andy Baker, Ward Councillor for Lawford. This will be my last Annual Report for the Ward of Lawford – I am not standing for election in May 2019. Boundary Commission Review/Ward Boundary Changes from 1st May 2019 In 2018 the independent Local Government Boundary Commission for England recommended that the number of Councillors at Tendring District Council (TDC) be reduced, from 60 to 48, which involved the redrawing of Ward Boundaries. Those changes will take place from the local council elections in May 2019 and the Ward of Lawford will be no more. The New Ward of Lawford, Manningtree and Mistley will be a three Member Ward, which means that on Thursday 2nd May 2019 Voters will be required to vote for up to three candidates. There are currently no changes to the three Parish/Town Councils. Local Plan 2013-2033 The Local Plan was submitted in November 2017 and examined in early January 2018. Following that the inspector backed the councils’ submitted figures for housing growth up until 2033 – of 550 new homes each year in Tendring, 716 in Braintree, and 920 in Colchester. His response on housing figures had been delayed from the rest of the Plan after consideration of a late submission from a developer over Tendring’s projected numbers. However, the inspector ruled the councils had accurately predicted housing need based on national guidelines. However he had reservations about the Garden Communities proposals and indicated more work was needed before he could find Part 1 of the Plan sound. -

Colchester Campus Map

Colchester Campus Map 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 E A133 Colchester A133 Clacton LM STE CLINGOE HILL AD ROAD Colchester Entrance A133 A Capon Road Car Park BOUNDARY CAPO O N ROAD ROAD D OA D R IEL SF NE Innovation Car Park 21 Lake House B 28 20 P 19 B Quays Bridge 27 1208 CAPON ROAD North Towers Car Park 18 26 D L 31 OA S R ER LIGHTSHIP WAY W O T 17 16 H BBQ Area 29 T R 30 O 14 N J Wivenhoe House Hotel C and Edge Hotel School 25 G 15 24 23 Brightlingsea 27 13 0 12 1 22 B Wivenhoe Park Day Nursery 11 Visitors’ Reception F A Sports Field Health Centre I D B N M Square 5 Wivenhoe Square 4 Entrance E C Valley Car Park Map Key: H Sports Pavilion Square 3 Square 2 Cycle Path Information Centre E Square 1 Cycle Parking All Weather Pitch VALLEY ROAD K D Bus Stop Essex Sport Arena BOUNDARY ROAD Main Road Tennis Courts 10 Main Squares 9 Sports Centre PARK ROAD 8 Car Park A Path Multi-deck Car Park F 28 Wivenhoe Vehicle Barrier 6 0 1 4 B Wivenhoe Trail Car Park B 1 RIVER COLNE 2 7 Area: 3 5 North Campus G B OU Central Campus ND ARY ROAD South Campus Our Learning Spaces Our Art Spaces Student Residences South Towers (9–10) The Houses (16–21) The Meadows (25–30) Disabled Visitors A Albert Sloman Library (D6) M Art Exchange – Gallery (D6) 9 Bertrand Russell (F6) 16 Anne Knight (C5) 25 Cole (C2) For information on access and parking B The Hex (D5) N Lakeside Theatre (D6) South Courts (1–8) 10 Eddington (E6/F6) 17 Swaynes (C5) 26 Arber (C2) arrangements, please contact Visitors’ C Ivor Crewe Lecture Hall (E6) 1 Harwich (F5/G5) 18 Issac Rebow (B5) 27 Godwin -

The Bromley Messenger March 2016

THE BROMLEY MESSENGER MARCH 2016 Volume 30 No 11 Three little helpers at the tree pruning in Church Meadow during January seeing the numbers already entered for the THE FIRST PAGE Run in April round Little Bromley many of you are pounding the lanes in training. Well! It has been quite a month! It began with the Pride of Tendring awards in the On page 6 following on from my telephone Princes Theatre at Clacton. I know this scam computer scare last month, Pam has sounds like an acceptance speech but I reported on one that she was nearly caught would like to thank you for nominating me, by but which fortunately ended better than it and to even think of nominating me. It did could have done. Pam kept her head but it come as a surprise and I feel very is, sadly, all too easy to be sucked in and honoured. Thank you for all your potentially lose money to the scammers. messages, telephone calls and cards of congratulation; I felt somewhat Which reminds me that by the time you overwhelmed by it all. The evening was read this I will no longer have a telephone great fun and it was lovely meeting all the number with BT. So if you need to other people nominated for their various telephone me the number I am now using deeds in their communities. Fred Nicholls can be found at the back of the magazine. and Jenny, as hosts, were there to greet Thanks to help from my son I have gone everyone’s arrival. -

Weekly List Master Spreadsheet V2

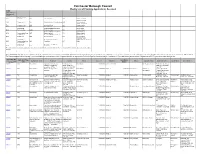

Colchester Borough Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Received NOTE: Application type Codes are as follows: Advertisement ADC Consent MLB Listed Building O99 Outline (Historic) Outline (8 Week COU Change of Use MLD Demolition of a Listed Building O08 Determination) Outline (13 Week ECC County Council MOL Overhead lines O13 Determination) ECM County Matter MPA Prior Approval F99 Full (Historic) Agricultural Reserved Matters (8 Week Full (8 Week MAD Determination MRM Determination) F08 Determination) Reserved Matters (13 Week Full (13 Week MCA Conservation Area MRN Determination) F13 Determination) Certificate of Reserved Matters (16 Week Full (16 Week MCL Lawfulness MRO Determination) F16 Determination) Planning Portal Demolition in Removal/Variation of a Applications (Temporary MDC Conservation Area MRV Condition PX* Code) Government Department Renewal of Temporary MGD Consultation MTP Permission The undermentioned planning applications have been received by this Council under the Town and Country Planning Acts during the week ending: 21/6/19 Where HOUSEHOLDER appears under application detail, the application and any associated Listed Building application can be determined under delegated authority even if objections are received by the Council, unless the application is called in by Members within 21 days of the date at the foot of this list. Please note: 1. The Planning database has now changed - consequently application numbers may no longer be sequential as they are also used for Preliminary Enquiries (not subject to public -

Essex Countryside Cvr Mar1963

THE ILFORD STORY Examining finished plates in the dark room at Messrs. llford Limited. HE story of llford Limited, the range of products with an established reputa quality and reliability. The name, however largest British-owned business en tion for quality throughout the world. stands for much more, and is equally well gaged in the manufacture of photo Credit for the success must go largely to known in the medical, industrial and T graphic materials and equipment. the progressive outlook of the company and scientific worlds, in addition to the adminis dates back to 1879 when Alfred Harman the excellence of its technical achievements. trative side of commerce and industry where first worked in the basement of his own Research laboratories have been established document copying and reproduction systems house in Cranbrook Road, llford, manu at each of the company's production units, are used. facturing dry plates some seven years after three of which are in Essex—at llford, The llford record in the field of nuclear Dr. Maddox invented the dry-plate process. Brentwood and Basildon. research is one of which the company is The demand for these " llford " plates The name llford means for many people justifiably proud. For a number of years became so great that Harman decided to simply a range of amateur films, cameras llford was virtually the sole supplier to the set up his own selling organization, and in and materials which are known for their western world of the special emulsions which 1886 he established the Britannia Works Company. He soon built up a flourishing business and production had to be trans ferred from his own house to larger premises. -

![(ESSEX.] 6 [POST OFFICE DIRECTORY.] James Round, Esq](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6745/essex-6-post-office-directory-james-round-esq-1336745.webp)

(ESSEX.] 6 [POST OFFICE DIRECTORY.] James Round, Esq

(ESSEX.] 6 [POST OFFICE DIRECTORY.] James Round, esq. Birch hall C. J. PheE ps, esq. Briggins park, Herts ORSETT DIVISION. :u.P. Clayton W. F. Glyn, esq. Durrington Wm.Macandrew, esq. Westwood house, house, Sheering Sir Thomas Barrett Lennard, hart. Little H orkesley, Colchester George Alan Lowndes, esq. Great Bar Belhus, Aveley George Hy. Errington, esq. Lexden pk ring-ton ball, Hatfield Broad Oak Richard Baker Wingfield-Baker, esq. HPnry Egc--rton Green, esq. King's ford, Sir Henry John Selwin-Ibbetson, bart. Orsett hall Stanway, Colchester M.P. Down ball, Harlow Russell Champion Bramfill, esq. Stub- John W m.EgertonGreen,esq .Colchester J.Dore Williams,esq.HatfieldBroadOak hers, North Ockendon Charles Henry Hawkins, esq. Mattland J. Duke Hills, esq.Terlings pk. Harlow Rev. William Palin, Stifford rectory house, Colchester R .AthertonAdams esq. Wynters, Harlow Rev. James Rlomfield, Orsett rectory William Henry Penrose, esq. Lower Clerk to the Magistrates, Waiter Rev. JohnWindle,Horndon-on-the- Hill park, Dedbam Charles Metcalfe Rev. Cornwall Smalley, Lit. Thurrock George Edward Tompson, esq.Boxted Assistant Clerk, George Creed John Rayer Hogarth, esq. Heston ball, J. W. Lay, esq. Walcots, Great Tey Petty Sessions are held at Epping Hounslow, Middlesex Rev. W illiam W alsh, Great Tey Police station every friday Rev. Bixby G. Luard, Vicarage,Aveley Charles Robert Bree, M.D., F.L.s. Col• Rev. Wm. Stephen Thomson, Fobbing chester NORTH HINCKFORD Clerk to the Magistrates, North F. D. Bo~gis Rolfe, esq. Wormingford DIVISION. Surridge, Romford Captain Edgar Disney, 10 PriorJ ter- N. C. Barnardiston, esq. Ryes lodge, Petty Sessions are held at Orsett on race, Blotch square, Colchester Little H enny, Sudbury the first friday in every month Edmund Roberts, esq f'.