On Stable HCNO Compounds at High Pressure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

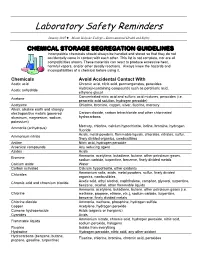

CHEMICAL STORAGE SEGREGATION GUIDELINES Incompatible Chemicals Should Always Be Handled and Stored So That They Do Not Accidentally Come in Contact with Each Other

Laboratory Safety Reminders January 2007 ♦ Mount Holyoke College – Environmental Health and Safety CHEMICAL STORAGE SEGREGATION GUIDELINES Incompatible chemicals should always be handled and stored so that they do not accidentally come in contact with each other. This list is not complete, nor are all compatibilities shown. These materials can react to produce excessive heat, harmful vapors, and/or other deadly reactions. Always know the hazards and incompatibilities of a chemical before using it. Chemicals Avoid Accidental Contact With Acetic acid Chromic acid, nitric acid, permanganates, peroxides Hydroxyl-containing compounds such as perchloric acid, Acetic anhydride ethylene glycol Concentrated nitric acid and sulfuric acid mixtures, peroxides (i.e. Acetone peracetic acid solution, hydrogen peroxide) Acetylene Chlorine, bromine, copper, silver, fluorine, mercury Alkali, alkaline earth and strongly electropositive metals (powered Carbon dioxide, carbon tetrachloride and other chlorinated aluminum, magnesium, sodium, hydrocarbons potassium) Mercury, chlorine, calcium hypochlorite, iodine, bromine, hydrogen Ammonia (anhydrous) fluoride Acids, metal powders, flammable liquids, chlorates, nitrates, sulfur, Ammonium nitrate finely divided organics, combustibles Aniline Nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide Arsenical compounds Any reducing agent Azides Acids Ammonia, acetylene, butadiene, butane, other petroleum gases, Bromine sodium carbide, turpentine, benzene, finely divided metals Calcium oxide Water Carbon activated Calcium hypochlorite, other -

An MC-SCF Study of the Mechanisms for 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions

4642 J. Am. Chem. SOC.1987, 109, 4642-4648 with a = 14.305 A, b = 12.995 A, c = 14.595 A, fi = 93.16O, V = 2709 Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, A’, and Z = 8. and the BASF AG as well as the large-scale preparation of in- A total of 4165 reflections were recorded on a Philips PW 1100 dif- termediate 18 by the Ciba-Geigy AG are gratefully acknowledged. fractometer in the 8-28 scan mode with 28 = 6-46’ using Ka Mo We express our appreciation to Dr. H. Fritz and Dr. D. Hunkler monochromatized radiation (A = 0.709 26 A). The unique reflections were used to solve the structure with MULTAN for NMR and to Dr. J. Worth for MS measurements. 78 programs. The 40 non-hydrogen atoms were anisotropically refined with block diagonal least squares (R = 0.1 10). All 36 hydrogen atoms Registry No. 1, 89683-62-5; 3, 465-73-6; 4,4723-74-4; 5, 72448-17-0; were localized on a F map. The conventional R factor for the 3401 6, 4309-87-9; 9, 108590-43-8; 10, 3647-99-2; 11, 108510-50-5; 12, reflections considered observed with I > 244was 0.052. 65879-03-0; 13, 108510-51-6; 14, 65879-05-2; 15, 65879-04-1; 17, X-ray Crystallographic Analysis for 55. The dimethyl ester crystal- 108510-52-7; 17 (C,-symmetrical isomer), 108510-54-9; 18, 65879-09-6; lized in a monoclinic system, space group P2,/n (No. 14, centrosym- 19, 108510-53-8; 21, 65879-06-3; 26, 108533-20-6; 27, 1076-13-7; 30, metric, racemate), with a = 17.251 A, b = 6.073 A, c = 16.512 A, fi = 108510-55-0; 31, 3648-03-1; 32, 3648-04-2; 40, 65879-07-4; 42, 65879- 92.24’, V = 1729 A3and Z = 4. -

Environmental Health & Safety

Environmental Health & Safety Chemical Safety Program Chemical Segregation & Incompatibilities Guidelines Class of Recommended Incompatible Possible Reaction Examples Chemical Storage Method Materials If Mixed Corrosive Acids Mineral Acids – Separate cabinet or storage area Flammable Liquids Heat Chromic Acid away from potential water Flammable Solids Hydrogen Chloride sources, i.e. under sink Bases Hydrochloric Acid Oxidizers Gas Generation Nitric Acid Poisons Perchloric Acid Violent Phosphoric Acid Reaction Sulfuric Acid Corrosive Bases/ Ammonium Hydroxide Separate cabinet or storage area Flammable Liquids Heat Caustics Sodium Hydroxide away from potential water Flammable Solids Sodium Bicarbonate sources, i.e. under sink Acids Gas Generation Oxidizers Poisons Violent Reaction Explosives Ammonium Nitrate Secure location away from Flammable Liquids Nitro Urea other chemicals Oxidizers Picric Acid Poisons Explosion Hazard Trinitroaniline Acids Trinitrobenzene Bases Trinitrobenzoic Acid Trinitrotoluene Urea Nitrate Flammable Liquids Acetone Grounded flammable storage Acids Fire Hazard Benzene cabinet of flammable storage Bases Diethyl Ether refrigerator Oxidizers Methanol Poisons Heat Ethanol Toluene Violent Glacial Acetic Acid Reaction Flammable Solids Phosphorus Separate dry cool area Acids Fire Hazard Magnesium Bases Heat Oxidizers Violent Poisons Reaction Sodium Hypochlorite Spill tray that is separate from Reducing Agents Fire Oxidizers Benzoyl Peroxide flammable and combustible Flammables Hazard Potassium Permanganate materials Combustibles -

Development of a High-Density Initiation Mechanism for Supercritical Nitromethane Decomposition

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School DEVELOPMENT OF A HIGH-DENSITY INITIATION MECHANISM FOR SUPERCRITICAL NITROMETHANE DECOMPOSITION A Thesis in Mechanical Engineering by Christopher N. Burke © 2020 Christopher N. Burke Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2020 The thesis of Christopher N. Burke was reviewed and approved by the following: Richard A. Yetter Professor of Mechanical Engineering Thesis Co-Advisor Adrianus C. van Duin Professor of Mechanical Engineering Thesis Co-Advisor Jacqueline A. O’Connor Professor of Mechanical Engineering Karen Thole Professor of Mechanical Engineering Mechanical Engineering Department Head ii Abstract: This thesis outlines the bottom-up development of a high pressure, high- density initiation mechanism for nitromethane decomposition. Using reactive molecular dynamics (ReaxFF), a hydrogen-abstraction initiation mechanism for nitromethane decomposition that occurs at initial supercritical densities of 0.83 grams per cubic centimeter was investigated and a mechanism was constructed as an addendum for existing mechanisms. The reactions in this mechanism were examined and the pathways leading from the new initiation set into existing mechanism are discussed, with ab-initio/DFT level data to support them, as well as a survey of other combustion mechanisms containing analogous reactions. C2 carbon chemistry and soot formation pathways were also included to develop a complete high-pressure mechanism to compare to the experimental results of Derk. C2 chemistry, soot chemistry, and the hydrogen-abstraction initiation mechanism were appended to the baseline mechanism used by Boyer and analyzed in Chemkin as a temporal, ideal gas decomposition. The analysis of these results includes a comprehensive discussion of the observed chemistry and the implications thereof. -

![Arxiv:1510.07052V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 23 Oct 2015 99 Lae Ta.20,Adrfrne Therein)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7858/arxiv-1510-07052v1-astro-ph-ep-23-oct-2015-99-lae-ta-20-adrfrne-therein-2397858.webp)

Arxiv:1510.07052V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 23 Oct 2015 99 Lae Ta.20,Adrfrne Therein)

A Chemical Kinetics Network for Lightning and Life in Planetary Atmospheres P. B. Rimmer1 and Ch Helling School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, KY16 9SS, United Kingdom ABSTRACT There are many open questions about prebiotic chemistry in both planetary and exoplane- tary environments. The increasing number of known exoplanets and other ultra-cool, substellar objects has propelled the desire to detect life and prebiotic chemistry outside the solar system. We present an ion-neutral chemical network constructed from scratch, Stand2015, that treats hydrogen, nitrogen, carbon and oxygen chemistry accurately within a temperature range between 100 K and 30000 K. Formation pathways for glycine and other organic molecules are included. The network is complete up to H6C2N2O3. Stand2015 is successfully tested against atmo- spheric chemistry models for HD209458b, Jupiter and the present-day Earth using a simple 1D photochemistry/diffusion code. Our results for the early Earth agree with those of Kasting (1993) for CO2, H2, CO and O2, but do not agree for water and atomic oxygen. We use the network to simulate an experiment where varied chemical initial conditions are irradiated by UV light. The result from our simulation is that more glycine is produced when more ammonia and methane is present. Very little glycine is produced in the absence of any molecular nitrogen and oxygen. This suggests that production of glycine is inhibited if a gas is too strongly reducing. Possible applications and limitations of the chemical kinetics network are also discussed. Subject headings: astrobiology — atmospheric effects — molecular processes — planetary systems 1. Introduction The input energy source and the initial chem- istry have been varied across these different ex- The potential connection between a focused periments. -

Infrared Diode Laser Spectroscopic Study of Combustion Related

INFRARED DIODE LASER SPECTROSCOPIC STUDY OF COMBUSTION RELATED KINETICS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Erik Lee Janssen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department Chemistry and Biochemistry October 2015 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title INFRARED DIODE LASER SPECTROSCOPIC STUDY OF COMBUSTION RELATED KINETICS By Erik Lee Janssen The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: John F. Hershberger Chair Kenton Rodgers Svetlana Kilina Benjamin Braaten Approved: 1/12/16 Gregory Cook Date Department Chair ABSTRACT In the introduction section background into the subject of combustion chemistry is presented. The topics included are combustion mechanisms, combustion pollutants, and infrared absorption spectroscopy. Chapter two describes experiments that probe the kinetics of the reactions of CN radicals with several small primary alcohols, as well as the product channels of the reaction between the CN radical and methanol. It was found that all studied reactions were fast, and that CN preferentially abstracts the methyl hydrogen from methanol. Chapter three describes a study of the product channels of the reaction of the hydroxymethyl radical with nitric oxide. It was found that the primary product was the adduct, with minor channels yielding isocyanic acid and nitroxyl radicals. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the Department of Energy, Grant DE-FG03-96ER14645. -

INCOMPATIBLE CHEMICALS Up-Dated October 2011

INCOMPATIBLE CHEMICALS Up-dated October 2011 Sources Accident Prevention Manual for Industrial Operations, 6th ed., National Safety Council, Fire Protection Guide on Hazardous Materials, 6th ed., National Fire Protection Association; 49CFR173; recent laboratory inspections. Incompatible materials should not be stored together where they can be inadvertently mixed or where a spill or leak can cause danger. General guidelines are: 1. Oxygen and fuels must not be stored together. 2. Water reactive materials are not to be stored with flammables (except where a flammable is used to blanket a material such as sodium and then at least practical quantity), or in an area where they could become wet (under a sink, sprinkler head, shower, etc.) 3. Strong acids and bases are not to be stored together. 4. Materials which can produce poisonous gases must not be stored with products which accelerate the release of the gas. (Examples: cyanogens are not to be stored with an acid, or cleaning products containing chlorine are not to be stored with ammonia.) 5. Explosives (picric acid, etc.) are not to be stored with fuels. 6. Incompatible acids must not be stored together. (Examples: perchloric acid is not to be stored with a reducing agent such as sulfuric acid, as upon mixing, this could produce a shock sensitive explosive; nitric acid and acetic acid, a potential explosive mixture, must not be stored together.) Specific examples of incompatible items likely to be found in laboratories are: Chemical Store Away From or Out of Contact With Acetic Acid Chromic acid, nitric acid, hydroxyl compounds, ethylene glycol, perchloric acid, peroxides and permanganates. -

6.3.1 Examples of Incompatible Chemicals Chemical Incompatible

6.3.1 Examples of Incompatible Chemicals Chemical Incompatible with acetic acid chromic acid, nitric acid, perchloric acid, peroxides, permanganates acetic anhydride Hydroxyl-containing compounds such as ethylene glycol and perchloric acid acetylene chlorine, bromine, copper, fluorine, silver, mercury acetone concentrated nitric and sulfuric acid mixtures alkali and water, carbon tetrachloride or other chlorinated hydrocarbons, carbon alkaline earth dioxide, halogens metals ammonia mercury, chlorine, calcium hypochlorite, iodine, bromine, hydrofluoric acid (anhydrous) (anhydrous) ammonium acids, powdered metals, flammable liquids, chlorates, nitrates, sulfur, finely nitrate divided organic or combustible materials aniline nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide arsenical any reducing agent materials azides acids bromine see chlorine calcium oxide water carbon calcium hypochlorite, all oxidizing agents (activated) carbon sodium tetrachloride chlorates ammonium salts, acids, powdered metals, sulfur, finely divided organic or combustible materials chromic acid acetic acid, naphthalene, camphor, glycerol, alcohol, flammable liquids in and chromium general trioxide chlorine ammonia, acetylene, butadiene, butane, methane, propane or other petroleum gases, hydrogen, sodium carbide, benzene, finely divided metals, turpentine chlorine dioxide ammonia, methane, phosphine, hydrogen sulfide copper acetylene, hydrogen peroxide cumene acids (organic and inorganic) hydroperoxide cyanides acids flammable ammonium nitrate, chromic acid, hydrogen peroxide, nitric -

Chemical Incompatibilities

Chemical Incompatibilities Incompatibilities Chromic acid, nitric acid, hydroxyl compounds, ethylene glycol, Acetic acid perchloric acid, peroxides, permanganates Acetylene Chlorine, bromine, copper, fluorine, silver, mercury Acetone Concentrated nitric and sulfuric acid mixtures Alkali and alkaline earth metals (such as Water, carbon tetrachloride or other chlorinated hydrocarbons, powdered aluminum or magnesium, calcium, carbon dioxide, halogens lithium, sodium, potassium) Mercury (in manometers, for example), chlorine, calcium Ammonia (anhydrous) hypochlorite, iodine, bromine, hydrofluoric acid (anhydrous) Acids, powdered metals, flammable liquids, chlorates, nitrites, Ammonium nitrate sulfur, finely divided organic combustible materials Aniline Nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide Arsenical materials Any reducing agent Azides Acids Bromine See chlorine Calcium oxide Water Carbon (activated) Calcium hypochlorite, all oxidizing agents Carbon tetrachloride Sodium Ammonium salts, acids, powdered metals, sulfur, finely divided Chlorates organic or combustible materials Acetic acid, naphthalene, camphor, glycerol, alcohol, flammable Chromic acid and chromium liquids in general Ammonia, acetylene, butadiene, butane, methane, propane (or Chlorine other petroleum gases), hydrogen, sodium carbide, benzene, finely divided metals, turpentine Chlorine dioxide Ammonia, methane, phosphine, hydrogen sulfide Copper Acetylene, hydrogen peroxide Cumene hydroperoxide Acids (organic or inorganic) Cyanides Acids Ammonium nitrate, chromic acid, hydrogen peroxide, -

Safety Manual > Incompatible Chemicals Partial Listing

LSU University Safety Manual Section VIII, Part C – Incompatible Chemicals Partial Listing Safety Manual > Incompatible Chemicals Partial Listing C. Incompatible Chemicals Partial Listing Chemical Incompatible Chemicals Acetic acid Chromic acid, nitric acid, permanganates, and peroxides Acetic anhydride Hydroxyl containing compounds such as ethylene glycol, perchloric acid Acetone Concentrated nitric acid and sulfuric acid mixtures, hydrogen peroxide Acetylene Bromine, chlorine, copper, fluorine, mercury, and silver Alkaline and alkaline earth metals such as powdered calcium, cesium, lithium, magnesium, potassium, sodium, aluminum, etc. Carbon dioxide, chlorinated hydrocarbons, water, and the halogens (dry sand should be used to extinguish fires) Aluminum and its alloys (particularly powders) Acid or alkaline solutions, ammonium persulfate, water, chlorates, chlorinated compounds, nitrates, and organic compounds in nitrate/nitrite salt baths Ammonia (anhydrous) Bromine, calcium hypochlorite, chlorine, hydrofluoric acid, iodine, mercury, and silver Ammonium nitrate Acids, chlorates, chlorides, lead, metallic nitrates, metal powders, finely divided organics or combustibles, sulfur, and zinc Ammonium perchlorate, permanganate, or persulfate Combustible materials, oxidizing materials such as acids, chlorates, and nitrates Aniline Hydrogen peroxide or nitric acid LSU University Safety Manual Section VIII, Part C – Incompatible Chemicals Partial Listing Barium peroxide Combustible organics, oxidizing materials, water, and reducing agents Bismuth -

VA Baltimore Research Service

VA Baltimore Research Service - Chemical Storage Guidelines Prepared by Grazyna Zaidel, Chemical Hygiene Officer, October 2007 Reviewed by Angela Wood VISN 5 Industrial Hygienist and Dave Pullen VISN 5 Safety and Fire Protection Engineer Safe chemical handling requires routine inspections of chemical storage areas and maintenance of rigorous inventory control. The inherent hazards of chemicals can be reduced by minimizing the quantity of chemicals on hand. Proper storage and handling can reduce or eliminate associated risks. All chemical storage areas and cabinets should be inspected semi-annually and any unwanted or expired chemicals should be removed. For guidance on chemicals purchase and storage limitations please get familiar with entire Chemical Storage Guidance and our Picric Acid, Perchloric Acid, and Ethyl Ether Policies. Typical storage considerations may include temperature, ignition control, ventilation, segregation and identification. Proper segregation is necessary to prevent incompatible materials from inadvertently coming into contact. A physical barrier and/or distance are effective for proper segregation. Proper storage information can be obtained from the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS), or other chemical reference material. As required by 29 CFR 1910.1200, an MSDS must be on hand for every hazardous chemical in your workplace. MSDS must be also provided by the manufacturer or distributor of chemicals purchased. Maximum allowable quantities of flammable and combustible liquids can be obtained by referencing NFPA 99, Standard for Health Care Occupancies and NFPA 45, Standard on Fire Protection for Laboratories Using Chemicals. Considerations for proper storage: • All chemical containers must be labeled in English as to their contents and with appropriate hazard warnings. -

The Ionic Building Blocks of Life: Exploring Astrochemistry Through Mass Spectrometry

THE IONIC BUILDING BLOCKS OF LIFE: EXPLORING ASTROCHEMISTRY THROUGH MASS SPECTROMETRY by Callie A. Cole B.S., Chemistry – ACS Certified University of Montana, Missoula, 2010 Certificate of College Teaching Graduate Teacher Program University of Colorado, Boulder, 2013 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry 2015 This thesis entitled: The Ionic Building Blocks of Life: Exploring Astrochemistry through Mass Spectrometry written by Callie A. Cole has been approved for the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry by: ______________________________________ Veronica M. Bierbaum ______________________________________ Theodore P. Snow ________________________ Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of the scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Cole, Callie A. (Ph.D., Analytical Chemistry) The Ionic Building Blocks of Life: Exploring Astrochemistry through Mass Spectrometry Thesis directed by Dr. Veronica M. Bierbaum ABSTRACT The first polyatomic molecule was discovered in interstellar space in 1968, catalyzing the growth of a new scientific field called astrochemistry. Since its inception, collaborations among laboratory chemists, astrophysical modelers, and observational astronomers in this field have led to the detection of nearly 200 molecules in the interstellar medium (ISM). Similarly, detections of complex biomolecules in cometary dust and meteorites have sparked theories of the origin of terrestrial life, a central focus of the recently-established field of astrobiology. Chemical processing occurs in a variety of environments within our galaxy.