Philanthropy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAF World Giving Index 2015

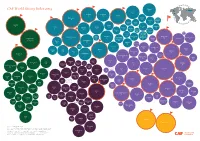

CAF World Giving Index 2015 Finland 31 Sweden 28 Germany Denmark Norway 20 39 TOP 15 Netherlands Belarus 20 7 103 Russian Ukraine Federation Slovakia Latvia 89 129 123 110 Canada Poland Romania 4 Ireland Austria 78 Bulgaria Belgium Kosovo 93 9 23 Hungary 115 48 116 Estonia 124 Lithuania Republic 99 142 of Moldova The former 120 China Serbia Yugoslav 144 118 Czech Slovenia Montenegro Republic of Kyrgyzstan United Kingdom Bosnia and Macedonia Republic of Korea Republic 37 98 Georgia 18 United States 6 Herzegovina 86 Mongolia 64 130 112 of America Luxembourg 88 52 France 2 33 74 Albania 83 Armenia 138 Greece Croatia Tajikistan 140 Kazakhstan 62 73 56 Taiwan Portugal Spain Malta Bhutan 35 82 58 Italy 12 Turkmenistan 71 17 Guatemala 72 Switzerland 16 40 Northern Cyprus Azerbaijan 122 30 Afghanistan Japan 84 Nepal 76 102 Cyprus Senegal Egypt Haiti 42 Puerto Rico 85 112 Iran 59 Morocco Tunisia Thailand 29 Mauritania 126 139 32 19 Dominican Republic 109 Niger 41 Belize 135 Palestinian 70 Mali Iraq Uzbekistan Myanmar Sudan Territory 121 Guinea 141 38 27 1 80 67 Ghana Honduras Chad Sierra Leone 63 Lebanon 60 136 54 Burkina Faso 96 Mexico Nicaragua Jamaica 69 21 104 Hong Kong 90 Ethiopia Democratic South Sudan Bahrain 26 97 Israel 13 127 Republic of Nigeria 68 75 Brazil the Congo El Salvador 43 Cambodia 105 Sri Lanka 117 Jordan 8 100 118 Liberia Congo Costa Rica Cameroon Uruguay 25 91 Malaysia 36 92 77 10 Kenya Philippines Vietnam 46 Panama Uganda 11 United Arab Emirates 79 53 57 14 Kuwait Togo Cote d’Ivoire India Venezuela Namibia 24 133 Benin 107 106 Peru Colombia 128 61 Pakistan 114 132 94 66 145 Ecuador Madagascar Bangladesh Singapore Burundi 95 Indonesia 131 Paraguay Gabon Rwanda 101 34 125 137 Yemen 22 111 143 Saudi Arabia Bolivia Mauritius 47 65 Argentina 45 108 Malawi Zimbabwe 44 87 United Chile Republic 49 of Tanzania Angola Zambia 81 Australia 134 51 5 New Zealand 3 © Charities Aid Foundation 2015 Botswana All rights reserved. -

CAF World Giving Index 2018 Map Prior to Interview: Helping a Stranger, Donating Money and Volunteering Time)

# Country rank based on CAF World Giving Index score. (%) CAF World Giving Index score (calculated as a combined average of the proportion of people who reported one or more of the following in the month CAF World Giving Index 2018 map prior to interview: helping a stranger, donating money and volunteering time). The CAF World Giving Index map is not to scale and country names are indicative of position only. © Charities Aid Foundation 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Countries are ranked based on their 2017 data. Only includes countries surveyed in 2017. 1 Russian Federation 25% 110 Sweden 41% 42 Canada 49% 15 Iceland 48% 17 44 Finland 40% Norway 50% 13 109 Estonia 26% Latvia 19% 137 138 Lithuania* 19% United Kingdom 55% 6 Denmark 46% 24 Poland 24% 112 Ireland 56% 5 22 Germany 46% 121 Belarus 23% 45 Mongolia 39% 88 Slovakia 28% Netherlands 51% 11 Czech Republic 22% 125 United States of 120 Hungary 23% Ukraine 29% Kazakhstan 28% Austria 44% 81 96 America 58% 4 Belgium 41% 39 32 Republic of 129 Serbia 21% 99 Moldova 27% Luxembourg 41% 41 Slovenia 39% 47 55 Kyrgyzstan 36% 66 Kosovo 33% 102 Romania 27% France 32% 132 Croatia 20% Georgia 24% Uzbekistan 36% 72 Montenegro 24% Bulgaria 22% 118 53 116 126 Japan 22% Switzerland 45% Bosnia and 28% 128 26 Herzegovina 90 The former Yugoslav 20% Azerbaijan -

CAF World Giving Index 2012 Denmark 10

CAF World Giving Index 2012 Denmark 10 Finland Estonia Latvia 17 79 Netherlands 74 6 Ireland Lithuania Russian 2 127 105 Belarus Germany Federation Sweden 91 34 Poland Canada 37 94 3 Ukraine 111 Luxembourg Czech Belgium 28 Republic Slovakia Romania 54 98 79 Republic of 119 United Kingdom Moldova 8 88 137 Bulgaria 137 Serbia Kosovo Slovenia The former Mongolia United States 79 Austria 34 Yugoslav Republic Uzbekistan Kazakhstan 46 of America France 104 28 of Macedonia 24 5 54 145 Republic Spain 115 Haiti 132 Hungary 145 Greece of Korea 72 China 67 Dominican Republic 94 Montenegro 141 45 Croatia 115 144 24 Albania Turkmenistan 13 99 119 Italy Bosnia and Tajikistan Mexico 57 Malta Herzegovina Azerbaijan 61 Hong Kong Japan 75 21 76 Kyrgyzstan 19 85 Jamaica Portugal 128 Georgia 32 Armenia 119 Guatemala Trinidad and Tobago Turkey 137 Afghanistan Nepal Syria 48 16 Lebanon Iran 48 115 Taiwan 58 67 12 52 Palestinian Iraq Egypt 123 91 Nicaragua Tunisia Territories Thailand Morocco 126 105 89 94 India 26 Algeria 133 Bangladesh Chad Jordan Bahrain Honduras 125 109 102 110 65 Vietnam 31 Guinea Djibouti Pakistan Niger 70 66 113 85 114 Malaysia 119 Cyprus Panama Sierra Leone Mauritania 21 Qatar 76 58 72 El 33 14 Singapore Cambodia Salvador Venezuela Mali Sudan Somaliland Israel 40 Senegal 108 102 43 (Region) 54 118 27 Costa Rica 123 Sri Lanka 48 15 Ghana United Arab Colombia 44 Emirates 42 Liberia Nigeria Kenya Indonesia Uganda 141 37 Philippines 11 58 40 7 Brazil 46 17 83 Rwanda Ecuador Burkina 128 130 Oman Faso Saudi Arabia 19 Gabon 140 Burundi 87 Bolivia 141 78 Cameroon 61 134 Peru 67 Congo United Republic Togo 83 99 94 Paraguay of Tanzania Benin 130 9 Central 134 Yemen African Argentina Democratic Republic Republic 111 Mozambique 99 93 of the Congo Angola Malawi 30 52 Uruguay Australia Chile 89 Zambia 1 34 37 Comoros Botswana Swaziland 79 New Zealand 105 48 Mauritius 4 23 134 © Charities Aid Foundation 2012 Lesotho 64 Zimbabwe All rights reserved. -

World Giving Index 2016

CAF W RLD GIVING INDEX 2016 The world's leading study of generosity October 2016 Contents Foreword 3 About this report 4 Key findings and conclusions 5 Universal recommendations 7 CAF World Giving Index 2016 map 8 1 Global view 1.1 The CAF World Giving Index Top 20 10 1.2 Global trends across behaviours 13 2 Three giving behaviours 2.1 Helping a stranger 2.1.1 Top 10 countries for helping a stranger, by participation and population 16 2.1.2 Helping a stranger and gender 17 2.1.3 Helping a stranger and age 18 2.2 Donating money to charity 2.2.1 Top 10 countries for donating money, by participation and population 20 2.2.2 Donating money and gender 21 2.2.3 Donating money and age 22 2.3 Volunteering time 2.3.1 Top 10 countries for volunteering time, by participation and population 24 2.3.2 Volunteering time and gender 25 2.3.3 Volunteering time and age 26 3 Continental comparisons 3.1 Continental World Giving Index scores 28 3.2 Continental giving behaviour scores 29 4 Most improved countries 4.1 Most improved countries for 2015 30 4.2 Most improved countries over time 31 Appendices 1 Alphabetical CAF World Giving Index full table 34 2 CAF World Giving Index full table 36 3 Helping a stranger full table 39 4 Donating money full table 41 5 Volunteering time full table 43 6 Methodology 45 7 Surveyed countries 46 Copyright © Charities Aid Foundation 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. -

WORLD GIVING INDEX 2013 a Global View of Giving Trends

WORLD GIVING INDEX 2013 A global view of giving trends December 2013 Registered charity number 268369 Contents Foreword 3 About this report 4 Key findings and conclusions 5 Recommendations 7 World Giving Index 2013 map 8 1 Global view 1.1 The World Giving Index Top 20 10 1.2 Global trends across behaviours 13 2 Three giving behaviours 2.1 Helping a stranger 2.1.1 Top 10 countries for helping a stranger, by participation and population 15 2.1.2 Helping a stranger and gender 16 2.1.3 Helping a stranger and age 17 2.2 Donating money to charity 2.2.1 Top 10 countries for donating money, by participation and population 18 2.2.2 Donating money and gender 19 2.2.3 Donating money and age 20 2.3 Volunteering time 2.3.1 Top 10 countries for volunteering time, by participation and population 21 2.3.2 Volunteering time and gender 22 2.3.3 Volunteering time and age 22 3 Continental comparisons 3.1 Continental World Giving Index scores 24 3.2 Continental giving behaviour scores 25 Appendices 1 Alphabetical World Giving Index full table 26 2 World Giving Index full table 28 3 Helping a stranger full table 31 4 Donating money full table 33 5 Volunteering time full table 35 Methodology 37 Surveyed countries 38 Copyright © Charities Aid Foundation 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. -

CAF WORLD GIVING INDEX 2015 a Global View of Giving Trends

CAF WORLD GIVING INDEX 2015 A global view of giving trends November 2015 Registered charity number 268369 WGI2015_Report_PRESS_0915.indd 1 28/10/2015 12:52:04 Contents Foreword 3 About this report 4 Key findings and conclusions 5 Universal recommendations 7 CAF World Giving Index 2015 map 8 1 Global view 1.1 The CAF World Giving Index Top 20 10 1.2 Global trends across behaviours 13 2 Three giving behaviours 2.1 Helping a stranger 2.1.1 Top 10 countries for helping a stranger, by participation and population 16 2.1.2 Helping a stranger and gender 17 2.1.3 Helping a stranger and age 18 2.2 Donating money to charity 2.2.1 Top 10 countries for donating money, by participation and population 19 2.2.2 Donating money and gender 20 2.2.3 Donating money and age 21 2.3 Volunteering time 2.3.1 Top 10 countries for volunteering time, by participation and population 22 2.3.2 Volunteering time and gender 23 2.3.3 Volunteering time and age 24 3 Continental comparisons 3.1 Continental World Giving Index scores 25 3.2 Continental giving behaviour scores 26 4 Most improved countries 4.1 Most improved countries for 2015 27 4.2 Most improved countries over time 28 Appendices 1 Alphabetical CAF World Giving Index full table 30 2 CAF World Giving Index full table 32 3 Helping a stranger full table 35 4 Donating money full table 37 5 Volunteering time full table 39 6 Methodology 41 7 Surveyed countries 42 Copyright © Charities Aid Foundation 2015 All rights reserved. -

Rules to Give By: a Global Philanthropy Legal Environment Index 3 Nexus | Mcdermott Will & Emery | Charities Aid Foundation Acknowledgements

Rules to Give By A Global Philanthropy Legal Environment Index Initiated by Nexus; legal research conducted by McDermott Will & Emery LLP; analysis provided by Charities Aid Foundation, Nexus and McDermott Will & Emery LLP. Written by Elaine Quick Toni Ann Kruse Adam Pickering Contents Acknowledgments 4 About the Partners 5 Forewords 6 Rules to Give By Index Map 8 Executive Summary 10 Scope and Limitations of the Study 12 Scoring the Rules to Give By Index 14 Questions and Scoring 14 Exempt Countries 14 Analysis 15 Findings 17 Rules to Give By Index 17 Analyzing Index Scores 25 Income Level 26 Regional Breakdown 28 Non-Profit Organizations 30 Tax Exemption 30 Reporting Requirements 30 Impact of Legal Structure on Giving 33 Tax Incentives 34 Effectiveness of Tax Incentives for Individuals 38 Different Incentives for Corporations and Individuals 40 Estate Taxes and Incentives for Legacy Donations 41 Rules to Give By Index in Alphabetical Order 43 Disclaimer 51 Rules to Give By: A Global Philanthropy Legal Environment Index 3 Nexus | McDermott Will & Emery | Charities Aid Foundation Acknowledgements Nexus would like to thank Alessandra Gregg, Clyde McConaghy, Elaine Quick, Yulya Spantchak, and Jonah Wittkamper. We are immensely grateful to McDermott Will & Emery LLP and the Charities Aid Foundation (“CAF”) for their dedication and the extensive resources they have committed to making this report possible. In particular we would like to thank Toni Ann Kruse, who led a team of over 70 attorneys at McDermott Will & Emery LLP in preparation of the Index to this report, and Adam Pickering at CAF, who led the analysis of the data compiled in the Index. -

The 2018 World Giving Index

CONTACT Kinga Ile Vice President, Thought Leadership & Communications CAF America Telephone: (202) 793 2232 www.CAFAmerica.org Angharad Thomas Charities Aid Foundation 0300 012 3286 The US is one of the world’s most consistently generous countries, according to leading global index of generosity The United States is one of the five most generous countries in the world, according to the CAF World Giving Index – the world’s leading measure of global generosity. Today’s report, which ranks 146 countries, put the US in 4th place worldwide, up one place from last year, and the most generous country in the region. This is the ninth World Giving Index report, in which the US has been in the top five every year – showing that the generosity of American people is consistent and strong. Around six in ten (61%) of people reported donating money in the month before they were polled, up from 56% last year. Almost three-quarters (72%) said they had helped a stranger in the past month. The survey also found that 39% of people had volunteered time. Levels of giving across Africa are continuing to grow, confirming a trend which appeared in last year’s Index. While last year’s report showed that every western country in the top 20 had a lower giving score, this decline has now largely been reversed. Indonesia tops the CAF World Giving Index for the first time. While its three individual giving scores are largely unchanged on last year, it has moved into the top spot. Polling was carried out in 2017, and so before the earthquake and tsunami which struck the country in September 2018. -

A Global Pandemic Special Report June 2021

CAF WORLD GIVING INDEX 2021 A global pandemic special report June 2021 www.cafonline.org Contents Foreword 3 About this report 4 Solidarity across the globe 5 Key Findings 6 The CAF World Giving Index 7 The world’s highest scoring countries 7 The world’s lowest scoring countries 8 Global Scores Over Time 10 Risers and Fallers 13 Helping a Stranger 14 Donating Money 15 Volunteering Time 16 Methodology 17 CAF World Giving Index full table 18 Copyright © Charities Aid Foundation 2021 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. foreword The results of this year’s Charities Aid Foundation At the Charities Aid Foundation, we have seen countless World Giving Index are, like the past year itself, truly moments of incredible generosity as our clients, both remarkable. The ravages of Covid-19 on charitable individuals and businesses, responded at pace to the giving around the globe are laid bare in the pages of this need on the ground around the world and I am proud report. Many of the countries that have been stalwarts of our unique expertise in cross-border giving that of our straight-forward gauge of global generosity over enabled us to send record amounts to some of the the past decade have fallen not just out of the top 10, most vulnerable communities on our shared planet. We but the top 20. -

CAF World Giving Index 2017

CAF W RLD GIVING INDEX 2017 A global view of giving trends September 2017 Registered charity number 268369 Contents Foreword 4 About this report 5 Key findings and conclusions 6 Laying the Groundwork for Growing Giving 7 CAF World Giving Index 2017 map 8 1 Global view 1.1 The CAF World Giving Index Top 20 10 1.2 Global trends across behaviours 13 2 Three giving behaviours 2.1 Helping a stranger 2.1.1 Top 10 countries for helping a stranger, by participation and population 16 2.1.2 Helping a stranger and gender 17 2.1.3 Helping a stranger and age 18 2.2 Donating money to charity 2.2.1 Top 10 countries for donating money, by participation and population 20 2.2.2 Donating money and gender 21 2.2.3 Donating money and age 22 2.3 Volunteering time 2.3.1 Top 10 countries for volunteering time, by participation and population 24 2.3.2 Volunteering time and gender 25 2.3.3 Volunteering time and age 26 3 Continental comparisons 3.1 Continental CAF World Giving Index scores 28 3.2 Continental giving behaviour scores 29 4 Most improved countries 4.1 Most improved countries for 2017 30 4.2 Most improved countries over time 31 Appendices 1 Alphabetical CAF World Giving Index full table 33 2 CAF World Giving Index full table 35 3 Helping a stranger full table 38 4 Donating money full table 40 5 Volunteering time full table 42 6 Methodology 44 7 Surveyed countries 45 Copyright © Charities Aid Foundation 2017 All rights reserved. -

Measuring the Environment for Philanthropy Across Countries: How Changing Political and Economic Landscapes Affect Charitable Giving

Measuring the Environment for Philanthropy across Countries: How Changing Political and Economic Landscapes Affect Charitable Giving Silvia Garcia ([email protected]) Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, Office of Community Engagement, Indianapolis, IN, U.S. Una Osili ([email protected]) Xiaonan Kou ([email protected], corresponding author) Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Indianapolis, IN, U.S. 1 Abstract While a complex array of economic, political, regulatory, and socio-cultural factors shape the development of philanthropy, the factors that support and enhance philanthropy’s growth are not well understood. Using data from the 2018 Global Philanthropy Environment Index, we explored how economic, political, and social factors operate to enable philanthropic activities. We examined the relationship between philanthropic environment for charitable giving and other contextual political, economic, and social factors. Results suggest that 1) formal giving is more likely to happen in countries with sounder tax incentives and favorable political and socio-cultural environments, while informal giving is exclusively connected to favorable socio-cultural conditions; 2) a country’s regulatory quality is a good predictor of its philanthropic environment; and 3) political, economic, and social factors may interact to reinforce each other in shaping the philanthropic environment, but such reinforcing interactions were mostly found in countries with very high levels of human development. Keywords: enabling environment, -

10Th Edition of the CAF World Giving Index We Are, for the First Time, Looking at the Lowest Scoring Countries on the Index

CAF WORLD GIVING INDEX1 0 T H E D I T I O N Ten years of giving trends October 2019 www.cafonline.org Contents Foreword 3 About this 10th edition report 4 Key findings 5 Laying the Groundwork for Growing Giving 6 The CAF World Giving Index 7 The world’s highest scoring countries over 10 years 7 The world’s lowest scoring countries over 10 years 8 The top 10 over time 9 Risers and Fallers 13 Helping a stranger 14 Donating money 16 Volunteering time 18 Giving behaviours for men and women 20 Giving behaviours across the generations 21 Method 22 CAF World Giving Index full table 23 Copyright © Charities Aid Foundation 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. foreword Welcome to this 10th anniversary special edition of CAF’s World Giving Index. We are once again very proud to produce the world’s largest survey of charitable endeavours from across the globe. That pride is not in celebration of our small part in telling this story, but rather in the generosity of people who give both their time and money to the people and causes that they care about. As this study now represents a full decade’s worth of data, we have taken a different tack this year in an effort to uncover longer term trends in giving and identify countries that are consistently among the biggest givers, along with those which are trailing behind.