The Review of Aboriginal Involvement in the Management of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wait-A-While Newsletter | Edition 11 December 2018

Mandingalbay Yidinji People Wait-a-While Newsletter | Edition 11 December 2018 From strength to strength INSIDE... Tribal Warrior SPECIAL FEATURE: New signs for training not all at Thinking Beyond GMYPBC sea...p 6 Borders...pages 13-19 ...p 22 A word from ED Dale Mundraby Welcome to our 2018 - one of our biggest years ever – Wait-a-While newsletter which I hope reflects on just some of the many things that have happened over the year, big and small, significant and seemingly less significant – although that’s never really the case, Executive Director (ED) Dale Mundraby writes... Our aspirations over many You will read about our new areas of expertise, from years, supported by our hard growing involvement and quarantine to coxswains. work and commitment, are engagement with the Yarrabah Everything we have done, coming to fruition at last. Council and community on even long before this great In the newsletter you several different levels from year, has been for a purpose will read about our first the GMYPPBC Master Plan of achieving our objectives Indigenous Protected Areas and signage project, the Social which are about improving and Economic Development Reinvestment Project, and the well-being of our People, Conference ‘Thinking Beyond even their school careers day Country and protection of Borders’ held in June this – we’re happy to contribute cultural natural values. year where we successfully and support these important And we are doing that by brought together many of community projects. developing and participating our stakeholders, supporters This year our organisation in the regional economy, and interested parties into has grown and developed creating a sustainable future one room to talk about how considerably, not only through hard work. -

Annual Report 2013 - 2014

Annual Report 2013 - 2014 Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network Ltd Ican Annual Report 2013 - 2014 Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network Ltd ABN: 62 127 786 092 PO Box 1108, North Cairns, QLD, 4870 Phone: 07 4031 1073 | Fax: 07 4031 5883 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ican.org.au ABOUT ICAN ICAN’s vision – Empowering Indigenous Consumers The Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network Ltd (ICAN) achieves its vision of Empowering Indigenous Consumers by providing financial counselling assistance to alleviate consumer detriment, education to make informed consumer choices and research/advocacy to highlight consumer disadvantage. ICAN’s values ‘Empowerment’ – ICAN believes that to create positive change, financial and consumer capability needs to be built within the Indigenous community and that there needs to be an emphasis on respecting Individual’s existing knowledge and culture in delivery. ‘Innovative’ – Striving to develop innovative long-term solutions built from the wants and needs of the communities we service. ‘Accountability’ – An organisation built on outcomes not rhetoric supported by a solid evidence base. ‘Partnership’ – A developed, integral understanding that collectively working with community, government and industry creates real change – positive relationships are key to moving forward. ‘Community’ – responsibility to the communities we service, recognition of the importance of family and a respect for the work life balance of our staff. Acknowledgement First and foremost, ICAN would like to respectively acknowledge the Traditional Owners of these Lands, Sea and Water, that we are privileged to walk, to engage, to work on and to work with. We would also like to sincerely pay respect to our past Traditional Owners, Elders, family and loved ones that are not with us today, but are in spirit. -

National Native Title Tribunal

NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 CONTENTS Letter to Attorney-General 1 Table of contents 3 Introduction – President’s Report 5 Tribunal values, mission, vision 9 Corporate overview – Registrar’s Report 10 Corporate goals Goal One: Increase community and stakeholder knowledge of the Tribunal and its processes. 19 Goal Two: Promote effective participation by parties involved in native title applications. 25 Goal Three: Promote practical and innovative resolution of native title applications. 30 Goal Four: Achieve recognition as an organisation that is committed to addressing the cultural and customary concerns of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 44 Goal Five: Manage the Tribunal’s human, financial, physical and information resources efficiently and effectively. 47 Goal Six: Manage the process for authorising future acts effectively. 53 Regional Overviews 59 Appendices Appendix I: Corporate Directory 82 Appendix II: Other Relevant Legislation 84 Appendix III: Publications and Papers 85 Appendix IV: Staffing 89 Appendix V: Consultants 91 Appendix VI: Freedom of Information 92 Appendix VII: Internal and External Scrutiny, Social Justice and Equity 94 Appendix VIII: Audit Report & Notes to the Financial Statements 97 Appendix IX: Glossary 119 Appendix X: Compliance index 123 Index 124 National Native Title Tribunal 3 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1324-9991 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes if an acknowledgment of the source is included. Such use must not be for the purposes of sale or commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without written permission. -

The Mandingalbay Yidinji People's Native Title Determination

Yidinji People. Yidinji and land remove to amended was application the 2004, October 8 On State and the laws of the Commonwealth apply to the Mandingalbay Mandingalbay the to apply Commonwealth the of laws the and State 1998. in lodged previously had they applications two of combination then the other interests will usually have priority. The laws of the the of laws The priority. have usually will interests other the then a was application This 1999. August 18 on Court Federal the with interests, other with odds at are interests and rights title native application title native their lodged People Yidinji Mandingalbay The have been recognised and protected in the determination. If the the If determination. the in protected and recognised been have accessing or using those reserves. The interests of the general public public general the of interests The reserves. those using or accessing map). (see hectares 3140 about cover areas and Malbon Thompson Forest Reserve does not stop other people people other stop not does Reserve Forest Thompson Malbon and ILUA and determination The Authority. Management Tropics Wet The recognition of native title over Grey Peaks National Park Park National Peaks Grey over title native of recognition The and Corporation Aboriginal Yidinji Mandingalbay the Queensland, of one another in these areas. These groups (the parties) were the State State the were parties) (the groups These areas. these in another one (State Parks and Forests Area Agreement). Area Forests and Parks (State alongside interests and rights their exercise will they how establishes It known as the Mandingalbay Yidinji Indigenous Land Use Agreement Agreement Use Land Indigenous Yidinji Mandingalbay the as known areas. -

Blak Roots, Held at Kickarts Contemporary Arts, Commemorating 20 Years of Wet Tropics World Heritage in Collaboration with School of Creative Arts, JCU

blah rootq Cover. RighI: Mark Hollingsworth, Bigin (rainforest shield) 2007 KickArts Contemporary Arts Board Of Directors Left Dawn Naranatjil, Yakuri (school of bait fish) 2007 (detail) Mike Fordham, Chair Back: Abe Muriata, Jawun. Lawyercane, 2007 Jenni Le Comle, Secretary Robyn Baker This catalogue celebrates a body of work collated for the KickArts Indig Jeneve Frizzo enous Survey exhibition, Bfak Roots, commemorating 20 Years of Wet Robin Maxwell Tropics World Heritage in collaboration with School of Creative Arts, Billy Missi JCU. Roland Nancarrow Andrew Prowse KickArts Contemporary Arts is a not-for-profit company limited by guar Gayleen Toll antee and is supported financially by Arts Queensland and the Australia Robert Will met Council for the Arts through the Visual Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, State and Te rritory Governments. KickArts Contemporary Arts Staff Rae O'Connell, Director Sponsors and Partners Beverley Mitchell, Shop Manager Arts Queensland Linda Stuart, Administration Manager Australia Council for the Arts Samantha Creyton, Curator Wet Tropics Management Authority Andrew Weatherill, Business Development Manager James Cook University, School of Creative Arts Jan Aird, Marketing Manager QantasUnk Leith Maguire, Administrator Boom Sherrin Morgan Brady, Administrator Black and Moore Pawsey and Prowse © KickArts Contemporary Arts 2008 Copyright KickArts Contemporary Arts, the artists and authors 2008. This Publisher work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright KickArts Contemporary Arts Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from 96 Abbott Street Cairns OLD 4870 Australia the publisher. No illustration in this publication may be reproduced without Postal address: PO Box 6090 Cairns QLD 4870 Australia the permission of the copyright owners. -

ICAN Annual Report 2009-2010

Annual Report 2009 Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network Ltd Ican Annual Report 2009 Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network Ltd ABN: 62 127 786 092 PO Box 1108, North Cairns, QLD, 4870 Phone: 07 40311073 | Fax: 07 40315883 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ican.org.au REPORTS: 02 ADVOCACY: 07 EDUCATION: 13 ASSISTANCE: 17 FINANCIAL: 24 CONTENTS REPORTS: 02 ADVOCACY: 07 EDUCATION: 13 ASSISTANCE: 17 FINANCIAL: 24 ICAN Annual Report 2009 | 1 CHAIRMAN’S Report In this our second year of view to improving financial health in the long term – and for a lifetime. operating as the Indigenous As a recently incorporated organisation with Consumer Assistance Network a newly appointed Board, strengthening Limited, ICAN has undergone corporate governance and the capacity of the Board has been a priority. As part of significant structural changes in meeting this priority, the Directors attended working to meet the needs of a half-day workshop designed to raise awareness of ICAN’s legal obligations Indigenous people in a changing and the Directors’ responsibilities. The economic environment. workshop included information on current legal issues and those on the horizon. To enable us to provide a further reaching The past year has been marked by major and more diverse service ICAN sought shifts in law and policy in areas such as funding from a wider range of sources. consumer law and fiscal concerns in remote ICAN was successful in gaining additional Indigenous communities. funding from both the public and private sectors which allowed employment of The national consumer law reform process, more Indigenous staff and assistance to which remains ongoing, has provided ICAN more Indigenous people – both important with an important opportunity to contribute achievements. -

ICAN Annual Report 2012-2013

Annual Report 2012 - 2013 Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network Ltd Ican Annual Report 2012 - 2013 Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network Ltd ABN: 62 127 786 092 PO Box 1108, North Cairns, QLD, 4870 Phone: 07 4031 1073 | Fax: 07 4031 5883 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ican.org.au REPORTS: 02 RESEARCH: 07 ADVOCACY: 09 EDUCATION: 13 ASSISTANCE: 19 FINANCIAL: 25 CONTENTS REPORTS: 02 RESEARCH: 07 ADVOCACY: 09 EDUCATION: 13 ASSISTANCE: 19 FINANCIAL: 25 ICAN Annual Report 2012 - 2013 | 1 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT As Chairman of the Indigenous received the “Highly Commended” Award in the “Community” Awards category, at the Consumer Assistance Network inaugural MoneySmart Week Awards, held in Sydney in early September 2012. I am Ltd, I am pleased to share with pleased to welcome the 11 new trainees to you the strategic directions of the the 2013 program, comprising 5 ICAN Staff members from Cairns and the Yarrabah organisation from the past financial Community, and 6 external students joining year and for our future. I wish to us from Derby (WA), Alice Springs (NT), Port reflect upon ICAN’s progress over Augusta (SA), Penrith (NSW) and Cairns. the past year in achieving our ICAN has taken significant steps towards sustainability of the organisation by working vision of Empowering Indigenous with Foresters Community Finance, a Consumers. Community Development Finance Institution (CDFI) to purchase property at 209 Buchan Street, Bungalow. This is a major investment into our organisation’s long term ICAN is leading the way in addressing sustainability and longevity in our service the under representation of qualified delivery. -

Speakers' Abstracts and Biographical Notes

The CLC has a proud history of Warrick Angus is the Manager of the unconventional gas development on their PEAKERS empowering traditional owners with Crocodile Islands Rangers. The Crocodile lands. In 2013 and 2014, in the absence of S ’ reliable knowledge around contentious Islands Rangers (CIR) manage the land a formal future acts process, the Yawuru issues. This paper discusses the and sea country of the Crocodile Islands PBC embarked on a process to inform multi-faceted approach being taken to - an area of international conservation and ascertain the position of the Yawuru ABSTRACTS AND enhance the professional knowledge of significance in remote north east Arnhem community on the proposed fracking. staff in unconventional oil and gas and Land in the Northern Territory. Warrick is The Yawuru PBC coordinated a to communicate in a balanced way to responsible for the overall coordination detailed assessment of the proposed BIOGRAPHICAL constituents the methods and risks of this and management of the CIR program, and fracking program, including engaging developing industry. since 2011 he has helped it to grow from independent experts to review the a handful of volunteers to a functional and Anthony Alexopoulos has an honours program, making submissions to NOTES successful nger program. degree in mining engineering and a government and developing maps of www.crocodileislandsrangers.org graduate diploma in mine ventilation. cultural values in the area. Several He has worked in the Queensland Leonard Bowaynu is an Executive community information meetings led to underground coal industry with experience Committee Member of the Crocodile a decision-making meeting in July 2014, ANTHONY in gas drainage and in the Western Islands Rangers. -

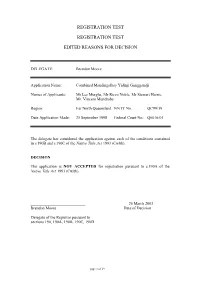

260303 Delegate's 190A Decision QC99 39 Edited

REGISTRATION TEST REGISTRATION TEST EDITED REASONS FOR DECISION DELEGATE: Brendon Moore Application Name: Combined Mandingalbay Yidinji Gunggandji Names of Applicants: Mr Les Murgha, Mr Ricco Noble, Mr Stewart Harris, Mr. Vincent Mundraby Region: Far North Queensland NNTT No.: QC99/39 Date Application Made: 25 September 1998 Federal Court No.: Q6016/01 The delegate has considered the application against each of the conditions contained in s.190B and s.190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). DECISION The application is NOT ACCEPTED for registration pursuant to s.190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). 26 March 2003 Brendon Moore Date of Decision Delegate of the Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D page 1 of 29 Information considered when making the Decision In making my decision pursuant to s. 190A I have considered and reviewed the application and all of the information and documents from the following files, databases and other sources: o The National Native Title Tribunal’s registration test and legal services files for this application Q6016/01 (Tribunal reference QC99/39), for the underlying applications QG6018/98 and QG6104/98 (QC98/40 & QC98/41) and for other applications that previously overlapped the area of this claim: § Mandingalbay Yidinji - QG6015/98 (QC99/40) (and the pre-combined Mandingalbay Yidinji claim QG6094/98 (QC96/88) § Combined Gunggandji - QG6014/98 & QG6005/98, now Q6013/01 (QC95/8 & QC94/8, now QC01/19) (including Form 1 applications, amended Form 1 applications, accompanying documents