Building a Spirit of Sustainability in Architectural Design by John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Goods Resource List

The American Wind Energy The Real Goods Resource List Association Although this Sourcebook is a complete source of renewable energy and envi- 1101 14th Street NW, 12th Floor ronmental products, we can’t be everything to everyone. Here is our current list Washington, DC 20005 of other trusted resources for information and products. We’ve selected these Website: www.awea.org/ organizations carefully, and since we have worked directly with many of them, Email: [email protected] we are giving you the benefit of our experience. Still, we’ll offer the standard Phone: 202-383-2500 disclaimer that Gaiam Real Goods does not necessarily endorse all the actions A national trade association of each group listed, nor are we responsible for what they say or do. that represents wind-power This list can never be complete. One good place to look for additional re- plant developers, wind turbine sources is www.wiserearth.org, an amazing compendium of tens of thousands of manufacturers, utilities, consultants, nonprofits compiled by Paul Hawken over many years (also see his bookBlessed insurers, financiers, researchers, and Unrest, p. 29). We apologize for resources we may have overlooked and for con- others involved in the wind industry. tact information that may have changed since this 30th-Anniversary Edition of These folks primarily work with utility- the Sourcebook went to press. We welcome your suggestions. Please mail a brief level wind systems. Not a good source description of the organization and access info to Gaiam Real Goods, Attention: for -

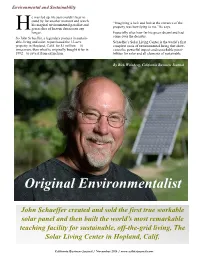

John Schaeffer

Environmental and Sustainability e was fed up. He just couldn‟t bear to stand by for another moment and watch “Imagining a lock and bolt at the entrance of the his magical environmental paradise and property was horrifying to me,” he says. H green slice of heaven deteriorate any longer. Especially after how far his green dreamland had come over the decades. So John Schaeffer, a legendary pioneer in sustain- able-living and solar, repurchased the 12-acre Schaeffer‟s Solar Living Center is the world‟s first property in Hopland, Calif. for $1 million – 10 complete oasis of environmental living that show- times more than what he originally bought it for in cases the powerful impact and remarkable possi- 1992 – to save it from extinction. bilities for solar and all elements of sustainable By Rick Weinberg, California Business Journal Original Environmentalist John Schaeffer created and sold the first true workable solar panel and then built the world’s most remarkable teaching facility for sustainable, off-the-grid living, The Solar Living Center in Hopland, Calif. California Business Journal / November 2016 / www.calbizjournal.com By Rick Wein- Environmental and Sustainability living practices with regal sculpture gardens, wa- terways, ponds, and an vast array of environmental While studying at UC Berkeley in the early 1970s, products for people wanting to live off the grid or Schaeffer became more and more intrigued with just „green up‟ their lives. The breathtaking park the environment and the most simplistic form of draws more than 200,000 visitors annually. basic living. When he participated in the first Earth “There are not enough words in any language to Day in 1970, his life‟s mission and purpose was convey what an impact John Schaeffer has had on solidified – “I knew this is what I was born to do,” solar, the environment and sustainable living,” he says. -

Sustainable Living

The Joys of Sustainable Living With Udgar Parsons, Owner & Founder of Growing Spaces LLC SUSTAINABLE LIVING There are many changes facing us as a species at this time. Among these are overpopulation, resource depletion, climate change, aquifer contamination and depletion, species extinction, deforestation. The list is much longer, but I am going to focus on three: climate change, resource depletion and control of our political system by corporate and financial interests. GLOBAL WARMING Scientist James Hansen was one of the first to publicly announce the danger of manmade global warming via the increase in greenhouse gases due to increase in CO2 levels in the atmosphere. Despite a huge PR effort by the climate change deniers, the public is gradually accepting that global warming is a fact, not a debate. Melting of the two polar ice caps, the huge retreat of the worlds’ glaciers, acidification and warming of the ocean, loss of species, noticeable changes in temperature records, and increase in El Niño events, droughts and floods have all been predicted and are occurring. The fossil fuel companies have a huge responsibility to shoulder, as their continued efforts to deny and influence legislation continue to lead us down a path that has significant and terrible consequences for humanity and all of life on our planet. RESOURCES Game Over for the Climate: The science of the situation is clear — it’s time for the politics to follow by James Hansen https://www.commondreams.org/view/2012/05/10-2 Dr. James Hansen is director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and adjunct professor in the department of earth and environmental sciences at Columbia University. -

York's Wild Kingdom: a Development Proposal by Kimberley Whiting Rae

York’s Wild Kingdom: A Development Proposal by Kimberley Whiting Rae B.A., Fine Arts 1991 Colgate University Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 2008 ©2008 Kimberley Whiting Rae All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author_________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning July31, 2008 Certified by_______________________________________________________________ Dennis Frenchman Leventhal Professor of Urban Design and Planning Director, City Design and Development Accepted by______________________________________________________________ Brian A. Ciochetti Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development 2 York’s Wild Kingdom: A Development Proposal by Kimberley Whiting Rae B.A., Fine Arts 1991 Colgate University Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development ABSTRACT York’s Wild Kingdom is a privately held zoo and amusement park in York, Maine. Berkshire Development, a Massachusetts based shopping center developer and investment company currently controls the Wild Kingdom and the 150 acres that surround it. The community is culturally divided between York Harbor and York Beach, which is relevant to the entitlement process. The site is uniquely positioned to provide a new public road to York Beach directly from the highway, thus alleviating a longstanding traffic congestion problem for York Harbor. -

Architecture Program Report for Initial Accreditation: APR-IA Professional Master of Architecture Submitted to the National Architectural Accrediting Board April 2013

The University Of Arizona School of Architecture Architecture Program Report for Initial Accreditation: APR-IA Professional Master of Architecture Submitted to the National Architectural Accrediting Board April 2013 Kathleen Landeen Robert Miller Andrew C. Comrie Ann Weaver Hart Graduate Coordinator Director Senior Vice President for President School of Architecture School of Architecture Academic Affairs & Provost University of Arizona University of Arizona 1040 North Olive Road 1040 North Olive Road 1401 E. University Blvd. Tucson AZ 85721 Tucson AZ 85721 1401 E. University Blvd. Administration Building 712 Administration Building 512 Tucson, Arizona 85721 [email protected] [email protected] Tucson, Arizona 85721 520.621.9819 520.626.6752 520.621.5511 [email protected] Christopher Domin 520.621.1856 Associate Professor Program Chair M.Arch program 1040 North Olive Road Tucson AZ 85721 [email protected] 520.891.8859 ABOR ....................................................................................... Arizona Board of Regents ACSA .........................................Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture AIA ...............................................................................American Institute of Architects BSSBE ..............................Bachelor of Science in Sustainable Built Environments CAPLA .........The College of Architecture, Planning +Landscape Architecture DDBC ...................................................................... Drachman Design-Build Coalition -

Arch 750 Tectonics Pages Final.Indd

Form and Force an exploration of tectonics contributing authors: george aguilar ashley brunton matthew dickman giuliana fustagno eddie garcia jason jirele ashton mcwhorter alycia pappan dipen patel alexandra wilson jessica wyatt Form and Force An Exploration of Tectonics Authors George Aguilar Ashley Brunton Matthew Dickman Giuliana Fustagno Eddie Garcia Jason Jirele Ashton Mcwhorter Alycia Pappan Dipen Patel Alexandra Wilson Jessica Wyatt Special Thanks To Chad Schwartz Additonal Contributions: Book Layout and Coordination Dipen Patel Ashley Brunton Matthew Dickman Cover Design and Coordination Jason Jirele Eddie Garcia Project Map and References Ashton McWhorter Giuliana Fustagno Project Credits and Figure Credits Jessica Wyatt George Aguilar ©2017 Department of Architecture, College of Architecture, Planning & Design, Kansas State University All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, or utilized in any form or by any means without written permission of the copyright owners. This book is not for resale and may not be distributed without consent by the Department of Architecture at Kansas State University or its representatives. All of the photographs and other images in this document were created by the authors – the students in ARCH 750 Investigating Architectural Tectonics, Fall 2017 – unless otherwise noted. Every effort has been made to ensure that credits accurately comply with information supplied. Table of Contents Preface v Alycia Pappan Acknowledgments vii Project Map ix 01 Agosta House | Patkau -

Architectsnewspaper 16^10.5.2004

THE ARCHITECTSNEWSPAPER 16^10.5.2004 NEW YORK ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN WWW.ARCHPAPER.COM $3.95 OPPONENTS' PETITION TO C/) HALT CITY REVIEW PROCESS 04 DENIED DESIGN SAVES LU AIA-NY ANNOUNCES I- DEMOCRACIES HUDSON O 05 4 AWARD WINNERS o YARDS STILL COPYCAT CAUGHT 08 ON TRACK WHALES,BEETLES, ETC., AT THE The Hudson Yards Development Plan went forward with a public hearing on VENICE BIENNALE Thursday, September 23, after a judge Tl ruled against a group of Far West Side residents and businesses that sued the HOLY BATTLE, city and Metropolitan Transit Authority to SACRED GROUND halt review of the project. The suit, filed in Daiki Theme Park by Ga. A Architects, the State Supreme Court in Manhattan on 03 EAVESDROP Mass Studies, and Cho/Slade Architecture August 26, centered on the Draft Generic 15 CLASSIFIEDS Environmental Impact continued on page 3 On September 20, the New York chapter of projects for non- profits," she commented. the AIA announced the winners of its annual "It is very challenging to do, and these proj• design awards. After a long day of poring ects were handled well." Their admiration STATEN ISLAhI D DEDICATE^^ Sono, an architect at Voorsanger & was not limited to work done for under over almost 400 submissions, which are 9/11 AjEMOR] Associates Architects in Manhattan, restricted to AIA New York members or New $200 per square foot. After Joy presented arrived at his concept serendipitously. As York State-licensed architects practicing in Peter Gluck's Scholar's Library, a tiny box in part of his routine design process, he uses New York City, jurors presented their winning the woods in upstate New York for a private postcards to build parti models. -

Recycling at Work. Successes

Table of Contents Award Winners The DMA Robert Rodale Recycler of the Year Warner Bros. Studios Facilities (Honorable Mention) Quad/Graphics The DMA Robert Rodale Environmental Mailer of the Year Real Goods Trading Company Model Recycler Leanne Meyer, Recycling Coordinator, United States Postal Service of Lansing, Michigan Buy Recycled General Services Agency of Alameda County, California Clean Your Files Day State of Iowa, Departments of General Services and Natural Resources Closed Loop Recycling United States Postal Service Commercial Recyciing Programs City of Allentown, Pennsylvania Employee Education and Outreach City of Los Angeles, California Environmental Responsibility United States Postal Service Improved Recycling Rates Canon U.S.A., Inc. Public Outreach City of Burbank, California City of Louisville, Kentucky Award Applicants AlliedSignal Boise Cascade St. Helens’ Paper Mill Bowie State University, ARAhMRK Campus Services Chevron Real Estate Management Company City of Allentown, Pennsylvania City of Bloomington, Indiana City of Fountain Valley, California City of Irving, Texas City of San Jose, California City of Visalia, California Horizon Air Towson University, ARAMARK Campus Services United States Postal Service Introduction ~~ ~ The National Ofice Paper Recycling The Recycling at Work Awards were There is something to be learned from Project has evolved since its founding designed to not only recognize the govern- every recycling program highlighted in this in 1990 to reflect a new emphasis, the ment entities, organizations and businesses publication. From motivational public out- Recycling at Work Campaign. As the whose leadership has ensured the success of reach campaigns to fruithl Clean Your Files program has grown to encompass new workplace recycling nationwide, but also to Day programs, all demonstrate the dedica- workplace recycling issues, so have the highlight these achievements as inspiration tion, cooperation and creativity that com- Annual Recycling at Work Awards grown for others. -

Introduction Section 2: Principles of Natural Systems and Design

Section 1: Introduction Permaculture Ethics: “Care of the Earth” ― includes all living and non-living things, such as animals, plants, land, water, and air. “Care of People” ― promotes self-reliance and community responsibility. “Give Away Surplus” ― pass on anything surplus to our needs (labor, money, information) for the above aims. Implicit in the above is the “Life Ethic”: all living organisms are not only means but ends. In addition to their instrumental value to humans and other living organisms, they have an intrinsic worth. Permaculture is an ethical system, stressing positivism and cooperation. Section 2: Principles of Natural Systems and Design Guiding principles of permaculture design: • Everything is connected to everything else • Every function is supported by many elements • Every element should serve many functions What is design? It is composed of two elements: aesthetics and function. Permaculture design concen- trates on function . Functional design is: 1. Sustainable ― it provides for its own needs 2. Provides good product yield, or even surplus yield. This happens when elements have no prod- uct unused by other elements, and they have their own needs supplied by other elements in the system. If these criteria are not met, then pollution and work result. Pollution is a product not used by some- thing else; it is an over -abundance of a resource. Work results when there is a deficiency of resources and when an element in the system does not aid another element. Any system will become chaotic if it receives more resources then it can productively use (e.g. too much fertilizer can result in pollution). -

Susannah Dickinson Curriculum Vitae

SUSANNAH DICKINSON CURRICULUM VITAE CHRONOLOGY OF EDUCATION, PROFESSIONAL REGISTRATION EDUCATION 2015 - present European Graduate School, EGS, Saas-Fee, Switzerland PhD Candidate in Architecture and Urbanism Seminar Faculty: Philip Beesley, Benjamin H. Bratton, Mladen Dolar, Keller Easterling, Christopher Fynsk, Geert Lovink, Sanford Kwinter, Neil Leach, Casey Reas, François Roche, Slavoj Zizek and Alenka Zupancic. 1996 - 1998 California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, California, USA Master of Architecture; Thesis: Technology and Nature, Chair: Hsinming Fung 1988 - 1989 University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, USA Architecture Study Abroad Program, (awarded through the University of Liverpool, England) 1984 - 1987 University of Liverpool, Liverpool, England Bachelor of Arts in Architecture (with honors) PROFESSIONAL REGISTRATION 2008 - present National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) Certification granted through completion of qualifying education, Intern Development Program (IDP) and all divisions of the Architect Registration Examination (ARE); Certificate #65022 2016 - present License to Practice Architecture, State of Arizona Through NCARB Certificate, Registration#63200 2008 - 2016 License to Practice Architecture, State of New York Through NCARB Certificate, Registration#032822 2006 - 2015 License to Practice Architecture, State of California Through qualifying education, ARE exams and oral examination, Registration #30648 CHRONOLOGY OF ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2009 - present School of Architecture, University -

Real Goods & Quattro Solar Announce Strategic Partnership To

For more information, please contact: John Schaeffer/Real Goods 707.472.2401 ([email protected]) Real Goods & Quattro Solar Announce Strategic Partnership to Provide Solar PV Hopland, California – November 21, 2016 – Real Goods Trading Corporation together with Quattro Solar, Inc. of Novato, CA, announced today the formation of a strategic partnership to jointly provide grid-tied and off- grid solar PV design, installation, administrative, and maintenance services to homes and businesses in Northern California. Real Goods sold the very first PV solar panel nearly 40 years ago in 1978 and has been recognized as the pioneer in solar with more experience than any other company in Northern California. Quattro Solar, Inc. was founded in 2010 in Novato, California and has been specializing in residential and small commercial solar installations. Quattro has done solar installations on over 300 homes, wineries, and small businesses, between the San Francisco Bay Area, north of Willits, as far east as the Sacramento Valley, and as far South as Santa Cruz. Real Goods will provide the equipment for each solar installation including the PV modules, power inverter, racking, balance of systems components, and storage batteries for off-grid independent systems. Quattro will be providing administrative services including design, building permit and utility submissions, inspections, and tax credit information for the homeowner or small business. Real Goods owner and founder, John Schaeffer, commented: “We’re very excited to be working with Quattro Solar to be able to close the loop with our customers by offering turn key solar systems. For years we’ve specialized in independent off-grid systems and now we can serve ALL of our grid tied residential customers and small businesses with a complete solar package.” David Quattro, President and founder of Quattro Solar added: “It’s a long standing dream of ours to be working with Real Goods as their solar installation arm. -

REAL GOODS Off-Grid Living Since 1978

REAL GOODS www.realgoods.com off-grid living since 1978 FALL 2015 Visit Our Solar Living Center and Store to See our Products Come Alive! SOLAR POWER Off-grid specialists Real Goods HOMESTEADING Everyday solutions is the GARDEN & COMPOSTING original Tried and true goods CAMPING AND solar PORTABLE POWER Solar gadgets and gear company! More than 200 WE’RE BACK! earth-friendly Our First tools to power Catalog off-grid in 4 years! lifestyles don’t see it here? or want to Order? Call us. 800.919.2400 Welcome to Our First Real Goods Catalog Since 2011! What a wild ride this The Real Goods Solar Living Sourcebook, 14th edition solar-coaster has been “…the best single source I’ve ever found on the technologies, philosophies and the since we sold the first lifestyle changes we must embrace in order for our species to survive and thrive solar panel in the U.S. in into the future.” —Woody Harrelson, environmentalist, actor 1978. From our humble beginnings in my garage “…an owner’s manual for regenerating our earth, skies and water… a master- we grew over the next 20 work on re-inhabitation… the best manual you could possibly want.” years to six retail loca- —Paul Hawken, Project Drawdown, author Blessed Unrest tions and two national Solar Living Sourcebook retail catalogs. In the “…I have always recommended the as the #1 source, early 2000s our focus indeed the Bible, for all things solar and sustainable. shifted to turnkey rooftop John (right) & Poppy surveying Bravo to the 14th edition, it’s the best one yet!” the SunHawk Farms olive orchard environmentalist, actor solar, we went public in —Ed Begley Jr., (see p.