Collaborative Forest Management in Victoria's Wombat State Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Report on a Community Partnership in Eco-Acoustic Monitoring in Brisbane Ranges National Park, Victoria

Australian Owlet-nightjar. Photo: Damian Kelly A REPORT ON A COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP IN ECO-ACOUSTIC MONITORING IN BRISBANE RANGES NATIONAL PARK, VICTORIA Prepared by: Dr Sera Blair, Christine Connelly, Caitlin Griffith, Victorian National Parks Association. Dr Karen Rowe & Dr Amy Adams, Museums Victoria Victorian National Parks Association The Victorian National Parks Association (VNPA) helps to shape the agenda for creating and managing national parks, conservation reserves and other important natural areas across land and sea. We work with all levels of government, the scientific community and the general community to achieve long term, best practice environmental outcomes. The VNPA is also Victoria’s largest bush walking club and provides a range of information, education and activity programs to encourage Victorians to get active for nature. NatureWatch NatureWatch is a citizen science program which engages the community in collecting scientific data on Victorian native plants and animals. The program builds links between community members, scientists and land managers to develop scientific, practical projects that contribute to a better understanding of species and ecosystems, and contributes to improved management of natural areas. Project Partners Museums Victoria Museums Victoria has been trusted with the collection and curation of Victoria’s natural history for over 160 years and serves as a key international research institute and experts in data archiving and long- term data protection. Responding to changing intellectual issues, studying subjects of relevance to the community, providing training and professional development, and working closely with schools, communities, and online visitors, Museums Victoria works to disseminate our collective knowledge through online resources and image, audio and video databases. -

Australia's Ildlife Onders

GREAT SOUTHERN TOURING ROUTE AUSTRALIA’S AUSTRALIA ILDLIFE ONDERS VICTORIA www.greatsoutherntouring.com.au BOTANICA WORLD DISCOVERIES For those seeking a specialist garden tour along the Great Southern Touring Route or other Australian destinations we recommend Botanica World Discoveries. The Victorian Homesteads, Gardens and Mansions tour follows the Great Southern Touring Route and provides special access to gardens that will inspire and delight those with ‘green thumbs and the love of gardens.’ www.botanica.travel MEET THE ARTIST Australia’s Great Southern Touring Route is widely regarded as the ‘journey of a lifetime’. This road trip captures the essence of Australia particularly the wildlife encounters to be experienced along the way. In a unique partnership between Great Southern Touring Route and Willie Wildlife Sculptures the amazing wildlife and dramatic landscapes are paired together and presented as joint heroes. Will Wilson’s sculptures of our wondrous native animals and birds inspire the traveller to explore and there is no better place to do this than the Great Southern Touring Route. From coastal cliffs, pristine beaches to ancient rainforests and mountain ranges the diverse protected landscapes of the Great Southern Touring Route are not only spectacular but also the home of a dazzling variety of birds, sea creatures and native animals. The skilful hands of Will Wilson captures the shape and form of these Australian native animals but also give an insight into their personality and character. Willie Wildlife Sculpture gallery is located in The Hive Ocean Grove on the Bellarine Peninsula. This guide is a celebration of art and wildlife as nature unfolds at every turn along this iconic Aussie road trip. -

Greater Glider Management Plan: South Gippsland. Draft

1 Greater Glider Management Plan: South Gippsland. Draft Greater Glider, Mirboo Regional Park (HVP). Powerful Owls, Mirboo Regional Park (Dickies Hill). 2 INDEX 1. Aim……………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………. 2. Biology………………………………………………………………………………….……………………….. 3. Current Distribution South Gippsland…………………………………………………………….. P.2 4. Greater Glider Populations…………………………………………………....……………………... P.2 4.1. Mirboo Regional Park & Dickies Hill……………………………..…………………………..…. P.2 4.2. Hallston…………………………………………………………………………………………………….…. P.3 4.3. Gunyah rainforest Reserve……………………………………………................................ P.3 5. Threats……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…. P.3 5.1. Habitat Connectivity…………………………………………………..……………………………..… P.4 5.2. Habitat Destruction…………………………………………………………………………………..... P.5 5.3. Predators…………………………………………………………….………………………………….…... P.5 5.4. Climate Change………………………………………………………………………………………….... P.5 5.5. Firewood Collection………………………………………………………………………………….….. P.5 5.6. Timber Production…………………………………………………………………………………..…... P.6 5.7. Other Threats………………………………………………………………….……………………….….. P.6 P.6 6. Management Actions…………………………………………………………………………. P.6 5.1 Current and Future Habitat Restoration …………………………………………………………….… P.7 Hallston……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… P.8 Mirboo RP…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. P.8 5.2 Genetic diversity……………………………………………………………………………………………….... P.10 5.3 Predation………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….. P.13 5.4 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………………………..………. P.14 -

Newsletter Welcome to Our Summer Edition

Issue 34 - December 2015 Newsletter Welcome to our summer edition. It is a time for insects; dragonflies, damselflies and butterflies all appreciate the warmer weather. Insects provide food for the many bird species that migrate to the Wombat Forest to breed. Beautiful mauve fringe lilies are starting to appear. It is also a time to look for sun orchids, and in the swampy areas, the large sickle greenhood orchids. Gayle Osborne (editor) and Angela Halpin (design) Owl Watch - Powerful Owls South of Trentham By Trevor Speirs In December last year, when searching for Rose Robins delight two Powerful Owls Ninox strenua were found and Pink Robins, Gayle and I stopped at a well-treed roosting in a Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon along the gully south of Trentham. No robins, but to our great dry creek bed. They appeared young, being slight in build and lightish in colour, and were a bit nervous, quickly taking off into the forest, but judging by the amount of familiar chalky excreta and small animal bones on the ground, this roost had been in use for some time. The surrounding bush looked like good owl habitat, with a stand of large Mountain Grey Gums Eucalyptus cypellocarpa with spacious hollows, and we made a note to return during next year’s breeding season. We visited on and off over the winter months, and while there was still plenty of evidence of owl presence, it was not until mid-September that we saw our first bird, a female. This was a good day, as shortly after dusk an owlet could be heard trilling from one of the grey gums that we suspected was being used for breeding. -

Project Atlas’, a Coal Seam Gas Field in the Surat Basin

7 — APPENDICES Appendix C – ERM Ecological Assessment Report Public—24 October 2018 © Jemena Limited Atlas Lateral Project Gas Compression Facility Ecological Assessment Report 0461545_FINAL September 2018 The business of sustainability Atlas Lateral Project Approved by: Dr David Dique Gas Compression Facility Ecological Assessment Report Position: Partner Senex Energy Limited Signed: September 2018 0461545 FINAL Date: 21 September 2018 www.erm.com This disclaimer, together with any limitations specified in the report, apply to use of this report. This report was prepared in accordance with the contracted scope of services for the specific purpose stated and subject to the applicable cost, time and other constraints. In preparing this report, ERM relied on: (a) client/third party information which was not verified by ERM except to the extent required by the scope of services, and ERM does not accept responsibility for omissions or inaccuracies in the client/third party information; and (b) information taken at or under the particular times and conditions specified, and ERM does not accept responsibility for any subsequent changes. This report has been prepared solely for use by, and is confidential to, the client and ERM accepts no responsibility for its use by other persons. This report is subject to copyright protection and the copyright owner reserves its rights. This report does not constitute legal advice. CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 2 1.2 SCOPE OF THE ASSESSMENT 2 2 RELEVANT LEGISLATION 5 3 ASSESSMENT APPROACH -

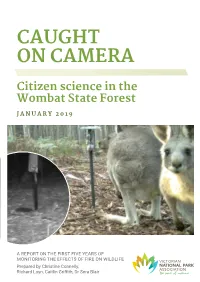

Caught on Camera

CAUGHT ON CAMERA Citizen science in the Wombat State Forest JANUARY 2019 A REPORT ON THE FIRST FIVE YEARS OF MONITORING THE EFFECTS OF FIRE ON WILDLIFE Prepared by Christine Connelly, Richard Loyn, Caitlin Griffith, Dr Sera Blair Victorian National Parks Association The Victorian National Parks Association is a community-led nature conservation organisation. Our vision is to ensure Victoria is a place with a diverse and healthy natural environment that is protected, respected and enjoyed by all. We work with all levels of government, the scientific community and the general community to achieve long term, best practice environmental outcomes and help shape the agenda for creating and managing national parks, conservation reserves and other important natural areas across land and sea in Victoria. We are also Victoria’s largest bushwalking club and provide a range of education, citizen science and activity programs that encourage Victorians to get active for nature. NatureWatch The Victorian National Parks Association’s NatureWatch program is a citizen science program which gets community involved in collecting scientific data on Victorian native plants and animals. The program builds links between community members, scientists and land managers and develops scientifically based, practical projects which contribute to a better understanding of species and ecosystems, and the management of natural areas. Project Partners Wombat Forestcare Wombat Forestcare is a community group dedicated to protecting and enhancing the natural ecosystems of the Wombat State Forest and surrounding areas. Eco Insights Eco Insights is a consultancy established by Richard Loyn that conducts strategic projects in Australia and Papua New Guinea. Richard is an ecologist with special interests in forests, fire, wetlands, threatened species, bird migration and conservation. -

Wombat Forest: a Greater Refuge for Gliders

Victorian National Parks Association An independent, non-profit, membership-based group, VNPA exists to protect Victoria’s unique natural environment and biodiversity through the establishment and effective management of national parks, including marine national parks, conservation reserves and other measures. VNPA works by facilitating strategic campaigns and education programs, developing policies, conducting hands-on conservation work, and by running bushwalking and outdoor activity programs which promote the care and enjoyment of Victoria’s natural heritage. Wombat Forestcare Inc. Wombat Forestcare Inc. is dedicated to preserving the biodiversity and amenity of the Wombat State Forest, Central Victoria, Australia, by utilising the skills and resources of the community. Wombat Forestcare engages in a range of activities. These have a strong focus on community involvement and education, and include undertaking flora and fauna surveys. We also enjoy the social aspect of a forest group, with picnics and bushwalks for people who love being in the bush. © Published by the Victorian National Parks Association & Wombat Forestcare Inc. February 2020. Licensed CC BY 3.0 AU http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/au/ Acknowledgements The analysis and preparation of Wombat Forest: A Greater Refuge for Gliders. Significance of Wombat Forests Greater Gliders (2020) was undertaken by Blake Nisbet and Conor Logan for the VNPA and Wombat Forestcare Inc. Gayle Osborne for her help and guidance in the preparation of the report. Wombat Forestcare volunteers for the use of Greater Gliders survey data. Jessie Borrelle for the design and layout of the report. Traditional Owners The Victorian National Parks Association acknowledges the many Traditional Owners of Victoria’s natural areas. -

Melbourne Bushwalkers Inc

THE NEWS OF THE A000133X Melbourne Bushwalkers Inc. ABN 14 396 912 508 August 2015 President’s Corner – August 2015 Jean Giese and her able assistant, Alister Rowe, have stepped down as Co-ordinators for the MOFs and TOFs Walks. ‘Jean who?’ I can hear many newer members ask. This is hardly a surprising reaction for a club as large as Melbourne Bushwalkers where member involvement can be focussed around a particular type or time of activity. But far from being a weakness it is a testament to the strength of several of our core values, namely those of providing a diversity of bushwalking and related activities and of inclusiveness. Put another way, if there is an activity you would like to see on the program and you are prepared to take a lead in its organisation then we will do what we can to help make it happen. It is what makes our club strong. In doing so it is accepted that any member with the capacity to participate will have the opportunity to participate. We provide each other the opportunity to try something different when we are ready. Jean very much embodies these values. Always an engaged member, and a Past President to boot, Jean rolled with the years and took the initiative to ensure that her advancing age would not exclude her from involvement in club trips. And so were ‘born’ Wednesday Walks, Monday Old Fogies (MOFs) Walks, Thursday Old Fogies (TOFs) Walks and Thursday Social Walks. Despite their names and the connotations they carry these walks are open to all members looking for good companionship and a walk to suit their schedule. -

The Student's Elements of Geology

The Student's Elements of Geology Sir Charles Lyell The Student's Elements of Geology Table of Contents The Student's Elements of Geology.........................................................................................................................1 Sir Charles Lyell............................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................2 CHAPTER I. ON THE DIFFERENT CLASSES OF ROCKS.....................................................................2 CHAPTER II. AQUEOUS ROCKS. THEIR COMPOSITION AND FORMS OF STRATIFICATION......................................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III. ARRANGEMENT OF FOSSILS IN STRATA. FRESH−WATER AND MARINE FOSSILS.....................................................................................................................................................14 CHAPTER IV. CONSOLIDATION OF STRATA AND PETRIFACTION OF FOSSILS.......................21 CHAPTER V. ELEVATION OF STRATA ABOVE THE SEA. HORIZONTAL AND INCLINED STRATIFICATION....................................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. DENUDATION..................................................................................................................40 -

Australia's Biodiversity – Responses to Fire

AUSTRALIA’S BIODIVERSITY – RESPONSES TO FIRE Plants, birds and invertebrates A.M. Gill, J.C.Z. Woinarski, A. York Biodiversity Technical Paper, No. 1 Cover photograph credits Group of 3 small photos, front cover: • Cockatiel. The Cockatiel is one of a group of highly mobile birds which track resource-rich areas. These areas fluctuate across broad landscapes in response to local rainfall or fire events. Large flocks may congregate on recently-burnt areas. /Michael Seyfort © Nature Focus • Fern regeneration post-fire, Clyde Mountain, NSW, 1988. /A. Malcolm Gill • These bull ants (Myrmecia gulosa) are large ants which generally build small mounds and prefer open areas in which to forage for food. They are found on frequently burnt sites. Despite their fierce appearance, they feed mainly on plant products. /Alan York. Small photo, lower right, front cover: • Fuel reduction burning in dry forest. This burn is towards the “hotter” end of the desirable range. /Alan York Large photo on spine: • Forest fire, Kapalga, NT, 1990. /Malcolm Gill Small photo, back cover: • Cycad response after fire near Darwin, NT. /Malcolm Gill ISBN 0 642 21422 0 Published by the Department of the Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia, 1999 Information presented in this document may be copied for personal use or pub- lished for educational purposes, provided that any extracts are acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department, or of the Commonwealth of Australia. Biodiversity Convention and Strategy Section Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 636 CANBERRA ACT 2601 General enquiries, telephone 1800 803772 Design: Design One Solutions, Canberra Printing: Goanna Print, Canberra Printed in Australia on recycled Australian paper AUSTRALIA’S BIODIVERSITY – RESPONSES TO FIRE Plants, birds and invertebrates A. -

Werribee River Ecohydraulics

Full Paper Parvin Zavarei, Christine Lauchlan Arrowsmith, Yafei Zhu Werribee River Ecohydraulics 1 2 3 Parvin Zavarei , Christine Lauchlan Arrowsmith and Yafei Zhu 1 Water Technology, 15 Business Park Drive, Notting Hill, Victoria, Australia, 3168. Email: [email protected] 2. Water Technology, 15 Business Park Drive, Notting Hill, Victoria, Australia, 3168. Email: [email protected] 3. Water Technology, 15 Business Park Drive, Notting Hill, Victoria, Australia, 3168. Email: [email protected] Key Points • Fine scale water quality modelling for water way health • Using of flushing flows for managing algal blooms • Integrating data collection, numerical modelling and interpretational analysis Abstract Agriculture is the dominant land use in the Werribee River catchment. Flow regime of the river has been dramatically altered to provide water for drinking and irrigation in this area, resulting in a significant depletion of flows in the lower reaches of the river in recent years. As a result, this area is affected by large- scale accumulation of floating weeds and blue-green algal (BGA) blooms. The best approach to manage this problem is to prevent their build up by supplying a large enough flow. This study assessed the performance of a set of environmental flow releases as the mitigation measure for this ongoing issue. A 2D and 3D hydrodynamic (HD) and advection-dispersion (AD) model of the lower Werribee river, was developed using MIKE by DHI 2D and 3D FM models. Hydraulic control points along the river were identified during a field survey. A series of ADCP velocity profiles were collected across the river by Water Technology during 2 environmental flow release events. -

Statement of Planning Policy © the State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2018

Macedon Ranges Statement of Planning Policy © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-1-76047-931-2 (Print) ISBN 978-1-76047-932-9 (pdf/online) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone DELWP Customer Service Centre 136 186, email [email protected], via the National Relay Service on 133 677 www.relayservice.com.au . This document is also available in Portable Document Format at www. delwp.vic.gov.au/planning Contents Foreword 2 Introduction 6 Purpose of the statement 6 Distinctive area and landscape declaration and policy approval 7 Using the statement 7 How the statement was prepared 8 Our vision 11 Framework plan 14 Policy domains 17 Landscape 17 Biodiversity and environmental values 19 Water catchments and supply 21 Aboriginal culture, heritage and caring for Country 23 Post-Contact cultural heritage 25 Agriculture and natural resources 26 Tourism and recreation 27 Settlements 28 Transport and infrastructure 31 Risks and resilience 32 Settlement boundary maps 34 Implementation 39 Monitoring and review 39 References 40 Glossary of terms 42 Foreword Included in final SPP.