Canadian Senate Reform: Recent Developments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fostering a Canadian Ecosystem for Systems Change

10 Years 10 Social Innovation Generation Fostering a Canadian Ecosystem for Systems Change Geraldine Cahill & Kelsey Spitz Foreword by David Johnston, Governor General of Canada 2 Social Innovation Generation Fostering a Canadian Ecosystem for Systems Change Geraldine Cahill & Kelsey Spitz Foreword by David Johnston, Governor General of Canada Social Innovation Generation Fostering a Canadian Ecosystem for Systems Change By Geraldine Cahill and Kelsey Spitz Edited by Nancy Truman www.thesigstory.ca Book design by Studio Jaywall in collaboration with Adjacent Possibilities Published by The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation Suite 1800, 1002 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, QC H3A 3L6 On the web: www.mcconnellfoundation.ca Please send errors to: [email protected] Licensed under Creative Commons, 2017 Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) Social Innovation Generation (SiG) Please feel free to circulate excerpts of Social Innovation Generation for noncommercial purposes. We appreciate acknowledgment where appropriate. First published in Canada by Social Innovation Generation, a platform founded and co-created by The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation. Printed in Canada by Flash Reproductions ISBN 978-1-7751318-0-9 Library and Archives Canada For Brenda Thank you for illuminating the paths we walk. In a complex world, you are our guide. For Katharine You uncovered critical insights from McConnell’s collaborations with its many partners and contributed to and nurtured the systems thinking that led directly to SiG’s creation. Foreword By David Johnston, Governor General of Canada One of the great privileges of serving as governor general comes in having the chance to shine a spotlight on important issues facing our country. -

A Commitment to Reconciliation: Canada's Next Steps in the Post

EMILIE DE HAAS ・ Volume 5 n° 9 ・ Spring 2017 A Commitment to Reconciliation: Canada’s Next Steps in the Post-TRC Phase International Human Rights Internships Program - Working Paper Series About the Working Paper Series The Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) Working Paper Series enables the dissemination of papers by students who have participated in the Centre’s International Human Rights Internship Program (IHRIP). Through the program, students complete placements with NGOs, government institutions, and tribunals where they gain practical work experience in human rights investigation, monitoring, and reporting. Students then write a research paper, supported by a peer review process, while participating in a seminar that critically engages with human rights discourses. In accordance with McGill University’s Charter of Students’ Rights, students in this course have the right to submit in English or in French any written work that is to be graded. Therefore, papers in this series may be published in either language. The papers in this series are distributed free of charge and are available in PDF format on the CHRLP’s website. Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. The opinions expressed in these papers remain solely those of the author(s). They should not be attributed to the CHRLP or McGill University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). 1 Abstract This paper explores the connection between a commitment to reconciliation and accountability in the context of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission after the publication of its final report in December of 2015. -

Girls' Sports Reading List

Girls’ Sports Reading List The books on this list feature girls and women as active participants in sports and physical activity. There are books for all ages and reading levels. Some books feature champion female athletes and others are fiction. Most of the books written in the 1990's and 2000’s are still in print and are available in bookstores. Earlier books may be found in your school or public library. If you cannot find a book, ask your librarian or bookstore owner to order it. * The descriptions for these books are quoted with permission from Great Books for Girls: More than 600 Books to Inspire Today’s Girls and Tomorrow’s Women, Kathleen Odean, Ballantine Books, New York, 1997. ~ The descriptions for these books are quoted from Amazon.com. A Turn for Lucas, Gloria Averbuch, illustrations by Yaacov Guterman, Mitten Press, Canada, 2006. Averbuch, author of best-selling soccer books with legends like Brandi Chastain and Anson Dorrance, shares her love of the game with children in this book. This is a story about Lucas and Amelia, the soccer-playing twins who share this love of the game. A Very Young Skater, Jill Krementz, Dell Publishing, New York, NY, 1979. Ages 7-10, 52 p., ($6.95). The story of a 10-year-old female skater told in words and pictures. A Winning Edge, Bonnie Blair with Greg Brown, Taylor Publishing, Dallas, TX, 1996. Ages 8- 12, 38 p., ($14.95). Bonnie Blair shares her passion and motivation for skating, the obstacles that she’s faced, the sacrifices and the victories. -

Complementarity: the Constitutional Role of the Senate of Canada

SENATE SENAT The Honourable V. Peter Harder P.C. L’honorable V. Peter Harder C.P. Government Representative in the Senate Représentant du gouvernement au Sénat CANADA Complementarity: The Constitutional Role of the Senate of Canada April 12, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 A. Complement to the House: A Constitutional Role Rooted in the 7 Appointive Principle B. In the Senate, Self-Restraint is the Constitutional Watchword 11 C. The Senate’s Power to Amend, Legislate and Influence Public Policy 17 D. We “Ping”, But We Generally Ought not “Pong” 28 E. A Prudent Yet Vigilant Approach to Fiscal and Budgetary Initiatives 30 i. Restricted Access to the Purse Strings 30 ii. A Tradition of Vigilance and Self-Restraint on Confidence and 31 Budgetary Matters iii. The Omnibus Caveats 33 F. The Senate Extraordinary and Rarely Used Power to Defeat 37 Government Legislation G. Democratic Deference to the Government’s Election Platform 41 H. Private Members’ Bills and the Senate’s “Pocket” Veto 47 Epilogue: Better Serving Canadians 49 Complementarity: The Constitutional Role of the Senate of Canada April 2018 - Page 1 of 51 INTRODUCTION “If we enact legislation speedily, we are called rubber stamps. If we exercise the constitutional authority which the Senate possesses under the British North America Act, we are told that we are doing something that we have no right to do. I do not know how to satisfy our critics.” The late former Senator Carl Goldenberg, Senate Debates of January 11, 1974 Many senators are working hard to close a credibility gap that was created by many difficult years and prove the Senate’s public value as an appointed upper chamber. -

Debates of the Senate

DEBATES OF THE SENATE 2nd SESSION • 43rd PARLIAMENT • VOLUME 152 • NUMBER 42 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, May 27, 2021 The Honourable GEORGE J. FUREY, Speaker CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: Josée Boisvert, National Press Building, Room 831, Tel. 613-219-3775 Publications Centre: Kim Laughren, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 343-550-5002 Published by the Senate Available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1523 THE SENATE Thursday, May 27, 2021 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. BOVINE SPONGIFORM ENCEPHALOPATHY Prayers. Hon. Paula Simons: Honourable senators, this morning, the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association announced that the World Organization for Animal Health, the OIE, has declared Canada a SENATORS’ STATEMENTS country with a “negligible risk for bovine spongiform encephalopathy.” That is the lowest possible risk for BSE, a development that we can hope will mark the beginning of the end OPIOID CRISIS of trade barriers to Canadian beef around the world. It’s an extraordinary tribute to the Canadian prion disease researchers, Hon. Vernon White: Honourable senators, I’ve spoken about veterinarians, inspectors, farmers and ranchers who have worked the opioid crisis Canada has and is facing twice in the past week. together to achieve this hard-won status. For many of us it is a crisis that impacts the unknown addict, but the reality is very different. It was 18 years ago this week that a case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy was first detected by a provincial lab in Alberta. Today I want to put before you some of those who have died The cow in question had never entered the human food chain. -

George Committees Party Appointments P.20 Young P.28 Primer Pp

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COVERAGE: NEWS, FEATURES, AND ANALYSIS INSIDE HARPER’S TOOTOO HIRES HOUSE LATE-TERM GEORGE COMMITTEES PARTY APPOINTMENTS P.20 YOUNG P.28 PRIMER PP. 30-31 CENTRAL P.35 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1322 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SENATE REFORM NEWS FINANCE Monsef, LeBlanc LeBlanc backs away from Morneau to reveal this expected to shed week Trudeau’s whipped vote on assisted light on deficit, vision for non- CIBC economist partisan Senate dying bill, but Grit MPs predicts $30-billion BY AbbaS RANA are ‘comfortable,’ call it a BY DEREK ABMA Senators are eagerly waiting to hear this week specific details The federal government is of the Trudeau government’s plan expected to shed more light on for a non-partisan Red Cham- Charter of Rights issue the size of its deficit on Monday, ber from Government House and one prominent economist Leader Dominic LeBlanc and Members of the has predicted it will be at least Democratic Institutions Minister Joint Committee $30-billion—about three times Maryam Monsef. on Physician- what the Liberals promised dur- The appearance of the two Assisted ing the election campaign—due to ministers at the Senate stand- Suicide, lower-than-expected tax revenue ing committee will be the first pictured at from a slow economy and the time the government has pre- a committee need for more fiscal stimulus. sented detailed plans to reform meeting on the “The $10-billion [deficit] was the Senate. Also, this is the first Hill. The Hill the figure that was out there official communication between Times photograph based on the projection that the the House of Commons and the by Jake Wright economy was growing faster Senate on Mr. -

Debates of the Senate

Debates of the Senate 1st SESSION . 42nd PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 150 . NUMBER 70 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, November 3, 2016 The Honourable GEORGE J. FUREY Speaker CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: D'Arcy McPherson, National Press Building, Room 906, Tel. 613-995-5756 Publications Centre: Kim Laughren, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 613-947-0609 Published by the Senate Available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1671 THE SENATE Thursday, November 3, 2016 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. international recognition of the importance of his work in our Parliament, in the Senate of Canada, and how we make a mark in Prayers. the world. Our colleague is truly a national and now an international BUSINESS OF THE SENATE champion for genetic fairness. Please join with me in congratulating him and the Canadian Coalition for Genetic The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, before Fairness for the award and especially for their important efforts commencing with Senators' Statements, after consultations to end genetic discrimination in Canada. through the usual channels, it has been agreed that the clerk at the table should stand 10 seconds before the time for a senator's Hon. Senators: Hear, hear! statement expires. When the clerk stands, senators are asked to bring their comments to a close, as the three minutes for statements will, as a general rule, be applied. REMEMBRANCE DAY Hon. Yonah Martin (Deputy Leader of the Opposition): Honourable senators, next week is one of the most important and solemn weeks we commemorate on our national calendar. -

Annual Report 2016 International Paralympic Committee International Paralympic Committee 2 Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 3

International Paralympic Committee Annual Report 2016 International Paralympic Committee International Paralympic Committee 2 Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 3 Annual Report 2016 Contents President’s welcome 4 The Paralympic Movement and the IPC 8 Consolidate the Paralympic Games as a premier sporting event 12 Empower Para athletes and support the development of Para sports 26 Improve the recognition and value of the Paralympic brand 40 Build sustainable funding 48 Shape organisational capability 54 Foster key strategic partnerships 60 World Para Sports 68 Committees and Councils 88 Images Top 50 moments of 2016 92 (c) Photo Credits: Getty Images (1, 4, 5, 7, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 49, 54, 58, 60, 61, 63, 67, 86, 87, 88, 89, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99), Scuola Alpina Predazzo (1, 82, 83), Dan Behr (2, 3), IPC (4, 19, 30, 43), Perdo Vasconcelos (8, 9), Rio 2016 (12, 13), OIS (16, 22, 68, 80, 81, 94, 96), Wagner Meier (17), POCOG (20, 71), IBSF (23), Agitos Foundation (31), Görand Strand (32), Joern Wolter (32, 59), Ales Fevzer (36, 27, 70), European Excellence Awards (46), IPC Academy (59), UN / Eskinder Debebe (62), Agenzia Fotografica (72, 73), Roman Benicky (74, 75, 98), Shuhei Koganezawa (77), Heidi Lehikoinen (78,79), Pedro Vasconcelos (84, 85), Channel 4 (95), Augusto Bizzi (95), Bill Wippert (96), Gene Sweeney Jr. (98) International Paralympic Committee International Paralympic Committee 4 Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 5 President’s welcome Key -

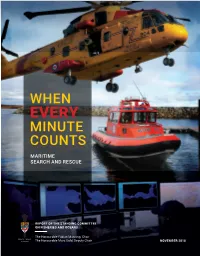

When Every Minute Counts: Maritime

WHEN EVERY MINUTE COUNTS MARITIME SEARCH AND RESCUE REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON FISHERIES AND OCEANS The Honourable Fabian Manning, Chair SBK>QB SK>Q CANADA The Honourable Marc Gold, Deputy Chair NOVEMBER 2018 For more information please contact us: by email: [email protected] by mail: The Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans Senate, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: www.senate-senat.ca/ The Senate is on Twitter: @SenateCA, follow the committee using the hashtag #pofo Ce rapport est également offert en français TABLE OF CONTENTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE ............................................................................................................. I ORDER OF REFERENCE ......................................................................................................................... III LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... V RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................................................................................... VI INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1: SEARCH AND RESCUE ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 International Legal Framework ................................................................................................ -

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Report

INSPIRING CANADIANS - IN SPORT AND LIFE 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT Message from the Chair – May 2016 On behalf of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame’s Board of Governors, I am pleased to present the 2015 Annual Report. 2015 marked the 60th anniversary of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame’s establishment in 1955 at Toronto’s CNE grounds by Harry Price. Since its move to Calgary in 2011, Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame continues to be a truly national organization with programs, events, and traveling exhibits across our country. We are proud to include a total of 65 sports represented by our 605 inducted Honoured Members spanning nearly 150 years of Canadian sport history. The Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame 2015 Induction Celebrations Presented by Canadian Tire were a huge success reaching over one million Canadians across the country. The nationally televised gala was a tribute to the Class of 2015 inductees selected to receive Canada’s highest sporting honour. In recognition of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame’s 60th anniversary and 2015 being proclaimed the Year of Sport by our Patron David Johnston, Governor General of 2015-16 Board of Governors Canada, a second Legends group was identified. This amazing group of 46 individuals made their contributions to sport and to Canada primarily before 1955. These remarkable Colin P. MacDonald, Chair people fought for gender equality, broke down racial barriers, and promoted the development Geoff Beattie Sylvie Bigras of sport in Canada. The Class of 2015 and the Legends Class are a true inspiration to all Michelle Cameron-Coulter Canadians and we are proud to share their stories and life lessons. -

Resource Guide

Resources & Supports National Indigenous History Month 2021 Event Resources The Honorable Murray Sinclair His Honour Murray Sinclair served the justice system in Manitoba for over 40 years. He was the first Aboriginal Judge appointed in Manitoba and Canada’s second. He served as Co-Chair of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in Manitoba and as Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). As head of the TRC, he participated in hundreds of hearings across Canada, culminating in the issuance of the TRC’s report in 2015. He also oversaw an active multi-million dollar fundraising program to support various TRC events and activities, and to allow survivors to travel to attend TRC events. The Honorable Murray Sinclair was appointed to the Senate on April 2, 2016. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history, began to be implemented in 2007. One of the elements of the agreement was the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) to facilitate reconciliation among former students, their families, their communities and all Canadians. The official mandate of the TRC is found in Schedule "N" of the Settlement Agreement which includes the principles that guided the commission in its important work. Read the TRC’s 94 calls to action. Digging Roots The beating hearts of Digging Roots, founding duo ShoShona Kish and Raven Kanatakta, have built a home for a talented community of players and collaborators including their son, drummer Skye Polson and Hill Kourkoutis. More than a band, Digging Roots have taken their place at the frontline of the fight for equity and representation in the arts, with involvement in industry advocacy and organization, including the International Indigenous Music Summit and Ishkode Records, to empower arts communities worldwide. -

BY JUSTICE MURRAY SINCLAIR Rock Us At

DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 93 NUMBER 3 NEWSMAGAZINE OF THE MANITOBA TEACHERS’ SOCIETY BY JUSTICE MURRAY SINCLAIR Rock us at YHA 2015 We’re looking for amazing voices, musicians and dancers! Know a talented student or group who can rock our Young Humanitarian Awards? We’ll be featuring three acts at our May 20, 2015, YHA show at the Fairmont Winnipeg. Send your tip along with a YouTube link to [email protected] Must be public school students. Honorarium provided. DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 93 NUMBER 3 NEWSMAGAZINE OF THE MANITOBA TEACHERS’ SOCIETY P. 4 President’s Column P. 5 Inside MTS PD in pix P. 12 Teachers pack Fab5 and SAGE events. P. 15 The year everyone graduated Portfolio Media Research finds old P. 20 can’t experiment resulted believe in huge educational themselves. gains. P. 11 Hockey and health Winnipeg Jets Foundation creates P. 18 mental health program for students. Open books P. 6 Little, outdoor Teaching history libraries are Justice Murray Sinclair popping up on need to teach about in Manitoba. residential schools. PRESIDENT’S COLUMN PAUL OLSON Editor George Stephenson, [email protected] Design Tamara Paetkau, Krista Rutledge write this on the eve of Remembrance Day, and also in the long shadow of Photography the PCAP report, which confirmed we’re the worst teachers in the country. (It had graphs, so it must be true.) Matea Tuhtar IOne school I visited recently has a student population of 400, but last year Circulation processed 1,100 registrations—almost a 300 per cent rate of annual “churn”, mostly with federally funded First Nations schools.