Belt Sourik Village Council V. the Government of Israel Jason Litwack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building a Protective Wall Around Terrorists

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 28, Issue 3 2004 Article 10 Building a Protective Wall Around Terrorists – How the International Court of Justice’s Ruling in The Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Made the World Safer for Terrorists and More Dangerous for Member States of the United Nations Rebecca Kahan∗ ∗ Copyright c 2004 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Building a Protective Wall Around Terrorists – How the International Court of Justice’s Ruling in The Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Made the World Safer for Terrorists and More Dangerous for Member States of the United Nations Rebecca Kahan Abstract Part I of this Note will examine two recent actions in the war against international terror- ism: the Israeli plan to build a separation barrier between Israel and the OPT, and the invasion of Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. Part II will discuss two important deviations by the ICJ from past interpretation of international law that were announced in the advisory proceed- ings against Israel: a new elucidation by the ICJ regarding principles of judicial propriety and a new analysis of the abilities of States to act in self-defense under Article 51 of the U.N. Charter. Part III will address the impact on the international community’s fight against terrorism, and the role of the ICJ as an international entity. BUILDING A PROTECTIVE WALL AROUND TERRORISTS HOW THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE'S RULING IN THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF A WALL IN THE OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY MADE THE WORLD SAFER FOR TERRORISTS AND MORE DANGEROUS FOR MEMBER STATES OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rebecca Kahan* INTRODUCTION The nature of the threats posed to States has changed since the adoption of the U.N. -

Agellan Commercial Real Estate Investment Trust Annual Information

AGELLAN COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUST ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 March 29, 2018 Table of Contents GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................... 3 CERTAIN REFERENCES AND FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS .................................................................. 7 NON‐IFRS FINANCIAL MEASURES ................................................................................................................. 8 LEGAL STRUCTURE OF AGELLAN ................................................................................................................. 10 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS .............................................................................................. 12 Three Year History ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Description of the Business ....................................................................................................................... 14 THE REAL ESTATE PORTFOLIO ..................................................................................................................... 18 Occupancy and Leasing ............................................................................................................................. 18 Geographic Diversification ....................................................................................................................... -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

The Wall's Impact in the Occupied West Bank: a Bayesian Approach To

econometrics Article The Wall’s Impact in the Occupied West Bank: A Bayesian Approach to Poverty Dynamics Using Repeated Cross-Sections Tareq Sadeq 1,2 and Michel Lubrano 2* ID 1 Department of Economics, Birzeit University, Birzeit, West Bank 627, Palestine; [email protected] 2 Aix-Marseille Univ., CNRS, EHESS, Centrale Marseille, AMSE, Ilot Bernard Dubois, 5 Bd Maurice Bourdet, 13001 Marseille, France * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-413-55-25-57 Received: 3 December 2017; Accepted: 22 May 2018; Published: 30 May 2018 Abstract: In 2002, the Israeli government decided to build a wall inside the occupied West Bank. The wall had a marked effect on the access to land and water resources as well as to the Israeli labour market. It is difficult to include the effect of the wall in an econometric model explaining poverty dynamics as the wall was built in the richer region of the West Bank. So a diff-in-diff strategy is needed. Using a Bayesian approach, we treat our two-period repeated cross-section data set as an incomplete data problem, explaining the income-to-needs ratio as a function of time invariant exogenous variables. This allows us to provide inference results on poverty dynamics. We then build a conditional regression model including a wall variable and state dependence to see how the wall modified the initial results on poverty dynamics. We find that the wall has increased the probability of poverty persistence by 58 percentage points and the probability of poverty entry by 18 percentage points. Keywords: Bayesian inference; pseudo panels; data augmentation; walls; poverty dynamics JEL Classification: C11; C33; I32; O15 1. -

11 July 2006 Mumbai Train Bombings

11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings July 2006 Mumbai train bombings One of the bomb-damaged coaches Location Mumbai, India Target(s) Mumbai Suburban Railway Date 11 July 2006 18:24 – 18:35 (UTC+5.5) Attack Type Bombings Fatalities 209 Injuries 714 Perpetrator(s) Terrorist outfits—Student Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT; These are alleged perperators as legal proceedings have not yet taken place.) Map showing the 'Western line' and blast locations. The 11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings were a series of seven bomb blasts that took place over a period of 11 minutes on the Suburban Railway in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and India's financial capital. 209 people lost their lives and over 700 were injured in the attacks. Details The bombs were placed on trains plying on the western line of the suburban ("local") train network, which forms the backbone of the city's transport network. The first blast reportedly took place at 18:24 IST (12:54 UTC), and the explosions continued for approximately eleven minutes, until 18:35, during the after-work rush hour. All the bombs had been placed in the first-class "general" compartments (some compartments are reserved for women, called "ladies" compartments) of several trains running from Churchgate, the city-centre end of the western railway line, to the western suburbs of the city. They exploded at or in the near vicinity of the suburban railway stations of Matunga Road, Mahim, Bandra, Khar Road, Jogeshwari, Bhayandar and Borivali. -

FEDERAL SCHOOL CODES for 2014-2015 Effective August 1, 2014

FEDERAL SCHOOL CODES For 2014-2015 Effective August 1, 2014 Table of Contents Domestic Page Alabama .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Alaska .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 American Samoa ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Arizona ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Arkansas .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 California ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Colorado ........................................................................................................................................................ 21 Connecticut .................................................................................................................................................... 23 Delaware ....................................................................................................................................................... -

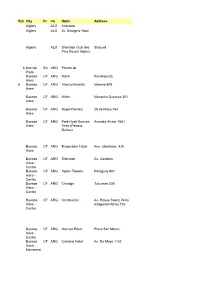

Rat E City Pr Co Hotel Address Algiers ALG Sheraton Algiers ALG St

Rat City Pr Co Hotel Address e Algiers ALG Sheraton Algiers ALG St. George's Hotel Algiers ALG Sheraton Club des Staoueli Pins Resort Algiers 6 Mar del BA ARG Provincial Plata Buenos CF ARG Meliá Reconquista Aires 6 Buenos CF ARG Intercontinental Moreno 809 Aires Buenos CF ARG Hilton Macacha Guemes 351 Aires Buenos CF ARG Regal Pacifico 25 de Mayo 764 Aires Buenos CF ARG Park Hyatt Buenos Avenida Alvear 1661 Aires Aires (Palacio Duhau) Buenos CF ARG Emperador Hotel Ave. Libertador, 420 Aires Buenos CF ARG Sheraton Av. Cordoba Aires - Centro Buenos CF ARG Aspen Towers Paraguay 857 Aires - Centro Buenos CF ARG Claridge Tucuman 535 Aires - Centro Buenos CF ARG Continental Av. Roque Saenz Peña Aires - (Diagonal Norte) 725 Centro Buenos CF ARG Marriott Plaza Plaza San Mertin Aires - Centro Buenos CF ARG Castelar Hotel Av. De Mayo 1152 Aires - Monserrat 5 Buenos CF ARG Alan Faena Martha Salotti 445 Aires - Puerto Madero 7 Buenos CF ARG Recoleta Calle J. L. Pagano 2684 Aires - REcoleta Buenos CF ARG Four Seasons Recova Aires - Recoleta Buenos CF ARG De Alvear Marcel T. de Alvear Aires - Recoleta Buenos CF ARG Sheraton Buenos Plaza de los Ingleses Aires - Aires Retiro 6 Mendoza CU ARG Aconcagua San Lorenzo 545 (cerca de Plaza de Italia) Mendoza CU ARG Sheraton Mendoza CU ARG Premium Tower Puerto MI ARG Sheraton Iguazu Puerto MI ARG Panoramic Paraguay 372 Iguazu Puerto MI ARG Iguazu Grand Hotel Iguazu Puerto MI ARG Esturion Iguazu Puerto MI ARG Saint George Iguazu Cachi SA ARG Sala de Payogasta Ruta Nac. -

Collective Defense by Common Property Regimes: the Rise and Fall of the Kibbutz∗

Collective Defense by Common Property Regimes: the Rise and Fall of the Kibbutz∗ Liang Diaoy April 2019 Abstract Common property regimes have long been considered inefficient and short lived, as they en- courage high-productivity individuals to leave and shirking among those who stay. In contrast, kibbutzim { voluntary common property settlements in Israel { have lasted almost for a century. Recently, about 75% of kibbutzim abandoned the equal-sharing rule and paid differential salaries to members, based on their contributions. To explain the long persistence of the kibbutzim, as well as the recent kibbutz privatization, I develop a model that highlights the public defense provided by common property regimes. The model predicts that the privatization of common property regimes can be attributed to the decrease of external threats. To test this prediction, I construct a kibbutzim-level panel data set that contains the terrorist attacks near each kibbutz and the institutional status (i.e. preserving the equal-sharing rule or not) of each kibbutz in the years from 1986 to 2014. The empirical results show that an increase in the number of Israeli deaths near a kibbutz significantly decreases the probability that the kibbutz shift away from equal sharing. 1 Introduction Common property regimes, a property rights arrangement in which a group of resource users share rewards and duties related to a resource, have long been considered inefficient.1 The inefficiency comes from two sources: low-productivity individuals tend to remain in the regime, while high- productivity individuals tend to leave (adverse selection); and equal income sharing, regardless of effort, encourages shirking (moral hazard). -

Title X Family Planning Directory November 2018

Title X Family Planning Directory November 2018 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) Regions Not Shown On Map: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, Guam, Republic of Palau, Federate States of Micronesia, Republic of the Marshall Islands Region 1 – Boston Region 6 – Dallas Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas Rhode Island, and Vermont Region 2 – New York Region 7 – Kansas City New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska and the Virgin Islands Region 3 – Philadelphia Region 8 – Denver Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia and Wyoming Region 4 – Atlanta Region 9 – San Francisco Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Marshall Islands, and Republic of Palau Region 5 – Chicago Region 10 – Seattle Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington and Wisconsin Title X Family Planning Directory | 2018 Title X Directory - November 2018 Directory of Grantees - November 2018 Legend Grantee Sub-Recipient Service Site Region 1 Grantee Sub-Recipient Service Site Street Address City State Zip Phone URL Action for Boston Community Development, Inc., Family Planning 178 Tremont St Boston MA 02111 (617) -

Delegation of the European Union

European Union UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL 17th Session (30 May - 17 June 2011) ______ Item 7 ______ Statement by H.E. Ambassador András DÉKÁNY Permanent Representative of Hungary to the United Nations Office in Geneva on behalf of the European Union Geneva, 14 June 2011 Check against delivery Geneva, 14 June 2011 UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL 17th Session (30 May – 17 June 2011) EU Statement General Debate Item 7 Mr President, I have the honour to speak on behalf of the European Union. The fundamental changes across the Arab world have made the need for progress on the Middle East Peace Process all the more urgent. Recent events have indeed shown the necessity of heeding the legitimate aspirations of peoples in the region, including those of Palestinians for statehood, and of Israelis for security. Within the context of its ongoing engagement, the EU is deeply concerned about the continuing stalemate in the Peace Process and calls for the urgent resumption of direct negotiations leading to a comprehensive solution on all tracks. Our goal remains a just and lasting resolution to the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, with the State of Israel and an independent, democratic, contiguous, sovereign and viable State of Palestine, living side by side in peace and security and mutual recognition. A way must be found through negotiations to resolve the status of Jerusalem as the future capital of two States. Recalling the Berlin Declaration, the EU reiterates its readiness to recognize a Palestinian State when appropriate. Justice, rule of law and respect for international human rights and international humanitarian law are the cornerstones of peace and security. -

The Impact of Foreign Aid and Donations to Palestine on Development of Its Economy Under Alternative Israeli- Palestinian Economic Interaction Regimes

The Impact of Foreign Aid and Donations to Palestine on Development of its Economy under Alternative Israeli- Palestinian Economic Interaction Regimes Sharbel Shoukair The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. Submitted to the University of Portsmouth Supervisor: Dr. Judith Rich December 2013 Abstract The main goal of the thesis is to examine whether the Palestinian economy suffers from "Dutch Disease" symptoms, and if so what are its sources. Dutch Disease has been widely used to explain why foreign development aid can be ineffective in generating economic growth, even though it can break the vicious cycle of low income, low saving, low investment, low sustainable growth and even negative growth. In most cases, the disease is due to appreciation of local currency. However, the Palestinians use the Israeli Shekel and also the Jordanian Dinar and the Egyptian Lira. Thus, the sources of the symptoms of the Dutch Disease in the Palestinian economy might be explained by the influx of foreign aid arising because of terror attacks and retaliations and the economic policy and constraints that are imposed mainly by Israel. The theoretical and empirical efforts of the thesis to determine the causality direction between foreign aid and growth include the following: I. The national accounting identities are used to express the gross domestic product (GDP) in terms of foreign currency and the proportion between import and uses. I found empirically that due to the political- economic constraints in the case of the Palestinian economy, the factors mentioned above are almost entirely exogenous and, under the existing economic- political constraints, foreign development aid had only a small chance to significantly boost the tradable sectors.