Design Attributes of Educational Computer Software for Optimising Girls’ Participation in Educational Game Playing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

JAM-BOX Retro PACK 16GB AMSTRAD

JAM-BOX retro PACK 16GB BMX Simulator (UK) (1987).zip BMX Simulator 2 (UK) (19xx).zip Baby Jo Going Home (UK) (1991).zip Bad Dudes Vs Dragon Ninja (UK) (1988).zip Barbarian 1 (UK) (1987).zip Barbarian 2 (UK) (1989).zip Bards Tale (UK) (1988) (Disk 1 of 2).zip Barry McGuigans Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Batman (UK) (1986).zip Batman - The Movie (UK) (1989).zip Beachhead (UK) (1985).zip Bedlam (UK) (1988).zip Beyond the Ice Palace (UK) (1988).zip Blagger (UK) (1985).zip Blasteroids (UK) (1989).zip Bloodwych (UK) (1990).zip Bomb Jack (UK) (1986).zip Bomb Jack 2 (UK) (1987).zip AMSTRAD CPC Bonanza Bros (UK) (1991).zip 180 Darts (UK) (1986).zip Booty (UK) (1986).zip 1942 (UK) (1986).zip Bravestarr (UK) (1987).zip 1943 (UK) (1988).zip Breakthru (UK) (1986).zip 3D Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Bride of Frankenstein (UK) (1987).zip 3D Grand Prix (UK) (1985).zip Bruce Lee (UK) (1984).zip 3D Star Fighter (UK) (1987).zip Bubble Bobble (UK) (1987).zip 3D Stunt Rider (UK) (1985).zip Buffalo Bills Wild West Show (UK) (1989).zip Ace (UK) (1987).zip Buggy Boy (UK) (1987).zip Ace 2 (UK) (1987).zip Cabal (UK) (1989).zip Ace of Aces (UK) (1985).zip Carlos Sainz (S) (1990).zip Advanced OCP Art Studio V2.4 (UK) (1986).zip Cauldron (UK) (1985).zip Advanced Pinball Simulator (UK) (1988).zip Cauldron 2 (S) (1986).zip Advanced Tactical Fighter (UK) (1986).zip Championship Sprint (UK) (1986).zip After the War (S) (1989).zip Chase HQ (UK) (1989).zip Afterburner (UK) (1988).zip Chessmaster 2000 (UK) (1990).zip Airwolf (UK) (1985).zip Chevy Chase (UK) (1991).zip Airwolf 2 (UK) -

Downloading Or Purchasing Online At

Hunting Viruses in Crocodiles Viral and endogenous retrovira detection and characterisation in farmed crocodiles JULY 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 12/011 Hunting Viruses in Crocodiles Viral and endogenous retroviral detection and characterisation in farmed crocodiles Lorna Melville, Steven Davis, Cathy Shilton, Sally Isberg, Amanda Chong, Jaime Gongora July 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 12/011 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-002461 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-366-6 ISSN 1440-6845 Hunting Viruses in Crocodiles: Viral and endogenous retroviral detection and characterisation in farmed crocodiles Publication No. 12/011 Project No. PRJ-002461 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. -

Playstation Games

The Video Game Guy, Booths Corner Farmers Market - Garnet Valley, PA 19060 (302) 897-8115 www.thevideogameguy.com System Game Genre Playstation Games Playstation 007 Racing Racing Playstation 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure Action & Adventure Playstation 102 Dalmatians Puppies to the Rescue Action & Adventure Playstation 1Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 2Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 3D Baseball Baseball Playstation 3Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 40 Winks Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 2 Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 3 Electrosphere Other Playstation Aces of the Air Other Playstation Action Bass Sports Playstation Action Man Operation EXtreme Action & Adventure Playstation Activision Classics Arcade Playstation Adidas Power Soccer Soccer Playstation Adidas Power Soccer 98 Soccer Playstation Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Iron and Blood RPG Playstation Adventures of Lomax Action & Adventure Playstation Agile Warrior F-111X Action & Adventure Playstation Air Combat Action & Adventure Playstation Air Hockey Sports Playstation Akuji the Heartless Action & Adventure Playstation Aladdin in Nasiras Revenge Action & Adventure Playstation Alexi Lalas International Soccer Soccer Playstation Alien Resurrection Action & Adventure Playstation Alien Trilogy Action & Adventure Playstation Allied General Action & Adventure Playstation All-Star Racing Racing Playstation All-Star Racing 2 Racing Playstation All-Star Slammin D-Ball Sports Playstation Alone In The Dark One Eyed Jack's Revenge Action & Adventure -

Website Listing Ajax

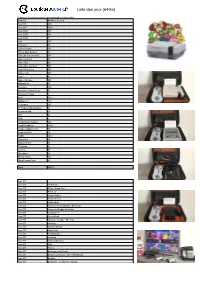

Liste des jeux (64Go) Cliquez sur le nom des consoles pour descendre au bon endroit Console Nombre de jeux Atari ST 274 Atari 800 5627 Atari 2600 457 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 51 C64 150 Channel F 34 Coleco Vision 151 Family Disk System 43 FBA Libretro (arcade) 647 Game & watch 58 Game Boy 621 Game Boy Advance 951 Game Boy Color 501 Game gear 277 Lynx 84 Mame (arcade) 808 Nintento 64 78 Neo-Geo 152 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 NES 1812 Odyssey 2 125 Pc Engine 291 Pc Engine Supergraphx 97 Pokémon Mini 26 PS1 54 PSP 2 Sega Master System 288 Sega Megadrive 1030 Sega megadrive 32x 30 Sega sg-1000 59 SNES 1461 Stellaview 66 Sufami Turbo 15 Thomson 82 Vectrex 75 Virtualboy 24 Wonderswan 102 WonderswanColor 83 Total 16877 Atari ST Atari ST 10th Frame Atari ST 500cc Grand Prix Atari ST 5th Gear Atari ST Action Fighter Atari ST Action Service Atari ST Addictaball Atari ST Advanced Fruit Machine Simulator Atari ST Advanced Rugby Simulator Atari ST Afterburner Atari ST Alien World Atari ST Alternate Reality - The City Atari ST Anarchy Atari ST Another World Atari ST Apprentice Atari ST Archipelagos Atari ST Arcticfox Atari ST Artificial Dreams Atari ST Atax Atari ST Atomix Atari ST Backgammon Royale Atari ST Balance of Power - The 1990 Edition Atari ST Ballistix Atari ST Barbarian : Le Guerrier Absolu Atari ST Battle Chess Atari ST Battle Probe Atari ST Battlehawks 1942 Atari ST Beach Volley Atari ST Beastlord Atari ST Beyond the Ice Palace Atari ST Black Tiger Atari ST Blasteroids Atari ST Blazing Thunder Atari ST Blood Money Atari ST BMX Simulator Atari ST Bob Winner Atari ST Bomb Jack Atari ST Bumpy Atari ST Burger Man Atari ST Captain Fizz Meets the Blaster-Trons Atari ST Carrier Command Atari ST Cartoon Capers Atari ST Catch 23 Atari ST Championship Baseball Atari ST Championship Cricket Atari ST Championship Wrestling Atari ST Chase H.Q. -

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Acid Drop Actionauts Activision Decathlon, the Adventure A

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Acid Drop Actionauts Activision Decathlon, The Adventure Adventures of TRON Air Raid Air Raiders Airlock Air-Sea Battle Alfred Challenge (France) (Unl) Alien Alien Greed Alien Greed 2 Alien Greed 3 Allia Quest (France) (Unl) Alligator People, The Alpha Beam with Ernie Amidar Aquaventure Armor Ambush Artillery Duel AStar Asterix Asteroid Fire Asteroids Astroblast Astrowar Atari Video Cube A-Team, The Atlantis Atlantis II Atom Smasher A-VCS-tec Challenge AVGN K.O. Boxing Bachelor Party Bachelorette Party Backfire Backgammon Bank Heist Barnstorming Base Attack Basic Math BASIC Programming Basketball Battlezone Beamrider Beany Bopper Beat 'Em & Eat 'Em Bee-Ball Berenstain Bears Bermuda Triangle Berzerk Big Bird's Egg Catch Bionic Breakthrough Blackjack BLiP Football Bloody Human Freeway Blueprint BMX Air Master Bobby Is Going Home Boggle Boing! Boulder Dash Bowling Boxing Brain Games Breakout Bridge Buck Rogers - Planet of Zoom Bugs Bugs Bunny Bump 'n' Jump Bumper Bash BurgerTime Burning Desire (Australia) Cabbage Patch Kids - Adventures in the Park Cakewalk California Games Canyon Bomber Carnival Casino Cat Trax Cathouse Blues Cave In Centipede Challenge Challenge of.... Nexar, The Championship Soccer Chase the Chuckwagon Checkers Cheese China Syndrome Chopper Command Chuck Norris Superkicks Circus Atari Climber 5 Coco Nuts Codebreaker Colony 7 Combat Combat Two Commando Commando Raid Communist Mutants from Space CompuMate Computer Chess Condor Attack Confrontation Congo Bongo -

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Acid Drop Actionauts Activision Decathlon, The Adventure Adventures of TRON Air Raid Air Raiders Airlock Air-Sea Battle Alfred Challenge Alien Alien Greed Alien Greed 2 Alien Greed 3 Allia Quest Alligator People, The Alpha Beam with Ernie Amidar Aquaventure Armor Ambush Artillery Duel AStar Asterix Asteroid Fire Asteroids Astroblast Astrowar Atari Video Cube A-Team, The Atlantis Atlantis II Atom Smasher A-VCS-tec Challenge AVGN K.O. Boxing Bachelor Party Bachelorette Party Backfire Backgammon Bank Heist Barnstorming Base Attack Basic Math BASIC Programming Basketball Battlezone Beamrider Beany Bopper Beat 'Em & Eat 'Em Bee-Ball Berenstain Bears Bermuda Triangle Berzerk Big Bird's Egg Catch Bionic Breakthrough Blackjack BLiP Football Bloody Human Freeway Blueprint BMX Air Master Bobby Is Going Home Boggle Boing! Boulder Dash Bowling Boxing Brain Games Breakout Bridge Buck Rogers - Planet of Zoom Bugs Bugs Bunny Bump 'n' Jump Bumper Bash BurgerTime Burning Desire Cabbage Patch Kids - Adventures in the Park Cakewalk California Games Canyon Bomber Carnival Casino Cat Trax Cathouse Blues Cave In Centipede Challenge Challenge of.... Nexar, The Championship Soccer Chase the Chuckwagon Checkers Cheese China Syndrome Chopper Command Chuck Norris Superkicks Circus Atari Climber 5 Coco Nuts Codebreaker Colony 7 Combat Combat Two Commando Commando Raid Communist Mutants from Space CompuMate Computer Chess Condor Attack Confrontation Congo Bongo Conquest of Mars Cookie Monster Munch Cosmic -

45 Years of Arcade Gaming

WWW.OLDSCHOOLGAMERMAGAZINE.COM ISSUE #2 • JANUARY 2018 Midwest Gaming Classic midwestgamingclassic.com CTGamerCon .................. ctgamercon.com JANUARY 2018 • ISSUE #2 EVENT UPDATE BRETT’S BARGAIN BIN Portland Classic Gaming Expo Donkey Kong and Beauty and the Beast 06 BY RYAN BURGER 38BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF WE DROPPED BY FEATURE Old School Pinball and Arcade in Grimes, IA 45 Years of Arcade Gaming: 1980-1983 08 BY RYAN BURGER 40BY ADAM PRATT THE WALTER DAY REPORT THE GAME SCHOLAR When President Ronald Reagan Almost Came The Nintendo Odyssey?? 10 To Twin Galaxies 43BY LEONARD HERMAN BY WALTER DAY REVIEW NEWS I Didn’t Know My Retro Console Could Do That! 2018 Old School Event Calendar 45 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF 12 BY RYAN BURGER FEATURE REVIEW Inside the Play Station, Enter the Dragon Nintendo 64 Anthology 46 BY ANTOINE CLERC-RENAUD 13 BY KELTON SHIFFER FEATURE WE STOPPED BY Controlling the Dragon A Gamer’s Paradise in Las Vegas 51 BY ANTOINE CLERC-RENAUD 14 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF PUREGAMING.ORG INFO GAME AND MARKET WATCH Playstation 1 Pricer Game and Market Watch 52 BY PUREGAMING.ORG 15 BY DAN LOOSEN EVENT UPDATE Free Play Florida Publisher 20BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF Ryan Burger WESTOPPED BY Business Manager Aaron Burger The Pinball Hall of Fame BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF Design Director 22 Issue Writers Kelton Shiffer Jacy Leopold MICHAEL THOMASSON’S JUST 4 QIX Ryan Burger Michael Thomasson Design Assistant Antoine Clerc-Renaud Brett Weiss How High Can You Get? Marc Burger Walter Day BY MICHAEL THOMASSON 24 Brad Feingold Editorial Board Art Director KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA Todd Friedman Dan Loosen Thor Thorvaldson Leonard Herman Doc Mack Where It All Began Dan Loosen Billy Mitchell BY SHAWN PAUL JONES + WALTER DAY Circulation Manager Walter Day 26 Kitty Harr Shawn Paul Jones Adam Pratt KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA King of Kong Movie Review 28 BY BRAD FEINGOLD HOW TO REACH OLD SCHOOL GAMER: Tel / Fax: 515-986-3344 Postage paid at Grimes, IA and additional mailing KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA Web: www.oldschoolgamermagazine.com locations. -

Game Boy Color Games

Game Boy Color Games Title: Licensee Released 10 Pin Bowling Majesco August 1999 1942 Capcom May 2000 3D Ultra Thrillride Pinball Havas Interactinve December 2000 Action Man: Search For Base X THQ February 2001 Airforce Delta Konami November 2000 Aliens: Thanatos Encounter THQ March 2001 All-Star Baseball 2000 Acclaim May 1999 All-Star Baseball 2001 Acclaim June 2000 Alone in the Dark Infogrames June 2001 Animorphs Ubi Soft November 2000 Antz Racing Acclaim June 2001 Armada FX Racers Metro 3D Studios September 2000 Armorines Acclaim December 1999 Army Men 3DO February 2000 Army Men: Air Combat 3DO November 2000 Army Men: Portal Runner 3DO September 2001 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes 2 3DO November 2000 Aurthur's Absolutely Fun Day Mattel September 2000 Austin Powers: Oh Behave Take 2 Interactive September 2000 Austin Powers: Welcome to my Underground Lair Take 2 Interactive September 2000 Barbie Kelly Club Mattel Barbie Magic Genie Mattel November 2000 Barbie Pet Rescue Mattel September 2001 Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker Kemco November 2000 Batman: Chaos in Gotham City Ubi Soft March 2001 Battletanx 3DO March 2000 Billy Bob's Huntin' and Fishing Midway November 1999 Bionic Commando: Elite Forces Nintendo January 2000 Blade Activision December 2000 Blue's Clues Alphabet Book Mattel January 2001 Bob the Builder THQ September 2001 Bomberman Max: Blue Champion Vatical Entertainment May 2000 Bomberman Max: Red Chamion Vatical Entertainment May 2000 Buffy the Vampire Slayer THQ September 2000 Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle 4 Kemco July 2000 Bust A -

Lista De Los Juegos Versión 32 Gb Arcade

LISTA DE LOS JUEGOS VERSIÓN 32 GB SISTEMA JUEGOS Arcade 855 Arcade MAME 798 Atari 2600 473 Atari 7800 49 Gameboy 625 Gameboy Color 545 Gameboy Advance 952 Gamegear 277 Game & Watch 51 Lynx 85 Master System 288 Megadrive 813 NeoGeo 158 NeoGeo Pocket Color 119 NES 1818 PC DOS 36 PC-Engine 289 PC-Engine Super Grafx 101 Sega 32X 46 Super Nintendo 1375 Vectrex 45 Virtual Boy 26 WonderSwan Color 129 TOTAL 9953 ARCADE Sistema # Titulo del juego Arcade 1 ASURA BUSTER - ETERNAL WARRIORS Arcade 2 1942 Arcade 3 1000 MIGLIA: GREAT 1000 MILES RALLY Arcade 4 1941: COUNTER ATTACK Arcade 5 1945K III Arcade 6 2020 SUPER BASEBALL Arcade 7 4 EN RAYA Arcade 8 4 FUN IN 1 Arcade 9 4 PLAYER INPUT TEST Arcade 10 4-D WARRIORS Arcade 11 7 ORDI Arcade 12 A. D. 2083 Arcade 13 A.B. COP Arcade 14 ACE ATTACKER Arcade 15 ACT-FANCER CYBERNETICK HYPER WEAPON Arcade 16 ACTION FIGHTER Arcade 17 ADVENTURE QUIZ 2 - HATENA? NO DAIBOUKEN Arcade 18 ADVENTURE QUIZ CAPCOM WORLD 2 Arcade 19 AFTER BURNER II !1 Arcade 20 AGENT SUPER BOND Arcade 21 AGRESS - MISSILE DAISENRYAKU Arcade 22 AH EIKOU NO KOSHIEN Arcade 23 AIR ATTACK Arcade 24 AIR BUSTER: TROUBLE SPECIALTY RAID UNIT Arcade 25 AIR GALLET Arcade 26 AJAX Arcade 27 ALCON Arcade 28 ALEX KIDD: THE LOST STARS Arcade 29 ALI BABA AND 40 THIEVES Arcade 30 ALIEN CHALLENGE Arcade 31 ALIEN SECTOR Arcade 32 ALIEN STORM Arcade 33 ALIEN SYNDROME Arcade 34 ALIENS Arcade 35 ALTERED BEAST Arcade 36 AMBUSH Arcade 37 AMIDAR Arcade 38 ANGEL KIDS Arcade 39 ANTEATER Arcade 40 AQUA JACK Arcade 41 ARABIAN Arcade 42 ARBALESTER Arcade 43 ARCADIA Arcade 44 ARK AREA Arcade 45 ARKANOID Arcade 46 ARKANOID - REVENGE OF DOH Arcade 47 ARMED FORMATION Arcade 48 ARMED POLICE BATRIDER Arcade 49 ARMORED CAR Arcade 50 ASHITA NO JOE Arcade 51 ASHURA BLASTER Arcade 52 ASURA BLADE - SWORD OF DYNASTY Arcade 53 ATHENA NO HATENA ? Arcade 54 ATOMIC POINT Arcade 55 AURAIL Arcade 56 AVENGERS Arcade 57 AZTARAC Arcade 58 AZURIAN ATTACK Arcade 59 B.C.