Mineral Resources Report for Suffolk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing the Chronostratigraphic Fidelity of Sedimentary Geological Outcrops in the Pliocene–Pleistocene Red Crag Formation, Eastern England

Downloaded from http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 25, 2021 Research article Journal of the Geological Society Published Online First https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2019-056 Where does the time go? Assessing the chronostratigraphic fidelity of sedimentary geological outcrops in the Pliocene–Pleistocene Red Crag Formation, eastern England Neil S. Davies1*, Anthony P. Shillito1 & William J. McMahon2 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, UK 2 Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Princetonlaan 8a, Utrecht 3584 CB, Netherlands NSD, 0000-0002-0910-8283; APS, 0000-0002-4588-1804 * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: It is widely understood that Earth’s stratigraphic record is an incomplete record of time, but the implications that this has for interpreting sedimentary outcrop have received little attention. Here we consider how time is preserved at outcrop using the Neogene–Quaternary Red Crag Formation, England. The Red Crag Formation hosts sedimentological and ichnological proxies that can be used to assess the time taken to accumulate outcrop expressions of strata, as ancient depositional environments fluctuated between states of deposition, erosion and stasis. We use these to estimate how much time is preserved at outcrop scale and find that every outcrop provides only a vanishingly small window onto unanchored weeks to months within the 600–800 kyr of ‘Crag-time’. Much of the apparently missing time may be accounted for by the parts of the formation at subcrop, rather than outcrop: stratigraphic time has not been lost, but is hidden. The time-completeness of the Red Crag Formation at outcrop appears analogous to that recorded in much older rock units, implying that direct comparison between strata of all ages is valid and that perceived stratigraphic incompleteness is an inconsequential barrier to viewing the outcrop sedimentary-stratigraphic record as a truthful chronicle of Earth history. -

Neogene Stratigraphy of the Langenboom Locality (Noord-Brabant, the Netherlands)

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw | 87 - 2 | 165 - 180 | 2008 Neogene stratigraphy of the Langenboom locality (Noord-Brabant, the Netherlands) E. Wijnker1'*, T.J. Bor2, F.P. Wesselingh3, D.K. Munsterman4, H. Brinkhiris5, A.W. Burger6, H.B. Vonhof7, K. Post8, K. Hoedemakers9, A.C. Janse10 & N. Taverne11 1 Laboratory of Genetics, Wageningen University, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD Wageningen, the Netherlands. 2 Prinsenweer 54, 3363 JK Sliedrecht, the Netherlands. 3 Naturalis, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands. 4 TN0 B&0 - National Geological Survey, P.O. Box 80015, 3508 TA Utrecht, the Netherlands. 5 Palaeocecology, Inst. Environmental Biology, Laboratory of Palaeobotany and Palynology, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, the Netherlands. 6 P. Soutmanlaan 18, 1701 MC Heerhugowaard, the Netherlands. 7 Faculty Earth and Life Sciences, Vrije Universiteit, de Boelelaan 1085, 1081 EH Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 8 Natuurmuseum Rotterdam, P.O. Box 23452, 3001 KL Rotterdam, the Netherlands. 9 Minervastraat 23, B 2640 Mortsel, Belgium. 10 Gerard van Voornestraat 165, 3232 BE Brielle, the Netherlands. 11 Snipweg 14, 5451 VP Mill, the Netherlands. * corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: February 2007; accepted: March 2008 Abstract The locality of Langenboom (eastern Noord-Brabant, the Netherlands), also known as Mill, is famous for its Neogene molluscs, shark teeth, teleost remains, birds and marine mammals. The stratigraphic context of the fossils, which have been collected from sand suppletions, was hitherto poorly understood. Here we report on a section which has been sampled by divers in the adjacent flooded sandpit 'De Kuilen' from which the Langenboom sands have been extracted. -

Marine Climate and Hydrography of the Coralline Crag (Early Pliocene, UK): Isotopic Evidence from 16 Benthic Invertebrate Taxa

Marine climate and hydrography of the Coralline Crag (early Pliocene, UK): isotopic evidence from 16 benthic invertebrate taxa. Item Type Article; Research Report Authors Vignols, Rebecca M.; Valentine, Annemarie M.; Finlayson, Alana G.; Harper, Elizabeth M.; Schöne, Bernd R.; Leng, Melanie J.; Sloane, Hilary J.; Johnson, Andrew L. A. Citation Bradshaw, J. et al. (2018). Marine climate and hydrography of the Coralline Crag (early Pliocene, UK): isotopic evidence from 16 benthic invertebrate taxa. Available at: https:// www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0009254118302717? via%3Dihub (Accessed: 22 Jan 2019). DOI: 10.1016/ j.chemgeo.2018.05.034 DOI 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2018.05.034 Publisher Elsevier Journal Chemical Geology Rights Archived with thanks to Chemical Geology Download date 06/10/2021 07:06:31 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/623343 Chemical Geology xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemical Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chemgeo Marine climate and hydrography of the Coralline Crag (early Pliocene, UK): isotopic evidence from 16 benthic invertebrate taxa Rebecca M. Vignolsa,1, Annemarie M. Valentineb,2, Alana G. Finlaysona,3, Elizabeth M. Harpera, ⁎ Bernd R. Schönec, Melanie J. Lengd, Hilary J. Sloaned, Andrew L.A. Johnsonb, a Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, UK b School of Environmental Science, University of Derby, Kedleston Road, Derby DE22 1GB, UK -

The Sedimentology and Palaeoecology of the Westleton Member of the Norwich Crag Formation (Early Pleistocene) at Thorington, Suffolk, England

Geol. Mag. 136 (4), 1999, pp. 453–464. Printed in the United Kingdom © 1999 Cambridge University Press 453 The sedimentology and palaeoecology of the Westleton Member of the Norwich Crag Formation (Early Pleistocene) at Thorington, Suffolk, England A.E. RICHARDS*, P.L. GIBBARD & M. E. PETTIT *School of Geography, Kingston University, Penrhyn Road, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, KT1 2EE, UK Godwin Institute of Quaternary Research, Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, UK (Received 28 September 1998; accepted 29 March 1999) Abstract – Extensive sections in the Thorington gravel quarry complex in eastern Suffolk include the most complete record to date of sedimentary environments of the Westleton Beds Member of the Norwich Crag Formation. New palaeoecological and palaeomagnetic evidence is presented, which confirms that the Member was deposited at or near a gravelly shoreline of the Crag Sea as sea level fluctuated during a climatic ameloriation within or at the end of the Baventian/ pre-Pastonian ‘a’ Stage (Tiglian C4c Substage). 1. Introduction 2. Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene deposits in Suffolk The gravel quarry complex at Thorington (TM 423 728) is situated 8 km west of Southwold in northern A stratigraphical table, comparing British nomencla- Suffolk (Fig. 1). This paper will present details of ture with that of the Netherlands, is given in Table 1. observations in the quarry during the period from The earliest Pleistocene deposits that occur in June 1994 to September 1997, which provide signifi- northern Suffolk are the East Anglian Crags, which cant biostratigraphical and sedimentological evidence were deposited at the margins of the southern North for depositional environments associated with the Sea Basin. -

Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning

Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning Suffolk Commissioned Report CR/03/076N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY COMMISSIONED REPORT CR/03/076N Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning Suffolk D J Harrison, P J Henney, S J Mathers, D G Cameron, N A Spencer, S F Hobbs, D J Evans, G K Lott and D E Highley The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Suffolk, mineral resources, mineral planning. Front cover Front cover photo: Coastal scenery at Minsmere RSPB reserve, north of Sizewell, Suffolk. Bibliographical reference D J Harrison, P J Henney, D G Cameron, Mathers S J, N A Spencer, S F Hobbs, D J Evans, G K Lott and D E Highley. 2003. Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning. Suffolk. British Geological Survey Commissioned Report, CR/03/076N. Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2003 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. -

Pliocene Dinoflagellate Cyst Stratigraphy, Palaeoecology And

Geol. Mag.: page 1 of 21. c 2008 Cambridge University Press 1 doi:10.1017/S0016756808005438 Pliocene dinoflagellate cyst stratigraphy, palaeoecology and sequence stratigraphy of the Tunnel-Canal Dock, Belgium STIJN DE SCHEPPER∗,MARTINJ.HEAD† & STEPHEN LOUWYE‡ ∗Cambridge Quaternary, Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, UK †Department of Earth Sciences, Brock University, 500 Glenridge Avenue, St. Catharines, Ontario L2S 3A1, Canada ‡Palaeontology Research Unit, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281 – S8, B-9000 Gent, Belgium (Received 21 November 2007; accepted 8 April 2008) Abstract – Dinoflagellate cysts and sequence stratigraphy are used to date accurately the Tunnel-Canal Dock section, which contains the most complete record of marine Pliocene deposits in the Antwerp harbour area. The Zanclean Kattendijk Formation was deposited between 5.0 and 4.4 Ma during warm- temperate conditions on a shelf influenced by open-marine waters. The overlying Lillo Formation is divided into four members. The lowest is the Luchtbal Sands Member, estimated to have been deposited between 3.71 and 3.21 Ma, under cooler conditions but with an open-water influence. The Oorderen Sands, Kruisschans Sands and Merksem Sands members of the Lillo Formation are considered a single depositional sequence, and biostratigraphically dated between 3.71 and c. 2.6 Ma, with the Oorderen Sands Member no younger than 2.72–2.74 Ma. Warm-temperate conditions had returned, but a cooling event is noted within the Oorderen Sands Member. Shoaling of the depositional environment is also evidenced, with the transgressive Oorderen Sands Member passing upwards into (near-)coastal high- stand deposits of the Kruisschans Sands and Merksem Sands members, as accommodation space decreased. -

English Nature Research Report

Yatural Area: 23. Lincolnshire Marsh and Geological Significance: Notable Coast (provisional) General geological character: The solid geology of the Lincolnshire Marsh and Coast Natural Area is bminated by Cretaceous chalk (approximately 97-83 Ma) although the later Quaternary deposits (the last 2 Ma) give thc area its overall. charactcr. 'The chalk is only well exposed on thc south bank of the Humber, where quarries and cuttings providc exposures of the Upper Cretaceous Chalk. 'me chalk is a very pure limestone deposited on the floor of a tropical sea. During Quaternary timcs, the area was glaciated on several occasions and as a result the area is covered by a variety of glacial deposits, representing an unknown number of glacial ('lcc Age') and interglacial phases. rhe glacial deposits consist mainly of sands, gravels and clays in variable thicknesses. These are derived primarily from the erosion of surrounding bedrock and therefore tend to have similar lithological characteristics, usually with a high chalk content. The glacial deposits are particularly important because of the controversy surrounding their correlation with the timing and sequence in other parts of England, especially East Anglia. The Quaternary deposits are well exposed in coastal cliffs of the area. Key geological features: Coastal cliffs consisting of glacial sands, gravels and clays Exposures of Cretaceous chalk Number of GCR sites: Oxfordian: 1 Kimmeridgian: I Aptian-Rlbian: i Quaternary of Eastern England: 1 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~ ~ ~ ~~ GeologicaVgeomorphological SSSI coverage: 'here are 2 (P)SSSIs in the Natural Area covering 4 GCR SlLs which represent 4 different GCR networks. The site coverage includes South Ferriby Chalk Pit SSSI which contains an important Upper Jurassic succession, overlain by Cretaceous deposits. -

The Crags of Sutton Knoll, Suffolk in Attendance, and Jenny Quilter Unveiled the Panel

for over 170 years, and Roger Dixon, treasurer of REPORT GeoSuffolk, explained his own researches. Guy and Jenny Quilter, owners of the Sutton Hall Estate, were The Crags of Sutton Knoll, Suffolk in attendance, and Jenny Quilter unveiled the panel. The SSSI at Sutton Knoll (TM305441), also known Roger Dixon also showed us a painting of the site as as Rockhall Wood, southeast of Woodbridge, reveals it would have appeared in Red Crag times, painted by excellent exposures of a fascinating aspect of the A-level art student Louis Wood, and this could well be Neogene Crags of East Anglia. Here the Coralline Crag, used in a future explanatory panel. about 3.75 Ma in age, forms an upstanding hill, while After the ceremony, Roger Dixon led a walk around the later Red Crag, about 2.5 Ma in age, can be seen the site exposures. These reveal the Ramsholt and lapping over the Coralline Crag around the sides of the Sudbourne members of the Coralline Crag Formation, inlier. Prestwich (1871a,b) is the classic description, and the overlapping Red Crag Formation. The London while Boswell (1928) wrote the Geological Survey Clay lies at shallow depth but is not now exposed. The memoir of the Woodbridge area. Later descriptions are visible exposures are mostly old pits dug to extract given by Balson and Long (1988), Balson et al (1990), Coralline Crag to improve and repair farm tracks. One Balson (1999) and Wood (2000), and Dixon (2006, pit had been dug in 1860 to extract phosphate nodules 2007) describes recent developments. -

Journal of the Geological Society

Accepted Manuscript Journal of the Geological Society Where does the time go? Assessing the chronostratigraphic fidelity of sedimentary rock outcrops in the Pliocene- Pleistocene Red Crag Formation, eastern England Neil S. Davies, Anthony P. Shillito & William J. McMahon DOI: https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2019-056 Received 29 March 2019 Revised 24 June 2019 Accepted 28 June 2019 © 2019 The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Published by The Geological Society of London. Publishing disclaimer: www.geolsoc.org.uk/pub_ethics Supplementary material at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4561001 To cite this article, please follow the guidance at http://www.geolsoc.org.uk/onlinefirst#cit_journal Manuscript version: Accepted Manuscript This is a PDF of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting and correction before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Although reasonable efforts have been made to obtain all necessary permissions from third parties to include their copyrighted content within this article, their full citation and copyright line may not be present in this Accepted Manuscript version. Before using any content from this article, please refer to the Version of Record once published for full citation and copyright details, as permissions may be required. Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/jgs/article-pdf/doi/10.1144/jgs2019-056/4791669/jgs2019-056.pdf by guest on 25 July 2019 Where does the time go? Assessing the chronostratigraphic fidelity of sedimentary rock outcrops in the Pliocene-Pleistocene Red Crag Formation, eastern England Neil S. -

Ediacaran Life Close to Land: Coastal and Shoreface Habitats of the Ediacaran Macrobiota, the Central Flinders Ranges, South Australia

Journal of Sedimentary Research, 2020, v. 90, 1463–1499 Research Article DOI: 10.2110/jsr.2020.029 EDIACARAN LIFE CLOSE TO LAND: COASTAL AND SHOREFACE HABITATS OF THE EDIACARAN MACROBIOTA, THE CENTRAL FLINDERS RANGES, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 1 2 2 1 WILLIAM J. MCMAHON,* ALEXANDER G. LIU, BENJAMIN H. TINDAL, AND MAARTEN G. KLEINHANS 1Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Princetonlaan 8a, 3584 CB, Utrecht, The Netherlands 2Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, U.K. [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Rawnsley Quartzite of South Australia hosts some of the world’s most diverse Ediacaran macrofossil assemblages, with many of the constituent taxa interpreted as early representatives of metazoan clades. Globally, a link has been recognized between the taxonomic composition of individual Ediacaran bedding-plane assemblages and specific sedimentary facies. Thorough characterization of fossil-bearing facies is thus of fundamental importance for reconstructing the precise environments and ecosystems in which early animals thrived and radiated, and distinguishing between environmental and evolutionary controls on taxon distribution. This study refines the paleoenvironmental interpretations of the Rawnsley Quartzite (Ediacara Member and upper Rawnsley Quartzite). Our analysis suggests that previously inferred water depths for fossil-bearing facies are overestimations. In the central regions of the outcrop belt, rather than shelf and submarine canyon environments below maximum (storm-weather) wave base, -

Ice-Rafted Erratics with Early Middle Pleistocene Shallow Marine

Published in Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association (2011) Possible ice-rafted erratics in late Early to early Middle Pleistocene shallow marine and coastal deposits in northeast Norfolk, UK. Nigel R. Larkina*, Jonathan R. Leeb & E. Rodger Connellc a The Natural History Department, Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service, Shirehall, Market Avenue, Norwich, Norfolk NR1 3JQ, UK [email protected] b British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG, UK [email protected] c Geography and Environment, School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, St Mary’s, Elphinstone Road, Aberdeen, AB24 3UF UK [email protected] *Corresponding author: email [email protected] telephone 07973 869613 Abstract Erratic clasts with a mass of up to 15 kg are described from preglacial shallow marine deposits (Wroxham Crag Formation) in northeast Norfolk. Detailed examination of their petrology has enabled them to be provenanced to northern Britain and southern Norway. Their clustered occurrence in coastal sediments in Norfolk is believed to be the product of ice-rafting from glacier incursions into the North Sea from eastern Scotland and southern Norway, and their subsequent grounding and melting within coastal areas of what is now north Norfolk. The precise timing of these restricted glaciations is difficult to determine. However, the relationship of the erratics to the biostratigraphic record and the first major expansion of ice into the North Sea suggest these events occurred during at least one glaciation between the late Early Pleistocene and early Middle Pleistocene (c. 1.1−0.6 Ma). In contrast to the late Middle (Anglian) and Late Pleistocene (Last Glacial Maximum) glaciations, where the North Sea was largely devoid of extensive marine conditions, the presence of far-travelled ice-rafted materials implies that earlier cold stage sea-levels were considerably higher. -

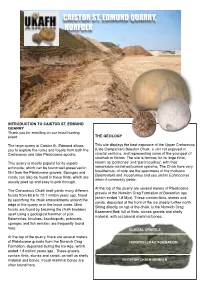

Caistor St Edmund Quarry Are Echinoids, Molluscs, Sponges and Other Fosssils Associated with the Chalk

CAISTOR ST. EDMUND QUARRY, NORFOLK INTRODUCTION TO CAISTOR ST. EDMUND QUARRY Thank you for enrolling on our fossil hunting event. THE GEOLOGY The large quarry at Caistor St. Edmund allows This site displays the best exposure of the Upper Cretaceous you to explore the rocks and fossils from both the (Late Campanian) Beeston Chalk, a unit not exposed in Cretaceous and later Pleistocene epochs. coastal sections, and representing some of the youngest of situchalk in Britain. The site is famous for its large flints, This quarry is mostly popular for its superb known as ‘potstones’ and ‘paramoudras’, with their echinoids, which can be found well-preserved in remarkable contained burrow systems. The Chalk here very flint from the Pleistocene gravels. Sponges and fossiliferous; of note are the specimens of the molluscs Belemnitella and Inoceramus and sea urchin Echinocorys corals can also be found in these flints, which are which it commonly yields. usually piled up and easy to pick through. At the top of the quarry are several meters of Pleistocene The Cretaceous Chalk itself yields many different gravels of the Norwich Crag Formation of Baventian age fossils from 83.6 to 72.1 million years ago, found (which ended 1.8 Mya). These contain flints, stones and by searching the chalk embankments around the sands, deposited at the front of the ice sheets further north. edge of the quarry or in the loose scree. Most Sitting directly on top of the chalk, is the Norwich Crag fossils are found by breaking the chalk boulders Basement Bed; full of flints, stones gravels and shelly apart using a geological hammer or pick.