Edinburgh Castle – Great Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 4 | JanUaRy - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE CHANGING STATUS OF LAWN TENIS Dr. Ganesh Narayanrao Kadam Asst. Prof. College Of Agriculture Naigaon Bz. Dist. Nanded. ABSTRACT : Tennis is a racket sport that can be played independently against a solitary adversary (singles) or between two groups of two players each (copies). Every player utilizes a tennis racket that is hung with rope to strike an empty elastic ball secured with felt over or around a net and into the rival's court. The object of the diversion is to move the ball so that the rival can't play a legitimate return. The player who can't restore the ball won't pick up a point, while the contrary player will. KEYWORDS : solitary adversary , dimensions of society , Tennis. INTRODUCTION Tennis is an Olympic game and is played at all dimensions of society and at all ages. The game can be played by any individual who can hold a racket, including wheelchair clients. The advanced round of tennis started in Birmingham, England, in the late nineteenth century as grass tennis.[1] It had close associations both to different field (garden) amusements, for example, croquet and bowls just as to the more established racket sport today called genuine tennis. Amid the majority of the nineteenth century, actually, the term tennis alluded to genuine tennis, not grass tennis: for instance, in Disraeli's epic Sybil (1845), Lord Eugene De Vere reports that he will "go down to Hampton Court and play tennis. -

TTP-Wedding-Brochure.Pdf

Weddings Contents 01 About Two Temple Place 02 Lower Gallery 03 Great Hall 04 Library 05 Upper Gallery 06 Capacities & Floorplans 07 Our Suppliers 08 Information 09 Contact Us 01 About Two Temple Place Exclusively yours for the most memorable day of your life. Two Temple Place is a hidden gem of Victorian architecture and design, and one of London’s best-kept secrets. Commissioned by William Waldorf Astor for his London office and pied-a-terre in 1895, this fully-licensed, riverside mansion is now one of London’s most intriguing and elegant wedding venues. Say `I do’ in one of our three licensed ceremony rooms and enjoy every aspect of your big day, from ceremony to wedding breakfast and dancing all under one roof. Sip champagne in Astor’s private Library; surprise your guests with a journey through our secret door; dine in splendour in the majestic Great Hall or dance the night away in the grand Lower Gallery. With a beautiful garden forecourt which acts as a suntrap in the summer months for celebratory drinks and canapés, whatever the time of year Two Temple Place is endlessly flexible and packed with individual charm and character. Let our dedicated Events team and our experienced approved suppliers guide you through every aspect of the planning process, ensuring an unforgettable day for you and your guests. All funds generated from the hire of Two Temple Place support the philanthropic mission of The Bulldog Trust, registered charity 1123081. 02 Lower Gallery Walk down the aisle in the Lower Gallery with its high ceilings and stunning wood panelling as sunlight streams through the large ornate windows. -

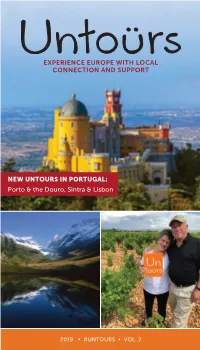

Experience Europe with Local Connection and Support

EXPERIENCE EUROPE WITH LOCAL CONNECTION AND SUPPORT NEW UNTOURS IN PORTUGAL: Porto & the Douro, Sintra & Lisbon 2019 • #UNTOURS • VOL. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS UNTOURS & VENTURES ICELAND PORTUGAL Ventures Cruises ......................................25 NEW, Sintra .....................................................6 SWITZERLAND NEW, Porto ..................................................... 7 Heartland & Oberland ..................... 26-27 SPAIN GERMANY Barcelona ........................................................8 The Rhine ..................................................28 Andalusia .........................................................9 The Castle .................................................29 ITALY Rhine & Danube River Cruises ............. 30 Tuscany ......................................................10 HOLLAND Umbria ....................................................... 11 Leiden ............................................................ 31 Venice ........................................................ 12 AUSTRIA Florence .................................................... 13 Salzburg .....................................................32 Rome..........................................................14 Vienna ........................................................33 Amalfi Coast ............................................. 15 EASTERN EUROPE FRANCE Prague ........................................................34 Provence ...................................................16 Budapest ...................................................35 -

Location, Location, Location by Pam Horack Page 15

Nancy Drew: Location, Location, Location by Pam Horack Page 15 Nancy’s World (to me) In real estate, the mantra is “Location, Location, Location”. As in a story, the right setting can be an effective plot device and can be used to evoke specific feelings. The Nancy Drew books often used a location to create the backdrop for the mysterious and adventurous. As a child, I was able to use my grandparents’ home as a true reference for many of the Nancy Drew settings, thus bringing the stories to life and turning me into Nancy Drew Green’s Folly, located in Halifax County, Virginia, was home to my maternal grandparents. As my mother was raised there, our family visited frequently. The estate has served many functions through the years: county courthouse, a racetrack, a farm, and currently an 18-hole golf course, which was originally developed by my grandfather, John G. Patterson, Jr. As a child with a vivid imagination, my senses were aroused by mysterious features of the old home. This was the world of my childhood and it made a natural location for many of my adventures with Nancy Drew. As many of the Nancy Drew stories involved large old estates, my mind easily substituted the real world for the fictitious. There seemed to be too many coincidences and similarities for it to be otherwise. I found my imagination using Green’s Folly as the backdrop for the following stories: 1. The Hidden Staircase 2. The Mystery at Lilac Inn 3. The Sign of the Twisted Candles 4. -

Falkland Palace Teacher’S Information

Falkland Palace Teacher’s information Falkland Palace was a country residence of the Stewart kings and queens. The palace was used as a lodge when the royal family hunted deer and wild boar in the forests of Fife. Mary, Queen of Scots, spent some of the happiest days of her life here ‘playing the country girl in the woods and parks’. Built between 1501 and 1541 by James IV and James V, Falkland Palace replaced earlier castle and palace buildings dating from the 12th century. The roofed south range contains the Chapel Royal, and the East Range contains the King’s and Queen’s rooms, both restored by the Trust with period features, reproduction 16th-century furnishings, painted ceilings and royal arms. Within the grounds is the original Royal tennis court, the oldest in Britain, built in 1539. The garden, designed and built by Percy Cane between 1947 and 1952, contains herbaceous borders enclosing an attractive wide lawn with many varieties of shrubs and trees and a small herb garden. The palace still belongs to Her Majesty the Queen but is maintained and managed by The Trust in its role as Deputy Keeper. A school visit to Falkland Palace offers excellent opportunities for cross-curricular work and engaging with the Curriculum for Excellence: • An exciting Living History programme, based on the visits of Mary Queen of Scots to Falkland Palace around 1565, led by NTS staff: - a tour of the palace when your pupils will meet ‘Mary Queen of Scots’. - costumes and role play (within the palace tour). - followed by an opportunity to explore the gardens and real tennis court (teacher led). -

George Washington Wilson (1823-1893)

George Washington Wilson (1823-1893) Photographically innovative and entrepreneurial in business, Wilson was the most notable, successful and prolific stereo-photographer in Scotland and perhaps the entire UK. Having trained in Edinburgh as an artist, he worked as a miniature portrait painter and art teacher in Aberdeen from 1848. He started experimenting with photography in 1852, probably realising that it could potentially supplant his previous profession. In a short-lived partnership with Hay, he first exhibited stereoviews in 1853 at the Aberdeen Mechanics' Institution. A commission to photograph the construction of Balmoral Castle in 1854-55 led to a long royal association. His photos were used in the form of engravings for Queen Victoria's popular book “My Highland Journal”. His best-selling carte-de-visite of her on a pony held by Brown (judiciously cropped to remove other superfluous retainers) fuelled the gossip surrounding this relationship. His portrait studio in Aberdeen provided steady cashflow and in 1857, to promote his studio, he produced a print grouping together famous Aberdonians, one of the earliest ever examples of a photo-collage. He soon recognised that stereoviews were the key to prosperity and by 1863 had a catalogue of over 400 views from all across the UK, selling them in a wide variety of outlets including railway kiosks and inside cathedrals. His artistic training helped him compose picturesque and beautiful images, but he was also an innovative technician, experimenting on improving photographic techniques, chemistry and apparatus, working closely with camera and lens manufacturers. He was among the very first to publish “instantaneous” views, ranging from a bustling Princes Street, Edinburgh to a charming view of children paddling in the sea, both dating from 1859. -

The Great Hall of BMA House

Br Med J (Clin Res Ed): first published as 10.1136/bmj.289.6460.1738 on 22 December 1984. Downloaded from 1738 BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 289 22-29 DECEMBER 1984 The Great Hall of BMA House Since last August the Great Hall at BMA has been undergoing reconstruction that will eventually turn the lower part into a new library and the upper part into a suite ofcommittee rooms (see "BMJ" 5 November 1983, p 1367). The scheme has been drawn up by the BMA's architect, Ivan Nellist, who talked to7ane Smith, a "BMJ" staffeditor, about the scheme and its progress. JANE SMITH: What do you think of Lutyens's work? the needs of the user and the nature of the building. At its simplest IVAN NELLIST: I admire it. Viewed from the outside much of it is you might think that several floors of offices could have been extremely fine, but on the inside it often leaves a lot to be desired "slotted in" to the Great Hall. That would not have been very for the users-mainly because he designed on such a monumental successful, even if the structure had been strong enough to take scale. Although some of the interior spaces are excellent, in others several floors. For example, the edges of floors would have you find unaccountable things: bits where you go upstairs and appeared against the very large windows overlooking the courtyard downstairs again, dead ends, and so on. -hardly a happy solution. SMITH: So what challenges did these problems present when you So the type of solution we have adopted is probably the best. -

Falkland Palace

CSG Annual Conference - Stirling - April 2013 - Falkland Palace 24 THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL NO 27: 2013-14 CSG Annual Conference - Stirling - April 2013 - Falkland Palace Falkland Palace. The High St/ East Port is dominated by the imposing south front and its French influenced gatehouse. Previous Page: Engraving by David Roberts (1796-1864). It draws on the Romantic atmosphere of the palace during its years of decline. The original hangs in the Keeper’s Dressing Room in the palace. Falkland Palace, Fife (1500-13 James IV, 1537-42 quarter) is the three storey gatehouse (1539-41) James V) is a former royal palace of the Scottish similar in style to the north-west tower of the Palace kings. It was a hunting palace, more a place to relax of Holyroodhouse. The pend entrance is sand- than a place of State. The Scottish Crown acquired wiched between large round towers, crenellated, Falkland Castle from MacDuff of Fife in the 14th with a chemin de ronde and conical roofs. The rest century. Today It is a cluster of architectural gems of the south range (1511-13) is a fusion of styles. difficult to categorise - built in a mixture of styles - On the south side - the street frontage - vertical Gothic, Baronial, Franco -Scottish with Italianate Gothic blends with Renaissance. Niched buttresses overtones. In short, it’s a Renaissance masterpiece. intersect string courses and an elaborately corbelled Today it is an L-shaped, two-sided building, with parapet. The rear courtyard facade of the lean-to the foundations of a third side (the Great Hall) to the corridor, refaced in 1537-42 has finely detailed north which was burnt by Cromwell’s troops in buttresses of Corinthian columns. -

The Book M: Or Masonry Triumphant by William Smith 1736 Transcribed and Edited by R.’.W.’

The Book M: or Masonry Triumphant by William Smith 1736 Transcribed and Edited by R.’.W.’. Gary L. Heinmiller Director, Onondaga & Oswego Masonic Districts Historical Societies [OMDHS] www.omdhs.syracusemasons.com April 2012 Leonard Umfreville, Printer - b. 23 Dec 1702; d. 9 Mar 1737 was the third son of Captain Thomas Umfreville. He was an established printer in Newcastle and in 1734 published the ‘North Country Journal or Impartial Register’ in 1734. Leonard is also known as the writer of ‘The book M or Masonry Triumphant’, this was in the very early days of Freemasonry and it is very unlikely that he wasn’t a freemason in order to write such a book. He passed on the business to his brother Thomas suggesting that he had no heirs. An . early printer in Newcastle was Leonard Umfreville (son of an officer in the army), who preceded Thompson and Co. in the establishment of a newspaper. He began the North-Country Journal, or Impartial Register, in the year 1734; and, dying on the 9th of March, 1737, his son Thomas succeeded him in the business, but gave it up in favour of the parish clerkship of St. John's, which he held for about forty years, or, in other words, till his death at the end of June, 1783. Leonard Umfreville, who founded this short- lived newspaper, was not only a vendor of books, but an author also, having given to the world "The Book M, or Masonry Triumphant," a mystic volume of which there was a rare copy in the library of the late Mr. -

Following the Sacred Steps of St. Cuthbert

Folowing te Sacred Stps of St. Cutbert wit Fater Bruce H. Bonner Dats: April 24 – May 5, 2018 10 OVERNIGHT STAYS YOUR TOUR INCLUDES Overnight Flight Round-trip airfare & bus transfers Edinburgh 3 nights 10 nights in handpicked 3-4 star, centrally located hotels Durham 2 nights Buffet breakfast daily, 4 three-course dinners Oxford 2 nights Expert Tour Director London 3 nights Private deluxe motorcoach DAY 1: 4/24/2018 TRAVEL DAY Board your overnight flight to Edinburgh today. DAY 2: 4/25/2018 ARRIVAL IN EDINBURGH Welcome to Scotland! Transfer to your hotel and get settled in before meeting your group at tonight’s welcome dinner. Included meals: dinner Overnight in Edinburgh DAY 3: 4/26/2018 SIGHTSEEING TOUR OF EDINBURGH Get to know Edinburgh in all its medieval beauty on a tour led by a local expert. • View the elegant Georgian-style New Town and the Royal Mile, two UNESCO World Heritage sites • See the King George statue and Bute House, the official residence of the Scottish Prime Minister • Pass the Sir Walter Scott monument • Enter Edinburgh Castle to view the Scottish crown jewels and Stone of Scone Enjoy a free afternoon in Edinburgh to explore the city further on your own. Included Entrance Fees: Edinburgh Castle Included meals: breakfast Overnight in Edinburgh DAY 4: 4/27/2018 STIRLING CASTLE AND WILLIAM WALLACE MONUMENT Visit Stirling, a town steeped in the history of the Wars of Scottish Independence. For generations, Sterling Castle held off British advances and served as a rallying point for rebellious Scots. It was within Stirling Castle that the infant Mary Stewart was crowned Mary, Queen of Scots. -

Scotland ~ Stirling

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 28 Travele rs JO URNEY Scotland ~ Stirling Inspiring Moments >Revel in the pageantry of the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo. >Admire the captivating beauty of Loch Lomond and The Trossachs INCLUDED FEATURES National Park in the Highlands. >Meet a kilt maker and bagpiper to Accommodations Itinerary (with baggage handling) Day 1 Depart gateway city A learn about these vibrant traditions. – 7 nights in Stirling, Scotland, at the Day 2 Arrive in Edinburgh | Transfer A >Marvel at majestic Edinburgh Castle. Stirling Highland Hotel, a first-class to Stirling >Witness St Andrews’ gems — its hotel. Day 3 Stirling cathedral, castle and the Old Course, Extensive Meal Program Day 4 Luss | Loch Lomond and The golf’s home. – 7 breakfasts, 4 lunches and 4 dinners, Trossachs >Take in commanding vistas from the including Welcome and Farewell Day 5 St Andrews ramparts of Stirling Castle. Dinners; tea or coffee with all meals, Day 6 Edinburgh > plus wine with dinner. Experience a haggis ceremony and Day 7 Perth | Crieff relish a joyful ceilidh, a party filled – Opportunities to sample authentic Day 8 Stirling with folk music and dancing. cuisine and local flavors. Day 9 Transfer to Edinburgh | Depart Your One-of-a-Kind Journey for gateway city A Stirling Castle – Discovery excursions highlight ATransfers and flights included for AHI FlexAir participants. the local culture, heritage and history. Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Walking is required on many excursions. enhance your insight into the region. – AHI Connects: Local immersion. – Free time to pursue your own interests. -

Denver International Airport Breaks Ground on Phase 2 of the Great Hall Project

[email protected] 24/hr. Media Line: 720-583-5758 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Denver International Airport Breaks Ground on Phase 2 of the Great Hall Project DENVER – July 7, 2021 – Today, Denver International Airport (DEN) Chief Executive Officer Kim Day was joined by Alan Salazar, Chief of Staff for Mayor Michael B. Hancock; Larry Nau, TSA Federal Security Director, Colorado; and Derek Hoffine, Hensel Phelps Vice President and District Manager for a groundbreaking ceremony for Phase 2 of the Great Hall Project. The primary focus of Phase 2 is to enhance security by building a new security checkpoint on Level 6 in the northwest corner of the Jeppesen Terminal. “The new security checkpoint will have improved technology and a new queuing concept that will provide more effective and efficient security,” said Day. “These improvements combined with the new ticketing pods being constructed as part of Phase 1 will ultimately allow us to build a terminal for the future with enhanced security, increased capacity, improved operational efficiency and an elevated passenger experience.” All Phase 2 work will be done in in mid-2024. However, the new checkpoint is scheduled to open by early 2024. Passengers will then have access to the new checkpoint on Level 6 as well as the north checkpoint and the existing A-bridge checkpoint. Additionally, the new checkpoint on Level 6 creates a future opportunity to activate the vacated south security space on Level 5 with new concessions and improved meeter/greeter amenities. “As DEN continues to grow, it is critical that we invest in the airport and prepare for the future.