Forestry Commission Journal No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026

North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026 North Highland Forest District North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016 - 2026 Plan Reference No:030/516/402 Plan Approval Date:__________ Plan Expiry Date:____________ | North Sutherland LMP | NHFD Planning | North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026 Contents 4.0 Analysis and Concept 4.1 Analysis of opportunities I. Background information 4.2 Concept Development 4.3 Analysis and concept table 1.0 Introduction: Map(s) 4 - Analysis and concept map 4.4. Land Management Plan brief 1.1 Setting and context 1.2 History of the plan II. Land Management Plan Proposals Map 1 - Location and context map Map 2 - Key features – Forest and water map 5.0. Summary of proposals Map 3 - Key features – Environment map 2.0 Analysis of previous plan 5.1 Forest stand management 5.1.1 Clear felling 3.0 Background information 5.1.2 Thinning 3.1 Physical site factors 5.1.3 LISS 3.1.1 Geology Soils and landform 5.1.4 New planting 3.1.2 Water 5.2 Future habitats and species 3.1.2.1 Loch Shin 5.3 Restructuring 3.1.2.2 Flood risk 5.3.1 Peatland restoration 3.1.2.3 Loch Beannach Drinking Water Protected Area (DWPA) 5.4 Management of open land 3.1.3 Climate 5.5 Deer management 3.2 Biodiversity and Heritage Features 6.0. Detailed proposals 3.2.1 Designated sites 3.2.2 Cultural heritage 6.1 CSM6 Form(s) 3.3 The existing forest: 6.2 Coupe summary 3.3.1 Age structure, species and yield class Map(s) 5 – Management coupes (felling) maps 3.3.2 Site Capability Map(s) 6 – Future habitat maps 3.3.3 Access Map(s) 7 – Planned -

Item 10: Kielder Water & Forest Park Development Trust

Item 10: Kielder Water & Forest Park Development Trust - Report on First Year’s Membership Item 10 : KIELDER WATER & FOREST PARK DEVELOPMENT TRUST – REPORT ON FIRST YEAR’S MEMBERSHIP Purpose of Report a. To update members on the Authority’s membership of the Kielder Water & Forest Park Development Trust (KWFPDT) and related achievements. 2. Recommendations a. Members are asked to note the achievements through the Authority’s involvement in the KWFPDT and endorse the Authority’s ongoing membership of the partnership. 3. Implications a. Financial There are no additional financial implications. The Authority previously agreed an annual partnership contribution of £10,000, which is allowed for in the medium term financial plan. b. Equalities None 4. Background a. In September 2016 the Authority agreed to accept the invitation to become a member of the KWFPDT. This followed a period of close partnership working through the International Dark Sky Park and opportunities emerging through The Sill and the Border Uplands Demonstrator Initiative (BUDI). 5. Progress In August 2017, Tony Gates and John Riddle took up roles as Directors of KWFPDT on behalf of NNPA. This report covers activity over the past year. KWFPDT has had a successful and productive year, welcoming approximately 410,000 visitors to the Park as a whole and generating in the region of £24million for the wider local economy, including the North Tyne and Redesdale. Wildlife Tourism a) Living Wild at Kielder In October the Trust secured a £336,300 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund towards a £½million two year partnership project to animate Kielder Water & Forest Park’s amazing wildlife for visitors and residents, helping them enjoy, learn, share and immerse themselves in nature. -

Travelling Tales Explore Kielder Forest Drive

Travelling Tales explore Kielder Forest Drive Welcome to England’s longest Use this guide to help you Please return this guide to and highest Forest Drive, which discover the secrets of our one of the toll points winds through the working forest wild border country. What at either end of the Forest will you see here today? Drive when you leave. West North East between Kielder Castle and To Kielder Water & To Scotland To Redesdale Forest Park and the Blakehopeburnhaugh on the A68. Cheviot Hills Blakehope Nick and The Nick shelter 457m above sea level Mid-point of the Forest Drive. Top of the watershed between the North Tyne and Rede river valleys. The burns Spot rocky ridges and old Watch for the white rumps flowing west feed into Kielder Water. quarries. The sandstone Height of roe deer, or glimpse was used for building. our secretive feral goats. 500m Look out for red squirrels Stroll to the wildlife and listen for the cat-like hide above Kielder call of buzzards overhead. 400m Burn, or enjoy upland meadows and a picnic near East Kielder. Blakehopeburnhaugh Waterfall trail Spot a circular stone ‘stell’ 300m for holding sheep. This area was farmed before The weather can be wild up Kielder Forest was planted. here, so the Forest Drive closes over the winter. 200m 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kielder Forest Drive 12 miles (20km) Forest Drive only open seasonally. Please check forestryengland.uk for details. Connecting communities Kielder Forest Drive opened in 1973. It was built by Forestry Kielder Castle England for planting and harvesting trees high on these hills. -

Accessing and Developing the Required Biophysical Datasets and Datalayers for Marine Protected Areas Network Planning and Wider Marine Spatial Planning Purposes

Accessing and developing the required biophysical datasets and datalayers for Marine Protected Areas network planning and wider marine spatial planning purposes Report No 8 Task 2A. Mapping of Geological and Geomorphological Features Version (Final) 27 November 2009 © Crown copyright 1 Project Title: Accessing and developing the required biophysical datasets and datalayers for Marine Protected Areas network planning and wider marine spatial planning purposes Report No 8: Task 2A. Mapping of Geological and Geomorphological Features Project Code: MB0102 Marine Biodiversity R&D Programme Defra Contract Manager: Jo Myers Funded by: Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) Marine and Fisheries Science Unit Marine Directorate Nobel House 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY Countryside Council for Wales (CCW) Maes y Ffynnon Penrhosgarnedd Bangor LL57 2DW Natural England (NE) North Minister House Peterborough PE1 1UA Scottish Government (SG) Marine Nature Conservation and Biodiversity Marine Strategy Division Room GH-93 Victoria Quay Edinburgh EH6 6QQ Department of Environment Northern Ireland (DOENI) Room 1306 River House 48 High Street Belfast BT1 2AW 2 Isle of Man Government (IOM) Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry Rose House 51-59 Circular Road Douglas Isle of Man IM1 1AZ Authorship: A. J. Brooks ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd [email protected] H. Roberts ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd [email protected] N. H. Kenyon Associate [email protected] A. J. Houghton ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd [email protected] ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd Suite B Waterside House Town Quay Southampton Hampshire SO14 2AQ www.abpmer.co.uk Disclaimer: The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the views of Defra, nor is Defra liable for the accuracy of the information provided, nor is Defra responsible for any use of the reports content. -

Comparison and Validation of Three Versions of a Forest Wind Risk Model

Environmental Modelling & Software 68 (2015) 27e41 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Modelling & Software journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envsoft Comparison and validation of three versions of a forest wind risk model * Sophie A. Hale a, Barry Gardiner a, b, c, , Andrew Peace a, Bruce Nicoll a, Philip Taylor a, d, Stefania Pizzirani a, e a Forest Research, Northern Research Station, Roslin, EH25 9SY, Scotland, UK b INRA, UMR 1391 ISPA, F-33140, Villenave d'Ornon, France c Bordeaux Sciences Agro, UMR 1391 ISPA, F-33170, Gradignan, France d Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Bush Estate, Penicuik, EH26 0QB, Scotland, UK e Scion, Te Papa Tipu Innovation Park, 49 Sala Street, Rotorua 3010, Private Bag 3020, Rotorua, 3046, New Zealand article info abstract Article history: Predicting the probability of wind damage in both natural and managed forests is important for un- Received 14 July 2014 derstanding forest ecosystem functioning, the environmental impact of storms and for forest risk Received in revised form management. We undertook a thorough validation of three versions of the hybrid-mechanistic wind risk 24 January 2015 model, ForestGALES, and a statistical logistic regression model, against observed damage in a Scottish Accepted 26 January 2015 upland conifer forest following a major storm. Statistical analysis demonstrated that increasing tree Available online height and local wind speed during the storm were the main factors associated with increased damage This paper is dedicated to the memory of levels. All models provided acceptable discrimination between damaged and undamaged forest stands Mike Raupach whose work on aerodynamic but there were trade-offs between the accuracy of the mechanistic models and model bias. -

WALKING in NORTHUMBERLAND About the Author Vivienne Is an Award-Winning Freelance Writer and Photographer Specialis- Ing in Travel and the Outdoors

WALKING IN NORTHUMBERLAND About the Author Vivienne is an award-winning freelance writer and photographer specialis- ing in travel and the outdoors. A journalist since 1990, she abandoned the WALKING IN constraints of a desk job on regional newspapers in 2001 to go travelling. On her return to the UK, she decided to focus on the activities she loves the NORTHUMBERLAND most – hill walking, writing, travelling and photography. Needless to say, she’s never looked back! Vivienne Crow Based in north Cumbria, she has put her intimate knowledge of north- ern England to good use over the years, writing more than a dozen popu- lar walking guidebooks. She also contributes to a number of regional and national magazines, including several regular walking columns, and does copywriting for conservation and tourism bodies. Vivienne is a member of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild. Other Cicerone guides by the author Walking in Cumbria’s Eden Valley Lake District: High Level and Fell Walks Lake District: Low Level and Lake Walks JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Vivienne Crow 2018 First edition 2018 CONTENTS ISBN: 978 1 85284 900 9 Replaces the previous Cicerone guide to Northumberland by Alan Hall Map key ...................................................... 7 ISBN: 978 1 85284 428 8 Overview map ................................................. 9 Second edition 2004 First edition 1998 INTRODUCTION ............................................. 11 Weather ..................................................... 12 Printed in China on behalf of Latitude Press Geology ..................................................... 13 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Wildlife and habitats ........................................... 14 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. -

Appendix 2 - Baseline Data Information and Maps

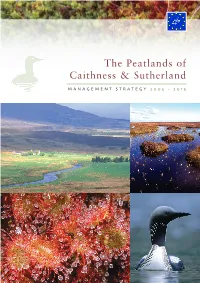

Appendix 2 - Baseline Data Information and Maps The information in this section represents baseline data which has been taken at either Highland wide level or, when available, Caithness and Sutherland level. Biodiversity, Flora and Key information Data Source Fauna Protect, enhance and There are currently 150 SSSI’s, 29 SNH website for information on where necessary restore SAC’s, 15 SPA’s, 4 NNR’s, 3 RAMSAR designated sites, site condition and designated wildlife sites in the Plan area. qualifying interests/features: and protected species www.snh.org.uk Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (Scotland’s Biodiversity - It’s In Your Hands; 2020 Challenge for Scotland’s Biodiversity) Flow Country, nominated to UNESCO The Peatlands of Caithness and as a tentative World Heritage Site, is a Sutherland - Management Strategy vitally important habitat on a regional 2005 - 2015 and international scale. It is the largest expanse of blanket bog in Europe, and covers about 4,000 km2 and home to a rich variety of wildlife, and is used as a breeding ground for many different species of birds. Improve biodiversity, Highland region supports 192 of the Highland Biodiversity Action Plan avoiding irreversible 238 priority species in Scotland and 40 www.highlandbiodiversity.com losses. of the 42 priority habitats. 455 of the priority species of conservation Habitat and Birds Directive – Annex importance are found in Highland. 1 Provide appropriate Proportion of population living within The Highland Councils Core path opportunities for people 200m of a footpath. The core paths plan. to come into contact with plan is yet to be completed but this and appreciate wild life information will be added to the and wild places. -

UK: FOREST PROFILE1 the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Located to the North-West of Continental Europe, Has a Mild, Humid Climate

UK MARKET PROFILE UNITED KINGDOM MARKET PROFILE UK: FOREST PROFILE1 The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, located to the north-west of continental Europe, has a mild, humid climate. Forest and other wooded land accounts for only one tenth of the land area; this percentage has doubled since the First World War as a result of afforestation, much of which took place in Scotland, Wales and northern England. More than four fifths of the forest is available for wood supply; the remainder is not available, for conservation and protection reasons. Over two thirds of the forest is classed as plantations, the remainder as semi-natural. Public ownership has been declining as a result of privatization, to around two fifths of the total. Most private forests are owned by individuals but some by investment groups and nature conservation associations. Britain's warm wet climate is ideal for growing trees. Historically most of the country was covered by natural forest, but by the end of World War I clearances over the past centuries had reduced the tree cover to 4%. A regulated forestry sector and a program of reforestation have increased this figure to almost 11% an area of 2.4M hectares. UK’S FOREST DISTRIBUTION Around 80% of the timber used in the U.K. is Forest Cover 2000 Distribution of land cover/use % (2000) softwood (of conifer origin). Productive conifer woodlands cover about 1.5M hectares, a large ´000 ha Forest Other Wooded Land Other land proportion of which is in Scotland. Britain also United Kingdom 2,794 11.6 .0 88.4 has Europe’s largest man-made forest at Europe 1,039,250 46.0 1.3 52.9 Kielder Forest in Northumberland. -

Better Than The

TOURING – NORTHUMBERLAND Better than the If you prefer your rugged landscapes without an outdoors shop round every bend, Northumberland is your county. Where Hadrian’s Wall marks ancient divides, you’ll find a sociable seclusion... and plenty to entertain you WORDS Gary Blake PHOTOGRAPHY Gary Blake & Wendy Johnson Cheviot Hills Kielder Water Hexham Newcastle Walking the Wall is a challenge NORTHUMBERLAND but don’t forget to simply sit and stare for a while Photo credit: istock | 48 Go caravan www.go-caravan.co.uk part of | September 2011 49 | TOURING – NORTHUMBERLAND The bustling beach at Agay BUSY DAY Forest adventure The National Park around Kielder Water (www.visitkielder.com ) has so much to offer. The Canadian-style adventure forest is home of Calvert Trust, whose outdoor adventures for disabled people include exhilarating sailing, abseiling and high wire ropes, with able-bodied friends joining in. Kielder’s forest paths goad mountain bikers to go faster n my mind, I’m in a scene from The Eagle, the Hollywood blockbuster about the Romans’ Ninth Legion, lost in Northern Britain. I’m here on the wall, marching eastbound to the Walk the wall To enjoy Hadrian’s Wall, get a free garrison of Housesteads Fort and along the iconic I Kielder Water’s Lewisburn Bay, viewed from the road. circular walk map from ‘Great Wall of China’ section of Hadrian’s wall, on the It gets even better on foot Northumberland Parks Centres. The dramatic escarpment of Steel Rigg. From the high AD 122 bus plies the Wall in summer so you can walk bits, taking in the ground of the wall, it’s easy to imagine the barbarians Vindolanda Roman Museum as (the rebellious Scottish tribes) being kept at bay by the Commission’s Kielder Water, as well as a spectacular walk Canterbury. -

Beavers in Scotland a Report to the Scottish Government Beavers in Scotland: a Report to the Scottish Government

Beavers in Scotland A Report to the Scottish Government Beavers in Scotland: A report to the Scottish Government Edited by: Martin Gaywood SNH authors (in report section order): Martin Gaywood, Andrew Stringer, Duncan Blake, Jeanette Hall, Mary Hennessy, Angus Tree, David Genney, Iain Macdonald, Athayde Tonhasca, Colin Bean, John McKinnell, Simon Cohen, Robert Raynor, Paul Watkinson, David Bale, Karen Taylor, James Scott, Sally Blyth Scottish Natural Heritage, Inverness. June 2015 ISBN 978-1-78391-363-3 Please see the acknowledgements section for details of other contributors. For more information go to www.snh.gov.uk/beavers-in-scotland or contact [email protected] Beavers in Scotland A Report to the Scottish Government Foreword Beavers in Scotland I am delighted to present this report to Scottish Ministers. It is the culmination of many years of dedicated research, investigation and discussion. The report draws on 20 years of work on beavers in Scotland, as well as experience from elsewhere in Europe and North America. It provides a comprehensive summary of existing knowledge and offers four future scenarios for beavers in Scotland for Ministers to consider. It covers a wide range of topics from beaver ecology and genetics, to beaver interactions with farming, forestry, and fisheries. The reintroduction of a species, absent for many centuries, is a very significant decision for any Government to take. To support the decision- making process we have produced this comprehensive report providing one of the most thorough assessments ever done for a species reintroduction proposal. Ian Ross Chair Scottish Natural Heritage June 2015 Commission from Scottish Ministers to SNH, January 2014 Advice on the future of beavers in Scotland SNH should deliver a report to Scottish Ministers by the end of May 2015 summarising our current knowledge about beavers and setting out a series of scenarios for the future of beavers in Scotland. -

Performing the Anglo-Scottish Border: Cultural Landscapes, Heritage and Borderland Identities

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Holt, Ysanne (2018) Performing the Anglo-Scottish Border: Cultural Landscapes, Heritage and Borderland Identities. Journal of Borderland Studies, 33 (1). pp. 53-68. ISSN 0886-5655 Published by: Taylor & Francis URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1267586 <https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1267586> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/30439/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription -

The Peatlands of Caithness & Sutherland

The Peatlands of Caithness & Sutherland MANAGEMENT STRATEGY The Peatlands of Caithness & Sutherland MANAGEMENT STRATEGY Contents # Foreword $ INTRODUCTION WHAT’S SO SPECIAL ABOUT THE PEATLANDS? $ # SO MANY TITLES % $ MANAGEMENT OF THE OPEN PEATLANDS AND ASSOCIATED LAND $ MANAGEMENT OF WOODLANDS IN AND AROUND THE PEATLANDS #$ % COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT #( ' SPREADING THE MESSAGE ABOUT THE PEATLANDS $ ( WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? $# Bibliography $$ Annex Caithness and Sutherland peatlands SAC and SPA descriptions $% Annex Conservation objectives for Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands SAC and SPA $' Acknowledgements $( Membership of LIFE Peatlands Project Steering Group $( Contact details for LIFE Peatlands Project funding partners $( Acronyms and abbreviations Bog asphodel Foreword As a boy I had the great privilege of spending my summers at Dalnawillan= our family home= deep in what is now called the “Flow Country” Growing up there it was impossible not to absorb its beauty= observe the wildlife= and develop a deep love for this fascinating and unique landscape Today we know far more about the peatlands and their importance and we continue to learn all the time As a land manager I work with others to try to preserve for future generations that which I have been able to enjoy The importance of the peatlands is now widely recognised and there are many stakeholders and agencies involved The development of this strategy is therefore both timely and welcome The peatlands of Caithness and Sutherland are a special place= a vast and