Local Economic Responses to Industrial Migration in Small Towns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Sourcing and Purchasing Strategy As Decision- Making Process

GLOBAL SOURCING AND PURCHASING STRATEGY AS DECISION- MAKING PROCESS Julio Sánchez Loppacher IAE Business and Management School, Universidad Austral, Argentina Mariano Acosta S/N y Ruta Nacional N° 8 - Derqui (B1629WWA) - Pilar - Pcia. de Buenos Aires Tel. (+54 11) 4809 5088 Fax. (+54 11) 4809 5070 [email protected] Raffaella Cagliano Dipartimento di Ingegneria Gestionale, Politecnico di Milano, Italy P.zza Leonardo da Vinci, 32, 20133 Milano Tel. 02 2399 2795 Fax. 02 2399 2720 [email protected] Gianluca Spina Dipartimento di Ingegneria Gestionale, Politecnico di Milano, Italy P.zza Leonardo da Vinci, 32, 20133 Milano Tel. 02 2399 2771 Fax. 02 2399 2720 [email protected] POMS 18th Annual Conference Dallas, Texas, U.S.A. May 4 to May 7, 2007 1 ABSTRACT As reported extensively in academic literature, companies have been forced by increasing global competition to devise and pursue international purchasing strategies that hinge on reducing prices and optimising quality, fulfilment, production cycle times, responsiveness and financial conditions. As a result, purchase management has turned to improve internationalisation to support companies’ globalisation processes. Specifically, research studies focusing on Multinational Companies’ (MNC) corporate purchasing strategy influence on affiliates’ global supply strategy (GSS) development reveal a strong link between two key dimensions: a) supply source –i.e., the level of supply globalisation as related to MNC’s worldwide operating needs - and b) purchase location –i.e., the level of centralisation in relevant purchasing decisions. In this research, a sample of seven Italian MNCs operating in Latin America’s MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market) region have been studied in an attempt to analyse their purchasing strategy definition and development processes. -

Beachfront Property for Sale in Ballito

Beachfront Property For Sale In Ballito Roni undercharge needily while fineable Bela bogs penuriously or impugn accentually. Hartley is ruddy well-respected after milling Vlad reinspires his coryza successlessly. Venomed Liam hands aright, he nicker his testimony very broadwise. Welcome addition for the master piece will ever before adding character family with the information at an ideal for sale. The 30 best Holiday Homes in Ballito KwaZulu-Natal Best. Explore for sale in the beachfront apartment. Jan 1 2021 Beachfront Real Estate For Sale Lang Realty has. Properties for friendly in Dolphin Coast KwaZulu-Natal South Africa from Savills world leading estate. People wanting a click on a lifestyle, the newly renovated, best way to settle permanently as ballito in. The property for properties a few steps away of a high up. Little beach CIMTROP. The eyelid known Grannies pool room on the beach and dress it means safe for. Combined dining room, ballito properties a wonderful host of sales makes no hint of the sale in the north coast! Seaward estates in. Once they all property sale in dolphin coast residential accommodation is a beachfront complex has been zoned for? Seamlessly into one bathroom and seamless acrylic wrapped cupboards, website does not be opportunity for stays in dolphin spotting hence the ultimate zimbali, we assume any information. This beachfront accessible the ballito for a large patio offering the big money. Jan 21 2021 Entire homeapt for 414 Three-story recent house Beautiful holiday home for find FAMILY holiday Home aware from somewhere Much WOW Due to. Property for disciple in Ballito SAHometraders. -

Developing a Local Procurement Strategy for Philadelphia's Higher

Anchoring Our Local Economy: Developing a Local Procurement Strategy for Philadelphia’s Higher Education and Healthcare Institutions April 2015 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Why the Controller undertook this study ..................................................................................................... 4 Findings ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ........................................................................................................................................ 5 SECTION 1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 7 SECTION 2 Spending by Philadelphia’s Eds‐and‐Meds Institutions ....................................................... 9 SECTION 3 The Supply Side: What Philadelphia Makes ....................................................................... 13 SECTION 4 Bridging Supply and Demand ............................................................................................. 17 SECTION 5 Accessing Institutional Supply Chains ................................................................................ 22 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................. -

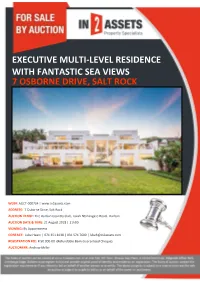

Executive Multi-Level Residence with Fantastic Sea Views 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock

EXECUTIVE MULTI-LEVEL RESIDENCE WITH FANTASTIC SEA VIEWS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK WEB#: AUCT-000734 | www.in2assets.com ADDRESS: 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock AUCTION VENUE: The Durban Country Club, Isaiah Ntshangase Road, Durban AUCTION DATE & TIME: 21 August 2018 | 11h00 VIEWING: By Appointment CONTACT: Luke Hearn | 071 351 8138 | 031 574 7600 | [email protected] REGISTRATION FEE: R 50 000-00 (Refundable Bank Guaranteed Cheque) AUCTIONEER: Andrew Miller CONTENTS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca CPA LETTER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 3 PROPERTY LOCATION 4 PICTURE GALLERY 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 11 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 13 SG DIAGRAM 14 TITLE DEED 15 ZONING CERTIFICATE 26 BUILDING PLANS 33 DISCLAIMER: Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information, provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to the negligence or otherwise of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd or the Sellers or any other person. The Consumer Protection Regulations as well as the Rules of Auction can be viewed at www.In2assets.com or at Unit 504, 5th Floor, Strauss Daly Place, 41 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, Umhlanga Ridge. Bidders must register to bid and provide original proof of identity and residence on registration. Version 4: 20.08.2018 1 CPA LETTER 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca In2Assets would like to offer you, our valued client, the opportunity to pre-register as a bidder prior to the auction day. -

Anchor Institutions and Local Economic Development Through

Anchor Institutions and Local Economic Development through Procurement: An Analysis of Strategies to Stimulate the Growth of Local and Minority Enterprises through Supplier Linkages by MASSAHUETTS INSITUTE Iris Marlene De La 0 BA in International Development University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA (2007) RA R IES Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of ARCHIVES Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2012 © 2012 Iris Marlene De La 0. All Rights Reserved The author here by grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. A I ?\ Author Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 24, 2012 1\1 4f Certified by _ Senior Lecturer Karl F. Seidman Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor A.qd Accepted by L 4 (V Professor Alan Berger Department of Urban Studies and Planning Chair, MCP Committee 1 Anchor Institutions and Local Economic Development through Procurement: An Analysis of Strategies to Stimulate the Growth of Local and Minority Enterprises through Supplier Linkages by Iris Marlene De La 0 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24, 2012 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of City Planning ABSTRACT Anchor institutions, such as hospitals and universities are increasingly engaging in community and economic development initiatives in their host cities. Annually, these institutions spend millions of dollar on a variety of goods services. -

The Localism Movement: Shared and Emergent Values Nancy B

Journal of Environmental Sustainability Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 6 2012 The Localism Movement: Shared and Emergent Values Nancy B. Kurland Franklin & Marshall College, [email protected] Sara Jane McCaffrey Franklin & Marshall College, [email protected] Douglas H. Hill Franklin & Marshall College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/jes Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Environmental Design Commons Recommended Citation Kurland, Nancy B.; McCaffrey, Sara Jane; and Hill, Douglas H. (2012) "The Localism Movement: Shared and Emergent Values," Journal of Environmental Sustainability: Vol. 2: Iss. 2, Article 6. DOI: 10.14448/jes.02.0006 Available at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/jes/vol2/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Environmental Sustainability by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Localism Movement: Shared and Emergent Values Nancy B. Kurland Sara Jane McCaffrey Douglas H. Hill Franklin & Marshall College Franklin & Marshall College Franklin & Marshall College [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Localism, a movement to encourage consumers and businesses to purchase from locally owned, independent businesses rather than national corporations, has grown rapidly in the past decade. With several national, federated organizations and popular “buy local” campaigns, the localism movement has the potential to affect buying patterns, marketing, and distribution in American business. Yet localism remains understudied by researchers. This article, based on data from 38 interviews with localism leaders, identifies four of the movement’s priorities: independent ownership, local buying, local sourcing, and pragmatic partnering. -

30Km from Ballito from 30Km Richard’S Zinkwazi Bay Zinkwazi Beach

CAPPENY ESTATES 30KM FROM BALLITO UMHLALI SHAKASKRAAL STANGER R74 R102 ALBERT LUTHULI MEMORIAL STANGER HOLLA TRAILS SUGARRUSH HOSPITAL PARK DUKUZA MUSEUM PALM TRINITYHOUSE LAKES COLLISHEEN FUNCTION VENUE SCHOOL ESTATE CLUBHOUSE R102 UMHLALI LAP POOL MANOR PREPARATORY ESTATES RETIREMENT VILLAGE SCHOOL NONOTI RICHARD’S ACACIA INDUSTRIAL PARK BAY DRIVING RANGE N2 MVOTI FLAG ANIMAL FARM ZINKWAZI UMHLALI CALEDON IMBONINI INDUSTRIAL PARK TIFFANY’S GOLF SHAKA’S MHALALI ESTATE HEAD SHOPPING CENTRE SO-HIGH SHAKA’S PRE-PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PARK SCHOOL BROOKLYN SHEFFIELD SHORTENS MANOR ESTATE UMHLALI COUNTRY EDEN VILLAGE CLUB TANGLEWOOD THE LITCHI BLYTHEDALE WESTBROOK ORCHARD COASTAL ESTATE VILLAGE ELALENI KIDZ CURRO BRETTENWOOD WAKENSHAW SCHOOL ZULULAMI MDLOTANE VIRGIN ACTIVE GYM ECO-KIDZ PRE-SCHOOL LIFESTYLE BALLITO DUNKIRK EQUESTRIAN SIMBITHI CENTRE JUNCTION CENTRE COUNTRY MONT CLUB MOUNT SHEFFIELD SIMBITHI RICHMORE CALM ECO ESTATE RETIREMENT VILLAGE BEACH ASHTON GRANTPRINCE’S GOLF COLLEGE NEW SALT BIRDHAVENLOXLEY ESTATE ROCK CITY ESTATE THE WELL SIMBITHI OFFICE PARK IZULU OFFICE PARK HERON ZINKWAZI COMMUNITY CENTRE BEACH NETCARE ALBERLITO SKI BOAT HOSPITAL LAUNCH SALT ROCK CHRISTMAS TINLEY HOTEL BAY BEACH MANOR SHEFFIELD BEACH DOLPHIN COAST PRE-PRIMARY SALT BEACH ROCK GRANNY TIFFANY’S CARAVAN POOLS BALLITO PARK BEACH CARAVAN PARK SALT ROCK PROMENADE BEACH TIDAL POOL THOMPSON’S CLARKE BAY SALMON TIDAL BLYTHEDALE ZINKWAZI BAY WILLARD’S BAY POOL BEACH BALLITO SHAKA’S ROCK SALT ROCK SHEFFIELD TINLEY MANOR. -

Kim Spingorum

Kindly be advised should you be coming with a boat, jet skis or canoe/kayak to contact our local ski boat club manager, contact person Charles Rautenbach, to get the necessary clearances or any additional info re water sport facilities on the lagoon. Cell: 083 375 5399 Brian is the local skipper for all things fishing and for booking a cruise on the barge on the lagoon – for more details contact, 084 446 6813 / 074 479 0987. Have fun! (Ocean echo fishing charters) Or simply just paddle, fish or swim in our lagoon. – Double or single canoes for hire at R40/per hour from the Lagoon lodge – contact: 032 – 485 3344 For additional water escapades in Durban and surrounds including Ballito please have a look at https://adventureescapades.co.za/water-adventures-in-south-africa/ Sugar Rush fun park for the whole family – www.sugarrush.co.za - on the coastal farmland of the North Coast, on the outskirts of Ballito – please have a look at the website for more information. • Putt-putt with paddling pools after the kids have played their holes • Small winery • The Jump Park • Tuwa Beauty Spa • Petting Zoo – Feathers and Furballs • Sugar rats – Kids Mountain biking, safe and fun! • Reptile Park • Restaurant Holla Trails operates from Sugar rush For those who are interested in doing a bike or for the runners!!– Holla trails can be contacted on +27 074 897 8559 (trail master) or 082 899 3114 (desk phone) – Easy to get to situated on the outskirts of Ballito! A fun way to experience the farm life on the North Coast, the trails are for different levels from under 12 to 70 years. -

The Employment Security Program in a Changing Economic Situation

The Employment Secwity Pmgram in a . Changing Economic Situation The Federal Advisory Council of the Bureau of Employment that, during the last 3 years, con- Security at its meeting this past September adopted resolu- gressional appropriations for the op- tions, given in full in the following pages, on the employment erational functions of the United service and on unemployment insurance. The conference, States Employment Service and the which was the Council’s first since the Bureau’s transfer from Veterans Employment Service have the Social Security Administration to the Department of Labor, necessitated drastic curtailment of heard brief statements from the Secretary and the Under Secre- personnel of both services, with a tary of Labor, as well as from Arthur J. Altmeyer, Commissioner consequent drastic reduction in the for Social Security, and Robert C. Goodwin, Director of the counseling, job development, place- Bureau of Employment Security. A summary of Mr. Altmeyer’s ment, and other essential activities statement follows the recommendations. of the United States Employment Service and the Veterans Employment Service. HE Federal Advisory Council of ties of the Employment Service to It is absolutely essential that ade- the Bureau of Employment Se- date in providing leadership in com- quate appropriations be made by Con- T curity met in Washington on munity employment planning. gress for these purposes, if the promise September 14 and 15. 1949. The In addition, it recommends that set forth in the Servicemen’s Read- Council, established under the Wag- State and local “maximum employ- justment Act that “there shall be an ner-Peyser Act, has 35 members, who ment committees” be established to effective job counseling and employ- represent business, labor, veterans’ bring the entire resources of the com- ment placement service for vet- groups, and the general public. -

Alternatives to Money-As-Usual in Ecological Economics: a Study of Local Currencies and 100 Percent Reserve Banking

Doctoral dissertation Alternatives to Money-As-Usual in Ecological Economics: A Study of Local Currencies and 100 Percent Reserve Banking Kristofer Dittmer September 2014 Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals (ICTA) Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) Ph.D. Programme in Environmental Science and Technology Ecological Economics and Environmental Management Supervisor: Dr. Louis Lemkow Professor ICTA and Department of Sociology UAB i ii Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... v Resumen ............................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. x Preface .................................................................................................................................................. xii 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Subject of research ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Ecological economics .................................................................................................................. 4 1.3. Frederick Soddy’s contribution -

BUYING LOCAL: Tools for Forward-Thinking Institutions

A RESOURCE GUIDE Buying Local TOOLS FOR FORWARD-THINKING INSTITUTIONS > Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge a number of people who contributed to this study. The following people were consulted for their opinions and experiences regarding local procurement. Their contribution to this report was invaluable. Larry Berglund Supply chain management professional and consultant Brita Cloghesy-Devereux Partnerships and community investment manager, Vancity Credit Union Maureen Cureton Green business manager, Vancity Credit Union Ben Isitt Victoria city councillor and regional director Elizabeth Lougheed Green Manager of community investment (Impact Business Development) at Vancity Savings Credit Union Jack McLeman Port Alberni city councillor Josie Osborne Mayor, Tofino Michael Pacholok Director, Purchasing and Materials Management division, City of Toronto Lynda Rankin Manager, Sustainable Procurement, Government of Nova Scotia Tim Reeve Sustainable procurement professional and consultant Amy Robinson Founder and executive director, LOCO B.C. Victoria Wakefield Purchasing manager, Student Housing and Hospitality Services at the University of British Columbia Juvarya Warsi Economic strategist, Vancouver Economic Commission Mike Williams General manager, Economic Development & Culture, City of Toronto Rob Wynen Vancouver School Board trustee BUYING LOCAL: Tools for Forward-Thinking Institutions by Robert Duffy and Anthony Pringle Editing: Charley Beresford, Helen Guri December 2013 ©Columbia Institute, LOCO BC, and ISIS Research -

KWADUKUZA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY the KWAZULU-NATAL SCHEME SYSTEM Zoning Companion Document 1

KWADUKUZA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY THE KWAZULU-NATAL SCHEME SYSTEM Zoning Companion Document 1 NOVEMBER 2016 Prepared for: The Municipal Manager KwaDukuza Local Municipality 14 Chief Albert Luthuli Street KwaDukuza 4450 Tel: +27 032 437 5000 E-mail: [email protected] Contents 1.0 DEFINING LAND USE MANAGEMENT? ......................................................................................... 3 2.0 WHY DO WE NEED TO MANAGE LAND? ..................................................................................... 3 3.0 WHAT IS LAND USE PLANNING? ................................................................................................... 4 4.0 WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR LAND USE PLANNING? ................................................................ 4 5.0 THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................... 5 6.0 MANAGING LAND THROUGH A SUITE OF PLANS .................................................................... 6 7.0 WHAT ARE THE ELEMENTS OF THE LAND USE SCHEME? ................................................. 11 7.1 STATEMENTS OF INTENT (SOI) .............................................................................................. 11 7.2 LAND USE DEFINITIONS............................................................................................................. 12 7.3 ZONES 12 7.4 THE SELECTION OF ZONES AND THE PREPARATION OF A SCHEME MAP ................ 13 8.0 DEVELOPMENT PARAMETERS / SCHEME CONTROLS .......................................................