Imputed Righteousness: the Apostle Paul and Isaiah 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Points of Calvinism

• TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Bethlehem College & Seminary 720 13th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55415 612.455.3420 [email protected] | bcsmn.edu Copyright © 2007, 2012, 2017 by Bethlehem College & Seminary All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, modified, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Scripture taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Copyright © 2007 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. • TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Table of Contents Instructor’s Introduction Course Syllabus 1 Introduction from John Piper 3 Lesson 1 Introduction to the Doctrines of Grace 5 Lesson 2 Total Depravity 27 Lesson 3 Irresistible Grace 57 Lesson 4 Limited Atonement 85 Lesson 5 Unconditional Election 115 Lesson 6 Perseverance of the Saints 141 Appendices Appendix A Historical Information 173 Appendix B Testimonies from Church History 175 Appendix C Ten Effects of Believing in the Five Points of Calvinism 183 Instructor’s Introduction It is our hope and prayer that God would be pleased to use this curriculum for his glory. Thus, the intention of this curriculum is to spread a passion for the supremacy of God in all things for the joy of all peoples through Jesus Christ. This curriculum is guided by the vision and values of Bethlehem College & Seminary which are more fully explained at bcsmn.edu. At the Bethlehem College & Semianry website, you will find the God-centered philosophy that undergirds and motivates everything we do. -

Incorporated Righteousness: a Response to Recent Evangelical Discussion Concerning the Imputation of Christ’S Righteousness in Justification

JETS 47/2 (June 2004) 253–75 INCORPORATED RIGHTEOUSNESS: A RESPONSE TO RECENT EVANGELICAL DISCUSSION CONCERNING THE IMPUTATION OF CHRIST’S RIGHTEOUSNESS IN JUSTIFICATION michael f. bird* i. introduction In the last ten years biblical and theological scholarship has witnessed an increasing amount of interest in the doctrine of justification. This resur- gence can be directly attributed to issues emerging from recent Protestant- Catholic dialogue on justification and the exegetical controversies prompted by the New Perspective on Paul. Central to discussion on either front is the topic of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness, specifically, whether or not it is true to the biblical data. As expected, this has given way to some heated discussion with salvos of criticism being launched by both sides of the de- bate. For some authors a denial of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as the sole grounds of justification amounts to a virtual denial of the gospel itself and an attack on the Reformation. Others, by jettisoning belief in im- puted righteousness, perceive themselves as returning to the historical mean- ing of justification and emancipating the Church from its Lutheranism. In view of this it will be the aim of this essay, in dialogue with the main pro- tagonists, to seek a solution that corresponds with the biblical evidence and may hopefully go some way in bringing both sides of the debate together. ii. a short history of imputed righteousness since the reformation It is beneficial to preface contemporary disputes concerning justification by identifying their historical antecedents. Although the Protestant view of justification was not without some indebtedness to Augustine and medieval reactions against semi-Pelagianism, for the most part it represented a theo- logical novum. -

Justification by an Imputed Righteousness

Justification by an Imputed Righteousness JOHN BUNYAN (1628-1688) Justification by an Imputed Righteousness or No Way to Heaven but by Jesus Christ by John Bunyan (1628-1688) Contents Sinners Justified by Imputation of Righteousness of Christ ..................................... 3 I. Men Are Justified before God while Sinners ......................................................... 6 I.A The Mysterious Act of Our Redemption ......................................................... 6 I.B Men Are Justified while Sinners in Themselves ........................................... 11 I.C More Reasons Men Must Be Justified while They Are Sinners .................. 26 II. Men Can Be Justified Only by the Righteousness of Christ ............................. 39 II.A The Righteousness that Justifieth Was Performed by Christ .................... 39 II.B The Righteousness which Justifieth Is Only Inherent in Christ ............... 40 III. The Uses of Justifying Faith ............................................................................... 44 III.A Take Heed of Seeking Justifying Righteousness in Ourselves ................. 44 III.B Have Faith in Christ ..................................................................................... 46 © Copyright 1999 Chapel Library: compilation, annotations. Published in the USA. Permission is ex- pressly granted to reproduce this material by any means, provided 1) you do not charge beyond a nominal sum for cost of duplication; 2) this copyright notice and all the text on this page are included. Chapel -

The Gospel Wars Lesson #10 Justification & Imputation of Righteousness

The Gospel Wars Lesson #10 Justification & Imputation of Righteousness I. Lesson Introduction The imputation of Christ’s righteousness to we saints is part of the broader act of “Judicial or Forensic Justification” before the face of God. God in a judicial act of grace declares those who have been born again to be righteous based on the accomplished righteousness of Jesus, the Messiah, the God man who lived entirely without sin, fully obedient to the Law of God in all ways. This righteousness of Christ is imputed to His saints. “A right understanding of justification is absolutely crucial to the whole Christian faith. Once Martin Luther realized the truth of justification by faith alone, he became a Christian and overflowed with the new-found joy of the gospel. The primary issue in the Protestant Reformation was a dispute with the Roman Catholic Church over justification.” Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology; p. 722. II. Definitions Forensic: “A term that means ‘having to do with legal proceedings.’ This term is used to describe justification as being a legal declaration by God that in itself does not change our internal nature or character.” . Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology, p. 1242 Imputation: “To think of as belonging to someone, and therefore to cause it to belong to that person. God ‘thinks of’ Adam’s sin as belonging to us, and it therefore belongs to us, and in justification He thinks of Christ’s righteousness as belonging to us and so relates to us on this basis.” Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology, p. 1245 There are 3 distinct, but related concepts of imputation mentioned in Scripture. -

Alien Righteousness? a Re-Examination of the Idea That Believers Are Clothed in the Righteousness of Christ

¯Title Page Alien Righteousness? A Re-examination Of The Idea That Believers Are Clothed In The Righteousness Of Christ Roderick Graciano And it was given to her to clothe herself in fine linen, bright and clean; for the fine linen is the righteous acts of the saints. Revelation 19.8 i Copyright Notices King James Version of the English Bible, © 1997 by the Online Bible Foundation and Woodside Fellowship of Ontario, Canada. The New American Standard Bible, © 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. The Holy Bible: New International Version, © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. The New King James Version, © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. All Scripture citations are from The New American Standard Bible, © 1995 by The Lockman Foundation, (abbreviated NAU in the narrative) unless otherwise noted. Other versions are normally identified in superscript abbreviation at the verse citation. Because The New American Standard Bible uses italics to identify words and phrases that are not in the original language text, emphasis is occasionally added in this work by using bold type. Permission Permission is hereby given to quote, copy and distribute all or a portion of Alien Righteousness? so long as no portion of it is sold nor used in a work that is for sale, and so long as the author is credited along with www.timothyministries.info as the source, and 2011 is indicated as the copyright date. Any use of all or part of Alien Righteousness? in a work or collection involving, or sold for, a monetary charge requires the express permission of the author who can be contacted at [email protected] . -

Irresistible Grace

TULIP: A FREE GRACE PERSPECTIVE PART 4: IRRESISTIBLE GRACE ANTHONY B. BADGER Associate Professor of Bible and Theology Grace Evangelical School of Theology Lancaster, Pennsylvania I. INTRODUCTION Can God’s gift of eternal life be resisted? Does God’s sovereignty require that He force selected people (the elect) to receive His gift of salvation and to enter into a holy union with Him? Is it an affront to God to suggest that the Holy Spirit can be successfully resisted? Calvinist or Reformed Theology, will usually reason that since God is all-powerfully sovereign and since man is completely and totally unable to believe in Christ, it is necessary that God enforce His grace upon those whom He has elected for eternal life. We will now consider the Calvinistic view and the Arminian response to this doctrine. II. THE REFORMED VIEW OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE Hughes concisely says, Irresistible grace is grace which cannot be rejected. The con- ception of the irresistibility of special grace is closely bound up with...the efficacious nature of that grace. As the work of God always achieves the effect toward which it is directed, so also it cannot be rejected or thrust aside.1 Steele, Thomas, and Quinn present a slightly longer explanation—the doctrine of “The Efficacious Call of the Spirit or Irresistible Grace” say- ing, In addition to the outward general call to salvation which is made to everyone who hears the gospel, the Holy Spirit ex- tends to the elect a special inward call that inevitably brings them to salvation. The external call (which is made to all 1 P. -

Dual Imputation: the Righteousness of Jesus Christ Credited to the Believer Exegetically Defended

DUAL IMPUTATION: THE RIGHTEOUSNESS OF JESUS CHRIST CREDITED TO THE BELIEVER EXEGETICALLY DEFENDED Geoffrey Randall Kirkland Box #147 TH824 – Seminar in Soteriology April 2, 2008 CONTENTS Introduction..................................................................................................................... 3 Getting Facts Straight ................................................................................................. 3 Old Testament Terminology....................................................................................... 4 New Testament Terminology ..................................................................................... 5 Justification Defined ................................................................................................... 6 Imputation Defined ..................................................................................................... 7 The Problem.................................................................................................................... 8 Exegetical Proof of Imputation..................................................................................... 10 Romans 4:3 ............................................................................................................... 10 Romans 5:19 ............................................................................................................. 13 Philippians 3:9 .......................................................................................................... 15 1 Corinthians 1:30.................................................................................................... -

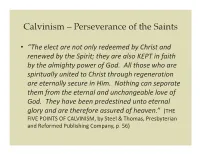

Calvinism – Perseverance of the Saints

Calvinism – Perseverance of the Saints • “The elect are not only redeemed by Christ and renewed by the Spirit; they are also KEPT in faith by the almighty power of God. All those who are spiritually united to Christ through regeneration are eternally secure in Him. Nothing can separate them from the eternal and unchangeable love of God. They have been predestined unto eternal glory and are therefore assured of heaven.” (THE FIVE POINTS OF CALVINISM, by Steel & Thomas, Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, p. 56) Calvinism – Perseverance of the Saints • “The doctrine of the perseverance of the saints does not maintain that all who PROFESS the Christian faith are certain of heaven. It is SAINTS – those who are set apart by the Spirit – who PERSEVERE to the end. It is BELIEVERS – those who are given true, living faith in Christ – who are SECURE and safe in Him. Many who profess to believe fall away, but they do not fall from grace for they were never in grace. True believers do fall into temptations, and they do commit grievous sins, but these sins do not cause them to lose their salvation or separate them from Christ.” (THE FIVE POINTS OF CALVINISM, by Steel & Thomas, Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, p. 56) Calvinism – Perseverance of the Saints • “The Westminster Confession of Faith gives the following statement of this doctrine: ‘They whom God hath accepted in His Beloved, effectually called and sanctified by His Spirit, can neither totally nor finally fall away from the state of grace, but shall certainly persevere therein to the end, and be eternally saved.’” (THE FIVE POINTS OF CALVINISM, by Steel & Thomas, Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, p. -

Imputed Righteousness by Kyle Pope

Imputed Righteousness By Kyle Pope Introduction. Imputation is a largely Protestant doctrine that teaches that the sins or good deeds of one may be accounted or credited to another.1 A. Historical Development of the Doctrine of Imputation. 1. Although some aspects of its various forms date to the teachings of Anselm, the archbishop of Canterbury (c. 1033-1109), it assumed its most prominent form during the Protestant reformation. 2. Imputation vs. Infusion. Unlike the Roman Catholic concept that Christ’s righteousness is gradually infused into a believer as he or she partakes of (what the Catholics call) sacraments, the Reformers argued that just as they believed Adam’s sin was imputed to all men, Christ’s righteousness is imputed (or credited) to the elect. 3. A Reformed Doctrine. While this is generally considered a Calvinistic doctrine, Luther did much to shape its prominent form among Protestants.2 a. In fact, there is some evidence that Calvin himself did not take it to the extremes that his Calvinistic followers would come to adopt. So in some cases Calvin was not a Calvinist.3 B. Protestant Debates Regarding Imputation. 1. Since the Reformation imputation has remained a fundamental Protestant doctrine, but Protestants have differed over a number of things regarding its precise tenets. a. This is seen in debates over whether Christ’s active or only passive righteousness—that is His righteous acts coram mundo (“before the world”) or His righteous acts coram Deo (“before God”)—are both credited to the saved.4 1 English Bibles use various forms of the verb “impute” to translate Hebrew and Greek words that address what God accounts or reckons to human beings—KJV (16); ASV (6); NASB (3); NKJV (12); ESV (2). -

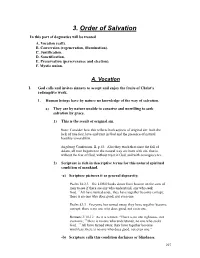

3. Order of Salvation in This Part of Dogmatics Will Be Treated A

3. Order of Salvation In this part of dogmatics will be treated A. Vocation (call). B. Conversion (regeneration, illumination). C. Justification. D. Sanctification. E. Preservation (perseverance and election). F. Mystic union. A. Vocation I. God calls and invites sinners to accept and enjoy the fruits of Christ's redemptive work. 1. Human beings have by nature no knowledge of the way of salvation. a) They are by nature unable to conceive and unwilling to seek salvation by grace. 1) This is the result of original sin. Note: Consider how this reflects both aspects of original sin: both the lack of true fear, love and trust in God and the presence of natural hostility toward him. Augsburg Confession, II, p 43: Also they teach that since the fall of Adam, all men begotten in the natural way are born with sin, that is, without the fear of God, without trust in God, and with concupiscence. 2) Scripture is rich in descriptive terms for this natural spiritual condition of mankind. -a) Scripture pictures it as general depravity. Psalm 14:2,3 The LORD looks down from heaven on the sons of men to see if there are any who understand, any who seek God. 2 All have turned aside, they have together become corrupt; there is no one who does good, not even one. Psalm 53:3 Everyone has turned away, they have together become corrupt; there is no one who does good, not even one. Romans 3:10-12 As it is written: “There is no one righteous, not even one; 11 there is no one who understands, no one who seeks God. -

Wesley on Imputation: a Truly Reckoned Reality Or Antinomian Polemical Wreckage?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary WESLEY ON IMPUTATION: A TRULY RECKONED REALITY OR ANTINOMIAN POLEMICAL WRECKAGE? WOODROW W. WHIDDEN THE REfoRMED REACTION Protestants have long been uncomfortable with Wesley's understanding of justifi- cation by faith. The usual suspicions surface with whispers of "pelagianism," "syner- gism," "Romanist moralism," and "legalism." In his own time he was under close scrutiny from the Calvinistic wing of the Evangelical Revival. Such scrutiny erupted into a storm of protest with the publication of the infamous "1770 Minutes." These "Minutes" have received most of the attention of Wesleyan scholars as they have sought to assess the genuineness of Wesley's Protestant credentials.' A SEEMINGLY ANOMALOUS STATEMENT What is somewhat surprising is the almost total lack of attention given to Wesley's negative, delimiting comments on "faith alone" in the "first fully positive exposition of his 'new' soteriology"'-his sermon entitled "justification by Faith." 3 After plainly stating that justification "is not being made actually just and righteous,"' Wesley gives this troubling anomalous qualifier: Least of all does justification imply that God is deceived in those whom he jus- tifies; that he thinks them to be what in fact they are not, that he accounts them to be otherwise than they are. It does by no means imply that God judges concerning us contraty to the real nature of things, that he esteems us better than we really are, or believes us righteous when we are unrighteous. Surely no. The judgment of the all-wise God is always according to truth. -

Journal of Theology Spring 2017 Volume 57 Number 1

Spring 2017 Volume 57 Number 1 _______________________ CONTENTS In the Footsteps of the Reformers: Johann Heermann ………..………………………… 3 David J. Reim An Exegetical Notebook: Romans 10:4 ………………………………………………………….. 8 Mark S. Tiefel “Game Changers” of Jesus in John’s Gospel Account …………………………………… 11 Paul M. Tiefel Objective and Subjective Justification as a Lutheran Hermeneutic ………………. 20 Timothy T. Daub Imputation of Righteousness ……….…………………………………………………………….. 31 John V. Klatt Book Reviews David T. Lau Lives and Writings of the Great Fathers of the Lutheran Church …………40 The Qur'an in Context – A Christian Exploration …………………………………42 1 / 44 Editor: Wayne C. Eichstadt / 11315 E. Broadway Avenue / Spokane Valley, WA 99206 / [email protected] / (509) 926-3317 Assistant Editor: Norman P. Greve Business Manager: Benno Sydow / 2750 Oxford St. North/ Roseville, MN 55113 / [email protected] Staff Contributors: D. Frank Gantt, David T. Lau, Nathanael N. Mayhew, Bruce J. Naumann, Paul G. Naumann, John K. Pfeiffer, David J. Reim, Michael J. Roehl, Steven P. Sippert, David P. Schaller, Paul M. Tiefel Jr., Mark S. Tiefel Correspondence regarding subscriptions, renewals, changes of address, failed delivery, and copies of back issues should be directed to the Business Manager. Any other correspondence regarding the Journal of Theology, including the website, should be directed to the editor. © 2017 by the Church of the Lutheran Confession. Please contact the editor for permission to reproduce more than brief excerpts or other “fair use.” All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright ©1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (AAT) are taken from The Holy Bible, An American Translation, 1976, William F.