A Comprehensive Approach to Playing the Drumset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Owner S Manual

HD-4 Owner s Manual Virgin Musical Instruments Precaution Thank you for purchasing this electronic instrument.For perfect operation and security, please read the manual carefully and keep it for future reference. Safety Precautions CAUTION RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK DO NOT OPEN The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage”within the product s enclosure that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the presence of important operating and maintenance(servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the product. Important Safety Instructions 1) Read these instructions. apparatus. When a cart is used, use caution when 2) Keep these instructions. moving the cart/apparatus combination to avoid 3) Heed all warnings. injury from tip-over(Figure 1). 4) Follow all instructions. (Figure 1) 13) Unplug this apparatus during lightning storms 5) Do not use this apparatus near water. or when unused for a long periods fo time. 6) Clean only with dry cloth. 14) Refer all servicing to qualified service personnel. 7) Do not block any ventilation openings, install in Servicing is required when the apparatus has been accordance with the manufacturer s instructions. damaged in any way, such as power-supply cord or 8) Do not install near the heat sources such as plug is damaged, liquid has been spilled or objects radiators, heat registers, stoves, or other apparatus have fallen into the apparatus, the apparatus has (including amplifiers) that produce heat. -

Owner's Manual 5057870-B

OWNER’S MANUAL WARRANTY We at DigiTech® are very proud of our products and back-up each one we sell with the following warranty: 1. Please register online at digitech.com within ten days of purchase to validate this warranty. This warranty is valid only in the United States. 2. DigiTech warrants this product, when purchased new from an authorized U.S. DigiTech dealer and used solely within the U.S., to be free from defects in materials and workmanship under normal use and service. This warranty is valid to the original purchaser only and is non-transferable. 3. DigiTech liability under this warranty is limited to repairing or replacing defective materials that show evidence of defect, provided the product is returned to DigiTech WITH RETURN AUTHORIZATION, where all parts and labor will be covered up to a period of one year. A Return Authorization number may be obtained by contacting DigiTech. The company shall not be liable for any consequential damage as a result of the product’s use in any circuit or assembly. 4. Proof-of-purchase is considered to be the responsibility of the consumer. A copy of the original purchase receipt must be provided for any warranty service. 5. DigiTech reserves the right to make changes in design, or make additions to, or improvements upon this product without incurring any obligation to install the same on products previously manufactured. 6. The consumer forfeits the benefits of this warranty if the product’s main assembly is opened and tampered with by anyone other than a certified DigiTech technician or, if the product is used with AC voltages outside of the range suggested by the manufacturer. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

HD-17 Mako E-Drum Set

HD-17 Mako e-drum set user manual Musikhaus Thomann Thomann GmbH Hans-Thomann-Straße 1 96138 Burgebrach Germany Telephone: +49 (0) 9546 9223-0 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.thomann.de 08.01.2019, ID: 429328 Table of contents Table of contents 1 General information.............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Further information........................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Notational conventions................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Symbols and signal words........................................................................................... 5 2 Safety instructions................................................................................................................. 6 3 Features....................................................................................................................................... 8 4 Scope of delivery..................................................................................................................... 9 5 Assembly.................................................................................................................................. 10 6 Drum seat assembly (option)......................................................................................... 14 7 Installation............................................................................................................................. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

KT4-Manual.Pdf

aaw_KT4_manual_G05_151029.aiw_KT4_manual_G05_151029.ai 1 22015/10/29015/10/29 113:33:083:33:08 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K aaw_KT4_manual_G05_151029.aiw_KT4_manual_G05_151029.ai 2 22015/10/29015/10/29 113:33:543:33:54 INFORMATION FOR YOUR SAFETY! PRECAUTIONS This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. Operation is subject to the following two conditions: PLEASE READ CAREFULLY BEFORE PROCEEDING (1) this device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference received, including interference that may cause undesired Please keep this manual in a safe place for future reference. operation. Power Supply Please connect the designated AC adaptor to an AC outlet of the correct voltage. FCC COMPLIANCE NOTICE Do not connect it to an AC outlet of voltage other than that This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the for which your instrument is intended. limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable Unplug the AC power adaptor when not using the protection against harmful interference in a residential instrument, or during electrical storms. installation. This equipment generates, uses and can radiate radio frequency energy and if not used in accordance with the Connections instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio Before connecting the instrument to other devices, turn off communications and there is no guarantee that interference the power to all units. This will help prevent malfunction and will not occur in a particular installation. If this equipment does / or damage to other devices. -

Owner's Manual 5064509-A

OWNER’S MANUAL WARRANTY We at DigiTech® are very proud of our products and back-up each one we sell with the following warranty: 1. Please register online at digitech.com within ten days of purchase to validate this warranty. This warranty is valid only in the United States. 2. DigiTech warrants this product, when purchased new from an authorized U.S. DigiTech dealer and used solely within the U.S., to be free from defects in materials and workmanship under normal use and service. This warranty is valid to the original purchaser only and is non-transferable. 3. DigiTech liability under this warranty is limited to repairing or replacing defective materials that show evidence of defect, provided the product is returned to DigiTech WITH RETURN AUTHORIZATION, where all parts and labor will be covered up to a period of one year (this warranty is extended to a period of six years when the product has been properly registered through our website). A Return Authorization number may be obtained by contacting DigiTech. The company shall not be liable for any consequential damage as a result of the product’s use in any circuit or assembly. 4. Proof-of-purchase is considered to be the responsibility of the consumer. A copy of the original purchase receipt must be provided for any warranty service. 5. DigiTech reserves the right to make changes in design, or make additions to, or improvements upon this product without incurring any obligation to install the same on products previously manufactured. 6. The consumer forfeits the benefits of this warranty if the product’s main assembly is opened and tampered with by anyone other than a certified DigiTech technician or, if the product is used with AC voltages outside of the range suggested by the manufacturer. -

SYMPHONY GRAND Digital Piano

SYMPHONY GRAND digital piano owner's manual IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS • Do not use near water. • Clean only with a soft, dry cloth. • Do not block any ventilation openings. • Do not place near any heat sources such as radiators, heat registers, stoves, or any other apparatus (including amplifiers) that produces heat. • Do not remove the polarized or grounding-type plug. • Protect the power cord from being walked on or pinched. • Only use the included attachments/accessories. • Unplug this apparatus during lightning storms or when unused for a long period of time. • Refer all servicing to qualified service personnel. Servicing is equiredr when the apparatus has been damaged in any way, such as power-supply cord or plug is damaged, liquid has been spilled or objects have fallen into the apparatus, the apparatus has been exposed to rain or moisture, does not operate normally, or has been dropped. FCC STATEMENTS 1. Caution: Changes or modifications to this unit not expressly approved by the party responsible for compliance could void the user’s authority to operate the equipment. 2. NOTE: This equipment has been tested and found to comply with a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. However, there is no guar- antee that interference will not occur in a particular installation. If this equipment does cause harmful interference to radio or television reception, which can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to try to correct the interference by one or more of the following measures: • Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. -

About This Lesson

THIS LESSON IS EXCERPTED FROM ASK FOR IT AT YOUR FAVORITE MUSIC STORE OR BUY IT ONLINE AT: WWW.MWPUBLICATIONS.COM ABOUT THIS LESSON: Lesson 28 is the fourth of five lessons on jazz fundamentals. Lesson 25 deals with basic swing grooves and fills, 26 is all about comping under the ride, 27 gets into setting up ensemble figures, and Lesson 28 deals with more complicated ensemble figures. When writing the book, it struck me that many others deal with setting up an initial ensemble entrance, but none deal with filling around figures AFTER the entrance. Also important are learning ensemble articulations so that you can orchestrate note lengths with the various sounds on the drumset. Included are two sound files to practice some sample figures (#4 – a two measure phrase and #9 – a four measure phrase). In these sound files, you’ll play time with a bass player, then set up and fill around the figures played by the pianist. The full play along track is a typical small group chart. As with all jazz, there is no set “drum part” – what you play is completely up to you. Feel free to copy some of the licks that Donny Gruendler plays on the track with drums, or make up your own! Good luck and have fun! Mark Wessels 28 28 More Complicated Ensemble Figures A-L Providing a setup for an ensemble entrance is just one of the drummer’s roles in a jazz setting. Usually a chart will also include important ensemble figures as well. It’s the drummer’s job to “catch” these figures – by either comping under the ride (with the snare and/or bass drum for example), or by playing fills to set up and ‘punch’ syncopated figures. -

KROSS Voice Name List

Voice Name List 1 Table of Contents Programs . .3 27(INT): Percussion Kit. 49 Category: PIANO . .3 28(INT): Orchestra&Ethno Kit . 50 Category: E.PIANO . .4 29(INT): BD&SD Catalog 1. 52 Category: ORGAN . .5 30(INT): BD&SD Catalog 2. 53 Category: BELL. .6 31(INT): Cymbal Catalog . 54 Category: STRINGS . .7 32(INT): Rock Kit 1 Mono. 55 Category: BRASS . .8 33(INT): Jazz Kit Mono . 56 Category: SYNTH LEAD . .9 34(INT): Wild Kit . 57 Category: SYNTH PAD . 10 35(INT): Breakin' Kit. 58 Category: GUITAR . 11 36(INT): R'n'B Kit. 59 Category: BASS . 12 37(INT): Trapper Kit. 60 Category: DRUM/SFX. 13 38(INT): Bigroom Kit . 61 39(INT): Tropical Kit . 62 Combinations. 15 40(INT): JazzyHop Kit . 63 Category: PIANO . 15 41(INT): Japanese Catalog . 64 Category: E.PIANO . 15 Category: ORGAN . 15 GM Drum Kits . 65 Category: BELL. 16 58(GM): STANDARD . 65 Category: STRINGS . 16 59(GM): ROOM . 66 Category: BRASS . 16 60(GM): POWER . 67 Category: SYNTH LEAD . 17 61(GM): ELECTRONIC . 68 Category: SYNTH PAD . 17 62(GM): ANALOG. 69 Category: GUITAR . 18 63(GM): JAZZ . 70 Category: BASS . 18 64(GM): BRUSH. 71 Category: DRUM/SFX. 19 65(GM): ORCHESTRA . 72 66(GM): SFX. 73 Favorites . 20 FAVORITES- A . 20 Preset Arpeggio Patterns/User Arpeggio Patterns 74 FAVORITES- B . 20 FAVORITES- C . 20 Drum Track Patterns/Pattern Presets. 79 FAVORITES- D. 20 Template songs . 82 Drum Kits. 21 P00: Pop . 82 P01: Rock . 82 00(INT): Basic Kit 1. 21 P02: Jazz . 82 01(INT): Basic Kit 2. -

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques JULY 2018 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard) *TC 1-19.30 (TC 12-43) Training Circular Headquarters No. 1-19.30 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 July 2018 Percussion Techniques Contents Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PERCUSSION PLAYING ................................................. 1-1 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Definitions .................................................................................................................. 1-1 Total Percussionist .................................................................................................... 1-1 General Rules for Percussion Performance .............................................................. 1-2 Chapter 2 SNARE DRUM .......................................................................................................... 2-1 Snare Drum: Physical Composition and Construction ............................................. -

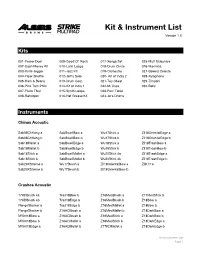

Strike Multipad Kit & Instrument List

Kit & Instrument List Version 1.0 Kits 001-Power Duel 009-Good Ol' Rock 017-Xonga Set 025-Mult Sidesnare 002-Cash Money Kit 010-Latin Loops 018-Drum Circle 026-Marimba 003-Knife Jogger 011-Jazz Kit 019-Orchestra 027-Bowed Celeste 004-Piper Shuffle 012-Jeff's Solo 020- Kit of India 2 028-Xylophone 005-Ham & Beans 013-Drum Corp 021-Toy Chest 029-Timpani 006-Pink Tom Phils 014-Kit of India 1 022-Mi Casa 030-Bells 007-Pluck This! 015-Synth Loops 023-Perc Table 008-Randojon 016-Hat Grease Kit 024-Jo's Drums Instruments Chinas Acoustic Sab08ChKang a SabBwellBow a Wu17Stick a Zil18OrientalEdge a Sab08ChKang b SabBwellBow b Wu17Stick b Zil18OrientalEdge b Sab18Mallet a SabBwellEdge a Wu18Stick a Zil18TrashBow a Sab18Mallet b SabBwellEdge b Wu18Stick b Zil18TrashBow b Sab18Stick a SabBwellMallet a Wu20Stick 4a Zil18TrashEdge a Sab18Stick b SabBwellMallet b Wu20Stick 4b Zil18TrashEdge b Sab20XStreme a Wu17Brush a Zil18OrientalBow a ZilK17 a Sab20XStreme b Wu17Brush b Zil18OrientalBow b Crashes Acoustic 17KDBrush 4a Trad18Bow b Z16MedBrush a Z17MedStick b 17KDBrush 4b Trad18Edge a Z16MedBrush b Z18Bow a FlangeStacker a Trad18Edge b Z16MedMallet a Z18Bow b FlangeStacker b Z16ACBrush a Z16MedMallet b Z18DarkBow a MVint18Bow a Z16ACBrush b Z16MedStick a Z18DarkBow b MVint18Bow b Z16ACMallet a Z16MedStick b Z18DarkEdge a MVint18Edge a Z16ACMallet b Z17KDMallet a Z18DarkEdge b Kit & Instrument List Page 1 Crashes Acoustic (continued) PSSab Stacker a Z16ACStick b Z17KDStick a Z18Edge b PSSab Stacker b Z16DarkBrush a Z17KDStick b Z18MedBrush a Smashed17in