Western Australian Naturalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Port Hedland AREA PLANNING STUDY

Port Hedland AREA PLANNING STUDY Published by the Western Australian Planning Commission Final September 2003 Disclaimer This document has been published by the Western Australian Planning Commission. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith and on the basis that the Government, its employees and agents are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which may occur as a result of action taken or not taken (as the case may be) in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. Professional advice should be obtained before applying the information contained in this document to particular circumstances. © State of Western Australia Published by the Western Australian Planning Commission Albert Facey House 469 Wellington Street Perth, Western Australia 6000 Published September 2003 ISBN 0 7309 9330 2 Internet: http://www.wapc.wa.gov.au e-mail: [email protected] Phone: (08) 9264 7777 Fax: (08) 9264 7566 TTY: (08) 9264 7535 Infoline: 1800 626 477 Copies of this document are available in alternative formats on application to the Disability Services Co-ordinator. Western Australian Planning Commission owns all photography in this document unless otherwise stated. Port Hedland AREA PLANNING STUDY Foreword Port Hedland is one of the Pilbara’s most historic and colourful towns. The townsite as we know it was established by European settlers in 1896 as a service centre for the pastoral, goldmining and pearling industries, although the area has been home to Aboriginal people for many thousands of years. In the 1960s Port Hedland experienced a major growth period, as a direct result of the emerging iron ore industry. -

Driving in Wa • a Guide to Rest Areas

DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Driving in Western Australia A guide to safe stopping places DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Contents Acknowledgement of Country 1 Securing your load 12 About Us 2 Give Animals a Brake 13 Travelling with pets? 13 Travel Map 2 Driving on remote and unsealed roads 14 Roadside Stopping Places 2 Unsealed Roads 14 Parking bays and rest areas 3 Litter 15 Sharing rest areas 4 Blackwater disposal 5 Useful contacts 16 Changing Places 5 Our Regions 17 Planning a Road Trip? 6 Perth Metropolitan Area 18 Basic road rules 6 Kimberley 20 Multi-lingual Signs 6 Safe overtaking 6 Pilbara 22 Oversize and Overmass Vehicles 7 Mid-West Gascoyne 24 Cyclones, fires and floods - know your risk 8 Wheatbelt 26 Fatigue 10 Goldfields Esperance 28 Manage Fatigue 10 Acknowledgement of Country The Government of Western Australia Rest Areas, Roadhouses and South West 30 Driver Reviver 11 acknowledges the traditional custodians throughout Western Australia Great Southern 32 What to do if you breakdown 11 and their continuing connection to the land, waters and community. Route Maps 34 Towing and securing your load 12 We pay our respects to all members of the Aboriginal communities and Planning to tow a caravan, camper trailer their cultures; and to Elders both past and present. or similar? 12 Disclaimer: The maps contained within this booklet provide approximate times and distances for journeys however, their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Main Roads reserves the right to update this information at any time without notice. To the extent permitted by law, Main Roads, its employees, agents and contributors are not liable to any person or entity for any loss or damage arising from the use of this information, or in connection with, the accuracy, reliability, currency or completeness of this material. -

Research Matters Newsletter of the Australian Flora Foundation

A charity fostering scientific research into the biology and cultivation of the Australian flora Research Matters Newsletter of the Australian Flora Foundation No. 31, January 2020 Inside 2. President’s Report 2019 3. AFF Grants Awarded 5. Young Scientist Awards 8. From Red Boxes to the World: The Digitisation Project of the National Herbarium of New South Wales – Shelley James and Andre Badiou 13. Hibbertia (Dilleniaceae) aka Guinea Flowers – Betsy Jackes 18. The Joy of Plants – Rosanne Quinnell 23. What Research Were We Funding 30 Years Ago? 27. Financial Report 28. About the Australian Flora Foundation President’s Report 2019 Delivered by Assoc. Prof. Charles Morris at the AGM, November 2019 A continuing development this year has been donations from Industry Partners who wish to support the work of the Foundation. Bell Art Australia started this trend with a donation in 2018, which they have continued in 2019. Source Separation is now the second Industry Partner sponsoring the Foundation, with a generous donation of $5,000. Other generous donors have been the Australian Plants Society (APS): APS Newcastle ($3,000), APS NSW ($3,000), APS Sutherland ($500) and SGAP Mackay ($467). And, of course, there are the amounts from our private donors. In August, the Council was saddened to hear of the death of Dr Malcolm Reed, President of the Foundation from 1991 to 1998. The Foundation owes a debt of gratitude to Malcolm; the current healthy financial position of the Foundation has its roots in a series of large donations and bequests that came to the Foundation during his tenure. -

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia By: D.A. Cumming, D. Garratt, M. McCarthy, A. WoICe With <.:unlribuliuns from Albany Seniur High Schoul. M. Anderson. R. Howard. C.A. Miller and P. Worsley Octobel' 1995 @WAUUSEUM Report: Department of Matitime Archaeology, Westem Australian Maritime Museum. No, 98. Cover pholograph: A view of Halllelin Bay in iL~ heyday as a limber porl. (W A Marilime Museum) This study is dedicated to the memory of Denis Arthur Cuml11ing 1923-1995 This project was funded under the National Estate Program, a Commonwealth-financed grants scheme administered by the Australian HeriL:'lge Commission (Federal Government) and the Heritage Council of Western Australia. (State Govenlluent). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Heritage Council of Western Australia Mr lan Baxter (Director) Mr Geny MacGill Ms Jenni Williams Ms Sharon McKerrow Dr Lenore Layman The Institution of Engineers, Australia Mr Max Anderson Mr Richard Hartley Mr Bmce James Mr Tony Moulds Mrs Dorothy Austen-Smith The State Archive of Westem Australia Mr David Whitford The Esperance Bay HistOIical Society Mrs Olive Tamlin Mr Merv Andre Mr Peter Anderson of Esperance Mr Peter Hudson of Esperance The Augusta HistOIical Society Mr Steve Mm'shall of Augusta The Busselton HistOlical Societv Mrs Elizabeth Nelson Mr Alfred Reynolds of Dunsborough Mr Philip Overton of Busselton Mr Rupert Genitsen The Bunbury Timber Jetty Preservation Society inc. Mrs B. Manea The Bunbury HistOlical Society The Rockingham Historical Society The Geraldton Historical Society Mrs J Trautman Mrs D Benzie Mrs Glenis Thomas Mr Peter W orsley of Gerald ton The Onslow Goods Shed Museum Mr lan Blair Mr Les Butcher Ms Gaye Nay ton The Roebourne Historical Society. -

A New Record of Lortiella Froggatti Iredale, 1934 (Bivalvia: Unionoida

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 28 001–006 (2013) SHORT COMMUNICATION A new record of Lortiella froggatti Iredale, 1934 (Bivalvia: Unionoida: Hyriidae) from the Pilbara region, Western Australia, with notes on anatomy and geographic range M.W. Klunzinger1, H.A. Jones2, J. Keleher1 and D.L. Morgan1 1 Freshwater Fish Group and Fish Health Unit, Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150, Australia. Email: [email protected] 2 Department of Anatomy and Histology, Building F13, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. KEYWORDS: Freshwater mussels, biogeography, species conservation, Australia INTRODUCTION METHODS Accurate delimitation of a species’ geographic range is important for conservation planning and biogeography. SAMPLING METHODS Geographic range limits provide insights into the We compiled 75 distributional records (66 museum ecological and historical factors that infl uence species records and nine fi eld records) of Lortiella species. distributions (Gaston 1991; Brown et al. 1996), whereas Museum records were sourced from Ponder and Bayer the extent of occurrence of a taxon is a key component (2004) and the Online Zoo log i cal Col lec tions of Aus- of IUCN criteria used for assessing the conservation tralian Muse ums (OZCAM 2012). Field records were status of species (IUCN 2001). from sites surveyed for 10–20 minutes by visual and Freshwater mussels (Unionoida) are an ancient group tactile searches in north-western Australia during of palaeoheterodont bivalves that inhabit lotic and lentic 2009–2011. Mussels were preserved in 100% ethanol freshwater environments on every continent except for future molecular study. Water quality data were Antarctica (Graf and Cummings 2006). -

Port Hedland Regional Water Supply

DE GREY RIVER WATER RESERVE WATER SOURCE PROTECTION PLAN Port Hedland Regional Water Supply WATER RESOURCE PROTECTION SERIES WATER AND RIVERS COMMISSION REPORT WRP 24 2000 WATER AND RIVERS COMMISSION HYATT CENTRE 3 PLAIN STREET EAST PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 6004 TELEPHONE (08) 9278 0300 FACSIMILE (08) 9278 0301 WEBSITE: http://www.wrc.wa.gov.au We welcome your feedback A publication feedback form can be found at the back of this publication, or online at http://www.wrc.wa.gov.au/public/feedback/ (Cover Photograph: The De Grey River) _______________________________________________________________________________________________ DE GREY RIVER WATER RESERVE WATER SOURCE PROTECTION PLAN Port Hedland Regional Water Supply Water and Rivers Commission Policy and Planning Division WATER AND RIVERS COMMISSION WATER RESOURCE PROTECTION SERIES REPORT NO. WRP 24 2000 i _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgments Contribution Personnel Title Organisation Supervision Ross Sheridan Program Manager, Protection Planning Water and Rivers Commission Hydrogeology / Hydrology Angus Davidson Supervising Hydrogeologist, Groundwater Water and Rivers Commission Resources Appraisal Report Preparation John Bush Consultant Environmental Scientist Auswest Consultant Ecology Services Dot Colman Water Resources Officer Water and Rivers Commission Rueben Taylor Water Resources Planner Water and Rivers Commission Rachael Miller Environmental Officer Water and Rivers Commission Drafting Nigel Atkinson Contractor McErry Digital Mapping For more information contact: Program Manager, Protection Planning Water Quality Protection Branch Water and Rivers Commission 3 Plain Street EAST PERTH WA 6004 Telephone: (08) 9278 0300 Facsimile: (08) 9278 0585 Reference Details The recommended reference for this publication is: Water and Rivers Commission 1999, De Grey River Water Reserve Water Source Protection Plan, Port Hedland Regional Water Supply, Water and Rivers Commission, Water Resource Protection Series No WRP 24. -

Dormancy Mechanisms of Persoonia Sericea and P. Virgata

Dormancy mechanisms of Persoonia sericea and P. virgata Fruit processing, seed viability and dormancy mechanisms of Persoonia sericea A. Cunn. ex R. Br. and P. virgata R.Br. (Proteaceae) Lynda M. Bauer, Margaret E. Johnston and Richard R. Williams School of Agronomy and Horticulture, The University of Queensland Gatton, Queensland, Australia 4343. Corresponding author Dr Margaret Johnston [email protected] Key words: Australian plant, woody endocarp, digestion, physical dormancy, aseptic culture 1 Summary The morphology of the fruit and difficulties with fruit processing impose major limitations to germination of Persoonia sericea and P. virgata. The mesocarp must be removed without harming the embryo. Fermentation of fruit or manual removal of the mesocarp was effective but digestion in 32% hydrochloric acid (HCl) completely inhibited germination. The endocarp is extremely hard and therefore very difficult and time consuming to remove without damaging the seeds. The most efficient method was cracking the endocarp with pliers, followed by manual removal of seeds. Germination was completely inhibited unless at least half of the endocarp was removed. Microbial contamination of the fruit and seeds was controlled by disinfestation and germination of the seed under aseptic conditions. The results suggest that dormancy in these species is primarily due to physical restriction of the embryo by the hard endocarp. Introduction Persoonia virgata R. Br. is an Australian native shrub with attractive, yellow, bell- shaped flowers. The stems, whether flowering or vegetative, are used as ‘fillers’ in floral bouquets. Even though markets exist for the foliage of P. virgata, it has not been introduced into commercial cultivation due to extreme propagation difficulties. -

Groundwater Resource Assessment and Conceptualization in the Pilbara Region, Western Australia

Earth Systems and Environment https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-018-0051-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Groundwater Resource Assessment and Conceptualization in the Pilbara Region, Western Australia Rodrigo Rojas1 · Philip Commander2 · Don McFarlane3,4 · Riasat Ali5 · Warrick Dawes3 · Olga Barron3 · Geof Hodgson3 · Steve Charles3 Received: 25 January 2018 / Accepted: 8 May 2018 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract The Pilbara region is one of the most important mining hubs in Australia. It is also a region characterised by an extreme climate, featuring environmental assets of national signifcance, and considered a valued land by indigenous people. Given the arid conditions, surface water is scarce, shows large variability, and is an unreliable source of water for drinking and industrial/mining purposes. In such conditions, groundwater has become a strategic resource in the Pilbara region. To date, however, an integrated regional characterization and conceptualization of the occurrence of groundwater resources in this region were missing. This article addresses this gap by integrating disperse knowledge, collating available data on aquifer properties, by reviewing groundwater systems (aquifer types) present in the region and identifying their potential, and propos- ing conceptualizations for the occurrence and functioning of the groundwater systems identifed. Results show that aquifers across the Pilbara Region vary substantially and can be classifed in seven main types: coastal alluvial systems, concealed channel -

The Importance of Western Australia's Waterways

The Importance of Western Australia's Waterways There are 208 major waterways in Western Australia with a combined length of more than 25000 km. Forty-eight have been identified as 'wild rivers' due to their near pristine condition. Waterways and their fringing vegetation have important ecological, economic and cultural values. They provide habitat for birds, frogs, reptiles, native fish and macroinvertebrates and form important wildlife corridors between patches of remnant bush. Estuaries, where river and ocean waters mix, connect the land to the sea and have their own unique array of aquatic and terrestrial flora and fauna. Waterways, and water, have important spiritual and cultural significance for Aboriginal people. Many waterbodies such as rivers, soaks, springs, rock holes and billabongs have Aboriginal sites associated with them. Waterways became a focal point for explorers and settlers with many of the State’s towns located near them. Waterways supply us with food and drinking water, irrigation for agriculture and water for aquaculture and horticulture. They are valuable assets for tourism and An impacted south-west river section - salinisation and erosion on the upper Frankland River. Photo are prized recreational areas. S. Neville ECOTONES. Many are internationally recognised and protected for their ecological values, such as breeding grounds and migration stopovers for birds. WA has several Ramsar sites including lakes Gore and Warden on the south coast, the Ord River floodplain in the Kimberley and the Peel Harvey Estuarine system, which is the largest Ramsar site in the south west of WA. Some waterways are protected within national parks for their ecosystem values and beauty. -

Published Drinking Water Source Protection Assessments, Plans and Land Use and Water

Published drinking water source protection assessments, plans and land use and water management strategies South Coast South West Swan Avon Mid West Goldfields Region Region Region Region Gascoyne Region Angove Creek Catchment Balingup Dam Bickley Reservoir CA1 Coomberdale WR1 Laverton WR1 Area (CA)2 (Padbury Reservoir) CA2 Bolganup Creek Water Bancell Brook CA2 Bindoon – Chittering WR1 Coral Bay WR1 Leonora WR1 Reserve (WR)1 Bremer Bay WR1 (draft) Boyup Brook Dam CA2 Bolgart WR1 Cue WR1 Menzies WR1 Bridgetown (Hester Dam) Brookton-Happy Valley Condingup WR1 Dandaragan WR1 Sandstone WR2 CA2 WR1 Denmark River CA2 Brunswick CA1 Brookton Reservoir CA1 Dathagnoorara WR1 Wiluna WR2 Denham North & South Esperance WR1 Bunbury WR1 Calingiri WR1 Pilbara Region WRs1 Gibson WR1 Busselton WR1 Canning River CA1 Dookanooka WR1 Cane River WR1 Hopetoun WR1 Donnybrook WR1 Churchman Brook CA1 Eneabba WR1 De Grey River WR1 Marbellup CA1 Greenbushes CA2 East Wanneroo UWPCA3 Exmouth WR1 Harding Dam CA1 Northcliffe CA1 Harris Dam CA1 Gingin WR1 Gascoyne Junction WR1 Marble Bar WR1 Millstream WR Quickup River CA2 Harvey Dam CA1 Gnangara UWPCA3 Horrocks Beach WR2 (West Pilbara)1 Ravensthorpe WR2 Kirup Dam CA1 Guilderton WR1 Jurien WR1 Newman WR1 South Coast WR & Leeuwin Springs CA & Lancelin WR1 Kalbarri WR1 Nullagine WR1 Limeburners Creek CA1 Fisher Wellfield WR1 Walpole Weir CA & Lefroy Brook CA2 Ledge Point WR1 Meekathara WR1 Yule River WR1 Butlers Creek Dam CA1 Kwinana Peel Manjimup Dam & Phillips Middle Helena CA3 Mingenew WR1 Kimberley Region Region Creek -

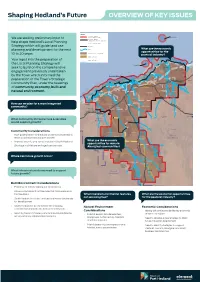

We Are Seeking Preliminary Input to Help Shape Hedland's Local

Shaping Hedland’s Future OVERVIEW OF KEY ISSUES LEGEND Town of Port Hedland Redout Island Local Government Boundary We are seeking preliminary input to Town of Port Hedland Town Planning Scheme No. 5 Boundary help shape Hedland’s Local Planning Local Government Boundary Strategy which will guide land use Key Roads What are the economic planning and development for the next Rivers opportunities for the Pastoral Lease / Station Boundary 10 to 20 years. pastoral industry?North Turtle Island Indigenous Reserve Your input into the preparation of Indigenous Campsite the Local Planning Strategy will Turtle Island seek to build on the comprehensive Ripon Island engagement previously undertaken De Grey Ridley River by the Town which informed the Port Hedland De Grey River preparation of the Town’s Strategic NORT Tjalka Boorda T HERN HIG Y Pardoo GREA HWA Marta Marta Community Plan, under the headings Punju Njamal De Grey of community, economy, built and Tjalka Wara Jinparinya Strelley natural environment. Shaw River South West Pippingara Creek Shelley River Boodarie Peawah River M How can we plan for a more integrated Balla Balla Mundabullangana ARB Turner River LE BAR Wallareenya RO community? Poverty Yule River A Whim Creek Creek D ST COAS TAL WE H Shaw River H IGHWA T Y R Town of O N Port Hedland Lalla Rookh Marble Bar What community infrastructure & services City of Indee Karratha would support growth? North Pole Community Considerations Peawah River Kangan • High quality health and education services essential to Shire of retain population -

Western Australian Natives Susceptible to Phytophthora Cinnamomi

Western Australian natives susceptible to Phytophthora cinnamomi. Compiled by E. Groves, G. Hardy & J. McComb, Murdoch University Information used to determine resistance to P. cinnamomi : 1a- field observations, 1b- field observation and recovery of P.cinnamomi; 2a- glasshouse inoculation of P. cinnamomi and recovery, 2b- field inoculation with P. cinnamomi and recovery. Not Provided- no information was provided from the reference. PLANT SPECIES COMMON NAME ASSESSMENT RARE NURSERY REFERENCES SPECIES AVALABILITY Acacia campylophylla Benth. 1b 15 Acacia myrtifolia (Sm.) Willd. 1b A 9 Acacia stenoptera Benth. Narrow Winged 1b 16 Wattle Actinostrobus pyramidalis Miq. Swamp Cypress 2a 17 Adenanthos barbiger Lindl. 1a A 1, 13, 16 Adenanthos cumminghamii Meisn. Albany Woolly Bush NP A 4, 8 Adenanthos cuneatus Labill. Coastal Jugflower 1a A 1, 6 Adenanthos cygnorum Diels. Common Woolly Bush 2 1, 7 Adenanthos detmoldii F. Muell. Scott River Jugflower 1a 1 Adenanthos dobagii E.C. Nelson Fitzgerald Jugflower NP R 4,8 Adenanthos ellipticus A.S. George Oval Leafed NP 8 Adenanthos Adenanthos filifolius Benth. 1a 19 Adenanthos ileticos E.C. George Club Leafed NP 8 Adenanthos Adenanthos meisneri Lehm. 1a A 1 Adenanthos obovatus Labill. Basket Flower 1b A 1, 7 14,16 Adenanthos oreophilus E.C. Nelson 1a 19 Adenanthos pungens ssp. effusus Spiky Adenanthos NP R 4 Adenanthos pungens ssp. pungens NP R 4 Adenanthos sericeus Labill. Woolly Bush 1a A 1 Agonis linearifolia (DC.) Sweet Swamp Peppermint 1b 6 Taxandria linearifolia (DC.) J.R Wheeler & N.G Merchant Agrostocrinum scabrum (R.Br) Baill. Bluegrass 1 12 Allocasuarina fraseriana (Miq.) L.A.S. Sheoak 1b A 1, 6, 14 Johnson Allocasuarina humilis (Otto & F.