On Frege's Begriffsschrift Notation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

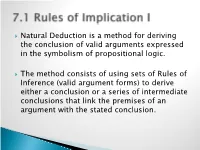

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

Uluslararası Ders Kitapları Ve Eğitim Materyalleri Dergisi

Uluslararası Ders Kitapları ve Eğitim Materyalleri Dergisi The Effect of Artifiticial Intelligence on Society and Artificial Intelligence the View of Artificial Intelligence in the Context of Film (I.A.) İpek Sucu İstanbul Gelişim Üniversitesi, Reklam Tasarımı ve İletişim Bölümü ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO Consumption of produced, quick adoption of discovery, parallel to popularity, our interest in new and different is at the top; We live in the age of technology. A sense of wonder and satisfaction that mankind has existed in all ages throughout human history; it was the key to discoveries and discoveries. “Just as the discovery of fire was the most important invention in the early ages, artificial intelligence is also the most important project of our time.” (Aydın and Değirmenci, 2018: 25). It is the nature of man and the nearby brain. It is Z Artificial Intelligence ”technology. The concept of artificial intelligence has been frequently mentioned recently. In fact, I believe in artificial intelligence, the emergence of artificial intelligence goes back to ancient times. Various artificial intelligence programs have been created and robots have started to be built depending on the technological developments. The concepts such as deep learning and natural language processing are also on the agenda and films about artificial intelligence. These features were introduced to robots and the current concept of “artificial intelligence was reached. In this study, the definition, development and applications of artificial intelligence, the current state of artificial intelligence, the relationship between artificial intelligence and new media, the AI Artificial Intelligence (2001) film will be analyzed and evaluated within the scope of the subject and whether the robots will have certain emotions like people. -

Machine Learning

Graham Capital Management Research Note, September 2017 Machine Learning Erik Forseth1, Ed Tricker2 Abstract Machine learning is more fashionable than ever for problems in data science, predictive modeling, and quantitative asset management. Developments in the field have revolutionized many aspects of modern life. Nevertheless, it is sometimes difficult to understand where real value ends and speculative hype begins. Here we attempt to demystify the topic. We provide a historical perspective on artificial intelligence and give a light, semi-technical overview of prevailing tools and techniques. We conclude with a brief discussion of the implications for investment management. Keywords Machine learning, AI 1Quantitative Researcher 2Head of Research and Development 1. Introduction by the data they are fed—which attempt to find a solution to some mathematical optimization problem. There remains a Machine Learning is the study of computer algorithms that vast gulf between the space of tasks which can be formulated improve automatically through experience. in this way, and the space of tasks that require, for example, – Tom Mitchell (1997) reasoning or abstract planning. There is a fundamental divide Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as one of the most between the capability of a computer model to map inputs to exciting areas of research across nearly every dimension of outputs, versus our own human intelligence [Chollet (2017)]. contemporary digital life. From medical diagnostics to recom- In grouping these methods under the moniker “artificial in- mendation systems—such as those employed by Amazon or telligence,” we risk imbuing them with faculties they do not Netflix—adaptive computer algorithms have radically altered have. -

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus</Em>

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 8-6-2008 Three Wittgensteins: Interpreting the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus Thomas J. Brommage Jr. University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Brommage, Thomas J. Jr., "Three Wittgensteins: Interpreting the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/149 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Three Wittgensteins: Interpreting the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus by Thomas J. Brommage, Jr. A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Kwasi Wiredu, B.Phil. Co-Major Professor: Stephen P. Turner, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Richard N. Manning, J. D., Ph.D. Joanne B. Waugh, Ph.D. Date of Approval: August 6, 2008 Keywords: Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, logical empiricism, resolute reading, metaphysics © Copyright 2008 , Thomas J. Brommage, Jr. Acknowledgments There are many people whom have helped me along the way. My most prominent debts include Ray Langely, Billy Joe Lucas, and Mary T. Clark, who trained me in philosophy at Manhattanville College; and also to Joanne Waugh, Stephen Turner, Kwasi Wiredu and Cahrles Guignon, all of whom have nurtured my love for the philosophy of language. -

Everybody Is Talking About Virtual Assistants, but How Are Users Really Using Them?

Everybody is talking about Virtual Assistants, but how are users really using them? 32nd Human Computer Interaction Conference, July 2018 Dr Marta Pérez García Sarita Saffon López Héctor Donis https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/HCI2018.96 Everybody is talking about Virtual Assistants, but how are users really using them? The 2010s arrived focusing on algorithms of machine learning by enabling computers to have access to large Abstract amounts of data, which comes back to what was expected in the 1950s (Samuel, 1959; Koza, 1996). This Voice activated virtual assistants are growing rapidly in kind of application through a simplified interaction in number, variety and visibility, driven by media coverage, games and hobbies is what enabled the adoption of AI corporate communications, and inclusion in a growing at a user level. What is happening with AI variety of devices. This trend can also be observed by implementation today on our daily basis then? One of how difficult it is becoming to find, among internet many examples of our closest and most frequent users, people who have not used or even heard of this interactions with it is the virtual personal assistants new technology. Having said this, there is a visible (Arafa and Mamdani, 2000). shortage of academic research on this topic. Therefore, in the interest of creating a knowledge base around Regardless of the wave of technology adoption with voice activated virtual assistants based on artificial virtual assistants, little has been written in academia intelligence, this multi-country exploratory research about it so that theory can be built upon. Most study was carried out. -

First Order Logic

Artificial Intelligence CS 165A Mar 10, 2020 Instructor: Prof. Yu-Xiang Wang ® First Order Logic 1 Recap: KB Agents True sentences TELL Knowledge Base Domain specific content; facts ASK Inference engine Domain independent algorithms; can deduce new facts from the KB • Need a formal logic system to work • Need a data structure to represent known facts • Need an algorithm to answer ASK questions 2 Recap: syntax and semantics • Two components of a logic system • Syntax --- How to construct sentences – The symbols – The operators that connect symbols together – A precedence ordering • Semantics --- Rules the assignment of sentences to truth – For every possible worlds (or “models” in logic jargon) – The truth table is a semantics 3 Recap: Entailment Sentences Sentence ENTAILS Representation Semantics Semantics World Facts Fact FOLLOWS A is entailed by B, if A is true in all possiBle worlds consistent with B under the semantics. 4 Recap: Inference procedure • Inference procedure – Rules (algorithms) that we apply (often recursively) to derive truth from other truth. – Could be specific to a particular set of semantics, a particular realization of the world. • Soundness and completeness of an inference procedure – Soundness: All truth discovered are valid. – Completeness: All truth that are entailed can be discovered. 5 Recap: Propositional Logic • Syntax:Syntax – True, false, propositional symbols – ( ) , ¬ (not), Ù (and), Ú (or), Þ (implies), Û (equivalent) • Semantics: – Assigning values to the variables. Each row is a “model”. • Inference rules: – Modus Pronens etc. Most important: Resolution 6 Recap: Propositional logic agent • Representation: Conjunctive Normal Forms – Represent them in a data structure: a list, a heap, a tree? – Efficient TELL operation • Inference: Solve ASK question – Use “Resolution” only on CNFs is Sound and Complete. -

Logic and Ontology

Logic and Ontology Nino B. Cocchiarella Abstract A brief review of the historical relation between logic and ontology and of the opposition between the views of logic as language and logic as calculus is given. We argue that predication is more fundamental than membership and that di¤erent theories of predication are based on di¤erent theories of universals, the three most important being nominalism, conceptualism, and realism. These theories can be formulated as formal ontologies, each with its own logic, and compared with one another in terms of their respective explanatory powers. After a brief survey of such a comparison, we argue that an extended form of conceptual realism provides the most coherent formal ontology and, as such, can be used to defend the view of logic as language. Logic, as Father Bochenski observed, developed originally out of dialectics, rules for discussion and reasoning, and in particular rules for how to argue suc- cessfully.1 Aristotle, one of the founders of logic in western philosophy, described such rules in his Topics, where logic is presented in this way. Indeed, the idea of logic as the art of arguing was the primary view of this subject in ancient philos- ophy. It was defended in particular by the Stoics, who developed a formal logic of propositions, but conceived of it only as a set of rules for arguing.2 Aristotle was the founder not only of logic in western philosophy, but of ontol- ogy as well, which he described in his Metaphysics and the Categories as a study of the common properties of all entities, and of the categorial aspects into which they can be analyzed. -

A Leibnizian Approach to Mathematical Relationships: a New Look at Synthetic Judgments in Mathematics

A Thesis entitled A Leibnizian Approach to Mathematical Relationships: A New Look at Synthetic Judgments in Mathematics by David T. Purser Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy ____________________________________ Dr. Madeline M. Muntersbjorn, Committee Chair ____________________________________ Dr. John Sarnecki, Committee Member ____________________________________ Dr. Benjamin S. Pryor, Committee Member ____________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2009 An Abstract of A Leibnizian Approach to Mathematical Relationships: A New Look at Synthetic Judgments in Mathematics by David T. Purser Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy The University of Toledo May 2010 I examine the methods of Georg Cantor and Kurt Gödel in order to understand how new symbolic innovations aided in mathematical discoveries during the early 20th Century by looking at the distinction between the lingua characterstica and the calculus ratiocinator in the work of Leibniz. I explore the dynamics of innovative symbolic systems and how arbitrary systems of signification reveal real relationships in possible worlds. Examining the historical articulation of the analytic/synthetic distinction, I argue that mathematics is synthetic in nature. I formulate a moderate version of mathematical realism called modal relationalism. iii Contents Abstract iii Contents iv Preface vi 1 Leibniz and Symbolic Language 1 1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………. 1 1.2 Universal Characteristic……………………………………….. 4 1.2.1 Simple Concepts……………………………………….. 5 1.2.2 Arbitrary Signs………………………………………… 8 1.3 Logical Calculus………………………………………………. 11 1.4 Leibniz’s Legacy……………………………………………… 16 1.5 Leibniz’s Continued Relevance………………………………. -

Chapter 10: Symbolic Trails and Formal Proofs of Validity, Part 2

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine CHAPTER 10: SYMBOLIC TRAILS AND FORMAL PROOFS OF VALIDITY, PART 2 Introduction In the previous chapter there were many frustrating signs that something was wrong with our formal proof method that relied on only nine elementary rules of validity. Very simple, intuitive valid arguments could not be shown to be valid. For instance, the following intuitively valid arguments cannot be shown to be valid using only the nine rules. Somalia and Iran are both foreign policy risks. Therefore, Iran is a foreign policy risk. S I / I Either Obama or McCain was President of the United States in 2009.1 McCain was not President in 2010. So, Obama was President of the United States in 2010. (O v C) ~(O C) ~C / O If the computer networking system works, then Johnson and Kaneshiro will both be connected to the home office. Therefore, if the networking system works, Johnson will be connected to the home office. N (J K) / N J Either the Start II treaty is ratified or this landmark treaty will not be worth the paper it is written on. Therefore, if the Start II treaty is not ratified, this landmark treaty will not be worth the paper it is written on. R v ~W / ~R ~W 1 This or statement is obviously exclusive, so note the translation. 427 If the light is on, then the light switch must be on. So, if the light switch in not on, then the light is not on. L S / ~S ~L Thus, the nine elementary rules of validity covered in the previous chapter must be only part of a complete system for constructing formal proofs of validity. -

Laws of Thought and Laws of Logic After Kant”1

“Laws of Thought and Laws of Logic after Kant”1 Published in Logic from Kant to Russell, ed. S. Lapointe (Routledge) This is the author’s version. Published version: https://www.routledge.com/Logic-from-Kant-to- Russell-Laying-the-Foundations-for-Analytic-Philosophy/Lapointe/p/book/9781351182249 Lydia Patton Virginia Tech [email protected] Abstract George Boole emerged from the British tradition of the “New Analytic”, known for the view that the laws of logic are laws of thought. Logicians in the New Analytic tradition were influenced by the work of Immanuel Kant, and by the German logicians Wilhelm Traugott Krug and Wilhelm Esser, among others. In his 1854 work An Investigation of the Laws of Thought on Which are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities, Boole argues that the laws of thought acquire normative force when constrained to mathematical reasoning. Boole’s motivation is, first, to address issues in the foundations of mathematics, including the relationship between arithmetic and algebra, and the study and application of differential equations (Durand-Richard, van Evra, Panteki). Second, Boole intended to derive the laws of logic from the laws of the operation of the human mind, and to show that these laws were valid of algebra and of logic both, when applied to a restricted domain. Boole’s thorough and flexible work in these areas influenced the development of model theory (see Hodges, forthcoming), and has much in common with contemporary inferentialist approaches to logic (found in, e.g., Peregrin and Resnik). 1 I would like to thank Sandra Lapointe for providing the intellectual framework and leadership for this project, for organizing excellent workshops that were the site for substantive collaboration with others working on this project, and for comments on a draft. -

Frege and the Logic of Sense and Reference

FREGE AND THE LOGIC OF SENSE AND REFERENCE Kevin C. Klement Routledge New York & London Published in 2002 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2002 by Kevin C. Klement All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infomration storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klement, Kevin C., 1974– Frege and the logic of sense and reference / by Kevin Klement. p. cm — (Studies in philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-415-93790-6 1. Frege, Gottlob, 1848–1925. 2. Sense (Philosophy) 3. Reference (Philosophy) I. Title II. Studies in philosophy (New York, N. Y.) B3245.F24 K54 2001 12'.68'092—dc21 2001048169 Contents Page Preface ix Abbreviations xiii 1. The Need for a Logical Calculus for the Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 3 Introduction 3 Frege’s Project: Logicism and the Notion of Begriffsschrift 4 The Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 8 The Limitations of the Begriffsschrift 14 Filling the Gap 21 2. The Logic of the Grundgesetze 25 Logical Language and the Content of Logic 25 Functionality and Predication 28 Quantifiers and Gothic Letters 32 Roman Letters: An Alternative Notation for Generality 38 Value-Ranges and Extensions of Concepts 42 The Syntactic Rules of the Begriffsschrift 44 The Axiomatization of Frege’s System 49 Responses to the Paradox 56 v vi Contents 3. -

Boolean Algebra.Pdf

Section 3 Boolean Algebra The Building Blocks of Digital Logic Design Section Overview Binary Operations (AND, OR, NOT), Basic laws, Proof by Perfect Induction, De Morgan’s Theorem, Canonical and Standard Forms (SOP, POS), Gates as SSI Building Blocks (Buffer, NAND, NOR, XOR) Source: UCI Lecture Series on Computer Design — Gates as Building Blocks, Digital Design Sections 1-9 and 2-1 to 2-7, Digital Logic Design CECS 201 Lecture Notes by Professor Allison Section II — Boolean Algebra and Logic Gates, Digital Computer Fundamentals Chapter 4 — Boolean Algebra and Gate Networks, Principles of Digital Computer Design Chapter 5 — Switching Algebra and Logic Gates, Computer Hardware Theory Section 6.3 — Remarks about Boolean Algebra, An Introduction To Microcomputers pp. 2-7 to 2-10 — Boolean Algebra and Computer Logic. Sessions: Four(4) Topics: 1) Binary Operations and Their Representation 2) Basic Laws and Theorems of Boolean Algebra 3) Derivation of Boolean Expressions (Sum-of-products and Product-of-sums) 4) Reducing Algebraic Expressions 5) Converting an Algebraic Expression into Logic Gates 6) From Logic Gates to SSI Circuits Binary Operations and Their Representation The Problem Modern digital computers are designed using techniques and symbology from a field of mathematics called modern algebra. Algebraists have studied for a period of over a hundred years mathematical systems called Boolean algebras. Nothing could be more simple and normal to human reasoning than the rules of a Boolean algebra, for these originated in studies of how we reason, what lines of reasoning are valid, what constitutes proof, and other allied subjects. The name Boolean algebra honors a fascinating English mathematician, George Boole, who in 1854 published a classic book, "An Investigation of the Laws of Thought, on Which Are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities." Boole's stated intention was to perform a mathematical analysis of logic.