Sheela-Na-Gigs and an 'Aesthetics of Damage'.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bawdy Badges and the Black Death : Late Medieval Apotropaic Devices Against the Spread of the Plague

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2012 Bawdy badges and the Black Death : late medieval apotropaic devices against the spread of the plague. Lena Mackenzie Gimbel 1976- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Gimbel, Lena Mackenzie 1976-, "Bawdy badges and the Black Death : late medieval apotropaic devices against the spread of the plague." (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 497. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/497 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BA WDY BADGES AND THE BLACK DEATH: LATE MEDIEVAL APOTROPAIC DEVICES AGAINST THE SPREAD OF THE PLAGUE By Lena Mackenzie Gimbel B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty ofthe College of Arts and Sciences Of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2012 BAWDY BADGES AND THE BLACK DEATH: LATE MEDIEVAL APOTROPAIC DEVICES AGAINST THE SPREAD OF THE PLAGUE By Lena Mackenzie Gimbel B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 A Thesis Approved on April 11, 2012 by the following Thesis Committee: Dr. -

Pagan Spirituality Copy

Pagan Spirituality When t Voice of t Divine i Female What is Paganism??? From the Latin ‘paganus’ “People of the Earth” Paganism is principally rooted in the old religions of Europe, though some adherents also find great worth in the indigenous beliefs of other countries. Such belief in the sacredness of all things can be found world-wide. Pagans see this as their heritage, and retain the beliefs and values of their ancestors in forms adapted to suit modern life. Let’s put this in a little context - it began as something ascribed by the Roman military to indicate civilians, or non-military. From there it was adopted by the general population of Rome and devolved to reflect the non-cosmopolitan - those who followed the old ways, and then, more contemptuously, hillbillies - the unwashed, the uneducated… So - who WERE those people??? Pytagoreans Celebratng te Sunrise 6 BCE Goddess Ancient Mothers Vestonicka Venus Sheela-na-gig Venus of Willendorf 1100 CE 28000 BCE 29000 BCE Venus of Laussel Sleeping Woman of Malta Venus of Lespugue 3300 BCE 20000 BCE 25000 BCE G A I A “Women’s power to create life, apparently out of their own substance, and to respond with fearful and mys9cal blood cycles to the phases of the moon, made them creatures of magic in the eyes of primi9ve men, who knew themselves unable to match such powers. Thus women took on the roles of intermediaries between humanity and spiritual powers. They became seers, priestesses, healers, oracles, lawmakers, judges, and agents of the Great Mother Goddess who gave birth to the universe.” -

Audience and Spatial Experience in the Nuns' Church at Clonmacnoise1

Audience and Spatial Experience in the 1 Nuns’ Church at Clonmacnoise Jennifer Borland Within the ruins of the so-called Nuns’ Church, a twelfth-century building associated with the monastic complex of Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly, Ireland), a weather-beaten acrobatic figure is incorporated into the sculptural decoration of the structure’s interior arch (Figures 1-2). Located on the seventh voussoir of the third arch sandwiched between two chevrons, this figure’s bulbous head and long, splayed legs emphasize the display of her genitals to the viewer. Such a figure might not seem so unusual when considered as one example of the many acrobatic or erotic sculptures that exist on contemporaneous churches across Europe. However, this figure’s location – on an interior arch, and in a space for women – warrants further consideration. Little is known about the Nuns’ Church, in part because of the relative scarcity of historical documents. Nevertheless, some records do indicate that there were buildings for religious women at Clonmacnoise, and scholarly investigations have generally supported this building's association with the patronage of an elite woman named Derbforgaill.2 Although this is by no means certain, there seem to be few concrete reasons to deny that this structure was a space associated with and used by women. This raises the question: what is the relationship between this audience and the acrobatic figure? Although several Borland – Clonmacnoise scholars in recent years have considered the traditional narratives associated with this building, little has been said about the relationship between the audience, the intimate space of this church, and its sculptural decoration. -

Reclaiming the Sheela-Na-Gigs Goddess Imagery in Medieval Sculptures of Lreland

Reclaiming the Sheela-na-gigs Goddess Imagery in Medieval Sculptures of lreland by Ann Pearson serious study of female erotic imagery has been neglected as compared to corresponding investigations of the male Cet article confirme que l'imagerie Sheekz-na-gzgfiitpartie priapic figure. Murray describes the Baubo figure as seated dirne longue tradition lians I'iconographie vulvaire qui est on the ground, with legs spread to display the pudenda connuehtraverslemondcetassurequeknrlte&ladPPssecelte which are exaggerated or clearly indicated. The Baubo- a PtP I'inspiration & ces bas-reliefj. Phyrne version of these sculptures has the figures squat- ting, with knees bent, "frog-like." ~he~ositionofthe arms varies but some repeat the sheela gesture of resting on the Like women, the sheeh have sujgeredfiom the thighs as if to "emphasize the pudenda" (Murray 95). limitations that certain labeh have placed on them. Murray's article discusses a number of sheekz sculptures Irish art historians, prima+ male, insist that the from both England (at Kilpeck, Romsey, Oxford, Whittlesford, and Essex), and Ireland (at Blackhall and sheeh are a variant of medievalgrotesques designed Ballylarkin), as fitting the Egyptian model. She claims that to warn against the sins of the fish. Baubo "belonged to that group of goddesses, such as the Bona Dea, from whose rites men were rigorously ex- cluded" (99). She was for women only and was, "as essen- The small, sexually-specific stone carvings of female fig- tially divine as Isis or Ishtar" (99). As with the sheeh, ures called sheela-na-gigs found on churches and Norman Baubo figures appear in number, suddenly, in a specific towers or castles in Ireland and Britain are an historical historical period seemingly with no precursors, although mystery that has been puzzled over and researched from Murray has suggested that the pubic triangles on more an- seemingly every angle. -

Deusa Sheela Na Gig 5 De Junho, Sexta-Feira, Conexão Às 20H Sugestão: Vestir Saia Ou Vestido De Cor Escura

DECEMBER 2016 Deusa Viva Um informativo do Círculo de Mulheres da Teia de Thea Plenilúnio .:. Junho 2020 .:. nº 251 Sheela Na Gig Guardiã celta do portal da vida e da morte “Eu abro a minha vulva para todos verem Eu a estico bem aberta, pois ela é o portal pelo qual todos entram para a vida. Eu sou a abertura para este mundo, para os sábios e os ignorantes, para os selvagens e os pacatos, para os corajosos e os mansos. Eu sou a Anciã, sou o portal da vida e lhe digo: entre pelo meu portal e abra-se, se tiver algo importante mostre, e assim todos podem ver.” Goddess Oracle. Amy Sophia Marashinsky *Por Mirella Faur C onhecida também como Sila-na-Geige, Sue-ni-Ghig, Sheelah-ni-Gig era um arquétipo celta paradoxal e um tanto quanto nebuloso, representando o aspecto da Deusa como Mãe e Anciã. As suas esculturas figurativas foram encontradas na entrada de igrejas, castelos, portais, muralhas e edifícios na Irlanda (em maior número), Escócia e Grã-Bretanha e geralmente eram colocadas acima de portas, muros e janelas, supostamente para proteger estas aberturas contra os espíritos negativos. O nome sempre foi um enigma para os etimologistas por não se enquadrar nas línguas faladas nas ilhas britânicas e a sua descrição inclui elementos da deusa Cailleach, presente nos mitos irlandeses e escoceses. 1 Há pouca informação escrita a respeito das suas origens, e muito do seu simbolismo foi perdido com a censura religiosa cristã, que ressaltou apenas a sua vulgaridade e obscenidade. Devido a essa perseguição, muitas das suas imagens foram destruídas ou desfiguradas pelos fanáticos cristãos. -

Sheela-Na-Gig: Ilmiö Ja Historia

Whore, Witch, Saint, Goddess? Sheela-na-gig: ilmiö ja historia Ilona Tuomi Johdanto My�häiskeskiajalta peräisin olevat Sheela-na-gig-veistokset ovat viime aikoina vakiinnuttaneet asemansa populaarikulttuurissa. Näistä alastomista naishahmoista on tullut ikoneita niin kirjojen kansiin, koruihin kuin koriste-esineisiinkin, ja niille on Internetissä perustettu lukuisia ’fanisivustoja’1. Taiteilijat noteerasivat Sheelojen taipumuksen ihastuttaa ja vihastuttaa jo tätä ennen, ja Sheelat ovat olleetkin inspiraation lähde sekä kirjallisuudessa, musiikissa että kuvataiteessa.2 Suomalaisille television katsojille Sheelat saattoivat tulla tutuiksi irlantilaisesta televisiosarjasta Ballykissangel. Sarjan jaksossa nimeltä Rock Bottom kylän väkeä hätkähdytti alaston naisveistos, jota arkeologit olivat tulleet noutamaan kylästä tarkempaa tutkimusta varten.3 Mitä Sheela-na-gig-veistokset sitten oikein ovat? A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology kuvaa Sheeloja irlantilaisiksi kiviveistoksiksi, jotka kuvaavat alastonta naista, jonka jalat ovat etäällä toisistaan ja siten paljastavat vaginan (MacKillop 1998, 385). Sheelat ovat tyypillisesti joko seisovassa tai kyykyssä olevassa asennossa, ja usein toinen tai molemmat kädet koskettavat sukupuolielimiä tai ainakin osoittavat niiden suuntaan. Yleensä sukupuolielimiä on painotettu lisäksi liioittelemalla niiden kokoa ja yksityiskohtia. Sheeloja on l�ydetty tusinan verran Länsi-Euroopan eri osista, mutta ylivoimaisesti eniten Brittein saarilta, eritoten Irlannista, jossa veistoksia on yli sata. Suurin osa veistoksista on sijoitettu joko kirkkojen ja luostarien seiniin, lähelle ovea tai ikkunaa, sekä linnojen seiniin ja muureihin. 1 Katso esim. www.sheelanagig.org, www.irelands-sheelanagigs.org/archive, www.beyond- the-pale.org.uk/sheela1.htm, www.bandia.net/sheela/SheelaFront.html ja www. geocities. com/wellesley/1752/sheela.html. Kaikki sivustot luettu 24.7.2009. 2 Esimerkkeinä Nobel-kirjailija Seamus Heaneyn runo Sheelagh na Gig at Kilpeck (Station Island. 1985. -

Abhiyoga Jain Gods

A babylonian goddess of the moon A-a mesopotamian sun goddess A’as hittite god of wisdom Aabit egyptian goddess of song Aakuluujjusi inuit creator goddess Aasith egyptian goddess of the hunt Aataentsic iriquois goddess Aatxe basque bull god Ab Kin Xoc mayan god of war Aba Khatun Baikal siberian goddess of the sea Abaangui guarani god Abaasy yakut underworld gods Abandinus romano-celtic god Abarta irish god Abeguwo melansian rain goddess Abellio gallic tree god Abeona roman goddess of passage Abere melanisian goddess of evil Abgal arabian god Abhijit hindu goddess of fortune Abhijnaraja tibetan physician god Abhimukhi buddhist goddess Abhiyoga jain gods Abonba romano-celtic forest goddess Abonsam west african malicious god Abora polynesian supreme god Abowie west african god Abu sumerian vegetation god Abuk dinkan goddess of women and gardens Abundantia roman fertility goddess Anzu mesopotamian god of deep water Ac Yanto mayan god of white men Acacila peruvian weather god Acala buddhist goddess Acan mayan god of wine Acat mayan god of tattoo artists Acaviser etruscan goddess Acca Larentia roman mother goddess Acchupta jain goddess of learning Accasbel irish god of wine Acco greek goddess of evil Achiyalatopa zuni monster god Acolmitztli aztec god of the underworld Acolnahuacatl aztec god of the underworld Adad mesopotamian weather god Adamas gnostic christian creator god Adekagagwaa iroquois god Adeona roman goddess of passage Adhimukticarya buddhist goddess Adhimuktivasita buddhist goddess Adibuddha buddhist god Adidharma buddhist goddess -

Fascinology in the Society and Literature of the British Isles

Fascinology in the Society and Literature of the British Isles Milagros Torrado Cespón 2011 Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Milagros Torrado Cespón Tese dirixida polo Doutor Fernando Alonso Romero Catedrático de Universidade ISBN 978-84-9887-798-4 (Edición digital PDF) Fascinology in the Society and Literature of the British Isles Milagros Torrado Cespón 2011 Universidade de Santiago de Compostela A doutoranda, Visto e prace do director de tese Milagros Torrado Cespón Doutor Fernando Alonso Romero Acknowledgments In Galicia: Dr. Fernando Alonso Romero, Dr. María Castroviejo Bolíbar, Dr. Cristina Mourón Figueroa, Dr. Luis Rábade Iglesias, José María Costa Lago, Lourdes Cespón Saborido, Lucía Cespón Saborido, Nati Triñanes Cespón, José Manuel Triñanes Romero, Brais Triñanes Triñanes, Ainoa Triñanes Triñanes, Dolores Rodríguez Costa, Jesús Brandón Sánchez, Alberto Piñeiro, Manuel Pose Carracedo, Cecilia Fernández Santomé and Aitor Vázquez Brandón In the Isle of Man: The Centre for Manx Studies, Dr. Peter Davey, Dr Philippa Tomlinson, Dr. Harold Mytum, Dr Fenella Bazin, Dr. Catriona Mackie, Gill Wilson, The Manx Museum, The Manx National Heritage, Wendy Thirkettle, Paul Speller, Jackie Turley, Breesha Maddrew, Kevin Rothwell , Paul Weatherall and Claus Flegel, In England: The British Museum, Museum of London, Geraldine Doyle, Angie Worby and Tom Shoemaker In Scotland: Bill Lockhart In Wales: Tim Gordon and Gwynneth Trace In Ireland: Oisín McGann Thank you all Fascinology in the Society and Literature of the British Isles Milagros Torrado -

Grupos Y Programas Músicas Del Mundo

XXI NOCHES EN LOS JARDINES DEL REAL ALCÁZAR / 2020 grupos y programas músicas del mundo BALSAMIA PÁG. 2 El veneno de la Moriana (La mujer en la tradición sefardí) Nombres de Mujer CANTICA PÁG. 5 Romances de Amor y Muerte. Homenaje a Bécquer 150 Aniversario del fallecimiento de Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer CONFLUENCIAS PÁG. 8 Confluencia de grados MINHA LUA & RICARDO J. MARTINS PÁG. 10 Siempre Amália Centenario del nacimiento de Amália Rodrigues STOLEN NOTES PÁG. 13 La renovación folk de las naciones celtas Produce y programa Días de actuación: 4/8, 12/9 BALSAMIA Clara Campos canto / César Carazo canto y viola / Aníbal Soriano cuerda pulsada / Álvaro Garrido percusión —Videos https://youtu.be/cYifwxmctnc / https://youtu.be/thkaX6nnOVg —El grupo El proyecto musical Balsamia, se plantea como un lugar musical de encuentros, de vivencias y de sensaciones en torno a la interesantísima e histórica cultura sefardí, tan presente en tantos y tantos rincones de nuestro pasado y nuestro presente. Balsamia está liderado por la carismática cantante Clara Campos, una amante de la música y la cultura sefardí, a la que acompañan en el proyecto tres músicos especialistas en músicas del Mediterráneo: El cantante César Carazo, el laudista Aníbal Soriano y el percusionista Álvaro Garrido. —Sinopsis La gran riqueza del repertorio de la música sefardí, es consecuencia de la gran expansión geográfica de la diáspora judía después de la expulsión en 1492. Cuando marcharon forzosamente de España, se llevaron consigo esos romances que a través de su tradición oral han / 2 Produce y programa perdurado. Poco a poco fueron tomando las músicas locales de cada sitio donde llegaron. -

The Sheela-Na-Gig

The Sheela-na-gig: An Inspirational Figure for Contemporary Irish Art Sonya Ines Ocampo-Gooding A Thesis in the Special Individualized Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2012 December 15 © Sonya Ines Ocampo-Gooding, 2012 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Sonya Ines Ocampo-Gooding Entitled: Sheela-na-gig: An Inspirational Figure for Contemporary Irish Art and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _______________________________________________________ Chair Brad Nelson _______________________________________________________ Examiner Pamela Bright _______________________________________________________ Examiner Lorrie Blair _______________________________________________________ Supervisor Elaine Cheasley Paterson Approved by ________________________________________________________ Brad Nelson Graduate Program Director __________________ 2012 ________________________________________ Paula Wood-Adams Interim Dean of Graduate Studies Abstract The Sheela-na-gig: An Inspirational Figure for Contemporary Irish Art Sonya Ines Ocampo-Gooding A Sheela-na-gig is an enigmatic, medieval stone carving of a female figure with exposed genitalia. It is exceptional both as a public -

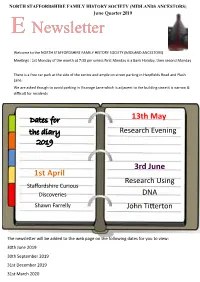

E Newsletter

NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY (MIDLANDS ANCESTORS) June Quarter 2019 E Newsletter Welcome to the NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY (MIDLAND ANCESTORS) Meengs : 1st Monday of the month at 7:30 pm unless First Monday is a Bank Holiday, then second Monday There is a free car park at the side of the centre and ample on street parking in Harpfields Road and Flash Lane. We are asked though to avoid parking in Vicarage Lane which is adjacent to the building since it is narrow & difficult for residents Dates for 13th May the diary Research Evening 2019 3rd June 1st April Research Using Staffordshire Curious Discoveries DNA Shawn Farrelly John Tierton The newsleer will be added to the web page on the following dates for you to view: 30th June 2019 30th September 2019 31st December 2019 31st March 2020 1st April 2019 AGENDA 1. Minutes of last meeng. 2. Chairman’s Report. 3. Secretary’s Report 4. Treasurer’s Report, 5. Elecon of Officers and commiee members (All current members of the commiee are willing to connue but if there are other nominaons we will have a vote. If no other nominaons it goes through unopposed) Chairperson:- Bill Harrison Vice Chairperson:- Derek Cliff Correspondence & Minutes:- Caroline Elson Treasurer:-Derek Cliff Programme Secretary:- Brian Wilson Head Librarian:- Dianne Shenton MI’s Co-Ordinator:- Rob Carter Fiche Librarian:- Mike Griffin Computer Liaison:- Bill Harrison Newsleer Editor:- Rob Carter Recepon:- Joan Cartlidge Branch Webmaster:- Bill Harrison Projects Co-Ordinator:- VACANT Book Sales Officer:- VACANT 6. Proposal to downsize or re-locate the library Since moving from Epworth Street and having access to wi-fi the use of the library has diminished to praccally zero. -

Some Common Features in Irish Gaelic and Hindu Societies Liam SS Réamonn 14/Nodlaig/2006

Paper II Some common Features in Irish Gaelic and Hindu Societies Liam SS Réamonn 14/Nodlaig/2006 [I] Mahatma Ghandi [II] Evidence of Indo-European religious Links between Gaeldom and Hindustan [III] Hindu Evidence of a direct Link with Celts [IV] Folkloric Links [V] Musical Links [VI] The legal Systems [VII] Enduring linguistic Connections [I] Mahatma Ghandi The long-lost comradeship between Celt and Hindu was evidenced when Mahatma Ghandi could say that he took inspiration in bringing about Indian independence from the struggles of the Irish people. Ireland, a country of insignificant extent, had caught the special interest of this great and spiritual leader. Originally the Celtic appearance in Europe, from near the Caspian Sea, came at the same time as another migration into India and Iran. It has been postulated that Proto-Celts and Hindus had common ancestry in the Battle Axe People in southern Russia. Elements of pre-historic art still exist in the ethnic jewellery of India and Ireland. [II] Evidence of Indo-European religious Links between Gaeldom and Hindustan Indo-European ancients, observing nature and drawing from its manifestations, deduced eternal truths with skill and in such manner as to give guidance and true meaning to the lives of generations to come. Gaelic and Hindu sagas are compelling. Hindu, Celtic, Teutonic and Greek mythologies contain the same conceptual groundwork. The powers of nature are given human form. Vedic brahmans and Celtic, Norse and Latin poets taught that the sky, sun, moon, earth, mountains, forests, seas and underworld were ruled by beings like their own temporal leaders but more powerful and subject to higher authority.