Design Guide 1.2 Area Covered by the Design Guide 1.3 the National Park 1.4 Planning Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With St. Peter's, Hebden

With St. Peter’s, Hebden Annual Parochial Church Meeting 15th November 2020 Reports Booklet The Parish of Linton St. Michael’s & All Angels, Linton St. Peter’s, Hebden Church Officials Rector Rev David Macha Reader Cath Currier PCC Secretary Vacancy Church Wardens Rory Magill Helen Davy Mark Ludlum Valerie Ludlum Treasurer Maureen Chaduc Deanery Synod Representatives Lesley Brooker Jennie Scott Lay Members Neil McCormac Betty Hammonds Jane Sayer Jacqui Sugden + 5 Vacancies Sidespersons Rita Clark Ian Clark Betty Hammonds Dennis Leeds Bunty Leder Valerie Ludlum Phyllida Oates Bryan Pearson Pamela Whatley-Holmes John Wolfenden Joan Whittaker Muriel White Brian Metcalfe Mary Douglas Ian Simpson The Parish of Linton St. Michael’s & All Angels, Linton St. Peter’s, Hebden Meeting of Parishioners – 15th November 2020 Agenda Minutes of Meeting of Parishioners 2019 Election of Churchwardens Annual Parochial Church Meeting – 15th November 2020 Agenda 1 Apologies for absence 2 Reception of the Electoral Roll 3 Election of Laity to the Parochial Parish Council and to the Deanery Synod 4 Appointment of Sidepersons 5 Approval of 2019 APCM Minutes 7 2019 Annual Accounts – Receipt of and Acceptance of Independent Examiner’s Statement for 2019 accounts 8 Annual Reports in booklets 9 Chairman’s Address 10 AOB & Questions Electoral Roll Information at 6th October 2020 There are 64 names on the Electoral Roll for 2020. This is an increase of one from 2019 and comprises 55 resident in the parish and 9 not resident in the parish. The electronic publication of the Electoral Roll on the Linton parish website undoubtedly contributed to the low level of revisions and no removals were notified. -

Download Our Brochure

About The Red Lion... A Warm Family Welcome Before the bridge was built, the buildings where the Red Lion now stands were situated on a ford across the River Wharfe. When the river was in spate, these buildings offered refuge & temporary lodgings to those who could not cross. In the 16th Century, the permanent buildings you see now began to arise and the Ferryman’s Inn orignally entitled ‘Bridge Tavern’ became the beautiful country Inn which is now the Red Lion. Bought by Elizabeth & Andrew Grayshon in 1991, The Red Lion & Manor House has now passed into the capable hands of their four daughters - Sarah, Victoria, Katy & Eleanor, who, with their husbands & families, continue to provide visitors with the same service that has kept the Red Lion as one of the most popular destinations in the Dales. • Breathtaking scenery • Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty • Grade II listed building Stay A While... The Manor House & Red Lion Holiday Cottages In addition to the rooms in the Red Lion, we have 11 B&B rooms in the Manor House - a charming Victorian property 150 yards away - and 4 holiday cottages. Perfect for overnight accommodation, the Manor House bedrooms are modern but simple most having lovely views of the River Wharfe and village. Perched on the banks of the River Wharfe, the 4 Riverside holiday cottages have quirky ‘upside down’ living accommodation; double & twin bedrooms on the ground floor; kitchen, dining and sitting rooms on the first floor with views down the river and to the fell. The kitchens are complete with quality appliances including a dishwasher, fridge/freezer, washing machine and microwave. -

Grade 2 Listed Former Farmhouse, Stone Barns

GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an Rare development opportunity in a soughtafter location. Situation Swale Farmhouse is well situated, lying within a soughtafter and accessible location occupying an elevated position within Swaledale. The property is approached from a private driveway to the south side of the B6260 Richmond to Reeth Road approximately 8 miles from Richmond, 3 miles from Reeth and 2 miles from Grinton. Description Swale Farmhouse is a Grade 2 listed traditional stone built farmhouse under a stone slate roof believed to date from the 18th Century with later 19th Century alterations. Formerly divided into two properties with outbuildings at both ends the property now offers considerable potential for conversion and renovation to provide a beautifully situated family home or possibly multiple dwellings (subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents). The house itself while needing full modernisation benefits from well-proportioned rooms. The house extends to just over 3,000 sq ft as shown on the floorplan with a total footprint of over 7,000 sq ft including the adjoining buildings. The property has the benefit of an adjoining grass paddock ideal for use as a pony paddock or for general enjoyment. There are lovely views from the property up and down Swaledale and opportunities such as this are extremely rare. General Information Rights of Way, Easements & Wayleaves The property is sold subject to, and with the benefit of all existing wayleaves, easements and rights of way, public and private whether specifically mentioned or not. -

Contracts Awarded Sep 14 to Jun 19.Xlsx

Contracts, commissioned activity, purchase order, framework agreement and other legally enforceable agreements valued in excess of £5000 (January - March 2019) VAT not SME/ Ref. Purchase Contract Contract Review Value of reclaimed Voluntary Company/ Body Name Number order Title Description of good/and or services Start Date End Date Date Department Supplier name and address contract £ £ Type Org. Charity No. Fairhurst Stone Merchants Ltd, Langcliffe Mill, Stainforth Invitation Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 1 PO113458 Stone supply for Brackenbottom project Supply of 222m linear reclaimed stone flags for Brackenbottom 15/07/2014 17/10/2014 Rights of Way Road, Langcliffe, Settle, North Yorkshire. BD24 9NP 13,917.18 0.00 To quote SME 7972011 Hartlington fencing supplies, Hartlington, Burnsall, Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 2 PO113622 Woodhouse bridge Replacement of Woodhouse footbridge 13/10/2014 17/10/2014 Rights of Way Skipton, North Yorkshire, BD23 6BY 9,300.00 0.00 SME Mark Bashforth, 5 Progress Avenue, Harden, Bingley, Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 3 PO113444 Dales Way, Loup Scar Access for all improvements 08/09/2014 18/09/2014 Rights of Way West Yorkshire, BD16 1LG 10,750.00 0.00 SME Dependent Historic Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 4 None yet Barn at Gawthrop, Dent Repair works to Building at Risk on bat Environment Ian Hind, IH Preservation Ltd , Kirkby Stephen 8,560.00 0.00 SME 4809738 HR and Time & Attendance system to link with current payroll Carval Computing Ltd, ITTC, Tamar Science Park, -

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Self-Guided Walking Destinations: Yorkshire Dales & England Trip code: MDPXA-7 1, 2, 3 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Enjoy a festive break in the Yorkshire Dales with the walking experts; we have all the ingredients for your perfect self-guided escape. Newfield Hall, in beautiful Malhamdale, is geared to the needs of walkers and outdoor enthusiasts. Enjoy hearty local food, detailed route notes, and an inspirational location from which to explore this beautiful national park. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The use of our Discovery Point to plan your walks – maps and route notes available www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Use our Discovery Point, stocked with maps and walks directions, for exploring the local area • Head out on any of our walks to discover the varied landscape of the Southern Yorkshire Dales on foot • Enjoy magnificent views from impressive summits • Admire green valleys and waterfalls on riverside strolls • Marvel at the wild landscape of unbroken heather moorland and limestone pavement • Explore quaint villages and experience the warm Yorkshire hospitality at its best • Choose a relaxed pace of discovery and get some fresh air in one of England's most beautiful walking areas • Explore the Yorkshire Dales by bike • Ride on the Settle to Carlisle railway • Visit the spa town of Harrogate TRIP SUITABILITY Explore at your own pace and choose the best walk for your pace and ability. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

3. Minutes of GPC Meeting 8 June 2021.Docx

1 Giggleswick Parish Council Minutes of Meeting 3, held on 8th June 2021 15 Minutes for public participation session There were no members of the public in attendance. 3.1 Present: Cllrs Perrings (Chairman), Jones (Vice-Chairman), Airey, Bradley, Coleman, Davidson, Ewin-Newhouse, and Williamson. In attendance: County Cllr David Staveley, District Cllr Robert Ogden and Parish Council Clerk Marijke Hill. Apologies received from Cllr. Greenhalgh. 3.2 Code of Conduct and Declaration of Interests a. Councillors did not record any Disclosable Pecuniary Interests (DPI) or Other Interests in relation to items on this agenda. b. No requests were made for dispensation in connection with any items on this agenda. 3.3 Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the Parish Council and Meeting 2, both held remotely on 4th May 2021 The Council resolved that the minutes of the Annual Meeting of the Parish Council and Meeting 2, both held remotely on 4th May 2021 should be confirmed and signed by the Chairman, Cllr Perrings, as a true and accurate record. 3.4 Matters from previous meetings not otherwise included on the agenda The Council reported no matters from previous meetings not otherwise included on the agenda. 3.5 Reports from County and District Councillor and North Yorkshire Police The Chairman welcomed Craven District Councillor Robert Ogden. Cllr David Staveley reported on CDC matters about the issues of waste collection from the Harrison Playing Fields and the installation of an additional waste bin near the entrance / exit at the south end of the Lower Fellings at item 3.7a. The Council noted the NYP incidents report from 5 May to 8 June, in which 24 incidents were reported, notably a non injury RTC at Four Lane ends and theft of roof tiles on Yealand Avenue. -

Parish of Kirkby Malghdale*

2 44 HISTORY OF CRAVEX. PARISH OF KIRKBY MALGHDALE* [HIS parish, at the time of the Domesday Survey, consisted of the townships or manors of Malgum (now Malham), Chirchebi, Oterburne, Airtone, Scotorp, and Caltun. Of these Malgum alone was of the original fee of W. de Perci; the rest were included in the Terra Rogeri Pictaviensis. Malgum was sur veyed, together with Swindene, Helgefelt, and Conningstone, making in all xn| car. and Chircheby n car. under Giggleswick, of which it was a member. The rest are given as follows :— 55 In Otreburne Gamelbar . in car ad glct. 55 In Airtone . Arnebrand . mi . car ad glct. 55 In Scotorp Archil 7 Orm . in . car ad glct. •ii T "i 55 In Caltun . Gospal 7 Glumer . mi . car ad giet. Erneis habuit. [fj m . e in castell Rog.f This last observation applies to Calton alone. The castellate of Roger, I have already proved to be that of Clitheroe; Calton, therefore, in the reign of the Conqueror, was a member of the honour of Clitheroe. But as Roger of Poitou, soon after this time, alienated all his possessions in Craven (with one or two trifling exceptions) to the Percies, the whole parish, from the time of that alienation to the present, has constituted part of the Percy fee, now belonging to his Grace the Duke of Devonshire. \ [* The parish of Kirkby: in-Malham-Dale, as it is now called, contains the townships of Kirkby-Malham, Otterburn, Airton, Scosthrop, Calton, Hanlith, Malham Moor, and Malham. The area, according to the Ordnance Survey, is -3,777 a- i r- 3- P- In '871 the population of the parish was found to be 930 persons, living in 183 houses.] [f Manor.—In Otreburne (Otterburn) Gamelbar had three carucates to be taxed. -

Ingleton National Park Notes

IngletonNational Park Notes Don’t let rain stop play The British weather isn’t all sunshine! But that shouldn’t dampen your enjoyment as there is a wealth of fantastic shops, attractions and delicious food to discover in the Dales while keeping dry. Now’s the time to try Yorkshire curd tart washed down with a good cup of tea - make it your mission to seek out a real taste of the Dales. Venture underground into the show caves at Stump Cross, Ingleborough and White Scar, visit a pub and sup a Yorkshire pint, or learn new skills - there are workshops throughout the Star trail over Jervaulx Abbey (James Allinson) year at the Dales Countryside Museum. Starry, starry night to all abilities and with parking and other But you don’t have to stay indoors - mountain Its superb dark skies are one of the things that facilities, they are a good place to begin. biking is even better with some mud. And of make the Yorkshire Dales National Park so What can I see? course our wonderful waterfalls look at their special. With large areas completely free from very best after a proper downpour. local light pollution, it's a fantastic place to start On a clear night you could see as many as 2,000 your stargazing adventure. stars. In most places it is possible to see the Milky Way as well as the planets, meteors - and Where can I go? not forgetting the Moon. You might even catch Just about anywhere in the National Park is great the Northern Lights when activity and conditions for studying the night sky, but the more remote are right, as well as the International Space you are from light sources such as street lights, Station travelling at 17,000mph overhead. -

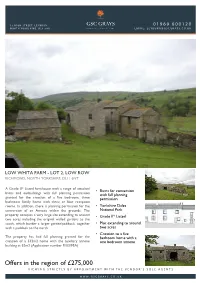

Offers in the Region of £275,000 Viewing Strictly by Appointment with the Vendor’S Sole Agents

15 HIGH STREET, LEYBURN 01969 600120 NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL8 5AQ EMAIL: [email protected] LOW WHITA FARM - LOT 2, LOW ROW RICHMOND, NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL11 6NT A Grade II* Listed farmhouse with a range of attached • Barns for conversion barns and outbuildings with full planning permission with full planning granted for the creation of a five bedroom, three permission bathroom family home with three or four reception rooms. In addition, there is planning permission for the • Yorkshire Dales conversion of an Annexe within the grounds. The National Park property occupies a very large site extending to around • Grade II* Listed two acres including the original walled gardens to the south, which border a larger garden/paddock, together • Plot extending to around with a paddock to the north. two acres • Creation to a five The property has had full planning granted for the bedroom home with a creation of a 332m2 home with the auxiliary annexe one bedroom annexe building at 62m2 (Application number R/03/95A) Offers in the region of £275,000 VIEWING STRICTLY BY APPOINTMENT WITH THE VENDOR’S SOLE AGENTS WWW. GSCGRAYS. CO. UK LOW WHITA FARM - LOT 2, LOW ROW RICHMOND, NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL11 6NT SITUATION AND AMENITIES The farmhouse is situated in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales National Park in Swaledale, on the southern side of the River Swale. The property is equi-distant between Healaugh and Low Row. The town of Reeth is situated approximately 5 miles away which is well served with a primary school, Doctors' survery, local shop, tea rooms, public houses and the Dales Bike Centre. -

The Middleham Herald Coronavirus 2

MMiiddddlleehhaamm HHeerraalldd Second Coronavirus Edition, 8th April 2020 ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ This Middleham Herald has been produced and distributed in line with current Royal Volunteering in Middleham Mail delivery measures. If you would prefer Firstly, a big thank you to everyone who has to receive future editions by e-mail, please got in touch and offered to help other contact the Town Clerk with both your e-mail residents with shopping, collecting and postal addresses. prescriptions, telephone chats etc. We have From the Mayor had several requests for support and have Following the wettest February on record allocated a nearby volunteer to each one. and extensive flooding we now face a deadly We expect there will be more help needed as virus and all the challenges that brings to things progress, so please do not think we everyday life in our community. have forgotten you if you haven’t yet heard We have been heartened by offers of help back from us. We are also linked into the from many residents to assist any who need Community Hubs and the larger councils support at this very difficult time, many who will also refer requests for help to us. thanks to all who have offered. Many These systems are joining up now. If you feel residents have expressed concerns about you now need some practical help, or just a second homes being used in the crisis. We chat on the phone, please do not be afraid to are exploring all avenues to persuade visitors ask – there are friendly people within to stay at home until the lockdown is lifted Middleham whom we know, who are waiting and the police are supporting the measures to step up to help. -

Booking Form

Please retain this section for your records Booking Form Tel: 01756 761236 Please complete and return to: e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.scargillmovement.org The Administrator, Scargill House, Kettlewell, Skipton, North Yorkshire, BD23 5HU Registered charity number 1127838 Tel: 01756 761236 e-mail: [email protected] TERMS and CONDITIONS PLEASE USE BLOCK LETTERS PAYMENT Residential stays require a non-refundable deposit with the booking of Name of Holiday / conference / private retreat £50 per adult and £20 per child. The balance of the fees is required by 4 weeks before arrival. Day events are paid in full at the time of booking. Bookings are not complete until you have received confirmation from the Scargill Movement. Booking Code FEES Arrival Date Departure Date The programme brochure contains the current fees as well as other relevant information in the ‘How to book’ section. Rev/Mr/Mrs/Ms/Miss/Other (please specify) For those otherwise unable to come, our bursary fund may subsidise the Surname cost of visiting. Please ask for details. Christian Name All fees are correct at the time of going to press. However, we reserve the right to amend them without notice prior to the receipt of a booking. Spouse / Friend (with whom you would like to share a room) Prices include VAT where applicable. We reserve the right to alter prices to reflect any change in the VAT rate. Age group 18-20 31-40 51-60 71-80 CANCELLATION Sadly, we have to apply charges for all cancellations. These charges for 21-30 41-50 61-70 81 and over individuals are: Other member(s) of party / children (with ages at time of visit) * Within 4 weeks of arrival - 50% of full fees * Within 2 weeks of arrival - 75% of full fees * Within 1 week of arrival - full fees Substitutions and transfers We are unable to allow substitutions as we often run a waiting list and therefore reserve the right to reallocate beds freed by cancellations.