Shaping Urbanization for Children: a Handbook on Child-Responsive Urban Planning UNICEF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Flushing Meadows Corona Park Strategic Framework Plan

Possible reconfiguration of the Meadow Lake edge with new topographic variation Flushing Meadows Corona Park Strategic Framework Plan 36 Quennell Rothschild & Partners | Smith-Miller + Hawkinson Architects Vision & Goals The river and the lakes organize the space of the Park. Our view of the Park as an ecology of activity calls for a large-scale reorganization of program. As the first phase in the installation of corridors of activity we propose to daylight the Flushing River and to reconfigure the lakes to create a continuous ribbon of water back to Flushing Bay. RECONFIGURE & RESTORE THE LAKES Flushing Meadows Corona Park is defined by water. Today, the Park meets Flushing Bay at its extreme northern channel without significantly impacting the ecological characteristics of Willow and Meadow Lakes and their end. At its southern end, the Park is dominated by the two large lakes, Willow Lake and Meadow Lake, created for shorelines. In fact, additional dredged material would be valuable resource for the reconfiguration of the lakes’ the 1939 World’s Fair. shoreline. This proposal would, of course, require construction of a larger bridge at Jewel Avenue and a redesign of the Park road system. The hydrology of FMCP was shaped by humans. The site prior to human interference was a tidal wetland. Between 1906 and 1934, the site was filled with ash and garbage. Historic maps prior to the ‘39 Fair show the Flushing To realize the lakes’ ecological value and their potential as a recreation resource with more usable shoreline and Creek meandering along widely varying routes through what later became the Park. -

Tomorrow's World

Tomorrow’s World: The New York World’s Fairs and Flushing Meadows Corona Park The Arsenal Gallery June 26 – August 27, 2014 the “Versailles of America.” Within one year Tomorrow’s World: 10,000 trees were planted, the Grand Central Parkway connection to the Triborough Bridge The New York was completed and the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge well underway.Michael Rapuano’s World’s Fairs and landscape design created radiating pathways to the north influenced by St. Peter’s piazza in the Flushing Meadows Vatican, and also included naturalized areas Corona Park and recreational fields to the south and west. The Arsenal Gallery The fair was divided into seven great zones from Amusement to Transportation, and 60 countries June 26 – August 27, 2014 and 33 states or territories paraded their wares. Though the Fair planners aimed at high culture, Organized by Jonathan Kuhn and Jennifer Lantzas they left plenty of room for honky-tonk delights, noting that “A is for amusement; and in the interests of many of the millions of Fair visitors, This year marks the 50th and 75th anniversaries amusement comes first.” of the New York World’s Fairs of 1939-40 and 1964-65, cultural milestones that celebrated our If the New York World’s Fair of 1939-40 belonged civilization’s advancement, and whose visions of to New Dealers, then the Fair in 1964-65 was for the future are now remembered with nostalgia. the baby boomers. Five months before the Fair The Fairs were also a mechanism for transform- opened, President Kennedy, who had said, “I ing a vast industrial dump atop a wetland into hope to be with you at the ribbon cutting,” was the city’s fourth largest urban park. -

Community: a Collaborative Prospective to Curatorial Practices

COMMUNITY: A COLLABORATIVE PROSPECTIVE TO CURATORIAL PRACTICES A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A ^ In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree MOSST * Master of Arts In Museum Studies by Crystal Renee Taylor San Francisco, California May 2015 Copyright by Crystal Renee Taylor 2015 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Community: A Collaborative Prospective to Curatorial Practices by Crystal Renee Taylor, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Museum Studies at San Francisco State University. rward Luby, Ph.D. Director of Museum Studies & _______________________ <i.ren Kienzle, MA Jecturer of Museum Studies ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to dedicate this thesis to my wonderful parents Albert and Frances Taylor who have always supported and encouraged me in all aspects of my life. Also, to Nathaniel who has been a great source of encouragement throughout this process I truly appreciate and thank you. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures................................................................................................................................vii List of Appendices.......................................................................................................................viii Chapter 1: Introduction................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Literature -

Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide INTRODUCTION . .2 1 CONEY ISLAND . .3 2 OCEAN PARKWAY . .11 3 PROSPECT PARK . .16 4 EASTERN PARKWAY . .22 5 HIGHLAND PARK/RIDGEWOOD RESERVOIR . .29 6 FOREST PARK . .36 7 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK . .42 8 KISSENA-CUNNINGHAM CORRIDOR . .54 9 ALLEY POND PARK TO FORT TOTTEN . .61 CONCLUSION . .70 GREENWAY SIGNAGE . .71 BIKE SHOPS . .73 2 The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System ntroduction New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (Parks) works closely with The Brooklyn-Queens the Departments of Transportation Greenway (BQG) is a 40- and City Planning on the planning mile, continuous pedestrian and implementation of the City’s and cyclist route from Greenway Network. Parks has juris- Coney Island in Brooklyn to diction and maintains over 100 miles Fort Totten, on the Long of greenways for commuting and Island Sound, in Queens. recreational use, and continues to I plan, design, and construct additional The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway pro- greenway segments in each borough, vides an active and engaging way of utilizing City capital funds and a exploring these two lively and diverse number of federal transportation boroughs. The BQG presents the grants. cyclist or pedestrian with a wide range of amenities, cultural offerings, In 1987, the Neighborhood Open and urban experiences—linking 13 Space Coalition spearheaded the parks, two botanical gardens, the New concept of the Brooklyn-Queens York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Greenway, building on the work of Museum, the New York Hall of Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, Science, two environmental education and Robert Moses in their creations of centers, four lakes, and numerous the great parkways and parks of ethnic and historic neighborhoods. -

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) Presents Do Ho Suh: 348 West 22Nd Street Showcasing a Recent Gift to the Museum

Image caption on page 3 The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Do Ho Suh: 348 West 22nd Street showcasing a recent gift to the museum. 348 West 22nd Street, Apartment A, Unit-2, Staircase (2011–15) replicates the artist’s ground-floor residence from a New York City building. Created in luminous swaths of translucent polyester, the rooms and hallways are supported by stainless-steel. In this immersive passageway of conjoined rooms, visitors pass through an ephemeral representation of the artist’s personal history. The corridor, stairs, apartment, and studio are each rendered in a single block of color, with fixtures and appliances replicated in exacting detail. Fusing traditional Korean sewing techniques with digital modeling tools, the maze-like installation of 348 West 22nd Street balances intricate construction with delicate monumentality. The installation is curated by Meghan Doherty, Curatorial Assistant, Contemporary Art at LACMA. Inspired by his own history of migration, Suh’s ethereal, malleable architecture presents an intimate world both deeply familiar and profoundly estranged. The artist’s works elicit a physical manifestation of memory, exploring ideas of personal history, cultural tradition, and belief systems in the contemporary world. Best known for his full-size fabric reconstructions of places he has lived including former residences in Seoul, Providence, New York, Berlin, and London, Suh’s creations of physicalized memory address issues of home, displacement, individuality, and collectivity, articulated through the architecture of domestic space. 348 West 22nd Street, Apartment A, Unit-2, Staircase is the second work by Do Ho Suh to enter LACMA’s collection, following the artist’s Gate (2005) which was acquired by the museum in 2006. -

Jul 11 Aug 18 2016 Jun 1 (Deadline) Summer Youth

Summer Youth Arts Project 2016 Jul 11 A free summer program Aug 18 2016 Jun 1 (deadline) Queens middle school students, thinking about your summer? How about: • Spending your summer at a world- class art museum? • Working closely and learning from professional artists? • Developing your arts, academic and social skills through fun art projects and workshops? • Going on art field trips around NYC • Exhibiting your work in a two- week public exhibition and celebration at the Queens Museum in September. • Learning about high school art programs at the Queens Museum and around NYC In this intensive six-week summer arts program, How will the participants be selected? How do I apply? you will grow your art skills in drawing, sculpture, We’ll be looking for youth who Complete your application form online: graphics and much more. You’ll grow as an artist and • Commit to ALL the dates of the program. queensmuseum.org/summer-youth-arts-project learn about how other artists think and create. This • Are OPEN-MINDED and willing to try new is a great opportunity for students who might be things. We strongly encourage applicants to apply online. interested in applying to high schools arts programs. • Are MOTIVATED to grow as artists. Or mail or fax your completed application to Dates Important program details SYAP Education • Mondays to Thursdays, 10AM-5PM • This program is FREE for all admitted Queens Museum • July 11 to August 18 (six weeks) students participants, including art supplies NYC Building • Students will also have access to additional and materials. Flushing Meadows Corona Park optional studio time at the Museum. -

About the Queens Museum the Queens Museum Is a Public Museum Situated Within the Second Largest About the Public Park in New York City

About the Queens Museum The Queens Museum is a public museum situated within the second largest About the public park in New York City. Since its founding in 1972, the Museum has been a home for the production and presentation of great art, intimately Queens Museum connected to its community and to the history of its site. Artist- and community- led projects, some of the most radical and engaged museum education and public programs in the country, and ground-breaking exhibitions are at the core of the Queens Museum’s diverse initiatives. With more than 150 different languages spoken in Queens, the Museum is set amidst the most ethnically diverse locale in the world. What is hyper- local here, therefore, is inherently and profoundly connected to locations and circumstances around the globe. Making vivid the links between that which is locally relevant and internationally imperative through culture and art is vital for the Queens Museum, a way of being that has its roots in the physical history its building. Housed in the historic New York City Building, the City’s official pavilion during the 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs, the Museum’s galleries overlook the Unisphere, the monumental steel globe that remains both a well-known symbol of the 1964 World’s Fair and an enduring symbol of the borough. From 1946 to 1950, our building was home to the United Nations General Assembly. World historic events took place here, from the partition of Korea to the partition of Palestine. U.S. Presidents from Harry S. Truman to John F. -

My Community-To Not Woodhaven Queens 11421 Bandshell Restaurants Music Venues Y Not Sure Y Feel Like I Have to Go Elsewhere

Represent for Your Community Activity 1. Where do you Live 2. What are your favorite Arts and Culture Spots 3. Does your Neighborhood Have... 5. Anything else? Express yourself. a) How are you most likely to find out about arts and culture Do you go to those places/enjoy events? b) How many arts and/or culture events do you attend a month? c) What would malke you those activities? Why or Why not? more likely to attend more arts and culture events than you normally do? d) Are you an artist or 6. If you were in charge of the budget for Places to Hang Places to be Borough Zipcode Neighborhood Neighborhood Borough All of NYC Activities (Y/N) What programs, places or activities from arts organization? If so, please let us know your discipline or your organization) e) Do you arts and culture in NYC, what's the one (Y/N) creative (Y/N) would you most like to add or bring want to join the Northern Manhattan Arts and Culture email list? (You do not need to be an artist or thing you would fund? back? 4. What is in your neighborhood that you arts organization in order to be updatedon the progress of this organization! We would love to can't find anywhere else? keep everyone informed.) If yes, what is your email address. Manhattan La Mama, all of 4th The Kraine, Under Central Park Y Y Y Yes, because I want to live full life and Diversity in Manhattan on LES, though it is Civil service, non profit, artist job program + more equity in funding. -

Venues with Free Or Suggested Admission

The City of New York is home to more than 700 galleries, 380 nonprofit theater companies, 330 dance companies, 131 museums, 96 orchestras, 40 Broadway theaters, 15 major concert halls, five zoos, five botanical gardens, and an aquarium. Many institutions offer free hours or suggested admission. Venues with Free or Suggested Admission • Alice Austen House Museum | www.aliceausten.org • American Folk Art Museum | www.folkartmuseum.org • American Institute of Graphic Arts National Design Center | www.aiga.org • American Museum of Natural History | www.amnh.org • Aperture Foundation Gallery | www.aperture.org • BRIC Rotunda Gallery | www.bricartsmedia.org • Brooklyn Museum | www.brooklynmuseum.org • Bronx Museum of the Arts | www.bronxmuseum.org • The Center for Book Arts | www.centerforbookarts.org • CUE Art Foundation | www.cueartfoundation.org • Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts | www.efanyc.org • Flushing Town Hall | www.flushingtownhall.org • Horticultural Society of New York | www.hsny.org • International Print Center New York | www.ipcny.org • Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning | www.jcal.org • Kentler International Drawing Space | www.kentlergallery.org • King Manor Museum | www.kingmanor.org • Lefferts Historic House | www.prospectpark.org/lefferts • Longwood Art Gallery at Hostos Community College | www.bronxarts.org/lag.asp • Metropolitan Museum of Art / The Cloisters | www.metmuseum.org • MoMA PS1 | www.momaps1.org • El Museo del Barrio | www.elmuseo.org • Museum of Biblical Art | www.mobia.org • Museum of the City of New York -

The Case of Philip Johnson's New York State Pavilion at the 1964-1965 World's Fair

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation January 2004 Complexities in Conservation of a Temporary Post-War Structure: The Case of Philip Johnson's New York State Pavilion at the 1964-1965 World's Fair Susan Singh University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Singh, Susan, "Complexities in Conservation of a Temporary Post-War Structure: The Case of Philip Johnson's New York State Pavilion at the 1964-1965 World's Fair" (2004). Theses (Historic Preservation). 59. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/59 Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2004. Advisor: Lindsay D. A. Falck This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/59 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Complexities in Conservation of a Temporary Post-War Structure: The Case of Philip Johnson's New York State Pavilion at the 1964-1965 World's Fair Comments Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2004. Advisor: Lindsay D. A. Falck This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/59 COMPLEXITIES IN CONSERVATION OF A TEMPORARY POST-WAR STRUCTURE: THE CASE OF PHILIP JOHNSON’S NEW YORK STATE PAVILION AT THE 1964-65 WORLD’S FAIR Susan Singh A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfi llment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2004 ___________________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Reader Lindsay Falck David G. -

Panorama of the City of New York on Long-Term View

Builders of the Panorama Sizes of the Panorama Queens Museum Panorama New York City Building The model was conceived by Robert Moses Approximate size of Manhattan – 70 x 15’ Flushing Meadows Corona Park and constructed by Lester & Associates of Approximate size of Bronx – 40 x 40’ Panorama On Queens, NY 11368 Fun Facts West Nyack, N.Y. It was paid for by New Approximate size of Brooklyn – 50 x 50’ York City. Approximate size of Queens – 60 x 75’ T 718 592 9700 F 718 592 5778 Statue of Liberty – 1 7/8” w/base 3 1/4” E [email protected] Original Purpose of the Panorama: The Central Park – 27 ¾” x 11’ 3 ¼” of the City of Long-Term Panorama was built as New York City’s Verrazano-Narrows Bridge – 5’ 11 ½” x 1”, queensmuseum.org display at the 1964–1965 World’s Fair. After tower height 7” @QueensMuseum the Fair it served as an urban planning tool. Citicorp (Queens) – 6 ¾” (H) Dates of Construction: July 1961–April 1964 Brooklyn Bridge – 3’ 5 ¼” x 1”, New York View tower height 3” Number of workers: It took more than 100 George Washington Bridge – 4 x 11/16”, full-time workers to construct the Panorama. tower height 6” Staten Island Ferry Ride – 22’ Cost: $672,662.69 in 1964 U.S. Dollars Coney Island Beach – 13’ 4 ¼” Updates: The Panorama was designed to Queens Museum, N.Y.C. Building – 4 ¼”x stay current with the changing city. 2 1/8, Height ½” Complete updates took place in 1967, 1968, Empire State Building – 15” 1969, and 1974. -

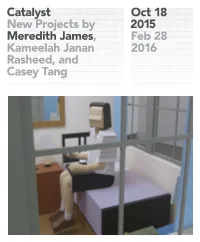

Catalyst New Projects by Meredith James, Kameelah Janan Rasheed

Catalyst Oct 18 New Projects by 20 15 Meredith James, Feb 28 Kameelah Janan 2016 Rasheed, and Casey Tang Meredith James is interested in perception—the way we see our immediate Catalyst environment and ourselves inside it. Perception can work in ways that are Oct 18 habitual or biased, predefined or unpredictable. Working in video, sculpture, and theater, James experiments with the physical and optical anatomy of New Projects by space, where perspective can be manipulated and observation influenced. 20 15 James’ new project, Mobius City, 2015, is inspired by the Museum’s Meredith James, Panorama of the City of New York, the gigantic miniature with nearly 900,000 individual structures rendered at a scale of 1:1,200. Originally Feb 28 Kameelah Janan commissioned for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the model may be a static, old-fashioned way of representing space, but it is unsurpassed in its ability to show an urban environment as a three-dimensional totality. James Rasheed, and found her East Village apartment building on the Panorama, imagined her 2016 apartment in it, and pictured herself inside of it—like we all do! Mobius City Casey Tang is a fantastical daydream in the form of sculptural installation with video, staged in and structured around three real spaces: the artist’s apartment in a 12-story building on 4th Avenue and 12th Street; its double as a near-life- size sculpture; and, the tiny model of the apartment building, standing two inches tall on the Panorama. Cover: Still from Meredith James, Mobius Made of wood and painstakingly painted, the apartment replica in the City, 2015, mixed media installation; video, 7’ gallery is designed in the simplified style of the miniature buildings on the 35”, no sound, looped.