Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kv2 Dysfunction After Peripheral Axotomy Enhances Sensory Neuron

Our reference: YEXNR 11584 P-authorquery-v11 AUTHOR QUERY FORM Journal: YEXNR Please e-mail or fax your responses and any corrections to: Bennett, Timothy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 619 699 6721 Article Number: 11584 Dear Author, Please check your proof carefully and mark all corrections at the appropriate place in the proof (e.g., by using on-screen annotation in the PDF file) or compile them in a separate list. Note: if you opt to annotate the file with software other than Adobe Reader then please also highlight the appropriate place in the PDF file. To ensure fast publication of your paper please return your corrections within 48 hours. For correction or revision of any artwork, please consult http://www.elsevier.com/artworkinstructions. Any queries or remarks that have arisen during the processing of your manuscript are listed below and highlighted by flags in the proof. Click on the ‘Q’ link to go to the location in the proof. Location in article Query / Remark: click on the Q link to go Please insert your reply or correction at the corresponding line in the proof Q1 Please confirm that given names and surnames have been identified correctly. Q2 Please check the layout of Table 5, and correct if necessary. Q3 A dummy footnote citation of footnote [**] has been inserted as a corresponding footnote text has been provided. Please check if the placement is correct and amend if necessary. Q4, Q5 This sentence has been slightly modified for clarity. Please check that the meaning is still correct, and amend if necessary. -

2012: Providence, Rhode Island

The 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt April 27-29, 2012 Renaissance Providence Hotel Providence, RI Photo Credits Front cover: Egyptian, Late Period, Saite, Dynasty 26 (ca. 664-525 BCE) Ritual rattle Glassy faience; h. 7 1/8 in Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund 1995.050 Museum of Art Rhode Island School of Design, Providence Photography by Erik Gould, courtesy of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Photo spread pages 6-7: Conservation of Euergates Gate Photo: Owen Murray Photo page 13: The late Luigi De Cesaris conserving paintings at the Red Monastery in 2011. Luigi dedicated himself with enormous energy to the suc- cess of ARCE’s work in cultural heritage preservation. He died in Sohag on December 19, 2011. With his death, Egypt has lost a highly skilled conservator and ARCE a committed colleague as well as a devoted friend. Photo: Elizabeth Bolman Abstracts title page 14: Detail of relief on Euergates Gate at Karnak Photo: Owen Murray Some of the images used in this year’s Annual Meeting Program Booklet are taken from ARCE conservation projects in Egypt which are funded by grants from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The Chronique d’Égypte has been published annually every year since 1925 by the Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth. It was originally a newsletter but rapidly became an international scientific journal. In addition to articles on various aspects of Egyptology, papyrology and coptology (philology, history, archaeology and history of art), it also contains critical reviews of recently published books. -

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

The Work of the Theban Mapping Project by Kent Weeks Saturday, January 30, 2021

Virtual Lecture Transcript: Does the Past Have a Future? The Work of the Theban Mapping Project By Kent Weeks Saturday, January 30, 2021 David A. Anderson: Well, hello, everyone, and welcome to the third of our January public lecture series. I'm Dr. David Anderson, the vice president of the board of governors of ARCE, and I want to welcome you to a very special lecture today with Dr. Kent Weeks titled, Does the Past Have a Future: The Work of the Theban Mapping Project. This lecture is celebrating the work of the Theban Mapping Project as well as the launch of the new Theban Mapping Project website, www.thebanmappingproject.com. Before we introduce Dr. Weeks, for those of you who are new to ARCE, we are a private nonprofit organization whose mission is to support the research on all aspects of Egyptian history and culture, foster a broader knowledge about Egypt among the general public and to support American- Egyptian cultural ties. As a nonprofit, we rely on ARCE members to support our work, so I want to first give a special welcome to our ARCE members who are joining us today. If you are not already a member and are interested in becoming one, I invite you to visit our website arce.org and join online to learn more about the organization and the important work that all of our members are doing. We provide a suite of benefits to our members including private members-only lecture series. Our next members-only lecture is on February 6th at 1 p.m. -

La Tumba-Cenotafio Del Visir Rej-Mi-Re

Revista Anahgramas. Número V. Año 2018. Esteve Pérez. Pp315-401. LA TUMBA-CENOTAFIO DEL VISIR REJ-MI-RE: ANÁLISIS CONTEXTUAL E ICONOGRÁFICO Marina Esteve Pérez1 Email: [email protected] Resumen: Rej-mi-Re fue gobernador de la ciudad y visir del Alto Egipto en una de las épocas más florecientes del Antiguo Egipto, la Dinastía XVIII, durante el reinado de Tutmosis III en la ciudad de Tebas. El testimonio tangible del poder que adquirió un visir es la TT100, su morada de eternidad, la cual nunca pudo ser utilizada por la temprana desaparición del Gobernador Rej-mi-Re. Palabras clave: Rej-mi-Re, visir, Dinastía XVIII, Tebas, TT100. THE TOMB-CENOTAPH OF THE VIZIER REKHMIRE: CONTEXTUAL AND ICONOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS Abstract: Rekhmire was governor of the city and vizier of Upper Egypt in one of the most flourishing periods of Ancient Egypt, XVIII Dynasty, during the reign of Thutmose III in the city of Thebes. The tangible testimony of the power acquired by a Vizier is the TT100, his abode of eternity, which was never used due to the early disappearance of Governor Rekhmire. Key words: Rekhmire, Vizier, XVIII Dynasty, Thebes, TT100. 1 Doctorando en Patrimonio de la Universidad de Córdoba, departamento de Historia del Arte, Arqueología y Música. 315 Revista Anahgramas. Número V. Año 2018. Esteve Pérez. Pp315-401. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN La Dinastía XVIII es, sin ninguna duda, una de las épocas más florecientes del Antiguo Egipto. Es sencillo, cuando te acercas al estudio del Antiguo Egipto, sucumbir al encanto de las Pirámides de Guiza, el Valle de los Reyes o los grandes espeos de Abu Simbel. -

20120723 Newsletter 119.Indd

uly 2012 R F E A The Rundle Foundation J for Egyptian Archaeology Issue 119 AUSTRALIA Newsletter THE DECORATION PROGRAM OF TT233, THE TOMB OF SAROY AND AMENHOTEP: A REFLECTION OF THEIR OWNERS’ INTERESTS? FIG. 1. BROAD HALL, WEST WALL SOUTH, MIDDLE REGISTER: SAROY AND AMENHOTEP BEFORE OSIRIS WITH ROYAL RITUAL TEXT The decoration program of a New Kingdom tomb often refl ects West wall BD 18 deals with the ten tribunals before which the its owner’s occupation. In the tomb of Pahery, mayor of Elkab, deceased has to appear. Thoth is asked to aid Saroy so that he can we see the collection of gold and its transport to the residence. be justifi ed as Osiris was justifi ed in the myth. The tomb of the vizier Rekhmire (TT100) includes texts relevant BD Chapter 130 also appears on the West wall. Its theme is to the vizier (“Installation” and “Instructions”) as well as the freedom of movement, as the opening words indicate: “The depiction of a court session, the collection of taxes in Egypt heavens have been opened, the earth has been opened, the west and the reception of foreigners with their produce, all activities has been opened, the east has been opened, the southern shrine in which the vizier was involved. This also holds true for the has been opened, the northern shrine has been opened, the doors Ramesside period, when it is often said that scenes of everyday and the gates have been opened for Re, that he might emerge life give way to religious themes. -

Protective Zika Vaccines Engineered to Eliminate Enhancement of Dengue Infection Via Immunodominance Switch

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-00966-6 Protective Zika vaccines engineered to eliminate enhancement of dengue infection via immunodominance switch Lianpan Dai 1,2,3,8 ✉ , Kun Xu3,8, Jinhe Li2,4,8, Qingrui Huang5, Jian Song 1, Yuxuan Han2, Tianyi Zheng2,4, Ping Gao2,4, Xuancheng Lu6, Huabing Yang 5, Kefang Liu7, Qianfeng Xia3, Qihui Wang 1, Yan Chai1, Jianxun Qi 1, Jinghua Yan 5 ✉ and George F. Gao 1,2,4 ✉ Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) is an important safety concern for vaccine development against dengue virus (DENV) and its antigenically related Zika virus (ZIKV) because vaccine may prime deleterious antibodies to enhance natural infections. Cross-reactive antibodies targeting the conserved fusion loop epitope (FLE) are known as the main sources of ADE. We design ZIKV immunogens engineered to change the FLE conformation but preserve neutralizing epitopes. Single vaccination conferred sterilizing immunity against ZIKV without ADE of DENV-serotype 1–4 infections and abrogated maternal–neonatal transmis- sion in mice. Unlike the wild-type-based vaccine inducing predominately cross-reactive ADE-prone antibodies, B cell profiling revealed that the engineered vaccines switched immunodominance to dispersed patterns without DENV enhancement. The crystal structure of the engineered immunogen showed the dimeric conformation of the envelope protein with FLE disruption. We provide vaccine candidates that will prevent both ZIKV infection and infection-/vaccination-induced DENV ADE. IKV is a mosquito-borne pathogen belonging to the genus models12,13,19,20. More importantly, a recent study of pediatric cohorts Flavivirus in the family Flaviviridae1. The 2015–2016 ZIKV in Nicaragua clearly shows that previous ZIKV infection enhanced epidemic spread to 84 countries worldwide, including future risk of DENV2 disease and severity, as well as DENV3 sever- Z2,3 21,22 China . -

The Shrines of Gebel El-Silsila and Their Function

Department of Archaeology and Ancient History The Shrines of Gebel el-Silsila and their function Alexandra Boender BA Thesis, 15 ECTS in Egyptology Spring 2018 Supervisor: Sami Uljas Boender, A. 2018, The Shrines of Gebel el-Silsila Boender, A. 2018, Helgedomarna i Gebel el-Silsila ABSTRACT In 1963 came Ricardo Caminos to the conclusion that the shrines of Gebel el-Silsila functioned as cenotaphs. However, his views have never been reassessed by contemporary Egyptologists, which has led to the shrines still being interpreted as cenotaphs today. This study shows that the term cenotaph perhaps is not the correct word to use for their function. The focal point of this study are the decorations and inscriptions of the shrines, their religious character and the importance of the Nile. The following research compares the shrines of Gebel el-Silsila with similar shrines at Qasr Ibrim in order to reveal their similarities and dissimilarities. In order to achieve this, two publications were chosen, by Caminos, who assessed both sites in the 1960s and briefly compares the Qasr Ibrim shrines to Gebel el-Silsila. Furthermore, the shrines of Gebel el-Silsila resemble tombs in the Theban necropolis, where some of the tombs of the shrine-owners have been uncovered. For this reason, a comparison between the shrines and tombs has been made in order to reveal why the shrines cannot be tombs, and to display why the shrines still are mortuary monuments. Lastly, the following study assessed the shrine- owners in order to answer how the shrines were financed. However, although many of the shrine-owners are well-established noblemen of which several accounts are known, only their titles are taken into account for they provide a principal overview of their status. -

Subunits Identified in the Human Genome

Obligatory heterotetramerization of three previously uncharacterized Kv channel ␣-subunits identified in the human genome N. Ottschytsch, A. Raes, D. Van Hoorick, and D. J. Snyders* Laboratory for Molecular Biophysics, Physiology, and Pharmacology, University of Antwerp (UIA) and Flanders Institute for Biotechnology (VIB), B2610 Antwerp, Belgium Edited by Lily Y. Jan, University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA, and approved April 12, 2002 (received for review November 20, 2001) Voltage-gated K؉ channels control excitability in neuronal and sense, these ‘‘silent’’ subunits can be considered regulatory various other tissues. We identified three unique ␣-subunits of subunits—e.g., the metabolic regulation of the Kv2.1͞Kv9.3 -voltage-gated K؉-channels in the human genome. Analysis of the heteromultimer might play an important role in hypoxic pulmo full-length sequences indicated that one represents a previously nary artery vasoconstriction and in the possible development of uncharacterized member of the Kv6 subfamily, Kv6.3, whereas the pulmonary hypertension (8). others are the first members of two unique subfamilies, Kv10.1 and In this study we report the cloning and functional properties Kv11.1. Although they have all of the hallmarks of voltage-gated of three previously uncharacterized subunits that were identified K؉ channel subunits, they did not produce K؉ currents when in the early public draft version of the human genome. Based on expressed in mammalian cells. Confocal microscopy showed that sequence identity, one of these is a previously uncharacterized Kv6.3, Kv10.1, and Kv11.1 alone did not reach the plasma mem- member of the Kv6 subfamily (Kv6.3), whereas the others are the brane, but were retained in the endoplasmic reticulum. -

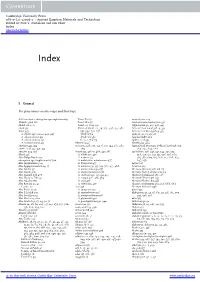

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

Occupational Safety and Health Among Brick Workers in the Old Testament (Pentateuch)

Mazokopakis EE. Occupational Safety and Health among Brick Workers in the Old Testament (Pentateuch). Annals of Global Health. 2019; 85(1): 65, 1–2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2493 LETTER TO THE EDITOR Occupational Safety and Health among Brick Workers in the Old Testament (Pentateuch) Elias E. Mazokopakis*,† Dear Editor, I read with great interest the article by Rupakheti et al. [1] about the occupational safety and health vulner- ability among brick factory workers in Dhading District, Nepal. However, a story of occupational safety and health among brick workers has been described in the Bible and particularly in the Book of Exodus, the second book of the Pentateuch or Torah, and occurred probably dur- ing the 13th century BC. It is known that the Egyptians oppressed the Israelites in Egypt with the hard labor of Figure 1: Slaves (probably Israelites) manufacture and brick construction. According to the biblical text, when transport bricks in Egypt. Mural from the private tomb a new pharaoh (18th or 19th Egyptian Dynasty; probably (Theban Tomb 100; TT100) of vizier (during the reigns of Ramses II; reign: 1279–1213 BC, 19th Egyptian Dynasty), Thutmosis III and Amenhotep II, 18th Egyptian Dynasty) who did not know Joseph, came to power in Egypt, fearing Rekhmire on the West Bank at Luxor (ancient Thebes). that the Israelites might join their enemies, fight against At the left, water is being town to moisten the clay. Next Egyptians, and depart from the land, he “appointed task- clay is kneaded and then (center) carried to two men masters over them to afflict them with hard labor. -

Integration of Foreigners in Egypt the Relief of Amenhotep II Shooting Arrows at a Copper Ingot and Related Scenes

Journal of Egyptian History �0 (�0�7) �09–��3 brill.com/jeh Integration of Foreigners in Egypt The Relief of Amenhotep II Shooting Arrows at a Copper Ingot and Related Scenes Javier Giménez Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya (Barcelona-Tech) [email protected] Abstract The relief of Amenhotep II shooting arrows at a copper ingot target has often been considered as propaganda of the king’s extraordinary strength and vigour. However, this work proposes that the scene took on additional layers of significance and had different ritual functions such as regenerating the health of the king, and ensuring the eternal victory of Egypt over foreign enemies and the victory of order over chaos. Amenhotep II was shooting arrows at an “Asiatic” ox-hide ingot because the ingot would symbolize the northern enemies of Egypt. The scene belonged to a group of representations carved during the New Kingdom on temples that showed the general image of the king defeating enemies. Moreover, it was linked to scenes painted in pri- vate tombs where goods were brought to the deceased, and to offering scenes carved on the walls of Theban temples. The full sequence of scenes would describe, and ritual- ly promote, the process of integration of the foreign element into the Egyptian sphere. Keywords Amenhotep II stela – ox-hide ingot – offering scenes – scenes of goods brought to the deceased * I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments which led me to consider an additional meaning of the scene in Min’s tomb (TT109) and the possibility that the Egyptians regarded the ox-hide ingot as a marvel from a land beyond Egypt’s sphere of control.